Half-Year Investor Letter – July 2025

Written for the most important investors I manage money for: my parents.

Let’s kick things off with a brief update before we dive into the more fundamental ideas. The portfolio has performed steadily during the first few months of its existence, with solid gains across several core holdings (especially Meta and IBKR), a few smaller positions that have started to show promise, and a few companies that are down in price since we bought them (e.g. Brockhaus Technology). While no major breakouts have occurred just yet, I’m not chasing fireworks – I’m building a portfolio of durable businesses that can compound quietly over time. We’ll discuss some noteworthy developments and the newly added positions further down below.

In these letters, I want to go beyond performance commentary and use the opportunity to introduce one or two core investing concepts each time. Think of it as a slow, deliberate process of building a shared framework – something that helps make sense of what we’re doing, why we’re doing it this way, and how I believe this approach can lead to long-term outperformance.

In the last letter, I laid the foundation by explaining our investment philosophy: only invest in businesses we truly understand, ideally run by founders or exceptional operators, protected by structural advantages that lead to sustainably high returns on capital. These companies must also have strong balance sheets – and crucially, we only buy them when they’re available at a meaningful discount to what they’re worth. That’s our recipe.

But knowing what to look for is only one part of the puzzle. There are really just three levers that drive long-term investment returns:

(1) Security selection – the process of identifying great businesses at attractive prices, using the framework above;

(2) Position sizing – how much capital to allocate to each investment; and

(3) Market timing – or better said, the ability to exploit behavioral inefficiencies at the right moments, when the wisdom of the crowd gives way to the madness of the crowd.

This time, I want to zoom in on the second lever: position sizing.

Why Position Sizing Makes or Breaks a Portfolio

Most investors spend nearly all their energy on security selection – and almost none thinking about position sizing. But in reality, how much you invest in a particular idea often matters more than whether the idea is right.

Here’s a simple illustration. Say we invest in two stocks: one is a 10% position that rises 10%, the other is a 1% position that doubles. Despite the 100% return on the smaller bet, both investments generate the same dollar return. So what’s the takeaway? When you find something you truly believe in, you need to let it count.

A blog post I came across recently sharpened this point further. It described two fictional portfolios:

Portfolio A owns ten stocks, eight of which are small 6.25% positions that all double. The remaining two are large 25% bets that each lose half their value.

Portfolio B also holds ten names. Nine of them are tiny and each loses 50%. But the final one – a bold 43.75% position – triples.

On the surface, the investor behind Portfolio A looks like a genius, hitting 8 out of 10. The Portfolio B investor looks like an amateur with a 90% failure rate.

But the outcomes tell a different story. Portfolio A returns 25%. Portfolio B? It ends up with a 37.5% gain.

John Burbank once said: "I want to have sizeable positions because if you're right that's how you can do really well, but I know if it's not expected by the market the path isn't linear, so you just have to understand how much you can tolerate." That’s the essence of effective sizing. You don’t get paid for being right often – you get paid for being right big.

Some Lessons I’m Taking to Heart

From everything I’ve read and studied on this topic lately, a few key ideas have stuck with me.

First, I don’t want to size positions based on potential upside. I want to size them based on downside risk. The goal isn’t to bet the farm on moonshots – it’s to scale up the safest, most resilient ideas. The ones with multiple paths to success and few ways to lose permanently.

“We will make something a large position if we think there is an extremely low chance of losing money on a permanent basis. Even if we think it might be a 4X return, if the idea could be a zero, it’ll be a small position.” Ken Shubin Stein

Second, hit rate doesn’t matter if your sizing is off. You can be right most of the time and still underperform if your largest positions are your worst ones. And vice versa – you can be wrong often and still outperform if your rare winners are given enough room to shine.

Third, concentration itself isn’t dangerous. What you concentrate on is what matters. There’s a world of difference between putting 20% into a speculative biotech stock and putting 20% into a cash-generating market leader with 15 years of reinvestment runway. That’s where edge lies.

But none of this means you should size recklessly. I always want to leave room to be wrong. Position sizing is not just about maximizing returns – it’s about staying in the game. And staying in the game means never letting one loss take you out of it.

Fewer Stocks, More Volatility – But Also More Clarity

Closely linked to the topic of sizing is the question of how many stocks to own in total. In broad terms, the fewer positions you hold, the more your portfolio will swing – up or down – based on the fortunes of just a few companies. That’s the price of focus. But if you want your winners to count, you need to let them breathe. Owning 40 stocks, each weighted at 2.5%, means even a 3x return barely moves the needle.

But there’s a tradeoff here. Fewer positions means greater volatility – and the emotional burden that comes with it. That burden isn’t for everyone. Personally, I believe the sweet spot for most thoughtful investors is somewhere between 5 and 20 holdings. Once you reach the higher end of that spectrum, the benefits of diversification begin to flatten. You’ve lowered the portfolio’s volatility enough to avoid disaster from one bad call – but not so much that your winners get diluted to irrelevance. And the incremental benefits of adding another position diminish.

That said, for your portfolio, I’m deliberately leaning closer to the higher end of that range. You’re still fairly new to investing, and I want to smooth the ride somewhat. Volatility is only your friend once you truly understand the underlying businesses – and are confident in how they’ll behave over time. Until then, I believe it’s wise to trade a bit of upside potential for peace of mind.

Capital Deployment: Progress, Patience, and the Hurdle Rate Mindset

When we first began this journey together, we were sitting on 100% cash. Since then, the portfolio has taken shape slowly – and deliberately. We’re now 66% invested, with 34% still in cash. In other words, we’ve made steady progress, but we haven’t rushed.

That’s by design. At any given time, there simply aren’t 15 exceptional opportunities just lying around – at least not for an individual investor who insists on understanding each business deeply. The process of allocating capital is inherently lumpy. Real opportunities tend to come in clusters. And when they do, they tend to be obvious – not in the sense that everyone sees them, but in the sense that you see them clearly after doing the work.

There’s a useful mental model here around hurdle rates that’s helped guide my thinking. Imagine you’re still sitting on a full cash pile. In that situation, the drag on returns from holding cash is enormous – so your bar for making the first investment should be relatively low. Even a decent idea is better than zero return (or a guaranteed negative real return once you account for inflation). But as that cash pile shrinks, the bar should rise. The marginal dollar becomes more precious. You’re no longer looking for good ideas – you’re looking for truly great ones that can compete with the portfolio you’ve already assembled and that can move the needle.

So, if the hurdle rate for the first 10% of capital might only be 10%, then by the time you’re down to your last 10% of deployable cash, the hurdle rate might be closer to 15–20%. It’s a spectrum, not a fixed threshold.

When we wrote the inaugural letter, we had initiated five positions – LVMH, Interactive Brokers, Wise, Meta Platforms, and Evolution Gaming – and had begun building a position in Computer Modelling Group. Cash was still the portfolio’s largest “holding,” and it still is. But our exposure has meaningfully increased since then, and with it, the breadth and depth of the businesses we now own.

Before I walk through the new holdings, I want to reiterate something important: this is not a collection of ticker symbols. These are businesses. You’re a part owner of each of them. If you haven't already, or it’s been a while, I’d encourage you to go back to the first letter and revisit the reasoning behind the original positions. Understand what each business does, how it makes money, and who runs it. That understanding is what allows you to hold through volatility with confidence. It’s also what makes the process of investing fun – you are an actual owner, an owner of some of the best businesses in the world.

Now let’s turn to the newest additions to the portfolio.

Ashtead Technology: Riding the Subsea Infrastructure Boom (9.1% of the Portfolio)

Ashtead Technology is a specialist provider of subsea equipment and services used in the offshore energy sector. The company serves a mix of oil & gas operators and – increasingly – offshore wind developers. While not a household name, Ashtead plays a critical role in the inspection, maintenance, and repair, and decommission of subsea infrastructure. It rents out highly technical equipment like remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), sensors, and positioning tools, and complements these rentals with expert services.

What drew me to Ashtead is the combination of capital-light business economics (at least more capital light than the business description would make you think), mission-critical solutions, and a secular tailwind: the global build-out of offshore infrastructure and the tendency of Ashtead customers to own less equipment themselves. The management team has also proven itself adept at bolt-on acquisitions that expand Ashtead’s footprint and capabilities without overstretching the balance sheet. Their returns on capital are excellent, and while this business operates in a niche, the niche is growing – and barriers to entry are real – and getting stronger as Ashtead becomes the one-stop shop for subsea rental equipment. Ashtead meets our framework criteria on structural advantages, attractive reinvestment opportunities, and conservative capital allocation.

Feel free to read the deep dive we shared on the blog:

More recently, after reporting half-year results that showed strong topline growth driven by two recent acquisitions (but organic revenue decline), the stock dropped by more than 20%. We believe the market is wrong about the long-term outlook of the business, and explained our reasoning also on the blog:

Brockhaus Technologies: A Higher-Risk Bet on German Hidden Champions (4.2% of the Portfolio)

Brockhaus Technologies is a technology holding company listed in Germany. It acquires and grows what it calls “hidden champions” – small, founder-led, high-margin businesses in areas like high-security communications, optical measurement systems, and mobility.

What attracted me here is the quality of the underlying portfolio – which at this point only consists of two companies (Bikeleasing.com and IHSE) –, the operating leverage embedded in the bikeleasing business model, and the fact that the company is still relatively underfollowed.

That said, Brockhaus comes with more risk than our average holding. The accounting irregularities at one subsidiary (IHSE) earlier this year shook investor confidence, and while I believe the issue is contained, it’s something I’m watching closely. I’ve sized the position accordingly – it's smaller, reflecting both the opportunity and the risk. But if Brockhaus executes on its strategy of disciplined M&A and operational improvement, the upside is meaningful.

Today, Brockhaus is primarily a bet on Bikeleasing.de, which has become the centerpiece of the portfolio following the underperformance and impairment of IHSE. Bikeleasing is a platform that enables employees to lease e-bikes and traditional bikes through their employer, using a salary-sacrifice model similar to company car schemes. For employees, this often means 30–40% savings on a high-quality bike. For employers, it's an attractive fringe benefit that costs little but signals modernity and health-consciousness. Bikeleasing takes a cut from financing partners, insurance providers, and service agreements – generating revenue the moment a bike is delivered.

It’s a compelling model, but it’s also facing growing headwinds. The COVID-era bike boom created a massive one-time boost, both in consumer demand and in companies rushing to offer cycling perks to attract talent in a tight labor market. But that tailwind is gone. We’re now moving back to more of an “employer’s market,” and most of the low-hanging fruit – companies new to the idea – have already adopted it. Bikeleasing’s impressive customer growth is harder to replicate going forward, and the company has to rely more heavily on repeat business from existing clients going forward. Meanwhile, it shifted its pricing model in a way that supports margin stability but limits growth – by introducing a variable leasing factor, it effectively excluded a portion of price-sensitive users, reducing total volume.

There’s also a second-order dynamic at play: the bike return cycle. Leasing contracts are usually 3 years long, after which the bikes are returned and resold by Bikeleasing. We’re now in the phase where large volumes of bikes are coming back, generating revenue from resale but little to no margin as it’s a low-margin business. This secondary market activity ties up capital and demands new operational infrastructure – warehousing, refurbishment, resale channels – under the Bike2Future brand and thus compresses profitability. This “return wave” will likely persist for at least two more years before stabilizing.

The idea behind Brockhaus was to use debt-fueled acquisitions to build a diversified portfolio of cash-generative niche players. But for that model to work, the holding company must actually acquire new businesses. And that’s where the criticism begins. Since Bikeleasing, Brockhaus has been mostly inactive. The longer this acquisition drought continues, the more obvious the cost of the holding structure becomes. Investors are now shouldering the overhead of a listed vehicle – a bloated corporate layer – without seeing the scale benefits that should justify it. Operating expenses for the AG structure are estimated at around €6 million annually, a number that looms large when there’s no M&A activity to absorb it and relatively little cash profit to please shareholders.

There’s also the issue of financial engineering and transparency. Brockhaus has a tendency to present adjusted metrics that put the business in the best possible light, while the consolidated financials tell a more sober story. This has been the case for years, but it’s become harder to overlook now that organic growth is slowing and bolt-on acquisitions are absent. The company’s structure – with the CEO and a few anchor shareholders effectively controlling the supervisory board – also raises governance concerns, especially around incentives and accountability.

IHSE adds its own set of complications. Originally sold by Brockhaus Private Equity to the listed AG, the purchase price looks rich with the benefit of hindsight. COVID clearly derailed the original growth story. Competitors caught up, the U.S. now slapped 15% tariffs on IHSE’s core products, and much of the goodwill has now been written off – reflecting permanently lower earnings expectations. A sale of IHSE is a possible future scenario, especially now that the business has been fully impaired and operationally “cleaned up.” If a strategic buyer emerges, a sale could probably yield at least €50 million or more – potentially freeing up capital for a much-needed fresh acquisition.

Given all this, why stay invested?

Because even in a muddled structure, there can still be pockets of value. If Bikeleasing alone can generate €40–50 million in annual cash flow post-deleveraging, and IHSE is sold for a fair price, then the intrinsic value of the parts could well exceed the current market cap. That’s the crux of the sum-of-the-parts thesis. But make no mistake – execution risk is high, and patience is required. This is not a wide-moat compounder. It’s more of a special situation investment, sized accordingly (4% as of the time of writing).

I’ve recently published an open letter to the CEO of Brockhaus Technologies. It outlines my concerns and offers suggestions for course correction. Whether it will be read or considered is another matter. But shareholder pressure has to start somewhere.

Zalaris: Building a Scalable Platform in HR Outsourcing (6.2% of the Portfolio)

Zalaris is a Norwegian-based provider of outsourced payroll and HR services, primarily targeting large companies across the Nordics and the DACH region. Their platform helps large enterprises (usually with thousands of employees) manage employee data, payroll compliance, and HR analytics at scale. It’s a sticky, recurring-revenue business with long-term contracts (5 years on average) and deep integrations into clients’ internal systems.

Again, I shared an in-depth analysis of the company on the blog (as you can tell, there are a lot of (optional) reading assignments). I will link it below. In the post I shared a “90 second pitch.” I’ll share it again here:

“Zalaris is flying under the radar. It’s a niche European payroll and HR outsourcing provider, trading at a modest valuation while quietly compounding revenue, margins, and free cash flow. Over the last 2.5 years, the stock is up around 180% – and it’s still only beginning to rerate.

So why should you care now?

Because Zalaris is transitioning from a steady operator into a potential category leader in multi-country payroll. Organic revenue growth is solid. Margins are expanding. The stock is still barely followed (I couldn’t find a single write-up on the name except a 2015 VIC analysis). And following a recently concluded strategic review, the company made a deliberate decision not to sell – because management believes it’s worth much more if left to compound.

My thesis is simple: the market is underestimating the operating leverage, moat durability, and multi-year growth runway of Zalaris’s model. It’s treating this like a sleepy BPO business in a low-growth region. But what’s really happening is a quiet transformation into a leaner, more tech-enabled payroll platform with secular tailwinds, high switching costs, and a proven land-and-expand strategy.

“… with a more clearly defined land and expand strategy aimed at scaling both within existing accounts and across new geographies. We believe growth will be fueled by a combination of upselling new services to existing clients expanding geographic reach with the goal of establishing operations in all G20 countries and full market coverage in Western Europe as the first step and maximizing utilization of our existing capacity and infrastructure to operator incremental margins.“ Q1 2025 Call

Here’s the pitch:

Sticky, mission-critical product – Zalaris runs payroll solutions for over 340,000 employees at blue-chip firms across Europe and serves 1.5 million employees with any of their HR solutions. It’s embedded in its clients’ operations and isn’t easily replaced. Long-term contracts (5 years on average) and compliance complexity drive high switching costs.

Founder-led, aligned, and executing – CEO Hans-Petter Mellerud still runs the business after 25 years and owns ~13%. He’s balancing profitable growth with prudent capital allocation and margin expansion.

Revenue accelerating, margins inflecting – FY2024 revenue grew 19%, with EBIT margins at 8.5%. Q1 2025 continued the trend: 16% growth and a 11.3% margin (14.1% adj. EBIT margins). Management is now guiding for NOK 2 billion in revenue by 2028 with 13–15% EBIT margins.

Secular tailwinds + underpenetrated market – Payroll outsourcing, cloud transitions, and growing compliance burdens all play into Zalaris’s hands. Most large firms still manage payroll in-house or use patchwork solutions. That’s changing.

Mispriced optionality and rerating potential – Even after the recent run, Zalaris trades far below its intrinsic value (9.5x EBIT) given the cash flow potential, predictability, and scarcity value of a scaled, independent European payroll platform.

This isn’t a moonshot. It’s a predictable, sticky business that can double earnings power in the next 4–5 years and still be growing. The upside case doesn’t require heroic assumptions – just continued execution and a broader market realization that this is no longer a sleepy Nordic services firm.

Edenred: From Meal Vouchers to a Global Transaction Network (6.4% of the Portfolio)

Edenred started life as a paper-based meal voucher business in France. Today, it operates a global digital payments and benefits platform that serves employers, employees, and merchants. Through prepaid cards, apps, and software systems, Edenred connects millions of users across multiple verticals: employee benefits, fleet and mobility, and corporate payments. Think of it as an “infrastructure layer” for highly specific, high-frequency transactions that need to be tightly controlled and audited.

What’s compelling about Edenred is how it monetizes multiple sides of the network: it charges fees to employers, to merchants, and makes money on the float (i.e. it earns interest on funds kept at Edenred during the time between when funds are loaded and when they’re spent). It’s a beautiful business model – capital-light, recurring, and highly scalable. The business meets our key criteria on almost every front: structural moat, high returns on capital, healthy balance sheet, and a clear growth runway.

However, the last few months (and years) have been more turbulent if you only consider the share price performance. The last year in particular brought turbulence. The French government signaled possible regulatory reforms to the country’s meal voucher system – Edenred’s historical core and still a significant contributor to its bottom line. The initial proposals – particularly talk of capping merchant fees – raised concerns over profitability, prompting a sharp selloff in the stock.

That narrative shifted meaningfully in late June. On June 25, French Minister Delegate Véronique Louwagie unveiled the revised policy direction: the government ruled out any cap on merchant fees, at least for now, and instead opted for a transparency charter to guide the relationship between voucher issuers and merchants. Additional reforms include the full transition to digital vouchers by February 2027 (something Edenred is more than ready for), expanding redemption options (permanent supermarket eligibility, Sunday use), and streamlining oversight by transferring regulatory authority from the National Commission to the Banque de France. One slightly negative tweak: unused voucher balances will no longer roll over, though the €25 daily cap will remain. All in, this package is far less punitive than feared – and may even reinforce Edenred’s competitive edge as a digital-first operator.

That said, France isn’t the only jurisdiction under scrutiny. Brazil – another important market for Edenred – is currently mulling reforms that could prove more disruptive. Reports suggest the government is considering a 3.5% cap on merchant rates for meal vouchers, significantly below industry norms.

Still, in the bigger picture, I believe the Edenred thesis remains intact. The regulatory noise, while uncomfortable, is unlikely to undermine the core value proposition of a business that benefits from network effects, switching costs, and rising digital penetration. If anything, these recent developments highlight why vigilance around business models dependent on government frameworks is essential – and why staying close to the facts, rather than market sentiment, remains a key edge for long-term investors.

A Quick Word on the Existing Holdings

Let me briefly touch on the businesses we already discussed in the inaugural letter. LVMH continues to report declining revenues, particularly in fashion and leather goods, as the post-COVID boom normalizes and aspirational consumers pull back. I believe this reveals a truth many ignored during the luxury bull run: the sector is more cyclical than its brand sheen implies. That said, LVMH still owns the most enviable brand portfolio in global luxury in terms of broad diversification, and with long-term pricing power (i.e. increasing prices above the rate of inflation, which by the way, I think may trend upward again in the coming months), modest volume growth, and the kind of balance sheet that allows opportunistic acquisitions when others retrench, we believe the business will ultimately get back on the long-term growth trendline of around 10% annually. Interactive Brokers keeps doing what it does best – onboarding new customers at 20–30% annual rates, expanding its product suite, and benefiting from global account migration toward low-cost, high-functionality platforms. Similarly, Wise continues to gain traction, not just with consumers but increasingly with institutions. The most recent highlight: a major deal with UniCredit, making it the first large European bank to fully integrate Wise’s cross-border payments infrastructure for its retail clients.

Meta Platforms will report earnings later today. I actually exited the position in my personal account, where I’m more aggressive, aim for a slightly higher return, and am willing to accept steep volatility in exchange for these higher expected returns. But for your portfolio, Meta remains a foundational holding – a cash-generating machine led by a founder who understands the magnitude of the AI transition and is willing to play offense. I expect future expected returns to be broadly in line with Meta’s long-term earnings growth (hopefully in the low- to mid-teens range). Evolution Gaming, meanwhile, is quietly shifting its revenue mix, reducing gray market exposure and growing its regulated footprint – a necessary and value-preserving move in the long run. Finally, Computer Modelling Group is set to report earnings in early August. The core business remains solid, and we continue to hope that another, hopefully smart, acquisition under the “CMG 4.0” playbook will be announced in the near future.

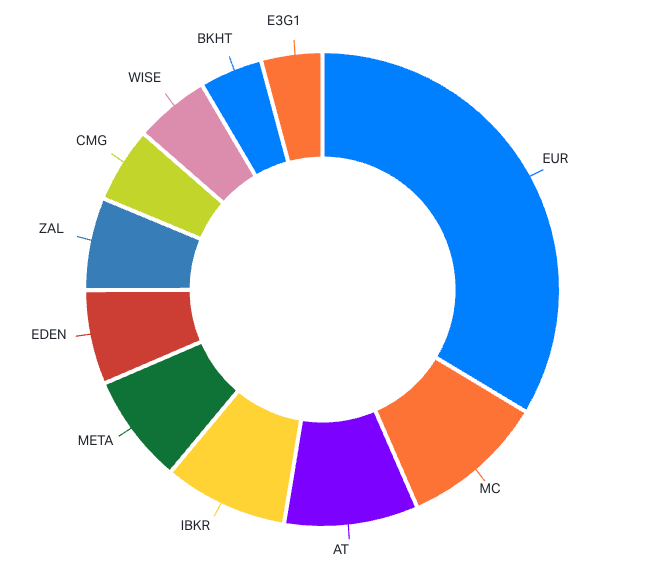

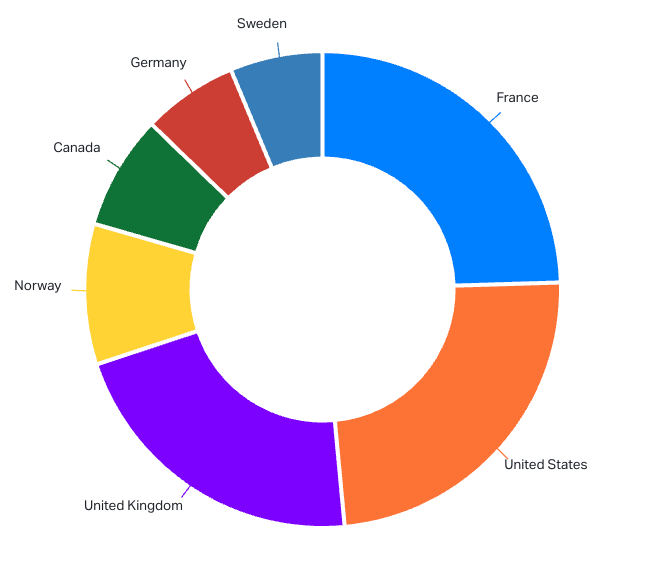

Here’s an overview of the current portfolio (in terms of position size and geographic exposure):

Looking Ahead

As we move into the second half of the year, I remain fully committed to the framework we set out from the beginning: own a small number of understandable, resilient businesses led by capable people and bought at attractive prices. But execution is never linear. Some quarters will feel quiet, others frustrating. Sometimes we’ll be patient because the market isn’t offering much. Other times we’ll move quickly because opportunities are obvious. That’s the nature of this game – one of controlled pacing, not constant action.

I also want to take a moment to acknowledge something important: you're doing a great job not checking prices obsessively – as far as I can tell, not checking prices at all. That’s awesome! And that’s more rare than it sounds. Resisting the pull of daily or even monthly market moves, and instead focusing on the quality and trajectory of the underlying businesses – that’s the business owner mindset in action. It’s easy to say, much harder to practice. But the ability to tune out short-term noise is one of the few genuine edges that individual investors can still have.

There’s still dry powder left to deploy, and I’ll continue looking for additions that can strengthen the portfolio without weakening its integrity. The world won’t run out of good businesses or temporary dislocations – but our job is to recognize the difference between noise and signal, to keep studying, and to let the best ideas earn their way into the portfolio.

Thanks again for your trust and interest in the process. As always, I’m happy to discuss anything in more detail if something seems unclear – or if curiosity strikes.

René

Love the investor letters for your parents 🙂 I do similar for a few friends and family through Etoro. Have you ever considered re-creating this portfolio on Etoro where other investors can "copy" you (invest with you) and you can grow AUM and earn income?

Nice write up - thanks for sharing. Not sure I understand the Brockhaus investment rationale, seems like you are hoping the team “wakes up” from its slumber and starts acquiring again. Seems strange that it is not executing on it’s core value driver. Position sizing is a very interesting topic. Given Zalaris’ characteristics, were you tempted to have a higher allocation? Thanks again for sharing this.