[FREE] The Next Subprime? Jeffrey Gundlach’s Deeply Bearish Take On Private Credit

7 Insights That Forced Me To Re-Think A Few Things

Note: The voiceover above is a custom-made, slightly adapted version of the blog post, edited for a smoother and more engaging listening experience. It’s one of the perks available to paid subscribers, as I’m always focused on adding as much value to my subscribers as possible. Enjoy!

Jeffrey Gundlach is one of the very few macro thinkers I still pay close attention to as a bottom-up investor.

In a world full of loud, vague, recycled macro takes, he consistently delivers something rarer: actual insight!

The man has been doing this for multiple decades, has a documented hit rate, openly talks about the years he’s been wrong, and still manages to fire off sharper observations than most strategists half his age.

Speaking of age – how is he 66 years old and looking younger and more energised than a lot of people in their fifties? If there’s a longevity ETF that includes whatever Gundlach is doing, I’d like to know about it.

What I’ve always appreciated is his transparency. He calls himself a “straight shooter” in the interview, and that’s not an exaggeration. There’s no/little hedging for marketing purposes, no softening of the edges to keep everybody comfortable. He tells you what he thinks, why he thinks it, and where he might be wrong. And I genuinely believe he’s underappreciated by the broader investing community. You may not always agree with him, but he will absolutely force you to think.

I’ve unpacked some of his macro takes in past posts (such as the one linked below), and judging by how this most recent interview went, I’ll probably keep doing so in the future. If you don’t want to miss those posts, make sure to subscribe.

[FREE] Everything You Thought Was Safe… Isn’t Anymore! – Jeffrey Gundlach Unpacks the Shift

When Jeffrey Gundlach speaks, I listen. Not because I expect him to be right about everything – no one is – but because he has an uncanny ability to see the deeper shifts behind the noise.

Some interviews add a datapoint. Others force you to revisit the mental model itself. Jeffrey Gundlach’s appearance on Odd Lots (a Bloomberg podcast) falls squarely into the second category. It’s not a clean, single macro “call.” It’s a collection of somewhat uncomfortable ideas that, taken together, paint a picture of a system that’s running out of easy options.

In what follows, I want to walk through the key themes that stood out to me – rates, private credit, fiscal sustainability and potential rate manipulation, portfolio construction, the art of changing your mind, and his thought experiment on “perfect foresight.”

I’ll quote Gundlach where it helps, but the focus is on summarizing and unpacking what he’s really saying and what it might mean for your own positioning. I’ll cover seven insights in total.

Join the private WhatsApp community!

Discuss stock ideas, ask questions, and get behind-the-scenes thoughts in real-time.

Available exclusively for paid subscribers. Want in? Choose the annual subscription plan + reply with your number (more details in the welcome email).PS: Using the app on iOS? Apple doesn’t allow in-app subscriptions without a big fee. To keep things fair and pay a lower subscription price, I recommend just heading to the site in your browser (desktop or mobile) to subscribe.

1. A Broken Playbook? When Rate Cuts Don’t Pull Long Yields Down

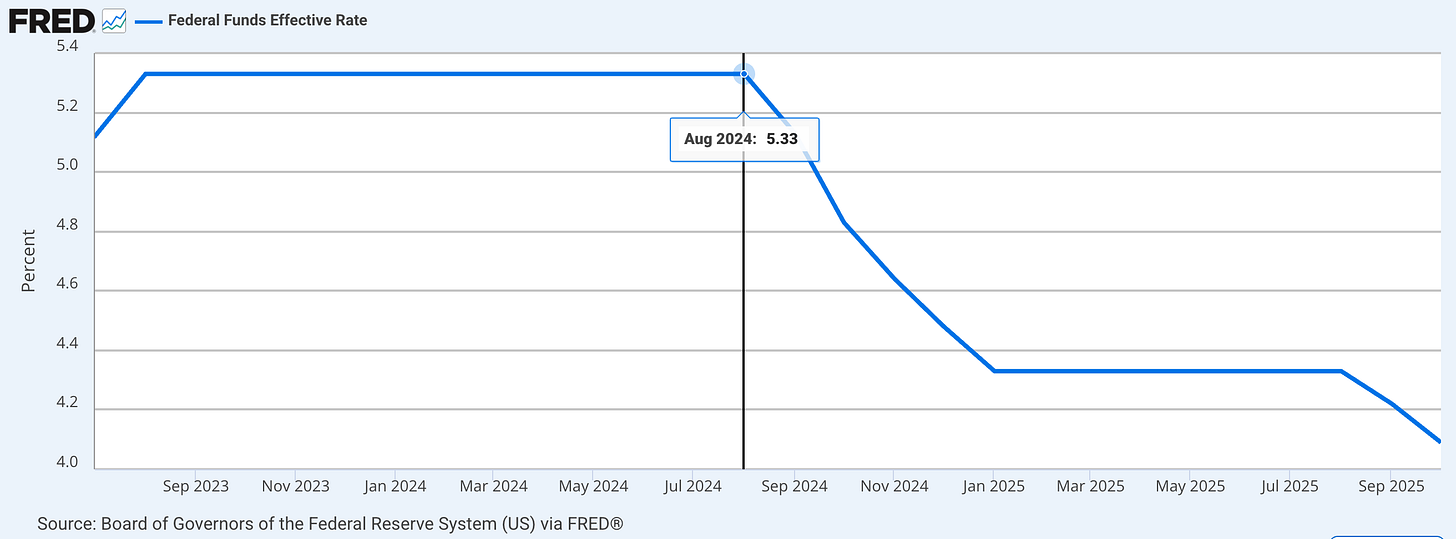

Historically, once the Fed starts cutting, the rest of the curve eventually follows. Short rates fall by definition, and longer maturities typically drift lower as the market prices weaker growth and lower inflation.

“[H]istorically when the Fed cuts interest rates, of course, short term interest rates decline definitionally at the Fed funds level, but also two-year Treasury rates decline, five-year Treasury rates decline. In effect, long-term Treasury rates have always declined, subsequent to the first cut by the Federal Reserve, and particularly when you’re in a sequence of Federal Reserve cuts.“

This cycle is different.

Gundlach highlights that since the Fed began cutting, “all interest rates outside of the two-year are higher than they were before the Fed’s first rate cut. That’s just never happened historically.”

That isn’t a footnote. For years, he has argued that “the secular decline in interest rates at the long-term maturities is over,” and recent price action is precisely the kind of confirmation he’s been looking for.

Long yields are no longer treating Fed cuts as a cue to behave.

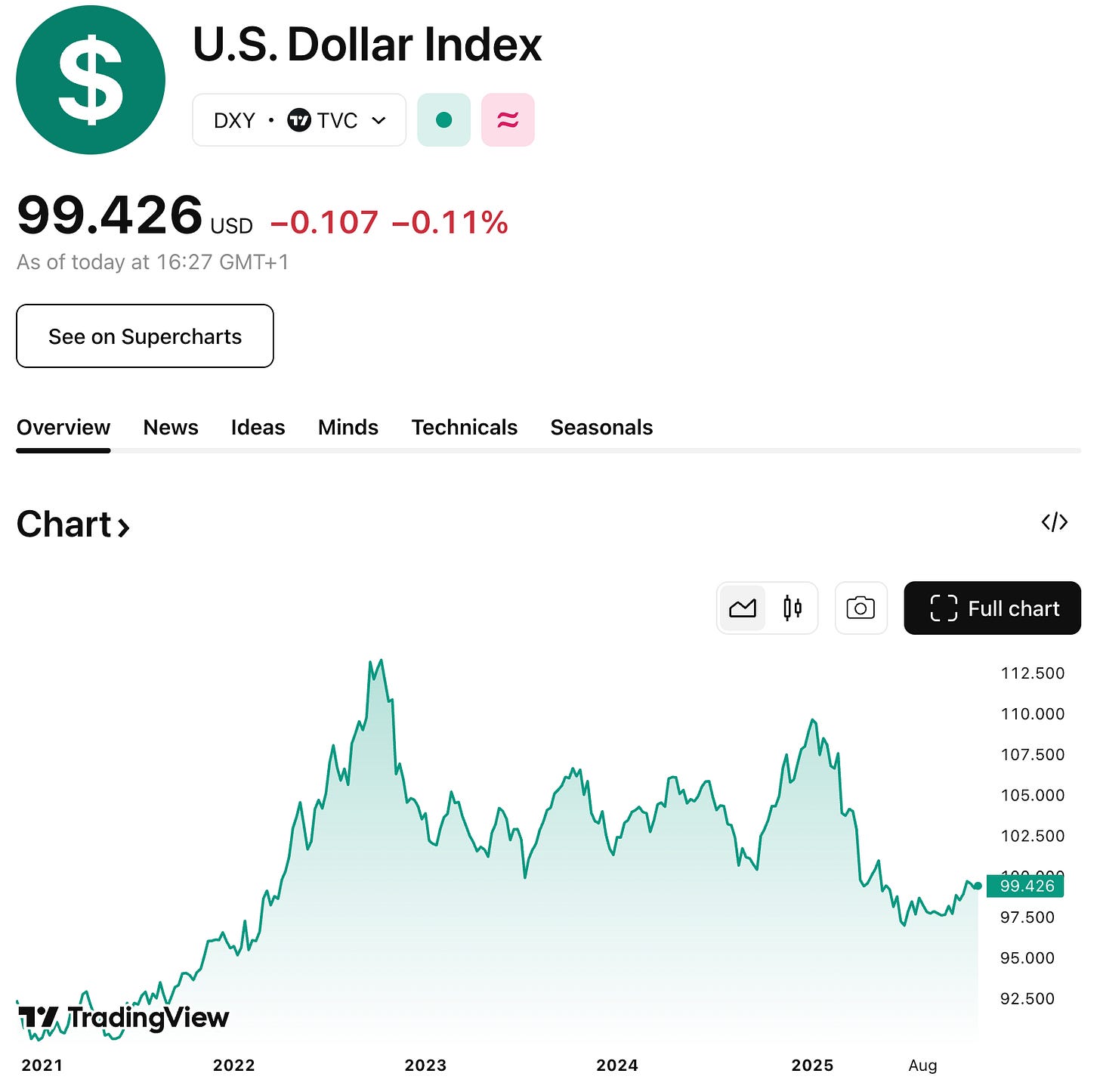

A second anomaly is the dollar’s behavior during equity drawdowns. In the “tariff tantrum” correction earlier this year, instead of rallying as a safe haven, the dollar fell. By Gundlach’s count, in the 12 previous corrections of at least 10% in the S&P 500, the dollar “usually goes up by around 8%.” This time, it went down by about 10%.

For him, these two breaks – the long end ignoring cuts, and the dollar failing in its traditional crisis role – point in the same direction: the old ZIRP-era playbook is done. The market is starting to care more about structural issues like fiscal sustainability and long-term inflation pressure than about short-term Fed tweaks.

Before we dive back in, a quick note…

Want to invest in the one edge that compounds forever? Join hundreds of investors sharpening their thinking, avoiding mistakes, and discovering quality before the crowd. Subscribe to CompoundWithRene and become a better investor over time.

2. Private Credit & Private Equity: New Crisis Candidates?

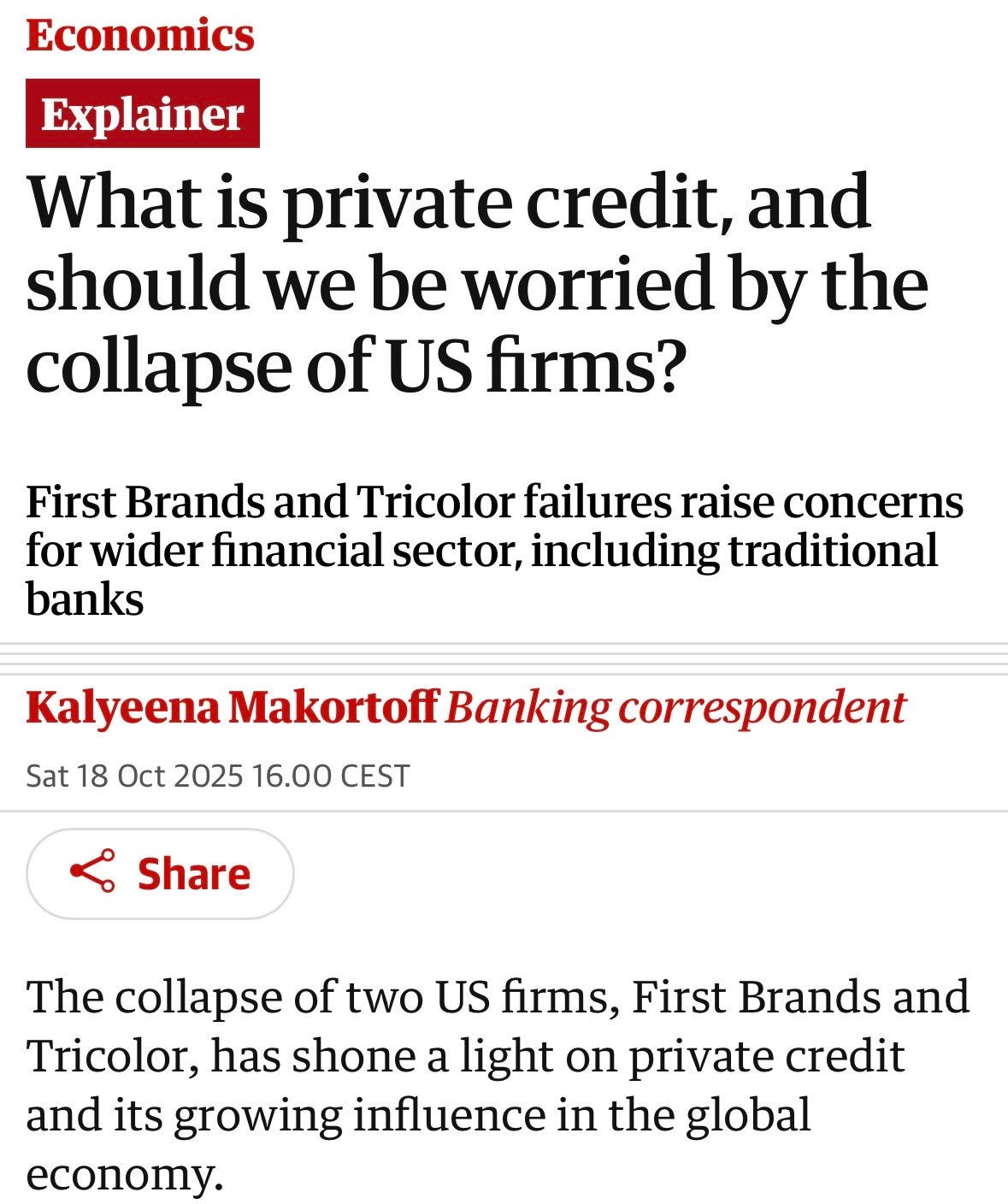

The most scathing part of the interview is his take on private credit.

He doesn’t just think it’s overheated. He thinks it’s the most likely epicenter of the next real crisis. Yes, you read that right!

The starting observation is where the bad lending has migrated. Before the GFC, a lot of questionable structures were in the public markets and securitizations. Today, he argues, “in recent years, the garbage lending has not gone to the public markets. The garbage lending has gone to these private markets and private credit has been very popular and is now increasingly been over allocated to by large asset pools.”

That would already be worrying, but the way the product is sold and marked makes it more dangerous. The core marketing pitch is a Sharpe ratio story: similar or slightly better returns than public credit, with much lower volatility.

Gundlach’s response is brutal: “If you don’t mark to market, there’s no volatility.”

He points out that this is just a repackaging of the same trick private equity has used for years – when the S&P falls from 100 to 50, PE marks drift from 100 to 80; when the index recovers to 100, PE gets marked back to 100. Same long-term return, but recorded volatility looks much lower because the path is smoothed with stale marks.

The recent Renovo example crystallises how there’s a lot of hidden fragility:

“And now it’s very fascinating that this Renovo in the article today it basically said that they had a chapter seven filing and bankruptcy filing and their asset, the their liabilities were listed as being between 100 and $500 million. You just, you know, you check a box, you’ll forget a specific number. So there’s ranges and the whole range that their liabilities were in was between 100 and $500 million.”

Gundlach’s line is memorable: “It’s like there’s only two prices for private markets, 100 and 0.” When your pricing system only recognises perfection or collapse, you don’t have risk management, you have theatre.

The packaging makes it worse. There are now vehicles offering “Main Street” access to private credit – a product design he describes as “the perfect mismatch of no liquidity with a vehicle that promises liquidity.” Under benign conditions, everybody can pretend this works. Once redemptions pick up, the daily price will be the only adjustment valve, and it can gap lower very quickly.

His verdict is clear: “the next big crisis in the financial markets is going to be private credit. It has the same trappings as subprime mortgage repackaging had back in 2006.”

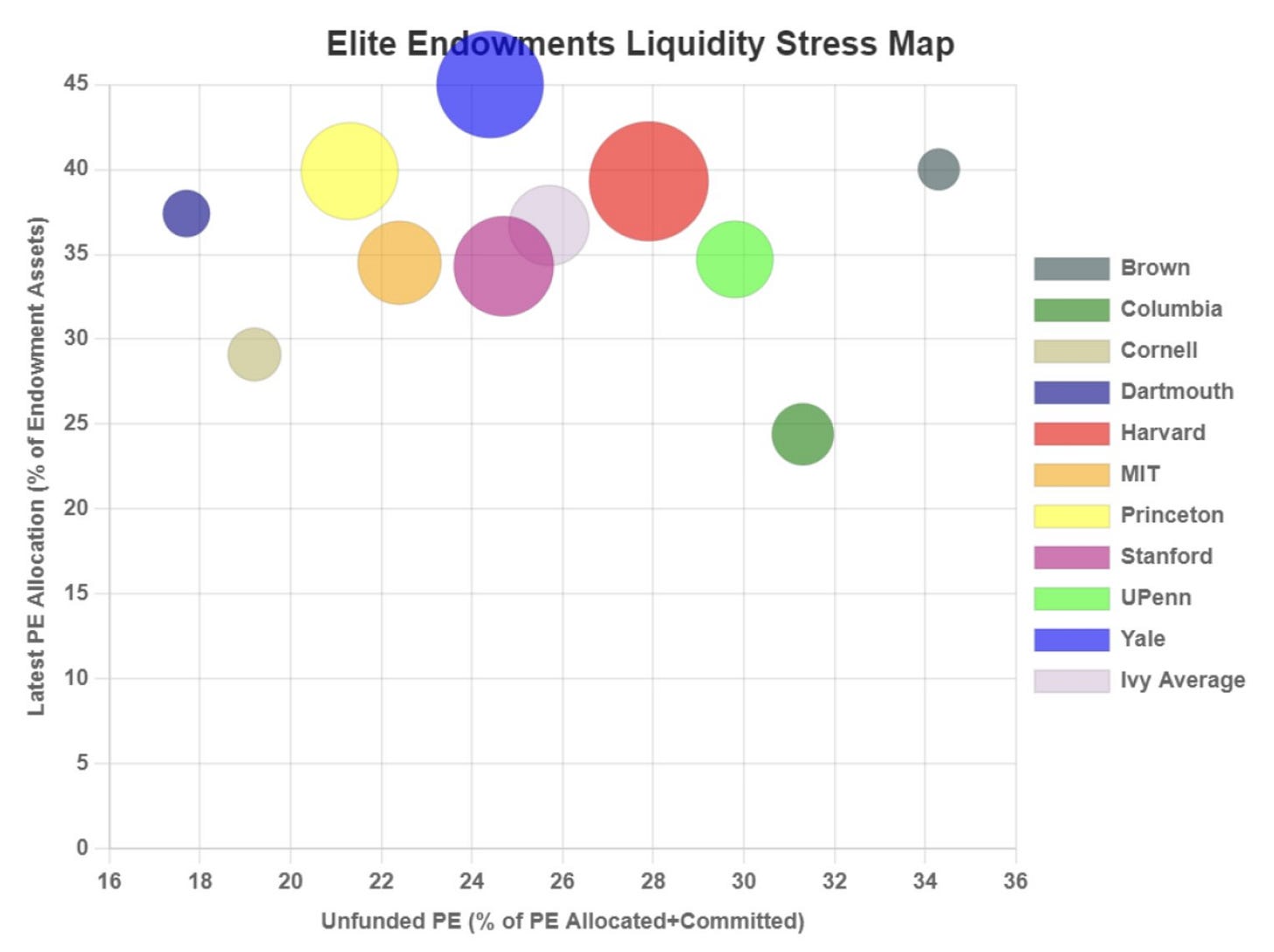

Then there’s Harvard as an example of the liquidity in PE:

“I remember Harvard University, for example. They’ve got like a 50 odd billion dollar endowment, and their donors pulled back when they had uprisings on campus, and the donors didn’t like what was going on. So they stopped donating for a while. And Harvard had no money, a $50 billion endowment, and they couldn’t pay salaries. They couldn’t pay the late bills, they couldn’t pay basic maintenance. They had to go to the bond market to borrow. They tried to borrow about $4 billion, I think. I think they got away with about $2.5 billion. But it’s fascinating that you have a huge asset pool that doesn’t have liquidity to pay the bills.”

The practical takeaway from all of this for me is not that every private credit deal is doomed. It’s that the combination of optimistic marks, leverage on top of leverage, liquidity promises that cannot be honoured in stress, and mass marketing stories built around “low volatility income” and “safe high returns in PE” are a classic late-cycle pattern.

“German retail investors represent one of the world’s largest untapped pools of wealth, and private equity firms are eager to gain access.” – Claudio de Sanctis, Head of Retail Banking at Deutsche Bank.

We’ve already seen a few “cockroach” defaults. The odds that those are isolated incidents look low. How soon exactly something will break, Gundlach cannot predict though:

“Now, it took a couple of years for it to totally unravel. So this stuff doesn’t happen in a week or a year even. But I’m very negative on that.”

3. The Fiscal Doom Loop – And Why Rates May Be Manipulated Next

Gundlach’s bearishness on long-dated Treasuries is anchored in arithmetic, not just vibes. The U.S. deficit is already increasing at a rate of roughly 6% of GDP, a level that historically coincided with deep recessions.

For comparison, during normal (non-recession) years, the U.S. deficit has averaged around 2-3% of GDP in many years.

But in downturns, that deficit tends to blow out. Over the last half-century, it usually widens by 4–5 percentage points of GDP in a recession. In the GFC and Covid episodes, it moved closer to 8 points. So a recessionary deficit in the 10–12% of GDP range isn’t a wild tail scenario – it’s a plausible base case if nothing changes. That’s where interest expense starts to consume the system.

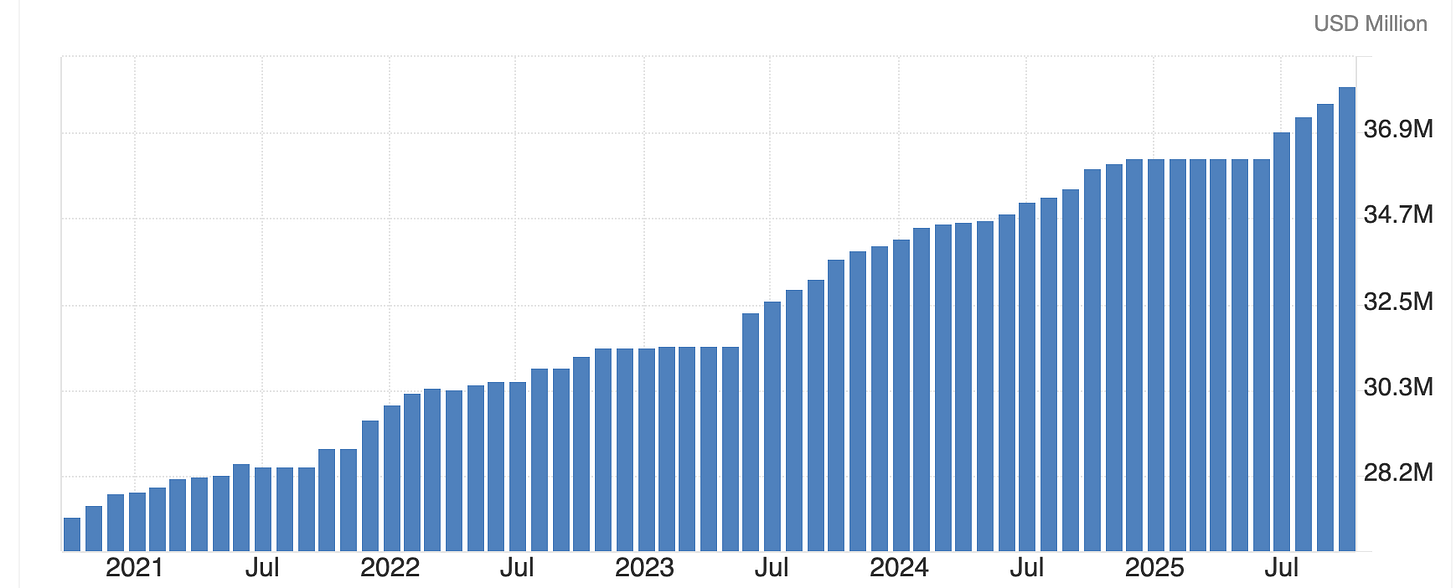

Today, he notes, roughly “about 1.4, $1.5 trillion of the $7 trillion budget is now interest expense,” with only around $5 trillion in tax receipts (i.e. a $2 trillion budget deficit).

In other words, about 30% of revenues already go to interest. And that share is almost mechanically set to rise, because the bonds rolling off in the next few years still carry an average coupon “a little bit below 3%,” while new issuance happens at much higher yields.

At Jim Grant’s 40th anniversary conference, Gundlach walked through a scenario where deficits and rates stay elevated. With “plausible” but pessimistic assumptions, he arrives at a world around 2030 where “we have 60% of all tax receipts going to interest expense.”

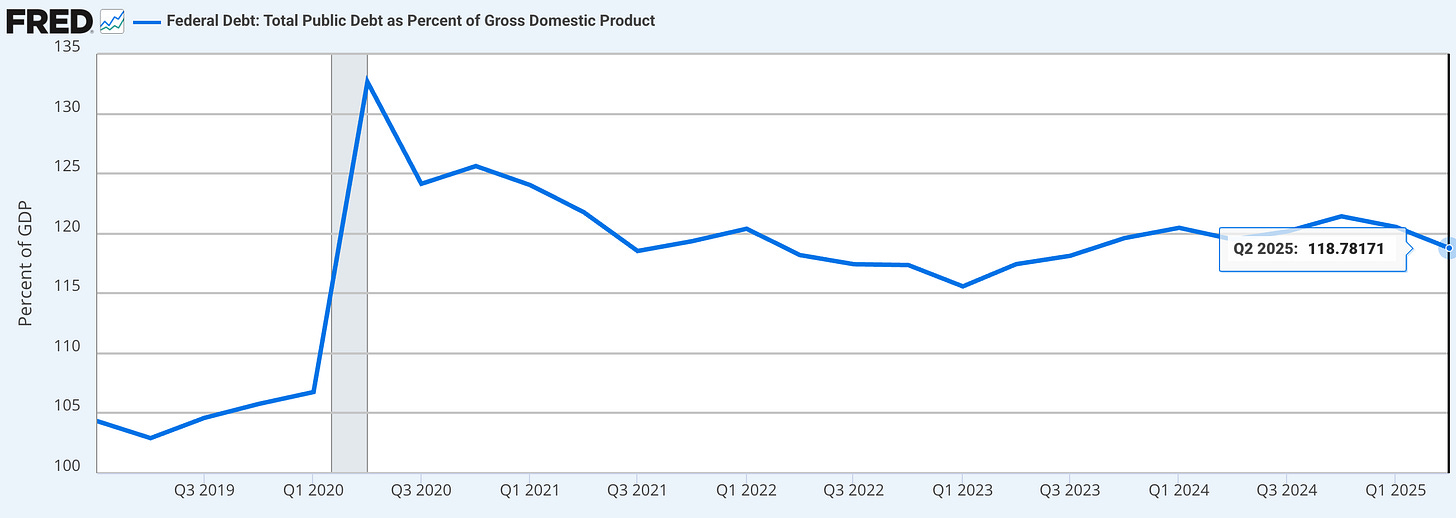

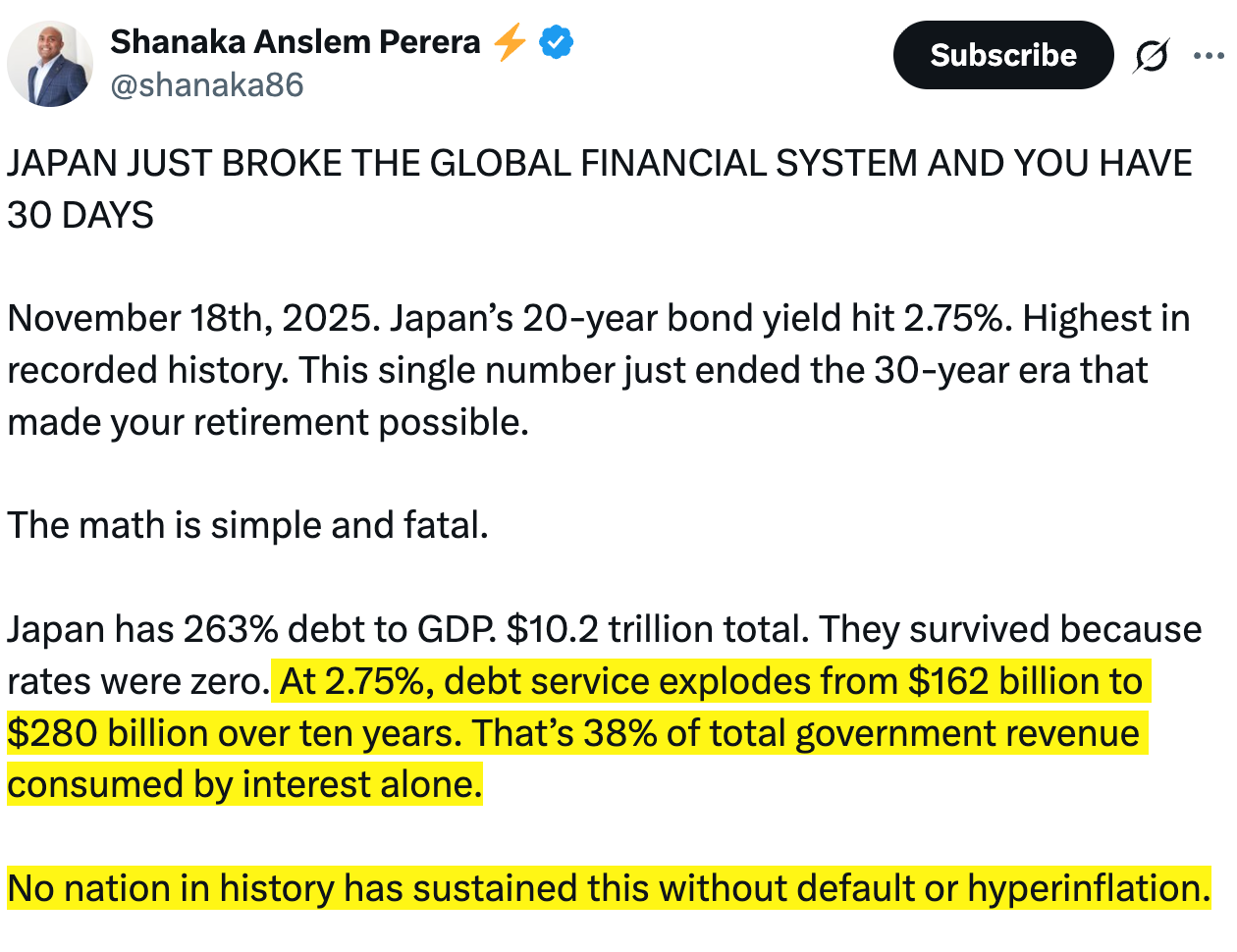

That sounds absurd until you consider what could be happening in Japan at a >200% debt-to-GDP ratio at lower rates (the US currently sits at 118%):

According to Gundlach, if you push the assumptions harder – “what if interest rates go up to 9% on treasuries? And what if the budget deficit goes to 12% of GDP and you make these kinds of, you know, pessimistic assumptions?“ – and the model spits out an absurd result: interest costs equal to 120% of tax revenues.

“Of course that is impossible,” as he puts it, which means something has to give – either the fiscal path or the rules of the market itself.

That’s where his views on potential rate manipulation come in. He has been saying for almost two years that “we cannot afford the market to set interest rates if the deficit spending continues.” His base case is some form of explicit intervention designed to cap long yields: “What has to happen is some sort of drastic measures. And I’m not exactly sure what those drastic measures are going to be. There’s a number of candidates for them.” One candidate is full-blown yield curve control, echoing the U.S. in the 1940s and Japan more recently. Back then, the U.S. kept long bonds at 2.5% even as inflation pushed towards 8%. Japan spent years with a zero-yield cap, with the Bank of Japan effectively the only natural buyer of its government debt.

This anecdote made me laugh out loud:

“I actually had a meeting with, the guy that ran the biggest pension plan in the world as one of the Japanese public pension plans, and I was really anxious to sit down with them. And I said, I really want to ask you this question, do you actually own these negative yielding jobs? And he actually laughed out loud when asked, what’s he said, of course, now nobody owns them except the Bank of Japan and the and the institutions that are forced to buy them by the Bank of Japan.”

Another lever would be targeted support for mortgage rates – “they could absolutely buy Ginnie Maes, Fannie Maes, Freddie Macs… and drive those yields down much closer to where Treasury yields are.”

Yet another, more radical option is outright restructuring of Treasury terms. He references a white paper suggesting special treatment for “foreign” holders, but points out that once the taboo is broken the logic can easily be extended: “Why put the word foreigners in there? Why not just say we’re going to restructure the Treasury debt full stop?”

His toy example is brutal in its simplicity: “All the treasuries that exist today, we’re changing their coupons. The ones that have a coupon above one, the coupon is now one.” That would slash interest expense, devastate existing bondholders, and likely shut the government out of voluntary borrowing “for a couple of generations.”

Against that backdrop, his reaction to the current political flirtation with a $2,000 “tariff dividend” to every American is revealing. With tariffs raising a few hundred billion dollars a year, the idea is to send $2,000 checks to households. Gundlach’s verdict is blunt: “We don’t have any money. We’re borrowing $2 trillion. We don’t have $2,000 to throw away at people again.”

We’ve just lived through 2020–2022, when aggressive money-financed transfers helped push inflation to 9.1%. In his eyes, the fact that such proposals are back on the table shows how unserious the debate still is.

Put together, this is why he says “long-term treasuries look vulnerable.” If you believe the system will eventually move towards some combination of higher inflation, explicit caps on yields, distortive interventions and/or restructuring, then owning a lot of long-duration nominal claims on that system doesn’t look particularly attractive.

However, he still likes “short-term treasuries because I think the Fed is likely to cut interest rates, and that definitionally leads to lower interest rates on, say, five years and in maturities.“

4. Rethinking 60/40: What A “Defensive” Portfolio Looks Like To Him

So what does he do with all of this? At a high level, he thinks “financial assets broadly should be lower allocated, have a lower allocation than typical” right now. The traditional 60/40 equity-bond portfolio implies a 100% allocation to financial assets.

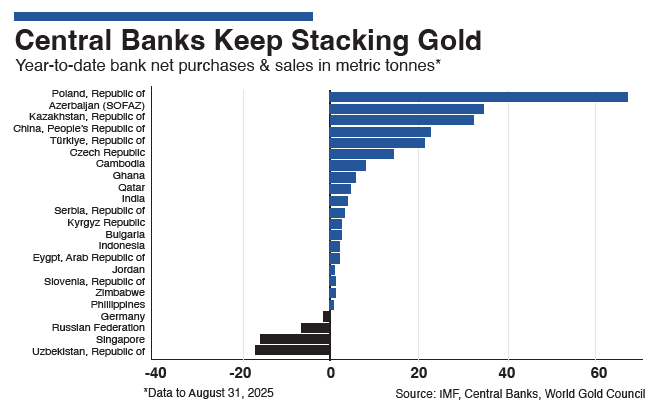

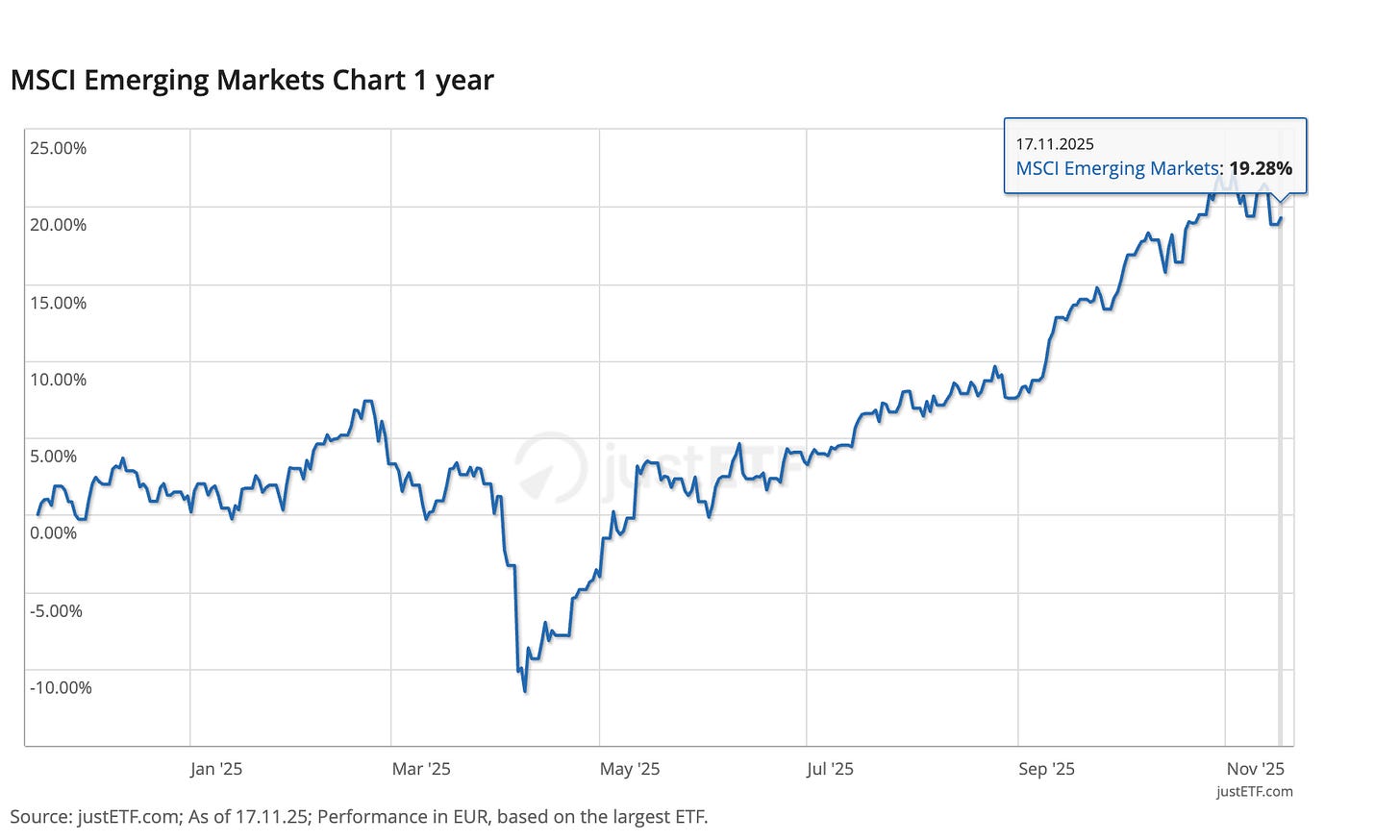

In his view, that’s too high given current valuations and macro fragilities. For equities, he suggests “investors should have maximum 40%” in stocks today, and even that should be tilted away from the U.S. towards non-U.S. markets. For a dollar-based investor, he sees better opportunities in European and emerging markets. EM local stocks and European indices have already outperformed this year once you factor in currency moves. On the fixed income side, he still sees a role, but smaller than the traditional 40%. He proposes “about 25%” in bonds, again with a meaningful non-dollar component – especially emerging-market fixed income, which he notes has been “by far the highest performing sector for dollar based investors in the fixed income market this year.”

The interesting part is what fills the remaining 35–40%. For several years, Gundlach has been vocal about gold and real assets. In his annual “Roundtable Prime” discussion, he made gold his “number one best idea,” arguing that it has graduated into a mainstream asset class: “I think gold is now a real asset class. I think people are allocating to gold, not just the survivalists… people who are actually allocating real money because it’s real value.”

Reading recommendation:

After a strong run, he thinks the very aggressive allocation he once advocated – 25% in gold and land-like assets – is probably too high, and talks more about something like 15% (“or something like that”) today. The rest, in his mind, belongs in cash. That’s not because he’s excited about holding bills forever, but because he thinks “valuations are just incredibly high” and that the U.S. equity market is “among the least healthy in my entire career” on classic metrics like P/E, CAPE, and overall speculative tone.

He views the AI and data-center boom as another mania. To make the point, he uses a historical analogy that I really like. The electrification of homes was arguably one of the biggest economic and social transformations of the last 150 years. Investors spotted it early. Electricity stocks had a massive run. But their outperformance versus the rest of the market actually peaked in 1911 – long before electrification was widespread.

The idea is simple: truly transformative technologies can be real and still produce index-crushing returns far earlier than you’d think, as investors wildly over-discount the future.

5. Changing Your Mind: Why It’s Essential – And Why So Few People Do It

One theme that runs through the interview, and that I think is underappreciated, is how hard it is to genuinely change your mind in markets.

Gundlach uses his own stance on the dollar to illustrate it. For decades, he was a committed strong-dollar guy: “I was 100% dollar. I would own no foreign currencies for decades.” That was part of his identity as an investor.

About 18 months ago, he finally flipped. He “had to pull the trigger” and accept that the strong-dollar paradigm he’d benefited from “is [not] intact any longer.”

The way he describes that internal conflict is very human:

“You wake up in the morning and you look in the mirror and say, I’m looking at a strong dollar guy. And then all of a sudden the next day you say, I’m looking at a guy that’s no longer confident in a strong dollar… who am I?”

That’s the emotional cost of a genuine regime shift. You’re not just changing a position; you’re rewriting the story you tell about yourself.

Now put yourself in the shoes of a typical financial advisor or portfolio manager. The incentives are stacked against meaningful change. The example Gundlach uses is assume you bought something like Apple at $5 and it’s now at $700, that line item makes every client meeting easier. You can point to it and say, “Look at this cost five, last price 700, I am working for you.”

The day you sell it, you remove that story from the statement. You’re no longer “the person who bought Apple at $5,” you’re just the person who used to have a great call. Humans hate that. They cling to the past winner as social proof.

Gundlach’s point is that this is dangerous. The very positions that have made you look smart and employable are the ones you’re least willing to kill, even when the underlying thesis changes. The incentive structure pushes people to project past successes into the future, long after the structural drivers have shifted.

His own shift away from dollar maximalism, and towards more non-U.S. risk and currency exposure, is a case study in doing the uncomfortable thing when the evidence forces you to.

From my perspective, that’s one of the more useful meta-lessons: it’s not enough to be theoretically open-minded. You have to be willing to dismantle the very positions that make you look good in front of clients, friends, and followers. Often, that’s what leads to future success in this business.

6. When The Rules Change Mid-Game

Another big theme is that “the rules can be changed” much faster and more radically than most investors like to think. Gundlach points to two recent episodes as proof:

During the GFC, the authorities effectively overrode the legal terms of mortgage securitisations by modifying mortgages in ways that weren’t contemplated in the prospectuses.

In 2020, the Fed crossed what many saw as a bright line by buying corporate bonds.

He admits that the “magnitude of money printing that occurred in 2020, 2021, 2022” and the fact that the Fed “broke the law and bought corporate bonds” genuinely surprised him. It probably shouldn’t have, but it did. Once you internalize that, more radical ideas stop looking like science fiction. The discussed idea of a yield curve control framework, comprehensive restructuring of Treasury terms, different treatment for “foreign” holders, targeted interventions in mortgages – all of these move from unthinkable to “under certain conditions, quite possible.”

That’s why he keeps hammering the point that paying the existing debt back in today’s dollars is impossible, and that something like a rewrite of the rulebook is likely. The fact that ideas for new “schemes” in the same spirit keep popping up tells him that the political impulse hasn’t changed.

Add to that the collapse in institutional trust among younger cohorts. Surveys show that people under 35 increasingly “don’t believe in the institutions of this country at all.” They don’t think they’ll ever replicate the baby-boomer experience – not in housing, not in wealth building, not in career stability. That’s fertile ground for more radical redistributive policies.

One idea he throws out – half joking, half serious – is an “age tax,” a surtax on those over 55 based on the argument that they had a vastly better environment for wealth accumulation and should “give some of that back.” You don’t have to take every one of these ideas literally.

The point is that when a system’s arithmetic stops working, and when trust in its institutions collapses, the range of plausible policy outcomes widens a lot. As investors, ignoring that and assuming a clean, rules-based path back to stability is probably the bigger risk.

7. The “Perfect Foresight” Experiment: Why Being Right Isn’t Enough

The last piece I want to highlight is about process rather than macro. Apparently, early in his career, Gundlach was tasked with an odd thought experiment:

What would happen if you had “perfect foresight” in markets?

Using historical data for stocks, bonds, real estate, commodities and so on, he simulated a strategy that, at the start of every year, picks the asset class that will have the highest return over the next five years. You literally can’t do better in terms of long-term selection.

The surprising result was that, even with that impossible advantage, you’d likely go out of business!

The reason is timing. In many cases, the asset class that ends up being the five-year winner is a poor performer in the first one or two years. Returns are back-end loaded. A client looking at year-one and year-two performance wouldn’t see a genius with perfect foresight. They’d see underperformance and fire you.

As he puts it, “we cannot invest other people’s money with a five-year horizon.” The business reality just doesn’t allow it. On the other hand, he thinks most managers go too far in the other direction – constantly tweaking positions with a de-facto one-week or one-month horizon. The odds of being consistently right at that frequency are tiny, even if your macro compass is good.

After experimenting with different horizons, he concluded that the “sweet spot” is “between 18 months and two years.” Long enough for big structural views to have a chance to play out, short enough that clients don’t necessarily pull the plug before anything happens.

Measured over that kind of window, across a large number of decisions, he says he’s ended up with “a 70% hit rate.” The flip side is that he’s wrong 30% of the time, which means “I’ve been at this for over 40 years, so I’ve been wrong for more than 12 years.”

The key is that those bad years weren’t consecutive. In his words, “three years is when everyone pulls the plug. If you underperform year one, year two, when you’re three, you’re gone.”

He also reminds us how painful it can be to live through the “wrong” part of being early. He turned “maximum negative” on the Nasdaq on 30 September 1999 and “looked like a moron” three months later as the index surged another 80%. “But if you had gone short the Nasdaq September 30th of 1999, 18 months later, you had a profit of 64%, even though it went up 80% in the first three months, it dropped.“

The intervening period is where careers either survive or die. The big takeaway for me is that having a strong view – on private credit, on long rates, on the dollar – isn’t enough. You need to be explicit about your time horizon, realistic about your hit rate, and honest about how much interim pain you and your clients can tolerate.

The “perfect foresight” experiment is a nice reminder that even the best long-term calls can look disastrously wrong for long enough to get you fired.

Closing Thoughts

Individually, none of these Gundlach themes are completely new. People have worried about the US deficits for years. The death of 60/40 and the question of dollar hegemony have both been debated at length. What makes this interview interesting to me, though, is how a more fragile environment is seemingly forming: Long rates rising despite cuts. A fiscal path that doesn’t add up under current rules. Historically high valuations. Private markets showing more 100-to-0 moments. Political proposals like $2,000 “tariff dividends” that ignore freshly learned inflation lessons. A policymaking culture that has already shown it’s willing to bend or break supposedly hard constraints. And sitting on top of that, an investing industry whose incentive structure makes genuine mind-changes rare, and whose clients would fire even an omniscient manager with a five-year horizon.

You don’t have to agree with every detail of Gundlach’s view to take the core message seriously: we are not in a benign, mean-reverting cycle where old correlations and old playbooks can be trusted blindly.

For me, the value of this interview isn’t that it hands me a ready-made asset allocation. It’s that it forces me to re-examine some comfortable assumptions – about what’s safe, what’s liquid, what’s “diversified,” how stable the rules really are, and how honest I am with myself about time horizons and the difficulty of changing my mind when the world actually does.

![[FREE] Everything You Thought Was Safe… Isn’t Anymore! – Jeffrey Gundlach Unpacks the Shift](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!dfFS!,w_280,h_280,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F65435594-ad93-4227-962a-376c4084289e_1024x1024.png)