Forget ROIC! This Metric Tells You How Well a Business Really Compounds

The Concept of ROIGI as an Evolution of ROIC & ROIIC

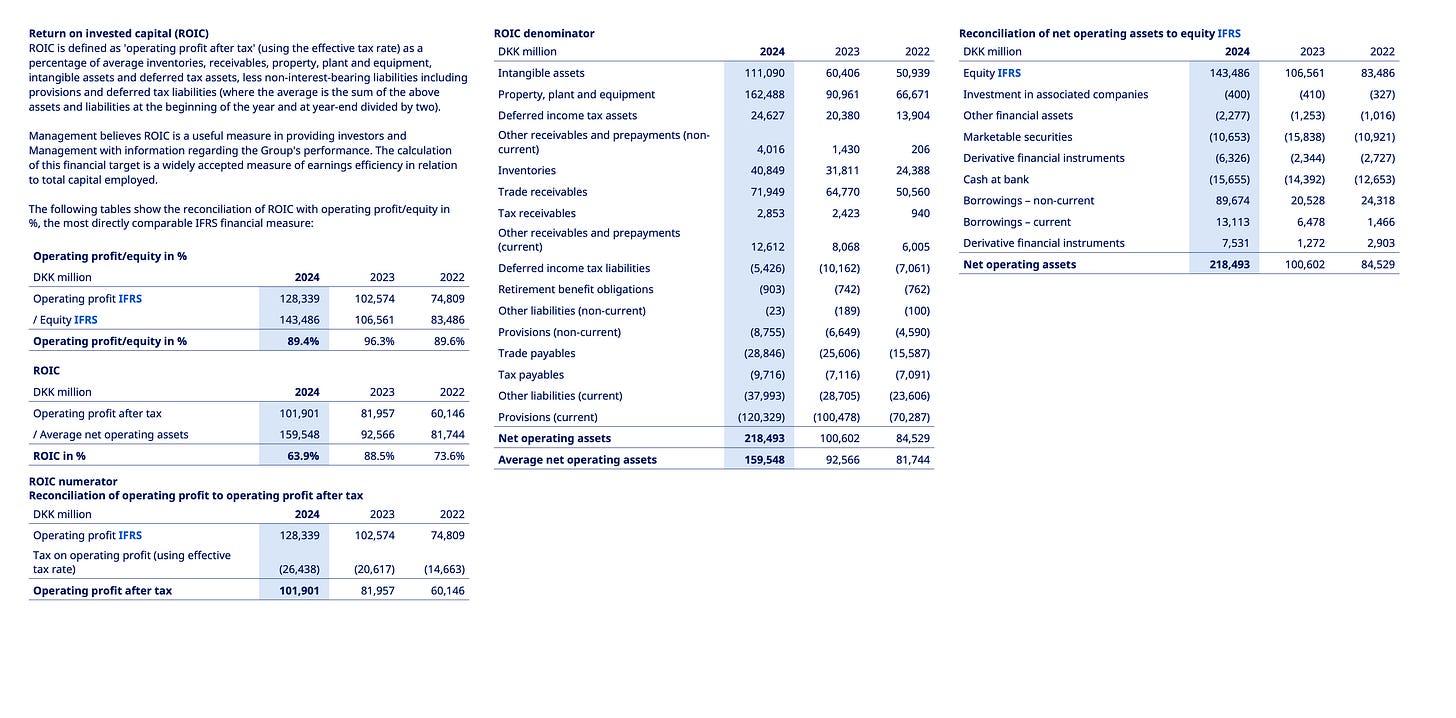

If you’ve been following my writing, you might’ve read my last post on Novo Nordisk’s “true free cash flow” – an attempt to adjust for some of the accounting noise and better isolate what a business is really generating after sustaining itself.

This post builds on that effort, but now I want to take it a step further. Specifically, I want to understand how efficiently Novo has been reinvesting its incremental capital – not just any capital, but capital earmarked for growth.

In other words, I’m trying to calculate what I’ll call the Return on Incremental Growth Investment, or ROIGI.

Now, here’s where it gets interesting: the returns companies earn on reinvested capital are often much more nuanced than headline numbers suggest. It’s not as simple as plugging a few figures into a spreadsheet and declaring the business a 20% return machine. There are layers to this.

Yes, there’s the well-known distinction between ROIC and ROIIC and how returns tend to evolve as a company moves through different stages of its life cycle. But there’s more. Even within a single business, the returns on reinvestment can vary significantly depending on the type of project, the geography, the business line, or even the competitive dynamics in that particular pocket of the market.

A company might earn incredible returns launching a new product in its home market, while simultaneously burning capital trying to expand in a region where it lacks distribution strength or brand equity.

The headline return number rarely captures that internal dispersion – but it matters. A lot.

So What Are We Trying to Understand Here?

The goal is to estimate how much additional free cash flow Novo Nordisk generated between 2017 and 2024 for every dollar it deployed toward growth, not maintenance.

This is more than an academic exercise. Getting a sense for whether a company is deploying its resources effectively tells you something fundamental about its quality as a compounder. Done right, this can help you distinguish between a stock that has momentum and a business that has structural reinvestment advantages.

Let me be clear: this is not about being precise to the decimal point. That’s not possible. There’s (unfortunately) no official line item in financial statements labeled “growth investments only.” Quite a lot of assumptions will be made. Some lines will be blurry. But that’s okay. My goal is not mathematical perfection – it’s directional truth. I want to get a sense of the return Novo NVO 0.00%↑ has been getting on its growth spend over this period of substantial reinvestment.

Interestingly, a comment on my previous post addressed the point I’m making with this article. The reader wrote:

“As a slight counter: as a company grows wealthy, it has more money to throw at new ideas. Is it more successful at picking the new ideas? Will the research pan out, just because more resources are going towards it? I would point towards Meta and the buckets it has thrown at virtual reality, which still seems to have as much practical application as crypto at this point.”

This is exactly the question ROIGI seeks to address. What are the returns a business earned on reinvestments more recently – that’s as close as we get to anticipting future returns on reinvestments. How successful has management reployed capital over the last 3, 5, 7, or 10 years?

Just because a company spends more doesn’t mean it earns more. Efficiency matters.

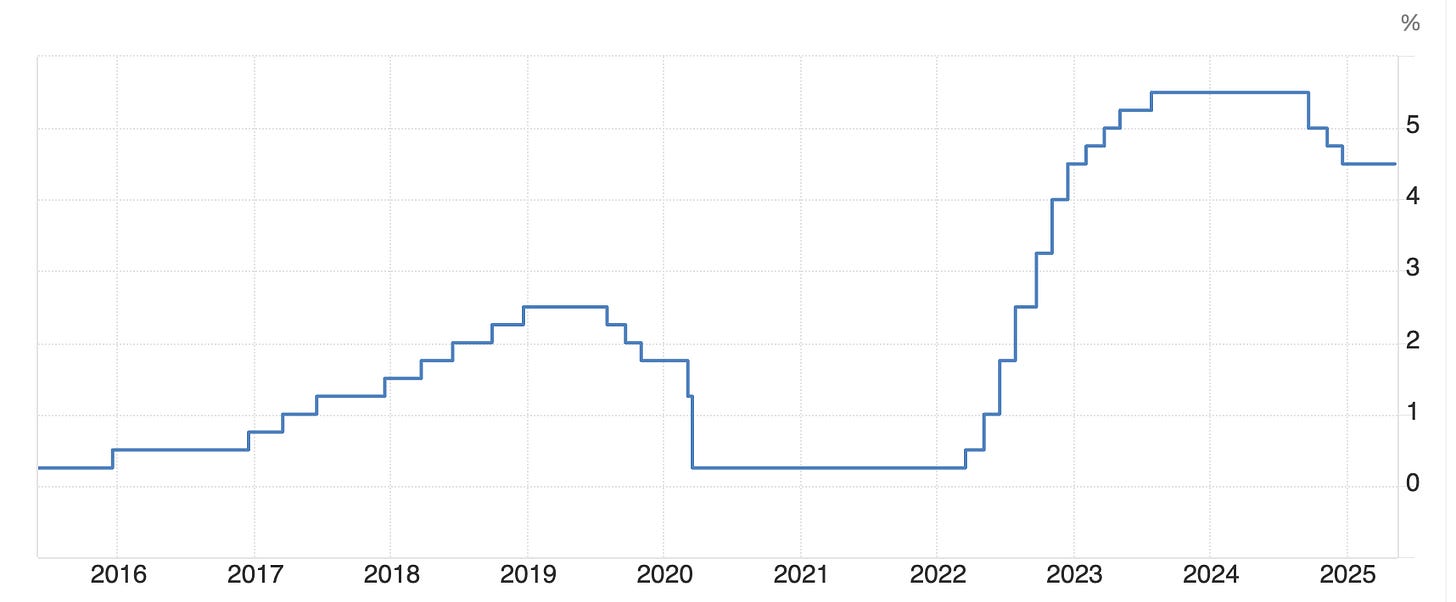

And in an environment where capital isn't free anymore, knowing how well growth capital translates into future cash flow is arguably more important than ever.

So that’s the plan. I'm going to walk you through the framework I used, the assumptions I made, the capital I counted, the cash flow I measured, and the math I ran. Then we’ll try to make sense of what it tells us – and what it doesn’t.

Before we dive back in, a quick note…

Want to compound your knowledge – and your wealth? Compound with René is for investors who think in decades, not headlines. If you’ve found value here, subscribing is the best way to stay in the loop, sharpen your thinking, avoid costly mistakes, and build long-term success – and to show that this kind of long-term, no-hype investing content is valuable.

Thank you for your support!

Part 1 – Why ROIGI > ROIC: A Better Way to Measure Growth Returns

Let me start with a confession: I used to think ROIC was the holy grail of business quality metrics. Most investors do at some point in time as they progress as business analysts – they overestimate their abilities (that’s something I discussed in my post on typical learnings trajectories in investing; read it here: “Logarithms, S-Curves, and the Truth About Gaining Investing Expertise!“).

And don’t get me wrong – ROIC still holds value (a lot of value!).

“The most important quality factor, and the one that Mr Market seems to reward the most, is return on capital — surprise surprise! ROC = value creation for all stakeholders of the company. The more value that’s created, the more benefits and rewards.” Tiho Brkan

But once you’ve looked at enough companies and tried to reverse-engineer what actually drives performance, you start to see the cracks.

The biggest issue with ROIC is that it tries to distill something complex and forward-looking – capital allocation – into a tidy, backward-looking, accounting-defined formula. In theory, it captures the return a company generates on the capital it employs. In practice, the number is often distorted by accounting artifacts, acquisitions, and all the stuff that gets dumped into the “invested capital” denominator.

This is where ROIGI comes in. Instead of asking “what is the return on ALL the capital the company has ever deployed,” I want to ask something more focused:

“How well has the company done with its NEW capital – specifically the capital it allocated for growth?”

This isn’t just semantics. It’s a shift in perspective. It separates the legacy business from the incremental engine. And in many cases, it’s the incremental engine that matters most.

Let’s bring in someone who’s done more thinking on this than most: Aswath Damodaran. In a podcast episode with Patrick O’Shaughnessy, he explained why ROIC often misleads more than it illuminates:

“I know it's become this magic bullet that people focus on. Every year, I actually compute the return on invested capital for every company on the face of the earth, 46,000 companies. So, I'm intimately aware of what accountants can do to screw up that number. I mean, I'll give you a classic example. Forget about using the return capital. Computing the return on invested capital for a company that grows through acquisitions is a nightmare. Why? Because acquisitions create debris. Goodwill, what do you do about that? What do you do if you pay with stock instead of cash? I can make a really bad company have a high return on capital if you give me enough accounting discretion to play that game. […]

The problem with return on invested capital is as a metric, it's designed for mature or declining companies. You can be a great growth company. Its return on invested capital can be either meaningless. […] For young companies, the ROIC becomes almost meaningless. So, if you have an investment strategy built around ROIC, remember, this is going to leave you with a portfolio of older and declining firms. ROIC is a backward-looking accounting number […] Keep that in perspective when your investment strategy is driven entirely by ROIC.”

That last part hit me hard: ROIC is a backward-looking accounting number. Exactly. That’s not what I want to base my thinking on, at least not exclusively.

Instead, I want to look at how effectively a company is deploying new money – capital earmarked for expanding the business, developing new products, entering new markets, or increasing capacity. My ROIGI metric attempts to isolate just that.

And while there’s some messiness involved (which I’ll get into in a moment), it has the potential to tell you a lot more about the health and future of a business than ROIC ever could.

It also has the advantage of being more adaptable to real-world business models. Think about R&D-heavy companies like Novo Nordisk. Most of their “capital” investments don’t show up on the balance sheet – they flow through the income statement as expenses. If you only focus on capitalized assets in your ROIC calc, you’ll miss a massive part of the picture.

John Huber puts this well:

“Of course, there are different ways to measure returns (you might use operating income, net income, free cash flow, etc...) and there are many ways to measure the capital that is employed. There are also 'investments' that don't always get categorized as capital investments but run through the income statement—things like advertising expenses or research and development (R&D) costs. To be accurate, you'd want to know what portion of advertising is needed to maintain current earning power (akin to ‘maintenance capex’). The portion above that number would be similar to ‘growth capex,’ which could be included when thinking about return on capital. R&D could be thought of the same way.”

This isn’t easy work. It requires judgment, estimates, and even a bit of courage to make assumptions where the data doesn’t give you a clean split. But in exchange, you get a better sense of what actually matters: how well the company is deploying its incremental resources.

So no – ROIGI isn’t perfect. But I’d argue it’s a step closer to reality than many of the more common formulas people cling to.