The AI Shockwave: Why Tech Is Riskier Now Than Ever Before

Why You Have to Rethink Tech in the Age of AI

The voiceover above is a custom-made, slightly adapted version of the blog post, edited for a smoother and more engaging listening experience. It’s one of the perks available to paid subscribers, as I’m always focused on adding as much value to my subscribers as possible. Enjoy!

If you're like most investors, chances are your portfolio has some degree of tech exposure. It might even be heavily tilted toward it.

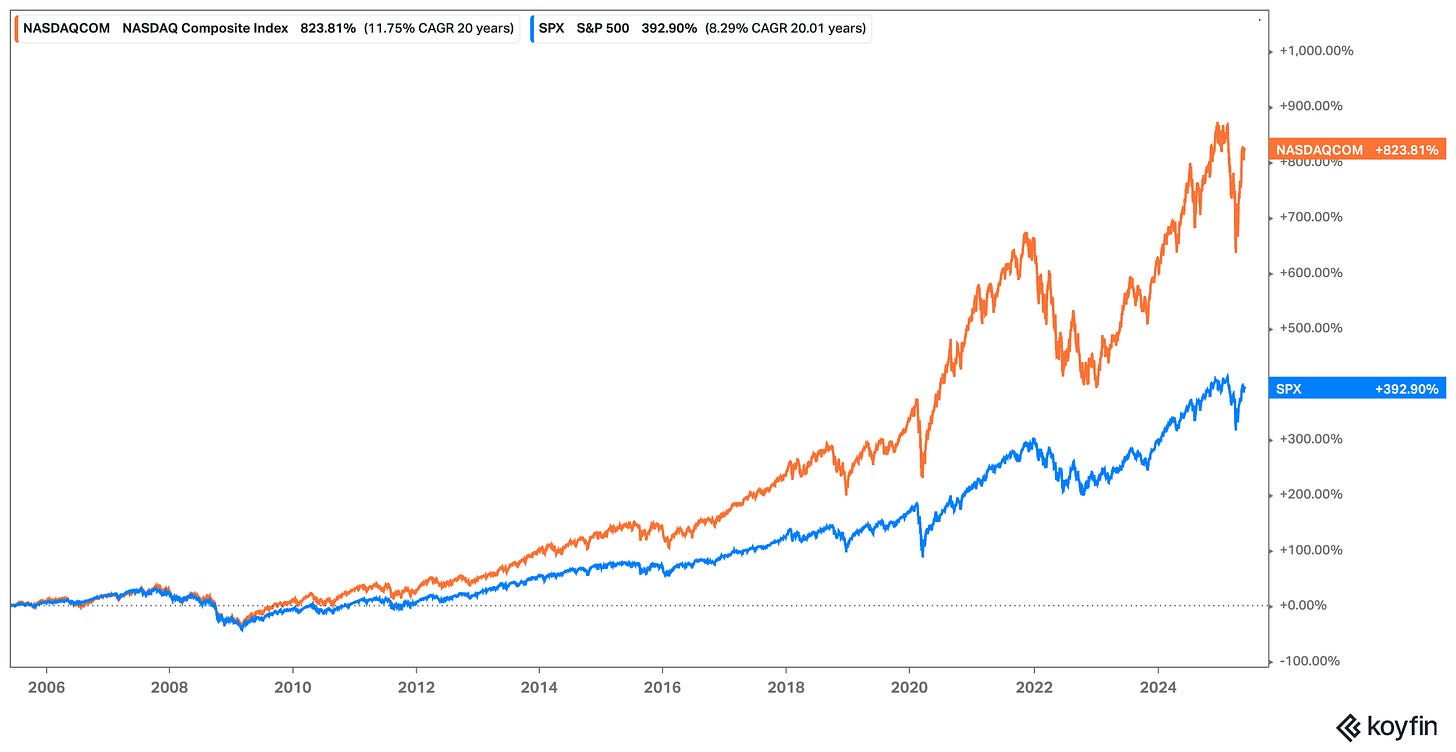

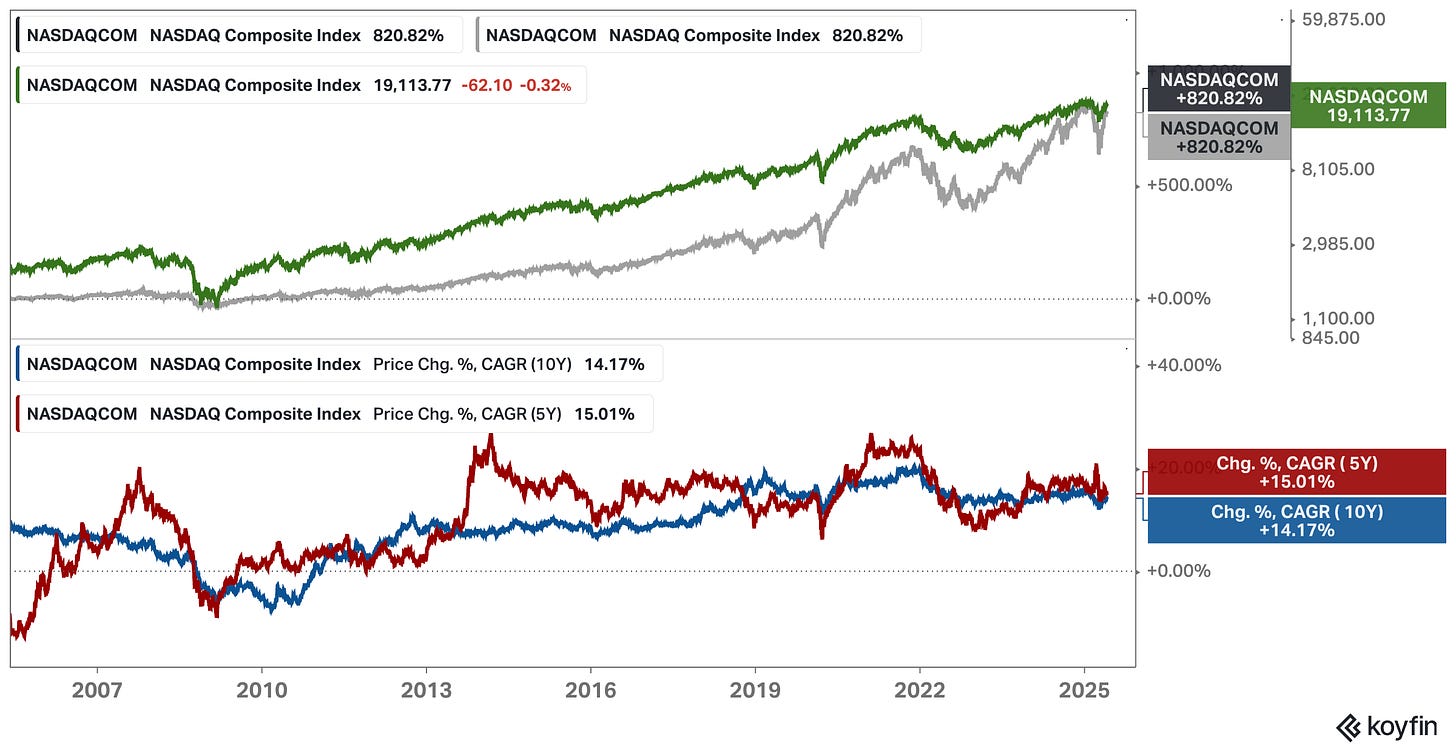

For years – maybe decades – this tilt made a lot of sense. Tech was the growth engine, the compounder, the place where network effects, sticky products, and high-margin software businesses lived. It was where you could relatively safely stretch for 20% annualized returns by just betting on the Nasdaq Composite Index and still feel like a long-term, fundamentals-driven investor.

But 2025 feels… different. More chaotic. More fragile. And maybe even more dangerous.

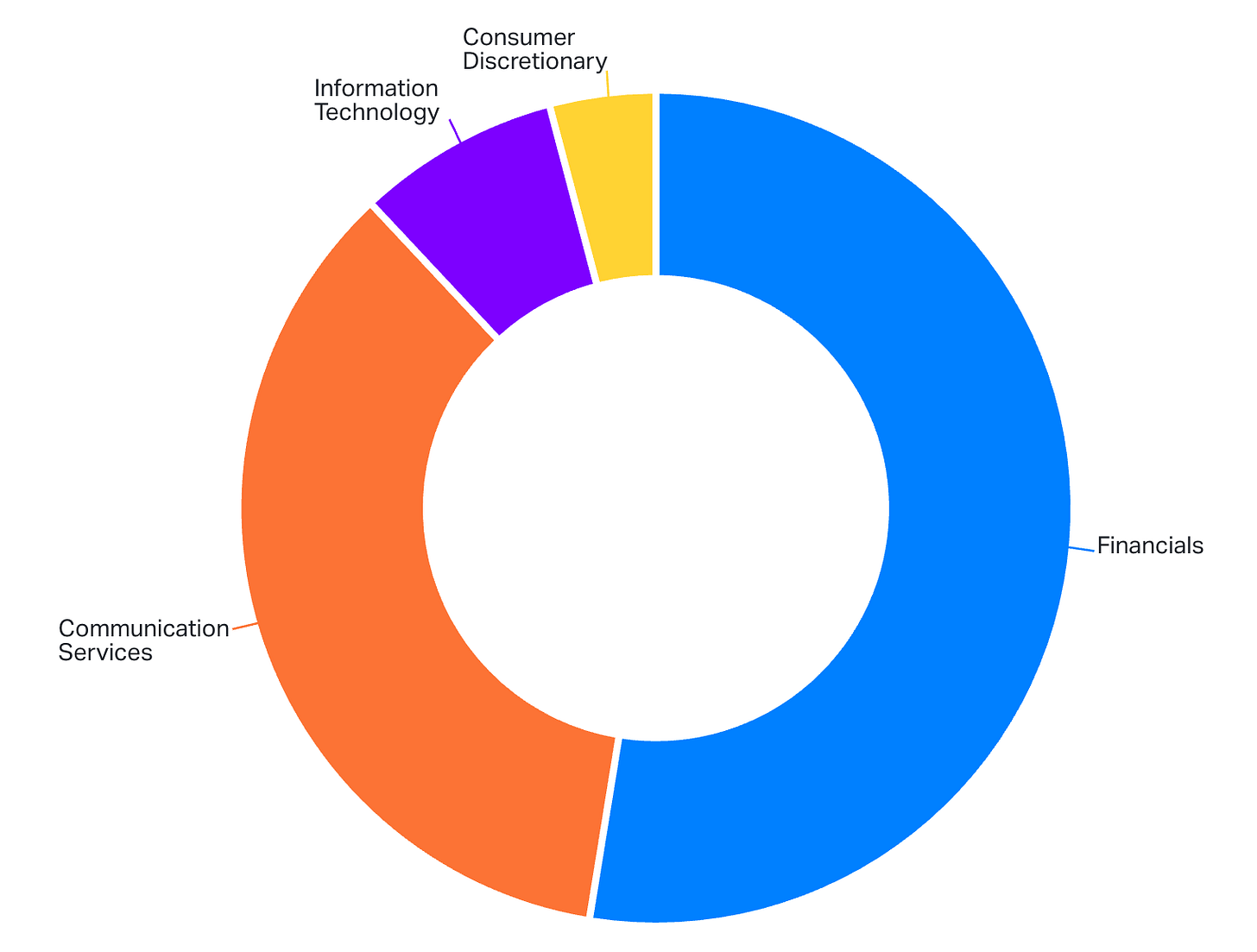

The rise of generative AI isn’t just the next big thing – it’s an earthquake, making many investors feel excited (due to potential innovative breakthroughs) and uncomfortable (due to increased uncertainty) at the same time. ChatGPT has exploded from zero to 800 million users in two and a half years, clocking over a billion searches per day. That’s faster than Google, faster than TikTok, faster than anything we've seen before.

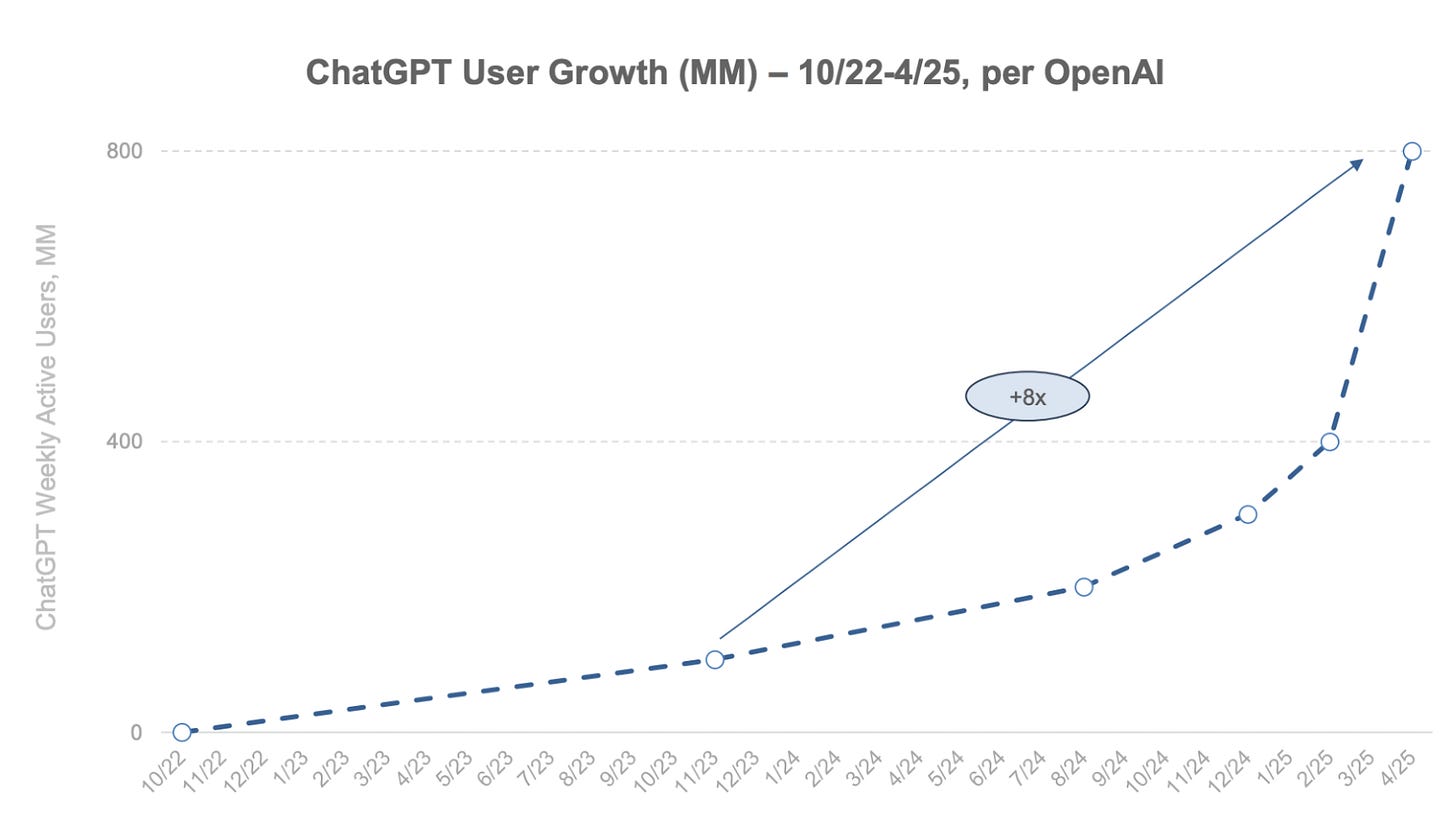

Fifty percent of S&P 500 companies now mention AI on earnings calls – a number that was close to zero just a few years ago. And yet, beneath all that excitement, there’s a gnawing sense that the tech landscape is shifting under our feet. Maybe violently.

This shift isn’t happening in a vacuum. The average lifespan of public companies in the US has been declining for decades – from above 60 years in the 1950s to 15 years today.

“The average lifespan of a US S&P 500 company used to be 67 years. Now it’s 15.“ - EY

And with AI accelerating the pace of disruption, I expect that number to keep falling – maybe even sharply? What used to take decades to play out may now happen in just a few years. Structural advantages evaporate faster. Obsolescence sets in sooner. And the margin for strategic error keeps shrinking.

My perception is that many public market investors today underestimate how AI may undermine business models that not too long ago were considered “the best business models the world has even seen.”

The irony is that we’re living through a time when tech feels both more ubiquitous but may be less defensible than ever.

Moats are shrinking. Differentiation is collapsing.

In 2022, building a new product might have required a dedicated team and a 12-month development cycle. By the late 2020s, that same product – at least in prototype or concept form – could be generated with just a few well-crafted AI prompts. The gap between idea and execution is collapsing.

The very speed at which innovation is happening – from AI generated movie productions (see video below), to AI-powered drug discovery platforms in healthcare, to humanoid robots navigating private households, to autonomous coding agents that debug and ship software with minimal human input – might be the thing that makes long-term advantage in tech investing increasingly elusive.

This blog post is about risk – not volatility, but the kind of risk that actually matters: permanent capital loss. And specifically, the new kind of risk that investors with “tech exposure” face in a world where software might be turning into a commodity, and the barriers that protected incumbents for the last 10–15 years are suddenly being breached at light speed.

I’m not sounding the alarm just for the sake of it. I’m sounding it because it might be time to step back and ask:

What are you really exposed to?

What assumptions about tech are you still clinging to that might no longer hold?

And how should we think about portfolio construction in a world where even the most entrenched players – Google, Microsoft, Amazon – are throwing tens of billions at a new technology they themselves don’t fully understand?

This post should serve as some food for thought!

Here’s what I’ll explore in this piece:

How the explosive rise of AI is compressing competitive advantages across tech

Why traditional tech moats like network effects, switching costs, and proprietary data are being eroded

Why the current moment might be more structurally dangerous than the dotcom bubble

How even Big Tech’s massive AI investments come with highly uncertain returns

The debate over whether AI is just a feature or a full-blown paradigm shift

What Mark Leonard’s take reveals about which businesses are more insulated from AI threats

Why the physical economy still matters – and might actually be a source of hidden defensibility

How to rethink tech exposure and portfolio construction for a world that’s changing faster than ever

Let’s unpack all of this.

AI Mania and the Fragility Beneath the Hype

AI is having its Cambrian explosion moment. Everyone sees it. Everyone feels it. We’re witnessing fundamental change in real time! It feels nuts – often overwhelming.

The metrics are staggering. ChatGPT’s user base has grown 8x since launch, now hitting 800 million monthly users. India – not the US – is currently the largest national user base, accounting for over 14%. Daily (!) searches via ChatGPT recently passed one billion, doing so more than five times faster than Google ever did.

In parallel, AI is dominating corporate communication. As shown above, over half of the companies in the S&P 500 now mention AI on their earnings calls – a figure that was practically nonexistent just a couple of years ago. From tech to healthcare to energy, everyone’s trying to convince investors (and perhaps themselves) that they’ve got an AI strategy.

But here’s the thing: just because a business embraces AI, this business isn’t in a defensible position. In fact, the insanely high rate of change we are witnessing – the speed with which things are changing – might be what’s making this moment so uniquely risky. Not for consumers – they’re getting better tools every day – but for businesses with “AI exposure” (whether they know it or not) and, of course, investors too, particularly those anchored in the traditional tech playbook.

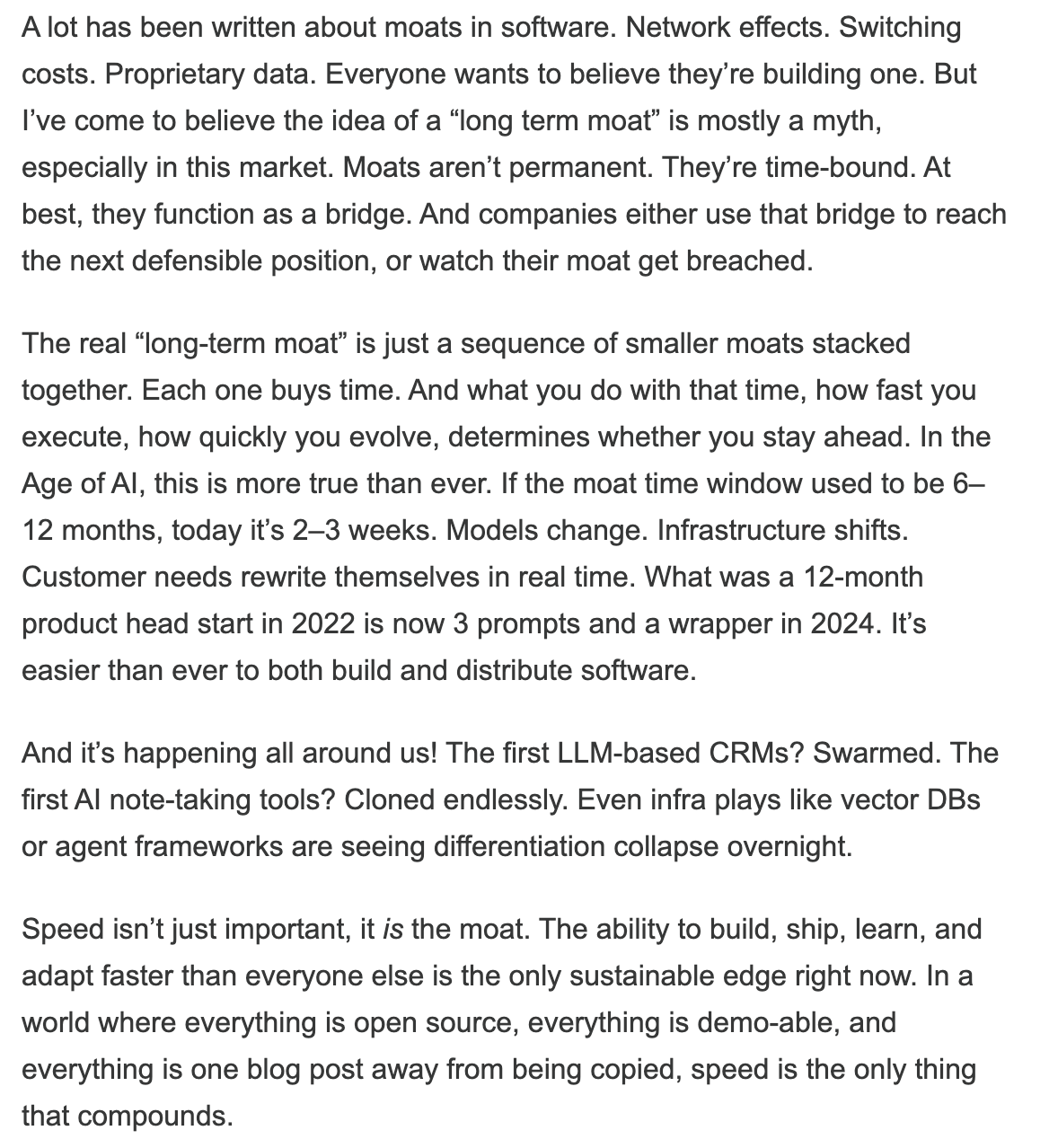

Because what AI is doing, almost invisibly, is compressing the time window in which competitive advantages matter. Features are cloned overnight. Products that once had 12-24-month leads now get replicated with a weekend hackathon. The friction to build, ship, and distribute new tools has collapsed. In some niches – CRMs, note-taking, developer tools – it’s already a free-for-all. Differentiation is vanishing at a rate that’s hard to mentally model.

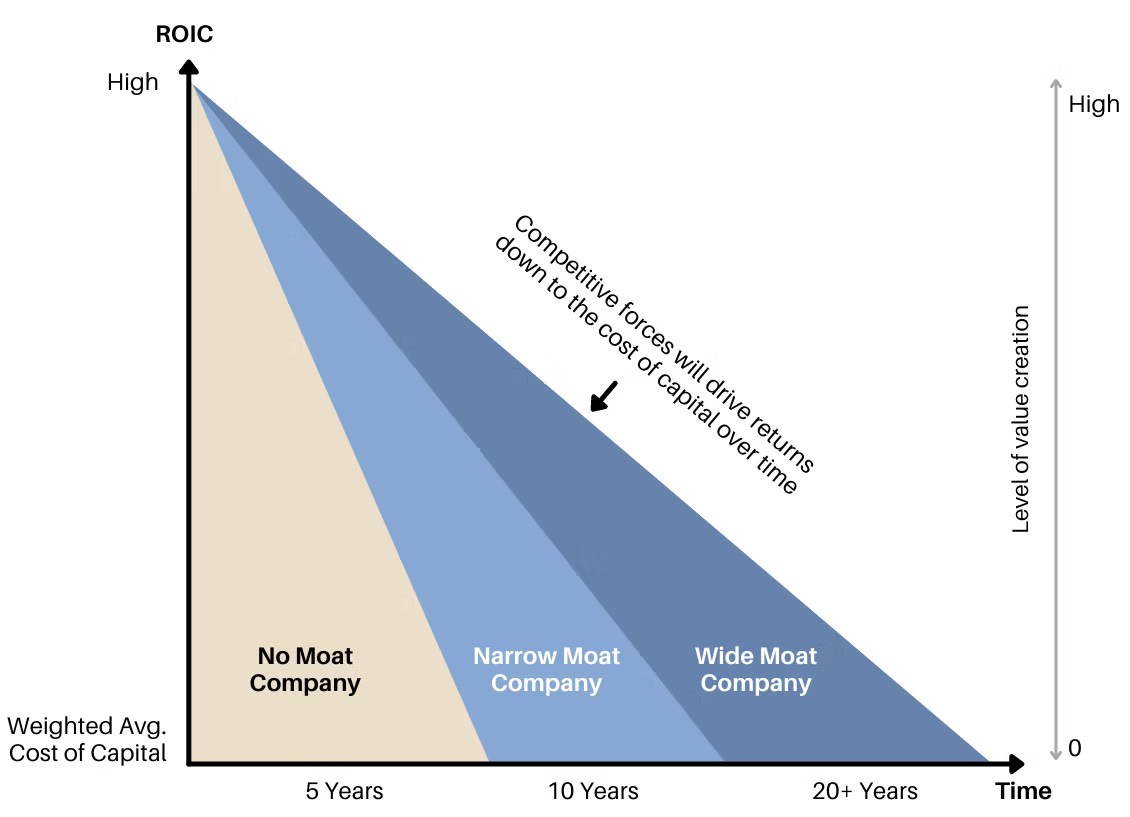

And that has real consequences for investors. Because both the magnitude and the durability of return on invested capital are what ultimately drive long-term shareholder value. That’s what moats were supposed to protect. They bought companies time – time to reinvest at high rates, time to scale without being undercut, time to defend pricing power and margins while the rest of the market played catch-up.

But if that time window is shrinking across the board, then the kind of businesses that used to be considered rare and structurally advantaged may become even rarer – or, in some industries, may not exist at all in the same form.

That’s the fragility I’m talking about. AI doesn’t just accelerate innovation – it accelerates obsolescence. And while it might be too early to say who the long-term winners and losers are, it’s not too early to acknowledge that the rules of the game are changing, fast.

It’s a strange paradox: The tech sector has never been more dynamic. Yet as investors, we may never have had less clarity about what actually endures. And without clarity, visibility, or predictability, you cannot invest (because you cannot value assets with a reasonably high degree of certainty).

Before we dive back in, a quick note…

If this post already gave you something to think about, consider this: paid subscriptions don’t just keep this blog alive – they help me produce the best-possible content I can think of. No ads, no fluff. Just high-quality, independent research for long-term thinkers. Your support helps me go deeper, write better, and serve smarter investors like you. If you value clarity in a noisy world, subscribe.

Defining “Tech” – And Why It’s Getting Complicated

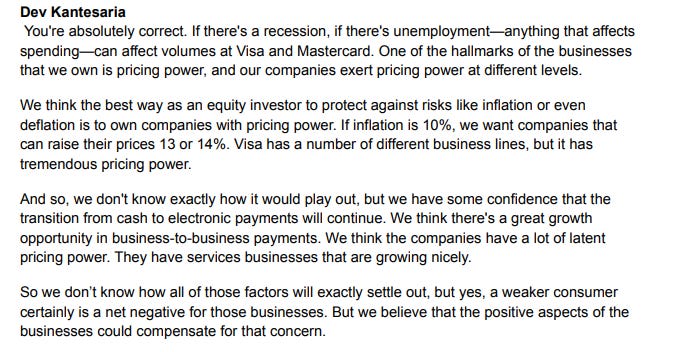

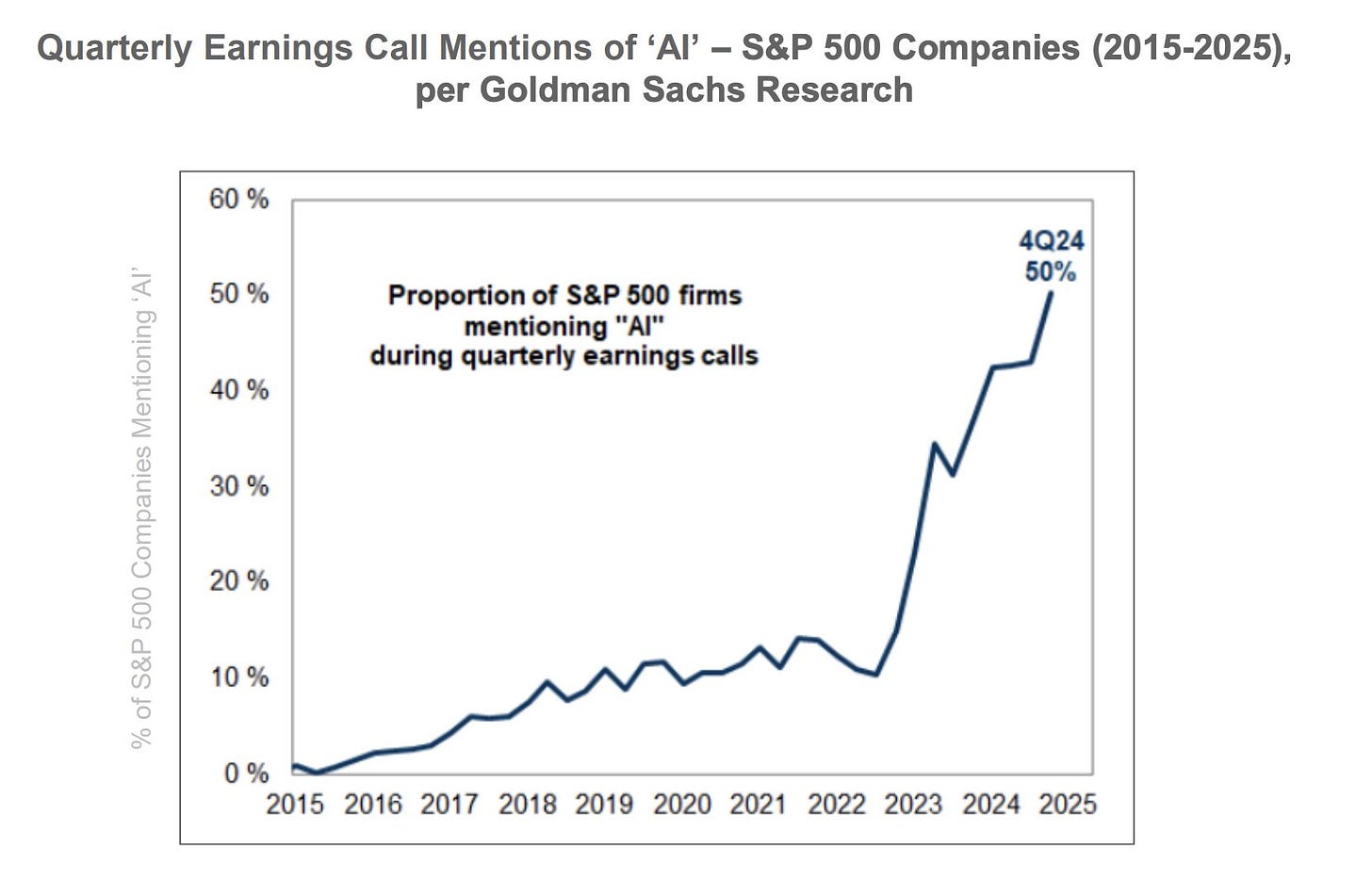

“Tech” has always been a loose label. Investors have long lumped everything from chipmakers and cloud platforms to consumer hardware and SaaS billing software into one oversized bucket. Consider my portfolio’s sector exposure shared above. Arguably, my entire portfolio consists of “tech,” but only 7.7% of my holdings are labeled as “Information Technology” companies – are Meta, IBKR, Evolution Gaming, and Wise not “tech” names? I certainly think of them as “tech.”

So arguably, the term has been more of a shorthand than a precise definition – and for a while, that ambiguity didn’t really matter. Whatever sat under the “tech” umbrella generally shared a familiar profile: scalability, high margins (or high margin potential), low incremental costs, asset-light business models, sometimes platform potential, and optionality baked into the narrative. It was less about the sector classification and more about the economics – tech was where operating leverage lived.

But in today’s AI-driven market, that old shorthand is starting to break down. The differences between so-called tech companies are becoming more important than their similarities, as the risks and pace of AI-driven disruption vary widely across business models and sectors.

Apple and Paycom aren’t facing the same threats. Amazon Web Services and a niche vertical SaaS provider don’t enjoy the same moats. NVIDIA and Salesforce may both be “tech,” but the underlying economics, risk profiles, and defensibility of their models couldn’t be further apart.

And now, generative AI is amplifying those differences. It’s pushing us to rethink what “technology exposure” even means from a portfolio perspective.

Take software. For the past decade, it was widely viewed as the holy grail of business models. Recurring revenue. High gross margins. Low incremental cost. “Software is eating the world” became gospel – and rightly so, in that era.

But what happens when software itself becomes easier to generate, easier to replicate, and, in many cases, easier to give away?

The more AI levels the playing field, the more exposed many “tech” companies become. It’s no longer enough to simply be digital, cloud-based, or subscription-driven. The market doesn’t care that your UI is slick or that you’ve got an elegant backend. If someone can prompt-engineer a clone of your product in a few days and distribute it for free or at a significantly lower price, your clients may switch and your economic castle may no longer have any form of “moat.”

This is especially true for companies operating at the shallow end of the complexity pool – low-touch SaaS tools, lightweight consumer apps, etc. These are increasingly becoming commodities. And in a world where code is free, where hosting is cheap, and where AI can write 80% of what used to take teams of developers, software as a category is losing its privileged position.

To be clear: not all tech companies are equally vulnerable. But that’s precisely the point! The broad-strokes label of “tech” is no longer useful. Investors have to go granular – to look not just at sector, but each company’s business model, at management execution speed, general product defensibility features, market structure, and how deeply embedded a company is in its customers’ workflows or supply chains (consider my Monday.com deep dive as a case study).

Monday.com: A Quiet Powerhouse in a Crowded SaaS World

When Monday.com went public in 2021, many investors dismissed it as just another project management tool competing with the likes of Asana, Smartsheet, and Trello. In a sector flooded with flashy SaaS IPOs, it was easy to overlook a company that presented itself not with bold visions of "changing the world," but with a rather modest mission: making work…

That’s where the real differentiation is now. Not in the label, but in the specifics.

Comparing Disruption Epochs: Dotcom vs AI

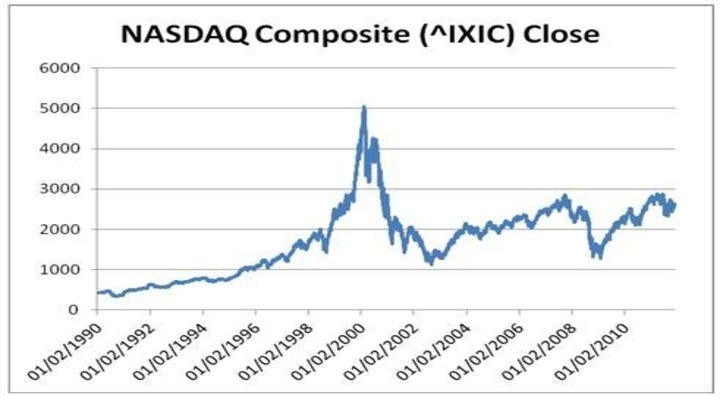

Every generation of investors faces at least one defining technological revolution. For many seasoned investors, the prospect and rise of the Internet, which resulted in the dotcom era, was the first.

It was chaotic, irrational, and – in hindsight – fairly straightforward. Companies with zero profits and barely any revenue traded at multibillion-dollar valuations. Pets.com was a punchline, and yet Cisco and Amazon were already laying the foundations for what would become truly durable franchises.

But here’s what’s important: in 2000, the real disruption risk was relatively low. The Internet was still clunky. Broadband penetration was limited. E-commerce was a novelty. Even Google was still a startup (founded in 1998). The story of the web was just beginning, businesses had time to adapt, and most of the losses investors suffered came not from obsolescence or competitive failure, but from simple overvaluation.

The ideas were right – the timing and prices were wrong.

Compare that to 2025. The AI revolution feels less like the Internet circa 1998 and more like the Internet plus cloud plus mobile – all happening at once, but on fast-forward.

The level of penetration, the speed of adoption (by both businesses and consumers), and the volume of capital flowing into the space are all orders of magnitude higher. We’re not talking about a few startups raising Series A rounds. We’re talking about trillion-dollar incumbents pouring billions into GPU clusters, model training, and full-stack integration – all at once.

And the uncertainty isn’t just about adoption curves. It’s about whether anyone can maintain an edge for long. In the early 2000s, the foundational tech players weren’t really being disrupted. In fact, companies like Microsoft and Oracle were still solidifying their dominance (again, if we leave valuation aside here).

But today? Even Google – arguably the most defensible business model of the past decade – is under siege. AI hasn’t just introduced new competition; it’s fundamentally challenged what search even is. I wrote about this here:

Google Has Been Disrupted! Now What?

In a development that has sent ripples through the tech and investment communities, Apple's Senior Vice President of Services, Eddy Cue, testified during the U.S. Department of Justice's antitrust trial against Google that searches conducted via Safari have declined for the first time in 22 years. Cue attributed this unprecedented dip to users increasingly turning to AI-powered tools like ChatGPT, Perplexity, and Anthropic's Claude for their information needs.

If we take a step back, this shift starts to resemble a true regime change. In the 2010s, following the global financial crisis, the cloud-mobile-AWS era gave birth to the greatest collection of business models the world had ever seen.

Software went from product to platform. Data turned into network effects. Subscription models led to highly valuable recurring revenues. Horowitz’s now-famous 2011 essay, Why Software Is Eating the World, wasn’t just an observation – it was a prophecy that played out over a decade of monster returns, particularly in the Nasdaq. Back in late 2021, the 10-year compounded price return of the Nasdaq Composite was >20%!

But here in 2025, we may be seeing that cycle turn? I don’t know. Of course, I don’t know. No one does. I’m just thinking out loud.

Again, view this post as some food for thought, and keep in mind that I arguably own only “tech” names and have no intention of selling them.

But one hypothesis is that “software is NO LONGER eating the world.” It’s being digested, reconstituted, and in some cases, commoditized by AI.

The returns of the past were driven by new forms of leverage: global scale, high gross margins, and resulting operating leverage dynamics, automation, code, high switching costs, and (global) network effects.

In a future world of cheap AI agents, those levers are seemingly more accessible; not all of them, and certain companies possess multiple moats, making them more defensible, but ultimately, I expect more and faster disruption going forward.

That’s the difference. Dotcom was a hype bubble. This? This might be something much deeper, a more structural change, possibly changing the world of work AND the “clue of societies” forever.

Moats Aren’t What They Used to Be – Especially the Tech-Enabled Ones

If you’ve invested in tech over the past decade, chances are the word moat has played a central role in your thesis. Recurring revenue, high switching costs, network effects, proprietary data, distribution advantages, brand – the tech sector gave us a masterclass in how software could embed itself into the daily life of both consumers and businesses. You didn’t just buy a product. You often got locked into an ecosystem, you often subscribed to a service and paid businesses upfront (creating negative working capital dynamics, essentially funding the company’s growth), you accepted price hikes without much churn, your usage generated data that improved the product for everyone, and your entire workflow or tech stack increasingly depended on integrations with that single vendor.

But that playbook might be showing serious cracks in the age of AI. AI is coming for you, tech companies … Better watch out!

The core issue is this: most tech moats were built on friction – on the assumption that it’s hard to build (talent was scarce), even harder to scale, often hard to switch, and taking all of this together … hard to replicate.

AI is now actively erasing all three.

Consider network effects – long hailed as one of the strongest forms of competitive advantage in tech. AI is putting pressure on some network effect types (on some more than others). In lightweight, tool-based products – think early note-taking apps or LLM-based CRMs – the “network” often consists of usage data, shared templates, or open communities. These are relatively shallow and easy to replicate. When dozens of alternatives pop up overnight with similar capabilities, more attractive UIs, agents trained to create the best-possible marketing campaign (at virtually no cost), trained on broadly available datasets, the switching costs are minimal. Familiarity is high. Loyalty is low. And differentiation fades fast.

But that’s not true of all network effects. Products with direct user-to-user interactions, like Instagram or WhatsApp, are, I believe, far more defensible. Their value grows exponentially with each additional user because of the actual connections, not just the usage data. Same for marketplaces like Airbnb or platforms like YouTube, where liquidity or content density becomes self-reinforcing. These kinds of networks don’t unravel easily. But once an unraveling process starts, it often picks up pace quickly!

What AI seems to threaten most are the weaker, data-driven network effects – the kind that sounded good in a pitch deck but never built true user interdependence. In those cases, the speed and replicability of AI might compress the edge down to months, not years.

Switching costs? Many SaaS companies have spent years cultivating these – think CRM systems, HR platforms, financial reporting tools. But in a world where generative AI relies on robust datasets, can auto-translate interfaces, port data, and customize workflows with natural language, switching is no longer the pain it used to be.

A good chunk of “stickiness” might have been just legacy UX inertia – and that’s starting to disappear.

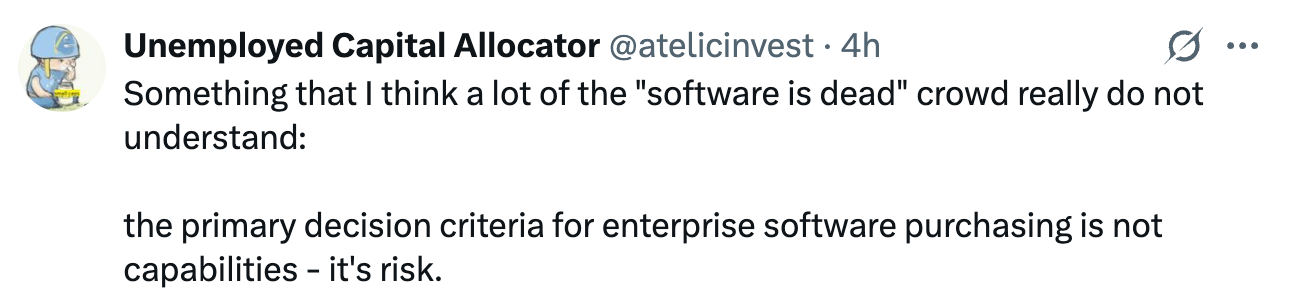

The counterargument would be that many companies are moving slowly and are reluctant to switch. Distribution and trust also play critical roles. For now, at least, the "risk" of switching may still seem too high.

So, there’s nuance. Not all businesses are equally vulnerable.

Mark Leonard, at the 2025 Constellation Software AGM, made a sharp distinction between pure software products and software+services bundles. He suggested that AI is far more disruptive to companies that are low-touch, standardized, and run purely through the web. But in industries where software is deeply embedded in workflows (consider Computer Modelling Group as an example) – and combined with services, training, and customization – AI may become an enhancer, not a threat.

“Where it is more of a threat or more of an opportunity depends to some extent on the kind of business you're talking about. So if you're talking about a SaaS business with very few people with software that is sold through the Internet that has very little training, very little support, that isn't automated, then I would think AI would be a pretty significant threat. The other end of the spectrum, and Dexter gave the example of pulp and paper is where we deploy a solution that looks like an awful lot of people who spent an awful lot of time around pulp and paper and software. So we're providing advice, support, customization, integration and intimate knowledge of the pulp and paper industry. And so at that end of the spectrum where it's a bundle of services and software, I think AI is much less of a threat and much more of an opportunity where we can deliver what we're learning about AI to our end customers.“ – Mark Leonard

That’s a critical insight. AI doesn’t destroy all moats. It just forces a re-evaluation of where the value really lives. If your edge is code and interface, you’re exposed. If your edge is deep domain expertise, integration, or customer intimacy, you might actually be able to use AI to strengthen your advantage.

But even that comes with a caveat: you have to move fast. Because, as explained, the window of defensibility is shrinking, and the slope of change is steep.

Even proprietary data, once considered a very defensible moat, is facing real challenges. Models are becoming good enough with generalized datasets. And for many applications, the marginal advantage of a unique data asset isn’t enough to outweigh the cost and effort of managing it. If a competitor starts coming along, providing a similar value proposition at 5% of the current cost, managers might think about this offer twice.

On top of this, the rise of AI may bring along a completely new major computing platform, making “apps” as we know them largely redundant. Such a transition to a new computing platform (AR glasses) may also challenge the more defensible network effects mentioned above, as social media apps, for instance, will have to reinvest themselves to feel “natural” on the new platform. But arguably, this shift, I believe, is first and foremost a major threat to mobile apps and software run on desktops.

To quote from my Monday.com deep dive:

Let’s address the elephant in the room when assessing various risk scenarios related to Monday:

How Real Is the AI Risk to Monday.com?

One of the more unsettling long-term risks for Monday.com – and frankly for many SaaS platforms, or more broadly, virtually every software company across the globe – comes not from a traditional competitor, but from a fundamental shift in how we interact with technology.

As generative AI accelerates, the very concept of using "apps" could become outdated.

Meta’s CTO Andrew Bosworth recently outlined a provocative thesis: in a world where users simply express intentions in natural language, the app layer disappears. You won’t open a calendar app to schedule a meeting or a CRM to update a sales lead – you’ll just tell your AI assistant what you want, and it will coordinate all the necessary actions behind the scenes.“

That’s not just a UI redesign. That’s a redefinition of computing.

OpenAI, with its plans for agent-based operating systems, is already nudging in this direction. The endgame? A computing paradigm where the OS, apps, and interfaces dissolve into one seamless AI-native layer.

If that vision plays out, Monday.com could face an existential threat. After all, it’s a visually structured, user-driven platform. Teams log in, click through boards, customize workflows, and manually assign tasks. In a world where natural language is the interface and agents handle execution, the entire idea of logging into a dashboard might seem archaic.

The effect of all this is a massive moat compression across large swaths of the software and tech-enabled landscape. Time itself is contracting. What used to be a multi-year advantage might now last just for a few more months, maybe 1-2 years.

The pace at which AI is progressing is hard to fathom and businesses have to adapt by moving fast. The “move fast and break things”-motto, coined by Mark Zuckerberg, needs to be embraced by all businesses.

So, as Jamin Ball put it in his piece “Clouded Judgement 5.30.25 - Moats in the Age of AI”:

“Speed isn’t just important, it is the moat.“

In today’s environment, being able to execute fast, ship fast, learn fast, and adapt faster than your peers might be the only edge left?

That doesn’t mean all moats are dead. But the durable, “tech-enabled” moats that defined the 2010s – many of them are now time-bound bridges (to stick with Jamin’s analogy above). Temporary. Situational. And unless companies can use that time to leap to a new defensible position, they’re just standing on a bridge waiting to be overrun. That’s why I’m still bullish on Meta – Zuck just gets things done fast – he still does –, never tired, always hungry.

Ironically, many of the most defensible business models now might be those with non-tech moats layered with tech – think vertical integration, tech + heavy infrastructure plays, domain expertise, regulatory complexity, or high-touch services enhanced by software. These don’t scale as fast, scaling them may be capital intensive, but they’re much harder to disrupt (quickly).

AI hasn’t killed moats. But it has changed where they live.

Portfolio Risk Reconsidered – Fund Managers vs Private Investors

Risk means different things to different investors.

For private investors like you and me, risk should primarily be just about permanent capital loss. Period.

Does the company have low debt levels or could leverage kill the business if it hits a rough patch? Can this business defend its economics and continue to grow and earn above-average (or at least above cost of capital) returns on capital over time? Or can competitors eat their lunch, and one might see operating leverage effects in reverse?

Those are the kind of questions long-term investors should obsess over – and rightly so. The stomach for short-term volatility is what buys us entry into those long-duration compounding stories.

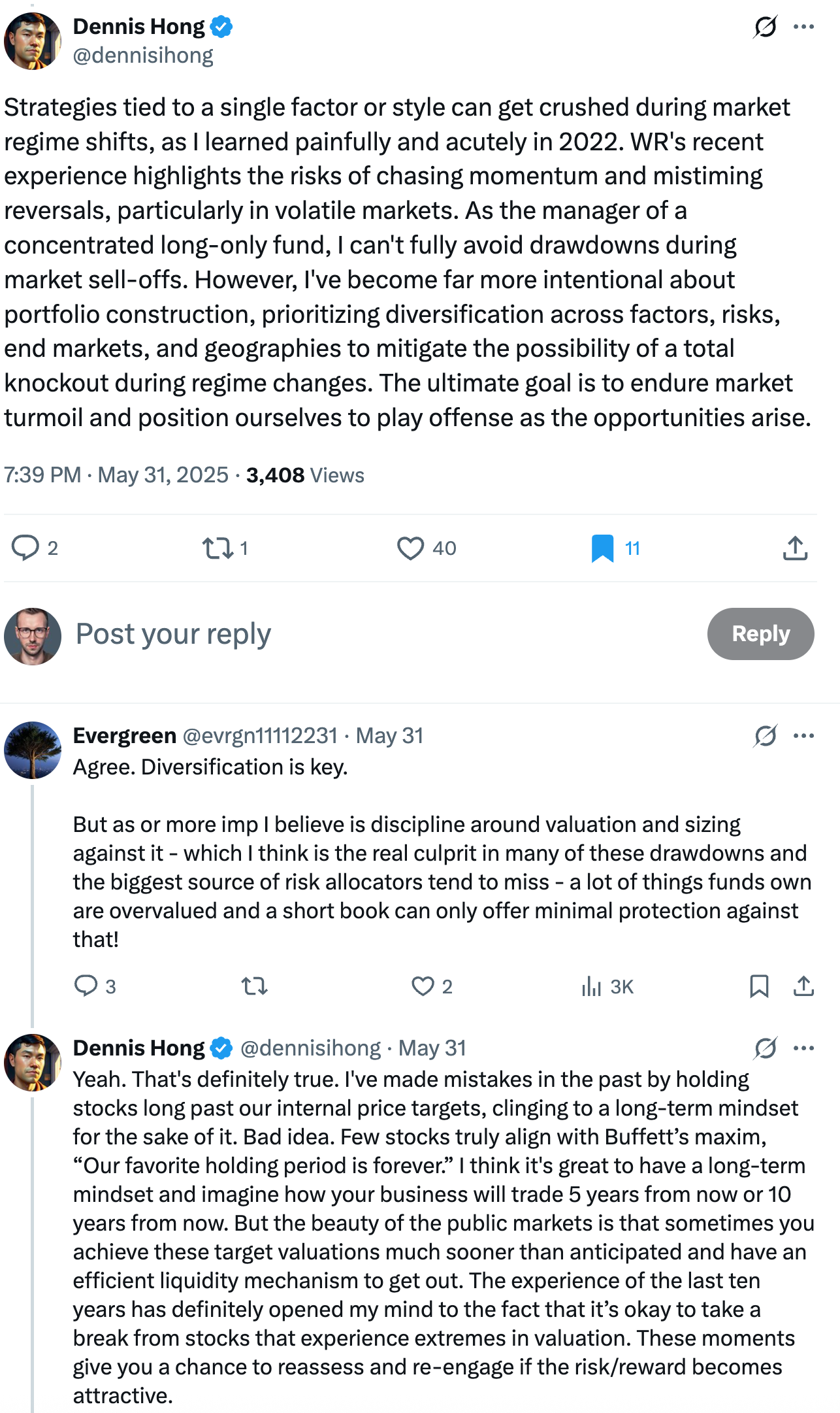

But for fund managers, particularly those managing other people’s money, risk (often) takes on a more complex shape. Volatility itself becomes dangerous – not because it affects intrinsic value, but because it affects their investors’ behavior and how much trust they continue to place in their money managers. Clients pull capital. Allocators lose confidence. Public performance rankings shift. You’re not just fighting market cycles – you’re fighting redemptions and narrative whiplash.

Just think of what happened during the 2022 tech drawdown. Rob Vinall, one of the most thoughtful long-term managers out there, saw brutal drawdowns as tech & “growth” multiples compressed across the board. He had the benefit of a like-minded investor base – people who understood the process and stuck with him, and he luckily quickly recovered temporary paper losses (the chart below is cropped off in 2022 to illustrate how rough the drawdown was; but now, Rob is back to new ATHs!). But many others weren’t so lucky. And the pressure to de-risk or rotate out of positions just to placate skittish investors can push managers into decisions that have nothing to do with business fundamentals.

That’s where AI complicates things even further. For professional investors, AI-induced volatility isn’t just market noise – it may represent a career risk. Take Dennis Hong’s recent post on Japanese software companies. His enthusiasm was evident, but so was his hesitation. He laid out the multi-layered risks of investing in unfamiliar markets with structural and cultural headwinds – not just valuation risk, but liquidity, currency, alignment, and exit risk. And that was before even layering on the uncertainty of how AI might impact those companies’ moats.

For individual investors, those same dynamics matter a little less. We don’t need to worry about quarterly redemption notices. But we do need to worry about something even harder to model: structural disruption. AI might not tank a stock tomorrow, but it could fundamentally erode a business’s economics over a multi-year period (or, as outlined, sometimes the disruption may happen in a matter of months) – especially if we’re anchoring to the same frameworks that worked in the last cycle.

“The worst thing one can do, especially late in a paradigm, is to build one’s portfolio based on what would have worked well over the prior 10 years, yet that’s typical.” – Ray Dalio

The real challenge is that most portfolio construction still assumes some level of continuity. But what if tech, as we know/knew it, is becoming a structurally worse place to invest – not because the products are worse, but because the economics and visibility are? What if the risk is not a 30% drawdown, but owning companies whose moats evaporate before our thesis has time to play out?

Volatility is survivable. Fragility isn’t.

Big Tech’s Uncertain Bets and the Limits of Scale

If anyone should be well-positioned to dominate the AI age, it’s the tech giants. Apple, Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Meta, NVIDIA – these companies have the scale, the talent, the data, and the distribution. And yet, when you zoom out, the picture gets murkier – not clearer.

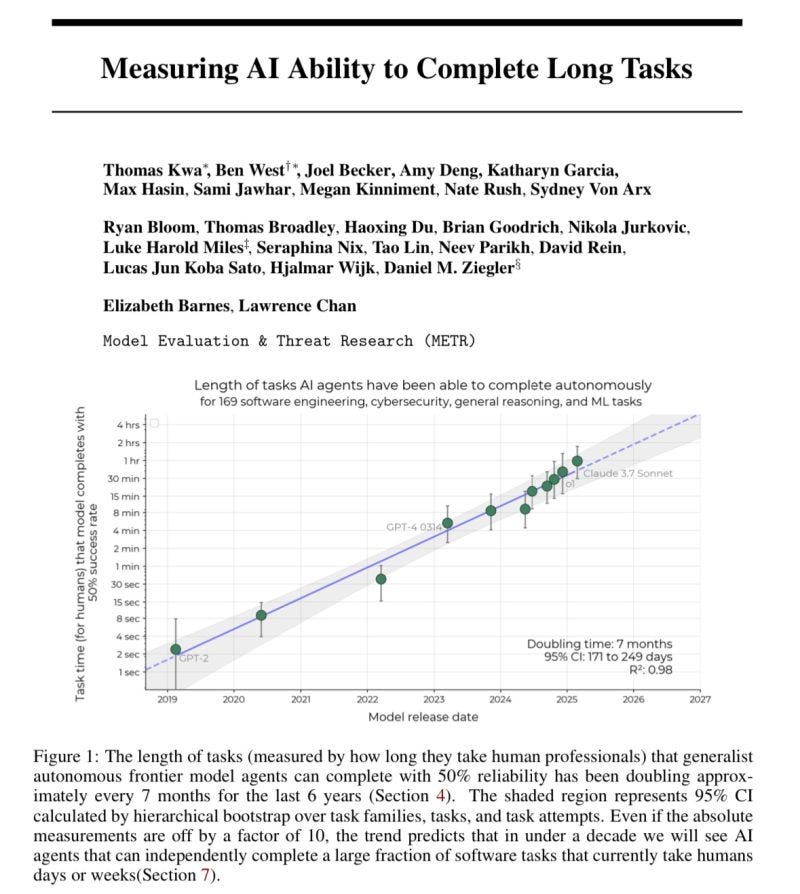

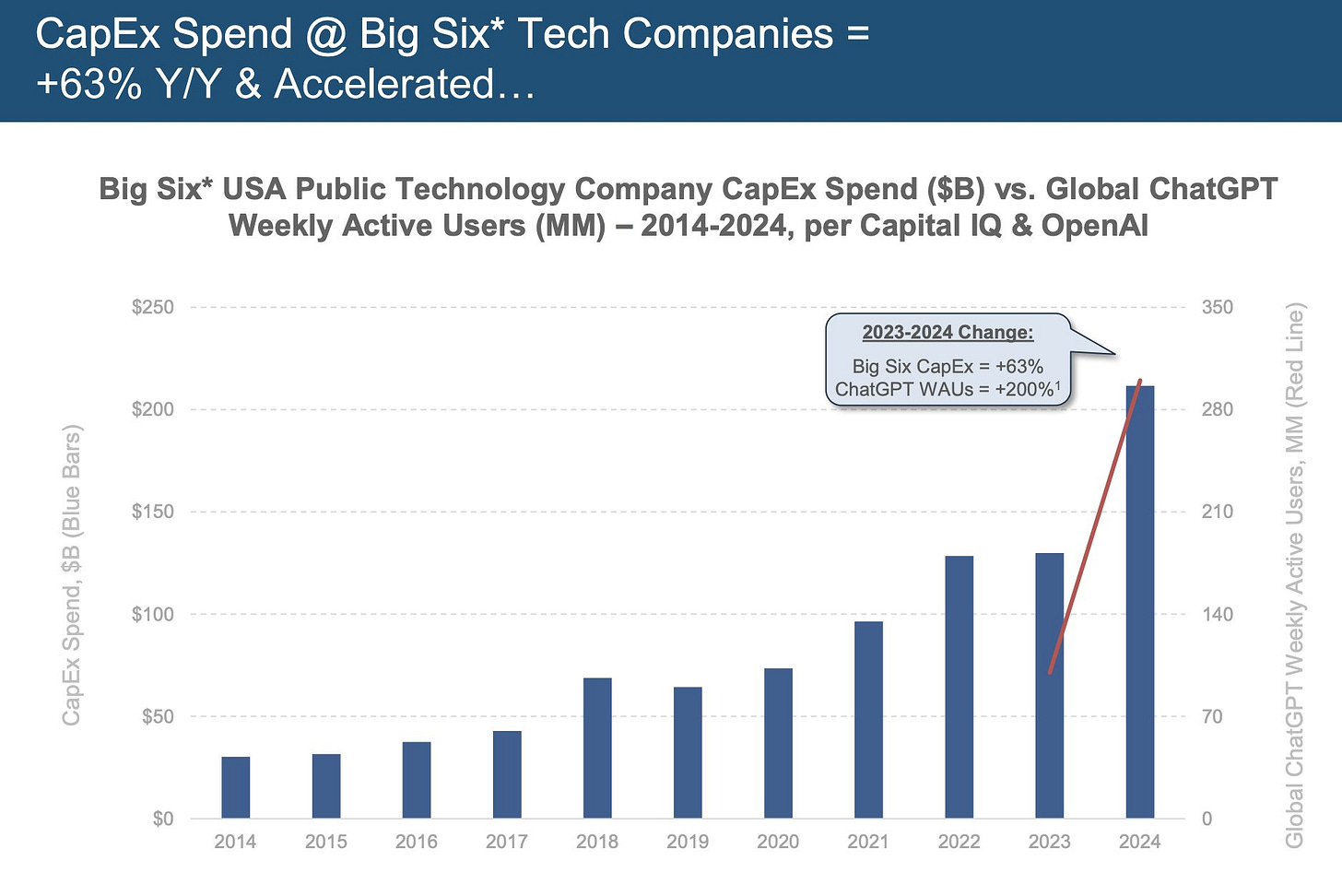

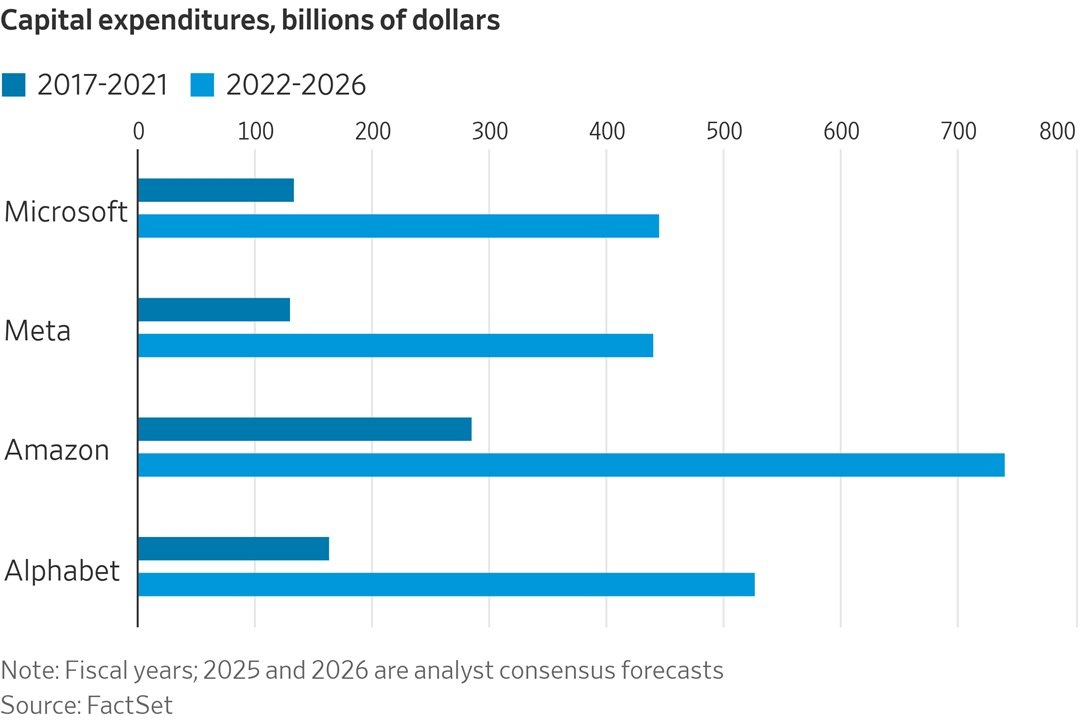

The numbers are staggering. In 2024, the Big Six increased CapEx by 63% year-over-year, committing more than $212 billion. That’s not a typo. It’s one of the largest capital spending booms in tech history.

Here’s another whopping statistic I came across: "Between 2022 and 2026, [hyperscalers] will have made a whopping $1.14 trillion in capital expenditures, or three times what they did in the preceding five years."

But here’s the kicker: no one knows what the return on that capital will be. Not even the companies themselves.

And that’s the problem.

When the largest and most sophisticated businesses in the world all pile into the same space, competing on the same axis (compute, model quality, distribution), it might a zero-sum arms race.

What feels like reinvestment might end up being overinvestment.

What sounds like a “moat-expanding initiative” might be a desperation move to stay relevant.

Google is the clearest example. For over a decade, it was widely regarded as the best business on the planet. A distribution monopoly with a 50% margin, cash-minting search engine, and an ad machine that scaled like magic. But now? AI has put its core product – search – directly in the crosshairs. Googling is replaced by ChatGPTing – especially among younger demographics. All of a sudden, the thing that looked like an impenetrable fortress is being poked at from every angle. Not because competitors have better branding or lower prices – but because AI has fundamentally changed what users want (instant answers to search results or entirely new, more creative queries).

Investors should pay close attention here. The rise of AI has triggered massive reinvestment – but to come back to the concept we brought up earlier in the post, the magnitude and durability of returns of those reinvestments is anything but clear – even for Big Tech.

High ROICs aren’t guaranteed. And short-term high ROICs alone aren’t enough. They have to be durable to be valuable. And it’s precisely that combination – longevity and (seemingly infinite) reinvestment opportunities – that powered tech’s dominance during the 2010s.

This wouldn’t be quite as concerning if valuations were pricing in uncertainty. But they’re not (Google’s the exception here). As of 2025, the IT sector is trading in the 82nd percentile of its absolute price-to-earnings ratio over the last decade – and in the 76th percentile over the past 30 years.

In other words, we’re paying near-peak prices for businesses facing peak uncertainty.

That’s a tough setup. Especially in a sector where capital intensity is surging, moats are compressing, and reinvestment returns are increasingly hard to forecast.

But today, those pillars are wobbling. If you're investing in a business that reinvests 50% of its profits at 20% ROIC (resulting in 10% growth), but the durability of that return profile is questionable beyond a few quarters… what exactly are you underwriting? What price can you pay for that asset?

This is also where Buffett’s allergy to tech starts to make more sense. It’s not that he doesn’t understand the internet or software. It’s that he doesn’t trust what he can’t see – and right now, the long-term economics of AI are almost impossible to forecast. When the landscape is this unpredictable, even great execution might not deliver great outcomes.

To be clear, these giants aren’t going away. They’ll likely continue to grow. But growth is not the same as value creation. Especially not when massive spend is being funneled into hyper-competitive, fast-shifting areas where edge collapses quickly and regulation hasn’t even caught up.

This might not be the end of Big Tech. But it could be the end of Big Tech as we knew it.

Is AI Just a Feature? Or a Paradigm Shift?

One of the most important – and underappreciated – debates in investing right now is whether AI is a true paradigm shift or simply a powerful new feature that existing platforms will absorb – a feature that will arguably make them better, stickier, (much) more profitable.

For instance, Microsoft just laid off 3% of its workforce, seemingly because AI can replace many of the jobs formerly completed by humans.

Your answer to that question has massive implications for how you build a portfolio, value companies, and assess risk.

Some argue that AI is just another layer – like mobile, like cloud. They believe it will enhance existing products, improve margins, streamline workflows. In this view, the winners are already picked. Microsoft, Meta, Google, Amazon – they own the users, the data, and the compute. AI is simply the next thing they bolt on.

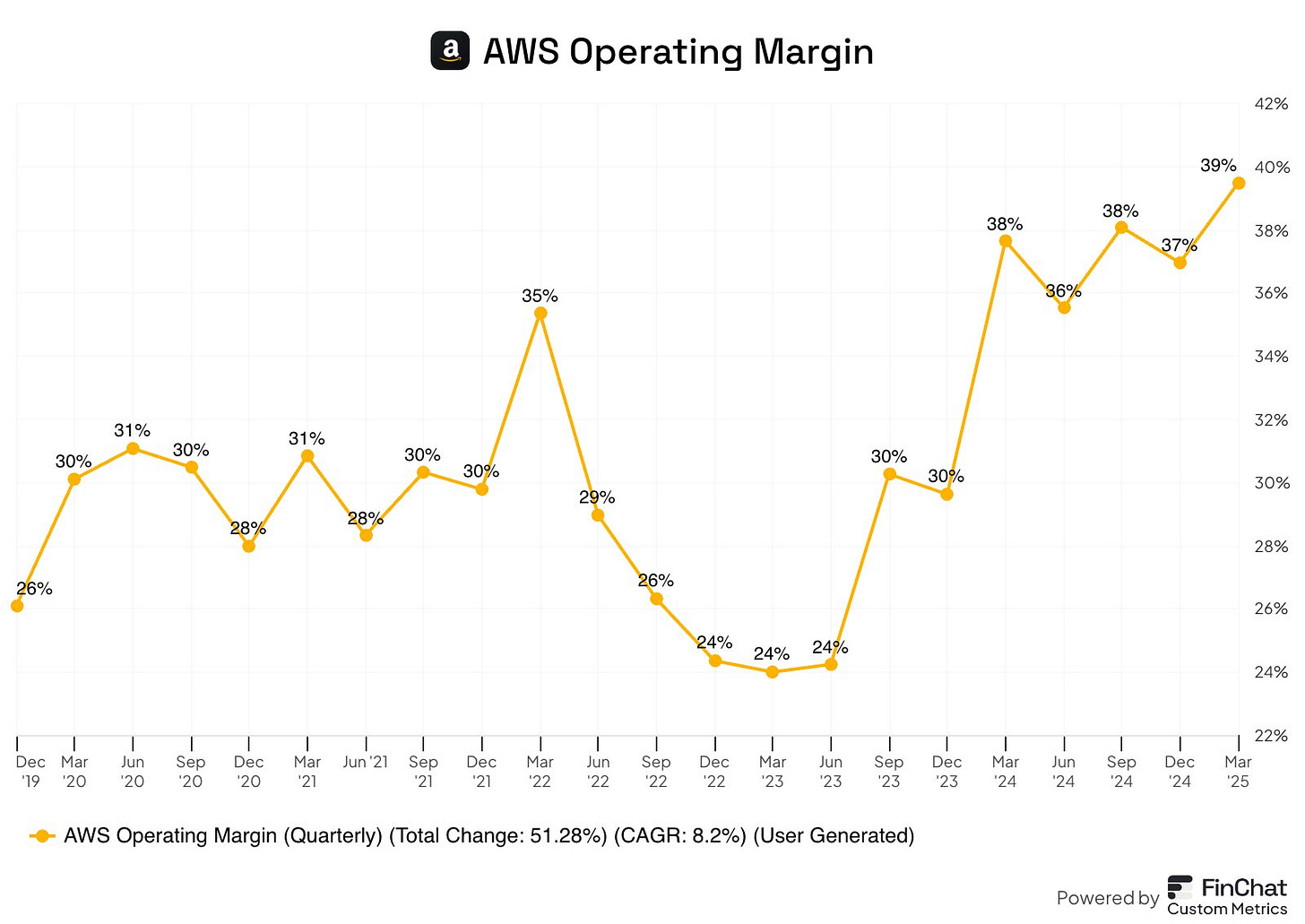

And the hyperscalers will keep fueling the boom from the infrastructure layer – selling the picks and shovels, and watching their cloud businesses become more profitable every quarter. Easy mode.

The value accrues to scale and distribution. End of story.

But I don’t think it’s that simple. It’s not that I strongly disagree – I really don’t know, and I do own Meta (which says something as well) –, but I think your assessment requires a lot of nuance.

So the alternative view – the one I find more compelling, at least for now – is that AI is a paradigmatic change. Not just because of what it does, but because of how it erodes value. It accelerates commoditization. It collapses differentiation in many ways. It dramatically lowers the cost of replication. And it breaks many of the levers incumbents – and now I’m talking about “Tech” in general and not “Big Tech” exclusively – relied on to maintain dominance: product moats, organizational inertia, even talent.

We’ve already seen it play out in niche verticals. The first LLM-based CRMs, note-taking tools, code assistants – all of them were cloned within weeks. The tools that initially felt groundbreaking quickly became interchangeable. The winners weren’t necessarily those with the best product. They were the ones who could ship faster, adapt quicker, and build more efficiently. In a world where everything is open source and one blog post away from being copied, speed is no longer a tactic – it’s the moat.

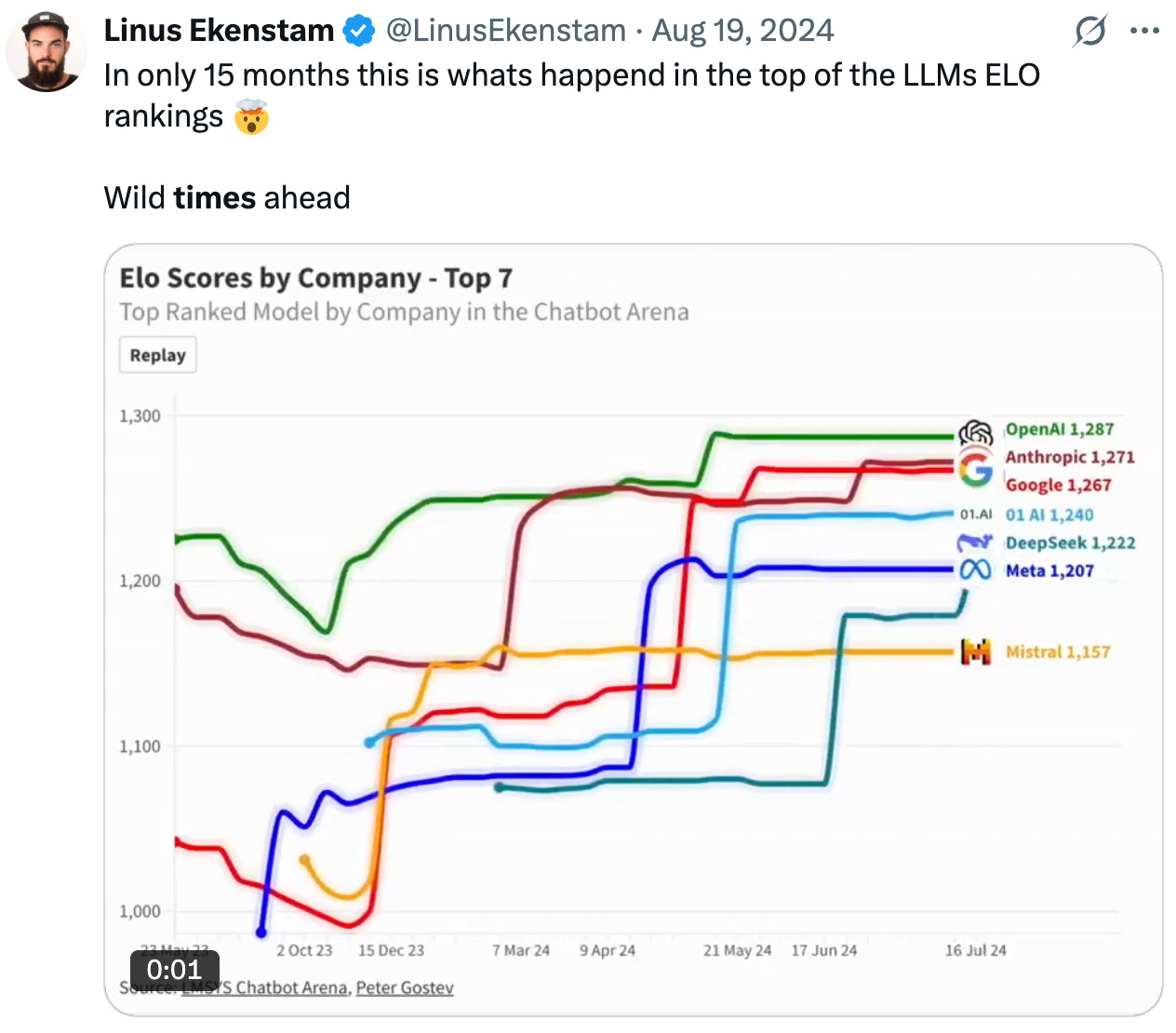

And again, I cannot emphasize this enough, things are moving incredibly fast. Blink and you might miss the next top-ranked LLM model.

Eric Schmidt recently predicted (watch it here) that within a few years, we’ll have “AI mathematicians” and “super-programmers” – agents that can independently experiment, test, and refine ideas millions of times faster than any human. If he’s even halfway right, software becomes scale-free. The entire product development loop – from idea to deployment – gets compressed into minutes.

What does that mean for software companies built on slow iteration cycles? I don’t know. But that’s just one tiny domain Eric Schmidt’s prediction will affect.

Its implications are far-reaching and touch on everything: education, medicine, finance, law, logistics, agriculture, energy, defense, cybersecurity, entertainment, gaming, architecture, climate, biotech, retail, customer service, journalism, governance, scientific research, therapy, translation, music, insurance, ethics, recruiting, negotiation, testing, and diplomacy.

Contemplating its scope is akin to contemplating the scope of the universe – fascinating, terrifying, and deeply unsettling all at once because our tiny human brains were never built to grasp something so vast and recursive, so far beyond our intuitive sense of scale and time.

And if AI really is a paradigm shift – not just for tech companies but for entire economies and for societies – then we’re likely heading into uncharted territory in more ways than one. Imagine a world where AI drives annual GDP growth of 10%, yet unemployment climbs to 10% or even 20%. That’s not science fiction. That’s a plausible near-future scenario. As Marc Andreessen recently put it, “AI will make everything so cheap, it’ll break the economy.” Productivity may explode, but labor displacement could outpace our social, political, and economic systems’ ability to adapt.

Investors often model cash flows – few model second-order effects on labor markets, policy responses, or societal volatility. But they matter. Because if AI breaks how value is distributed, it may also break how it's captured.

The Physical Economy Still Exists

It’s easy to get swept up in the speed and spectacle of what’s happening in tech right now. AI is captivating. It’s intellectually thrilling. And it genuinely feels like the start of something epoch-defining.

But while everyone’s busy re-engineering the future in Python and GPU clusters, it’s worth remembering a simple truth: we still live in a physical world. Mark Zuckerberg’s metaverse vision still seems quite far off.

Buildings still need to be built. Water still has to be pumped. Crops still have to be harvested, transported, processed, and sold. Industrial supply chains still exist. Healthcare still relies on physical diagnostics, drug manufacturing, and trained practitioners. Food, energy, shelter, logistics – none of it gets magically replaced by a chatbot.

That doesn’t mean AI can’t or won’t enhance parts of the real economy. It already is. Take Munich-based startup Fernride, for instance. They're revolutionizing logistics by deploying autonomous electric trucks in industrial yards and ports, utilizing a "human-assisted autonomy" model where remote operators oversee multiple vehicles, ensuring both efficiency and safety. This approach not only addresses the critical driver shortage but also enhances sustainability and productivity in logistics operations.

And that’s just one very unique example. Then there’s predictive maintenance, robotic process automation, etc. – there’s huge potential here.

But the keyword is enhance, not replace. Most of these industries are not pure code. They are complex hybrids of physical infrastructure, regulation, human labor, and legacy systems. AI will change how they operate – but it’s not going to collapse their value the way it might for some software niches.

And yet, if you look at most investor portfolios – especially those with a “quality” bias – they’re still overweight tech. The assumption has long been that the best businesses live in software. Maybe that was true in 2015. Maybe even in 2020. But in 2025, that assumption needs to be re-examined.

Because here’s the irony: the same AI revolution that’s threatening software moats might actually amplify the value of the defensibility of high-quality businesses in the real economy. Especially those that are hard to digitize, hard to copy, and deeply embedded in the physical world. These companies don’t move as fast – but they don’t break as easily either.

There are businesses out there producing predictable cash flows, with strong balance sheets, conservative management, and competitive positions that have lasted for decades. If you haven’t heard of the Lindy effect, go ahead and open Google (or I bet, many of you will use a chatbot ;-)) to learn more about this mental model!

Many of them aren’t flashy. They don’t get X threads written about them. But they might be exactly the kind of ballast investors need as tech volatility ramps up.

It’s not about abandoning innovation or ignoring the potential of AI. It’s about acknowledging that there’s a world beyond tech – and in a market obsessed with speed, efficiency, and disruption, slower-moving industries might offer a very different kind of edge: durability. That’s what Buffett has always preferred and why he “missed” the tech run.

Conclusion: Build Like It’s 2025, Not 2015

So, are we living through the most risky time for tech investors in modern history?

I think the answer is yes – but not for the reasons that usually dominate headlines.

It’s not just valuations, though those are lofty. It’s not just competitive pressure, though that’s real. It’s the deeper, structural shift in what creates – and sustains – advantage in a world where technology moves faster than business models can adapt. AI isn’t just changing the playing field. It’s shortening the game clock.

What made tech great in the past may not make it great going forward. Many of the moats we once considered enduring – network effects, switching costs, proprietary data – are being compressed, cloned, and commoditized. Meanwhile, the giants of the industry are engaged in a furious, capital-intensive arms race, the outcome of which is wildly uncertain.

That doesn’t mean tech is dead. It’s not. But investing in it now requires a different mindset. A new level of scrutiny. A willingness to question old assumptions. You have to ask not just what a company does, but how it defends its advantage when everything is open source, instantly replicable, and moving at the speed of compute.

At the same time, it might be time to give more attention to the parts of the market that haven’t been fashionable – sectors where the rules are slower, stickier, and maybe more boring. Because boring isn’t bad. In a world chasing novelty, durability is the ultimate edge.

Portfolio construction isn’t about picking winners – it’s about managing uncertainty. And the biggest risk right now isn’t missing the next OpenAI or Anthropic (and we still have to see whether these venture bets will have a big payoff anyway). It’s anchoring your portfolio to a version of tech that no longer exists.

AI will change a lot. But it won’t change everything. And in the end, the best portfolios won’t be the ones that predicted every twist in the hype cycle – they’ll be the ones built on a foundation that still holds when the hype fades.

So yes – build for the future. Embrace what’s coming. But do it like it’s 2025. Not 2015.

AI will analyze the data. Turning that into insight? That’s the investor’s job.

I’m more investing in the backbone of the AI revolution - Arista Networks cloud networking, Constellation Energy’s nuclear energy (ai usage requires energy; nuclear is the cleanest and most practical), looking for plays like that that work no matter who wins the ai race!