Playing a Different Game: When Fundamentals Aren’t Enough Anymore! (Part 1)

Rethinking fundamentals, timing, and how value actually gets realized

This will be a 3-part series. If you don’t want to miss the follow-up pieces, make sure to subscribe to the blog.

I want to start this series with a small confession. Towards the end of last year, when I recorded a podcast with Niklas from Heavy Moat Investments, we talked about our biggest lessons from 2025. My answer surprised me a little as I said it out loud.

I told him that I had become much more open to the idea of “(market) timing” – and yes, I deliberately put market in brackets.

What I really meant was timing in a broader sense. Timing entries. Timing exits. Paying closer attention to when I deploy capital and when I step aside, even if the underlying business thesis remains intact. That answer would have felt uncomfortable for me a few years ago, I must say. Today, it feels like I’m more honest with myself and the changes in market structure over recent years that have become more and more obvious ever since COVID.

In this context, I have to refer to Michael Mauboussin, who argues that there are only three ways to express skill in investing:

security selection,

position sizing and

timing.

I wrote about this framework in my Half-Year Investor Letter and specifically focused on position sizing. You can find the letter here:

Those are the levers. You can generate alpha by being better at picking stocks. You can generate alpha by sizing positions more intelligently. And you can generate alpha by being better at timing – when you enter, when you add, when you reduce, when you exit.

For a long time, I focused almost exclusively on the first two. I don’t regret that. In fact, you can do extremely well just pulling those levers. And I mean extremely well!

But ignoring the third entirely starts to look less like discipline and more like … stubbornness. It’s important to always be open with yourself and biases you inevitably develop over time. Most value investors develop a “value bias” over time and reject any other approach as nonsense.

But especially once you really internalize how compound interest works, how can you ignore a lever that may help you add a few percentage points to your long-term CAGR? Adding one or two percentage points to your long-term return doesn’t sound dramatic. Compounded over decades, it is anything but small. It is massive. It’s life-changing. Will be worth MILLIONS of dollars.

Someone who really pushed me to think about this differently was Tiho Brkan. At some point last year, he told me something that stuck. He said that, for me personally, the incremental return on time spent improving my “timing muscle” was likely far higher than the return on spending even more time refining my fundamental analysis. His point wasn’t that fundamentals don’t matter. Quite the opposite. It was that fundamentals are already where I spend most of my time and where, at the risk of sounding arrogant, I believe I already have a meaningful edge over the average market participant.

Timing, on the other hand, remains underdeveloped in my process. I still carry a strong “value bias.”

So I’ve been thinking about this expanded framework for at least half a year, probably longer, and yet I’ve barely leveraged it in practice. That tells me something. Transitions like this take time. Writing about them is part of the work. That’s what I attempt to do in this multi-part series. And that’s what I actually did last year when I wrote about market timing, and in hindsight, I believe it was one of the better pieces I published in 2025.

In a way, this series is a continuation of that line of thinking, but with a much sharper focus on timing entries and exits in individual stocks rather than trying to time the market as a whole or call macro turning points.

Another major influence was an episode of the Value Investing with Legends podcast with guest Ricky Sandler, titled “Investing Through Perception Shifts and Market Cycles,” published on December 19, 2025. Much of what I explore in this first post of the series is inspired by how Sandler articulates the idea that markets have changed and that investor perception has become a far more important driver of prices than many fundamental investors are willing to admit. I’m trying to integrate some of his into a framework that still starts with fundamentals but then adds the timing layer on top. When I later get into the more quantitative and technical instruments I use to express this approach, voices like Tiho’s, Jessica Ablamsky, and Mike, with whom I recorded the Wise episode, will play a much stronger role.

And with that out of the way, let’s get into the main sections of this post.

Before we dive back in, a quick note…

Want to compound your knowledge – and your wealth? Compound with René is for investors who think in decades, not headlines. If you’ve found value here, subscribing is the best way to stay in the loop, sharpen your thinking, avoid costly mistakes, and build long-term success – and to show that this kind of long-term, no-hype investing content is valuable.

Disclaimer: The analysis presented in this blog may be flawed and/or critical information may have been overlooked. The content provided should be considered an educational resource and should not be construed as individualized investment advice, nor as a recommendation to buy or sell specific securities. I may own some of the securities discussed. The stocks, funds, and assets discussed are examples only and may not be appropriate for your individual circumstances. It is the responsibility of the reader to do their own due diligence before investing in any index fund, ETF, asset, or stock mentioned or before making any sell decisions. Also, double-check if the comments made are accurate. You should always consult with a financial advisor before purchasing a specific stock and making decisions regarding your portfolio.

When Fundamentals Stopped Being Enough on Their Own

For a long time, my implicit mental model of markets was simple. If I understood a business better than most, normalized earnings sensibly, and bought at a price that embedded too pessimistic assumptions, the gap between price and value would eventually close. Maybe not next quarter. Maybe not next year. But eventually. Time, in that framework, was a tailwind. And if you add incremental earnings power growth on top of this, you end up with a sweet, market-beating return.

That belief was not naïve. It reflected how markets actually worked for decades. Prices were largely set by investors doing bottom-up work, comparing businesses against each other, arguing about margins, returns on capital, growth durability. In that world, mispricings tended to correct because the investor base itself was doing the work required to correct them.

What has changed is not the relevance of fundamentals. It’s the reliability of that closing mechanism.

That insight is not unique to Ricky Sandler. It has been voiced, far more bluntly, by David Einhorn, who has spent the last few years openly questioning whether traditional value investing still works at all. In a widely discussed Bloomberg interview, Einhorn described what he called the wreckage of professional value investing. He spoke of “serious changes to the market structure” and argued that “most value investors have been put out of business.”

Statements like these understandably led many investors to conclude that the style itself might be dead. After a long stretch of disappointing performance, it’s not hard to see why both managers and clients have been tempted to move on.

But Einhorn’s argument is more nuanced than the headline quotes suggest. In fact, he immediately follows that bleak assessment with a statement that should make any fundamental investor stop and think. He says,

“the other side of that is nobody knows what anything is worth, so there are an enormous number of companies that are dramatically misvalued.”

That sentence captures the tension at the heart of modern value investing. Fewer people are doing valuation work. Fewer prices are anchored to intrinsic value. On the surface, that sounds like an existential threat to our discpline. Look a layer deeper, and it may be the opposite.

I wrote a long thread on X unpacking Einhorn’s comments in more detail back in 2023, including excerpts from the Bloomberg interview and some of the implications I drew from it [read it here]. What struck me most while working through his argument was that Einhorn is not really saying valuation is useless. He is saying that valuation has lost its coordinating power. Investors who still value businesses based on discounted future cash flows are increasingly “playing a different game,” as he puts it, than the majority of market participants.

At its core, the logic is straightforward. Stock markets are auction-driven. Prices are set where supply meets demand.

If the marginal buyer in that auction does not care about intrinsic value, is unaware of the concept – or he/she is aware but doesn’t know it want to use it – then prices will not reliably reflect intrinsic value. It’s a reflection of market participants’ indifference. And indifference to price has become much more common.

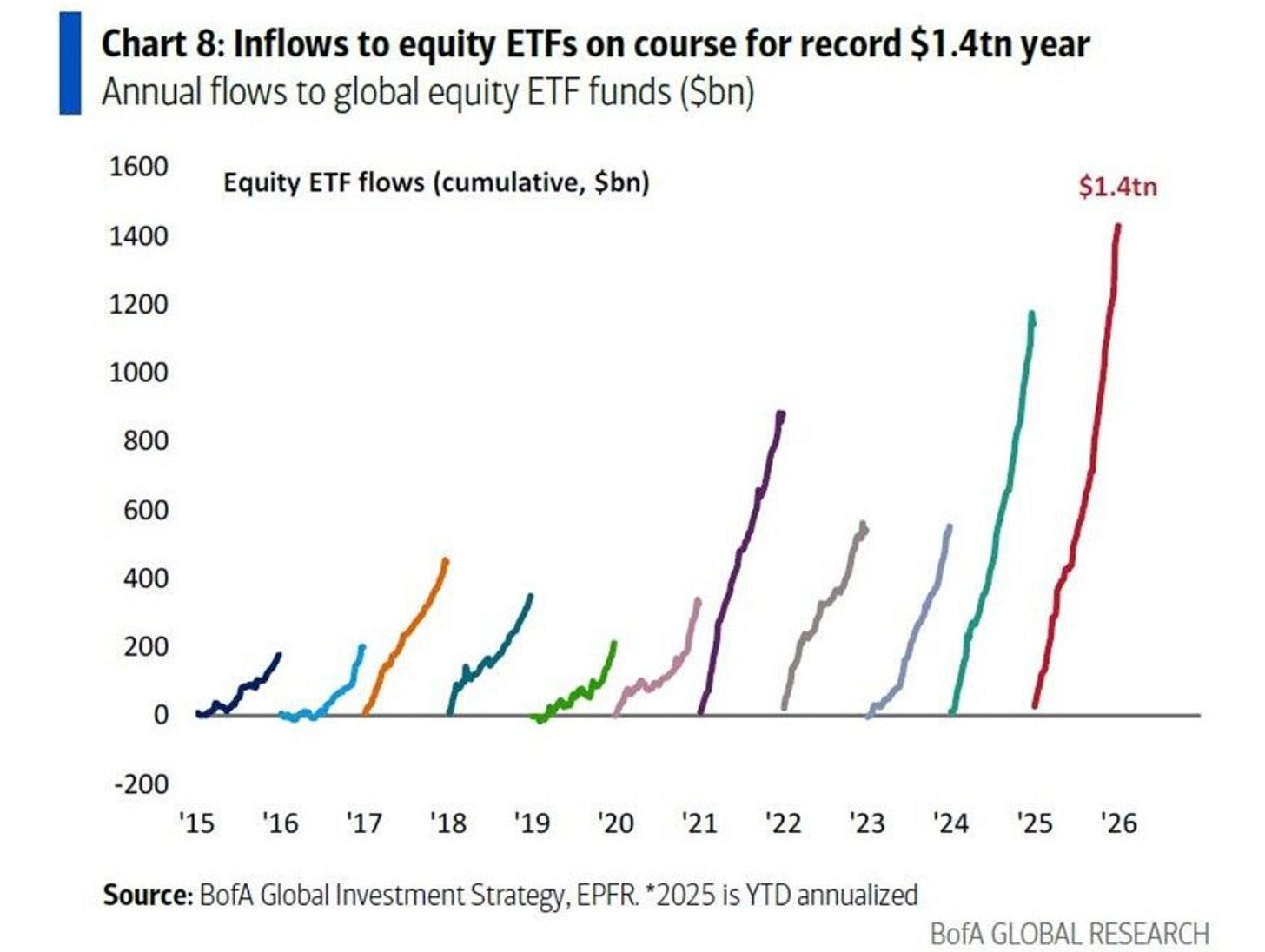

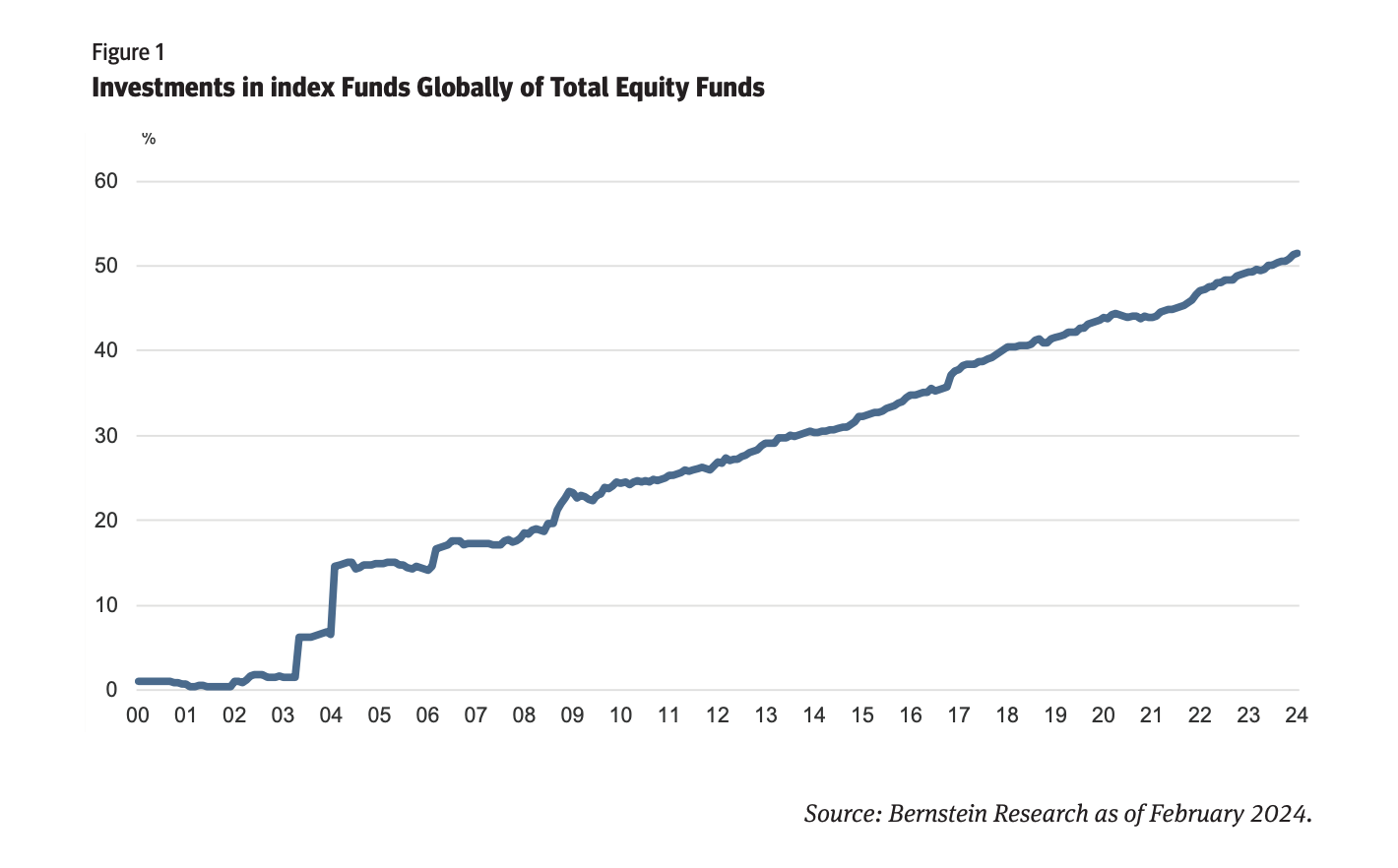

One of the main forces behind this shift is the rise of passive investing. Over the past decade, trillions of dollars have moved from active strategies into index products. Passive vehicles buy because a stock is in the index, not because it is cheap. They sell because of rebalancing, not because fundamentals deteriorated.

Einhorn also points to the growing dominance of sell-side analysts on conference calls and the increasing influence of quantitative strategies that trade based on factors like momentum, volatility, liquidity, or macro data rather than business value. Taken together, these forces help explain why prices can drift far from any reasonable estimate of intrinsic worth and stay there.

This is where the dilemma for fundamentally focused investors becomes acute. If fewer participants care about value, mispricings should, in theory, become larger and more frequent. That’s the bullish interpretation.

But if fewer participants care about value, the mechanism that used to close those mispricings weakens. Valuation gaps no longer close simply because the gap exists. And that’s a problem for value investors.

Einhorn’s own response to this environment is telling. He has said that he is now much more focused on earning “a return based on what the companies are able to pay us.”

That shift forces you to think more carefully about the sources of equity returns.

Growth in earnings is one.

Changes in valuation multiples are another.

“What we are shooting for is earning outsized returns. So I want these two levers. I want the compounding of the business and the re-rating of the stock.“ - Ricky Sandler

But there is a third source that becomes more important when re-rating is unreliable: distributions to shareholders. Dividends. Buybacks. Any form of capital allocation that converts intrinsic value into realized returns without requiring the market to change its mind.

This does not mean abandoning valuation. If anything, it raises the bar. When “nobody knows what anything is worth,” capital allocation skill becomes decisive. Buybacks only create value if shares are repurchased below intrinsic value. Dividends only compensate for stagnant prices if the underlying business can sustain them. In a market where perception may never shift, you need businesses that can force value realization themselves.

Illustrating Einhorn’s Take With An Example:

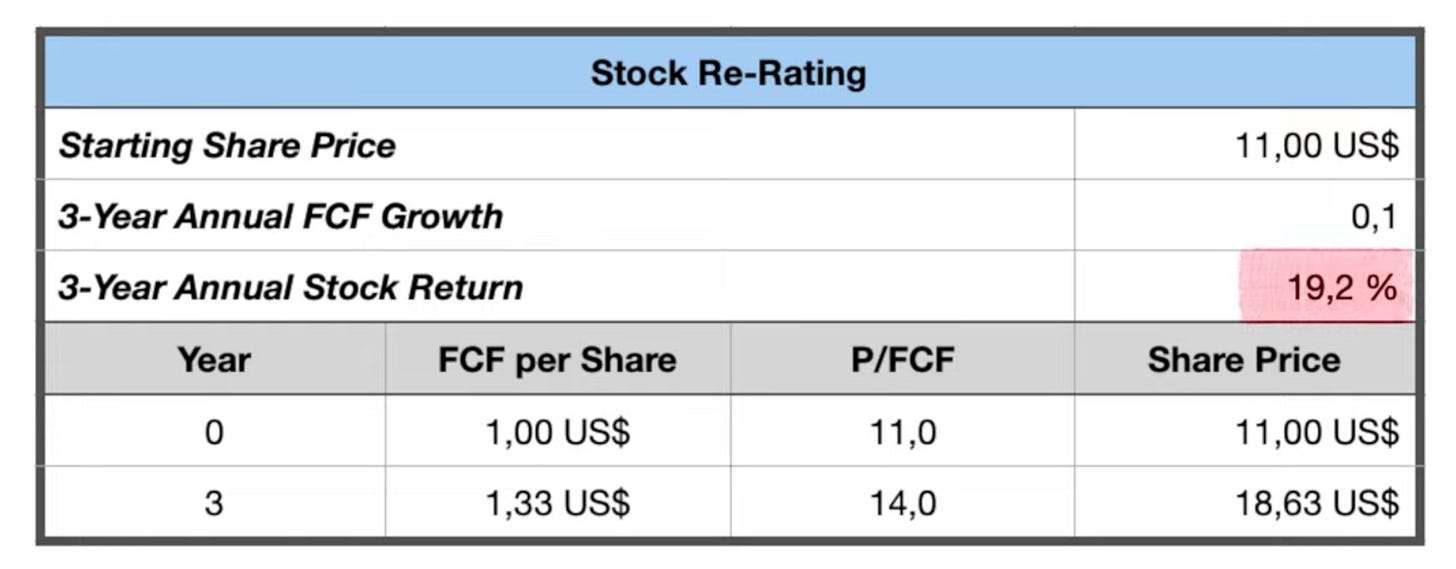

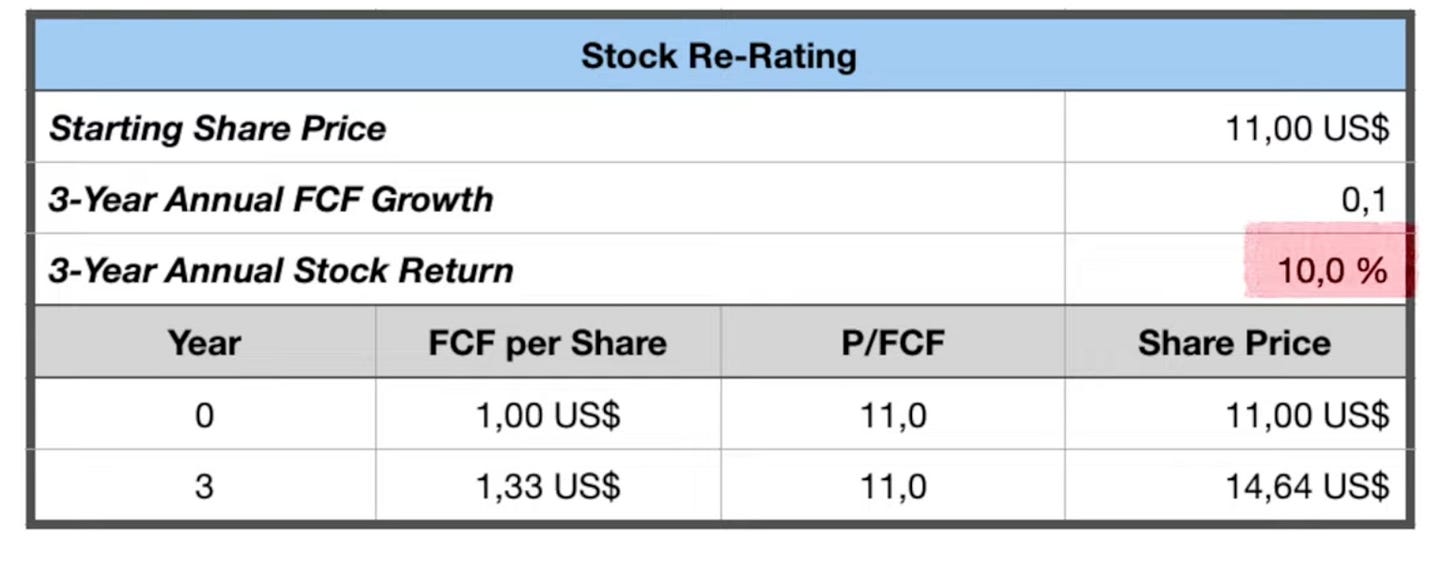

A simple numerical example helps make this new approach more tangible. Imagine a company trading at $11 per share, generating $1 of free cash flow per share. That’s an 11× free cash flow multiple. Assume the business grows free cash flow at 10% annually over the next three years. If, over the same period, the market decides to revalue the stock from 11× to 14× free cash flow, the result is a very attractive outcome. Your total return would approach 70%, or roughly 19% compounded annually. This is the classic value investing playbook. Earnings grow, the multiple expands, and fundamentals and perception move in sync.

Now remove one assumption. Keep the growth. Remove the re-rating. If the multiple stays flat despite the improvement in free cash flow, your return suddenly looks very different. You’re left with something close to the business growth rate itself. That may still be acceptable, but it is a far cry from what many investors implicitly expect when they underwrite a “cheap stock with growth.”

Now the multiple might also decline if the market doesn’t care about fundamentals anymore. What if the multiple declines from 11x to 8x? Well, all of a sudden you end up with pretty terrible returns despite buying a growing business at a cheap price.

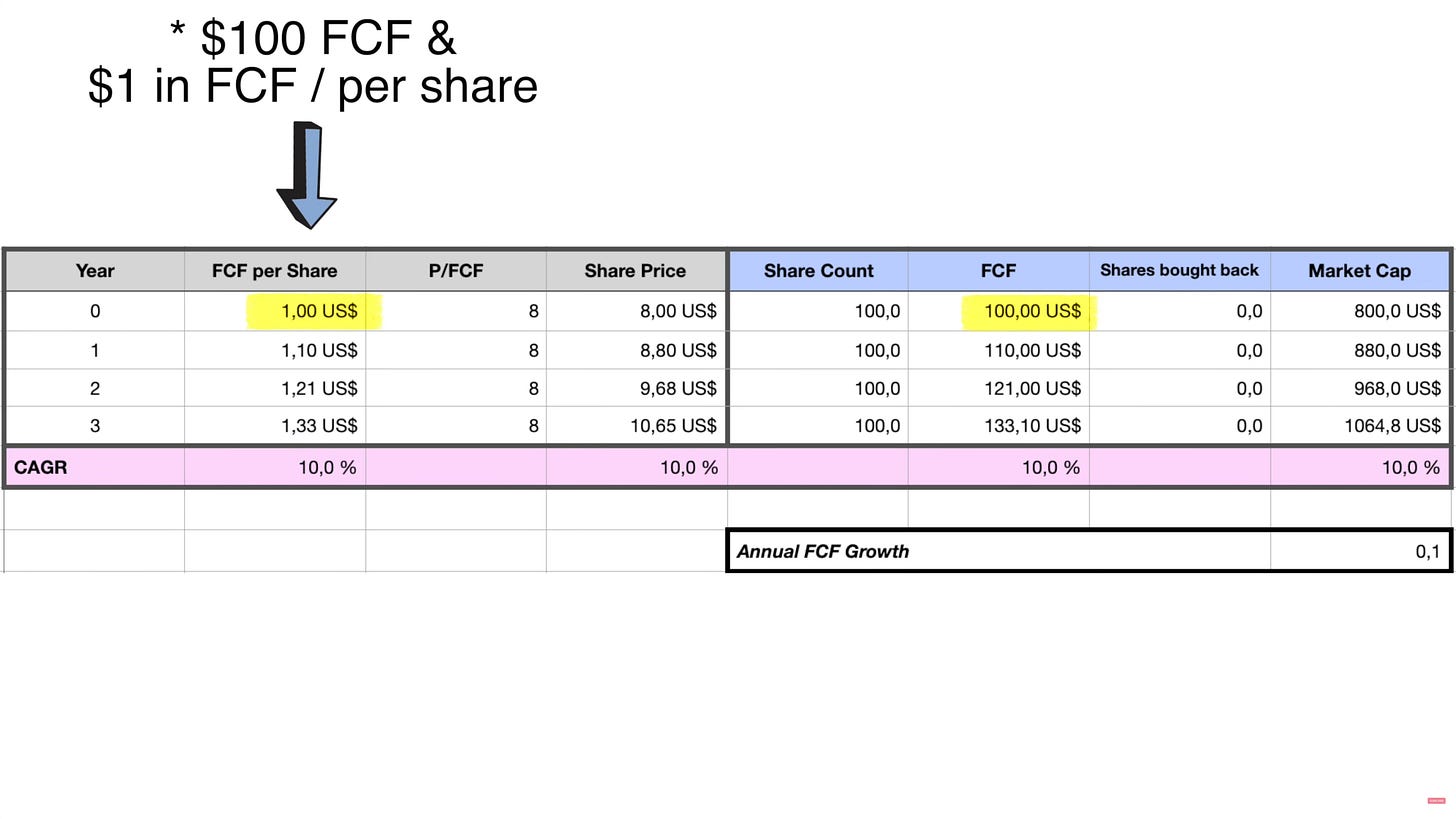

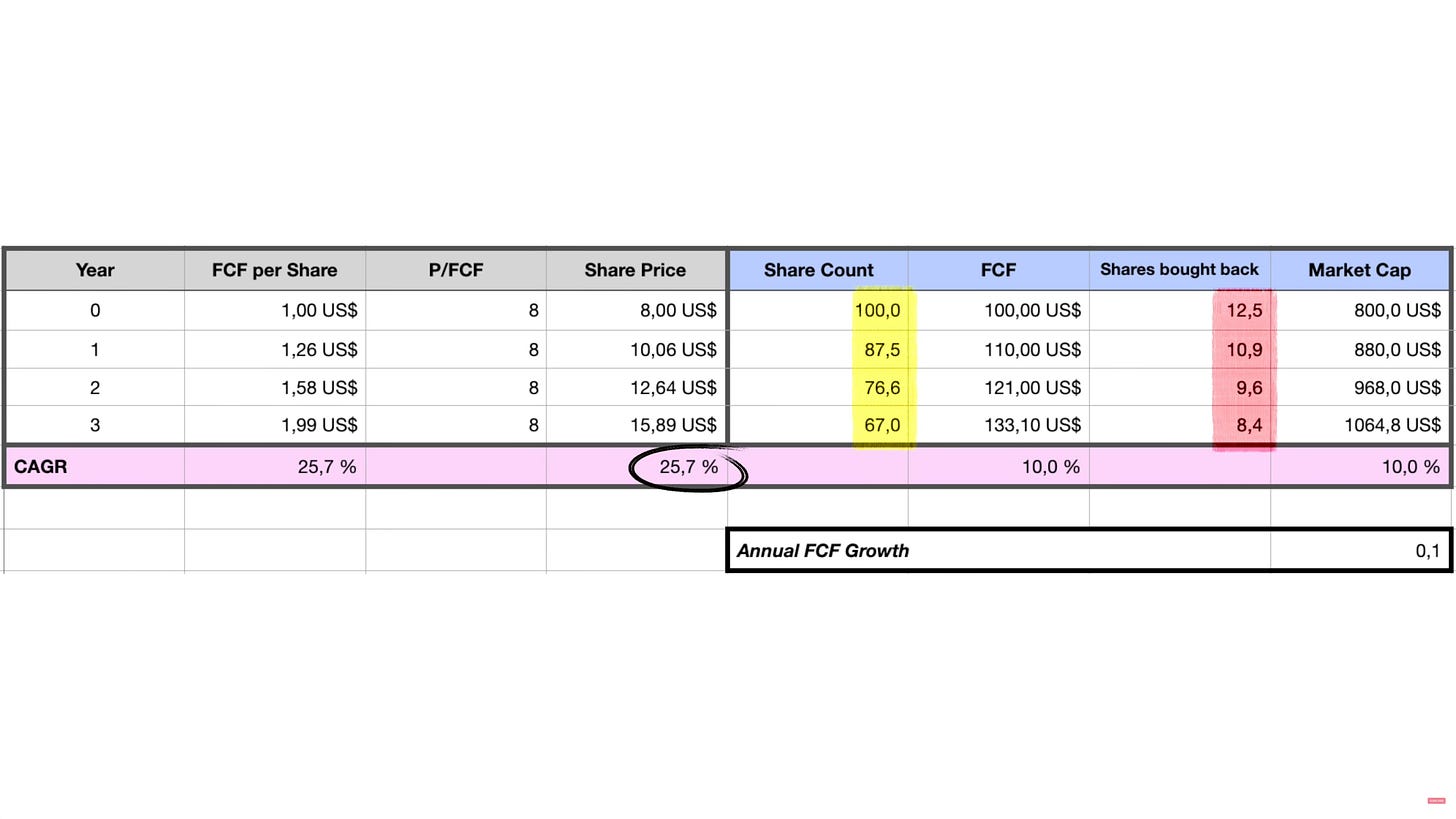

This is where the third source of return becomes decisive. Suppose management recognizes that the stock is undervalued at 8x FCF and decides to use all available free cash flow to repurchase shares in the open market. As the share count shrinks, each remaining share represents a larger ownership stake in the business. Even without any multiple expansion, the math starts to work in your favor. In this scenario, buybacks alone can dramatically lift the compounded return, turning a middling outcome into a very strong one.

Comüare the company not buying back any shares (a 10% share price CAGR) …

… to the one that does so aggressively (a 25x share price CAGR assuming the multiple remains constant):

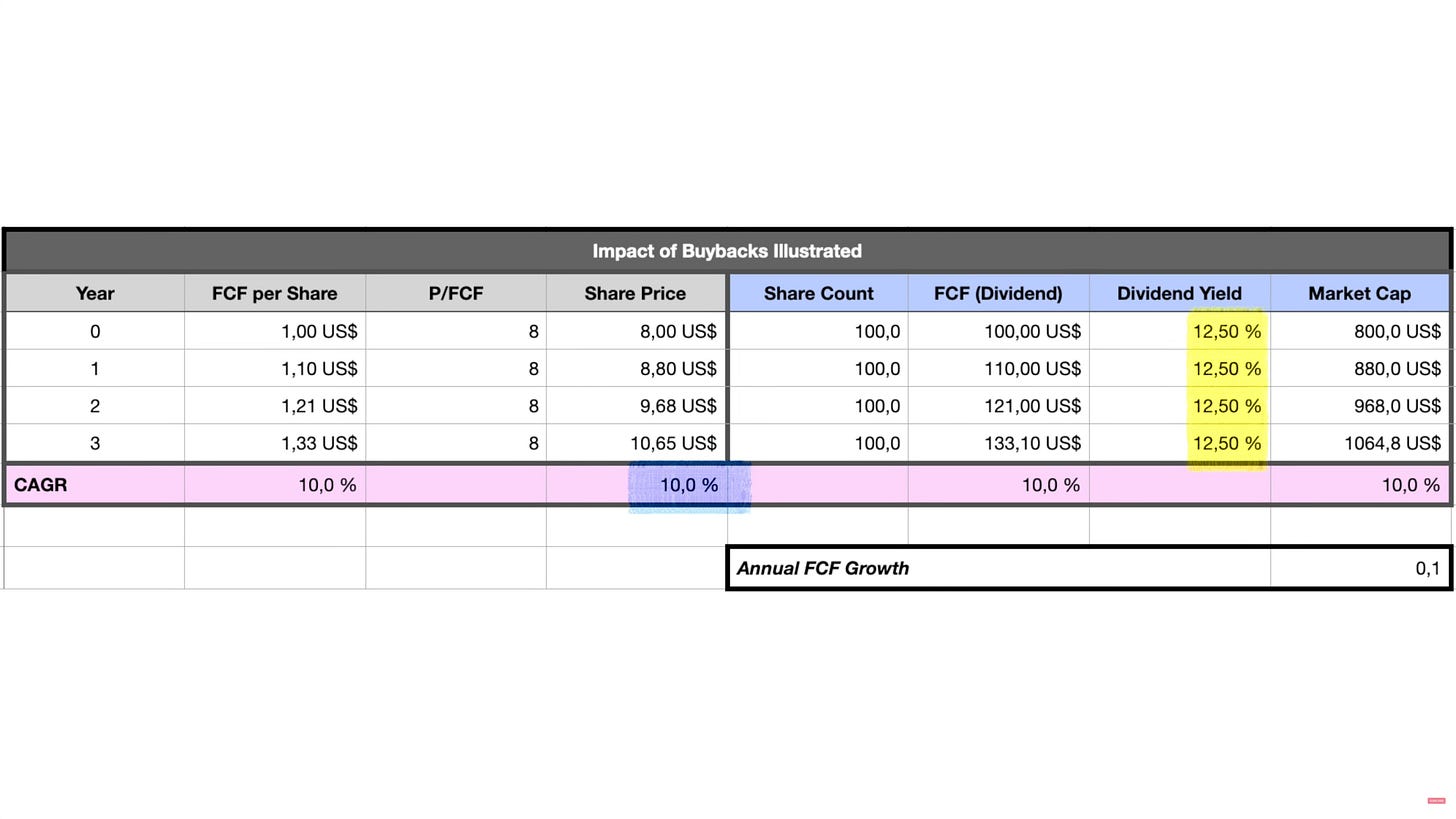

The same logic applies to dividends. If the company distributes most or all of its free cash flow to shareholders, the return no longer depends on the market waking up. You get paid while you wait (a 22.5% pre-tax return in the example below).

Of course, this cuts both ways. Buybacks only create value if shares are repurchased below intrinsic value. Dividends only help if the underlying business can sustain them without eroding long-term earning power. Capital allocation is not a footnote in this framework. It’s central.

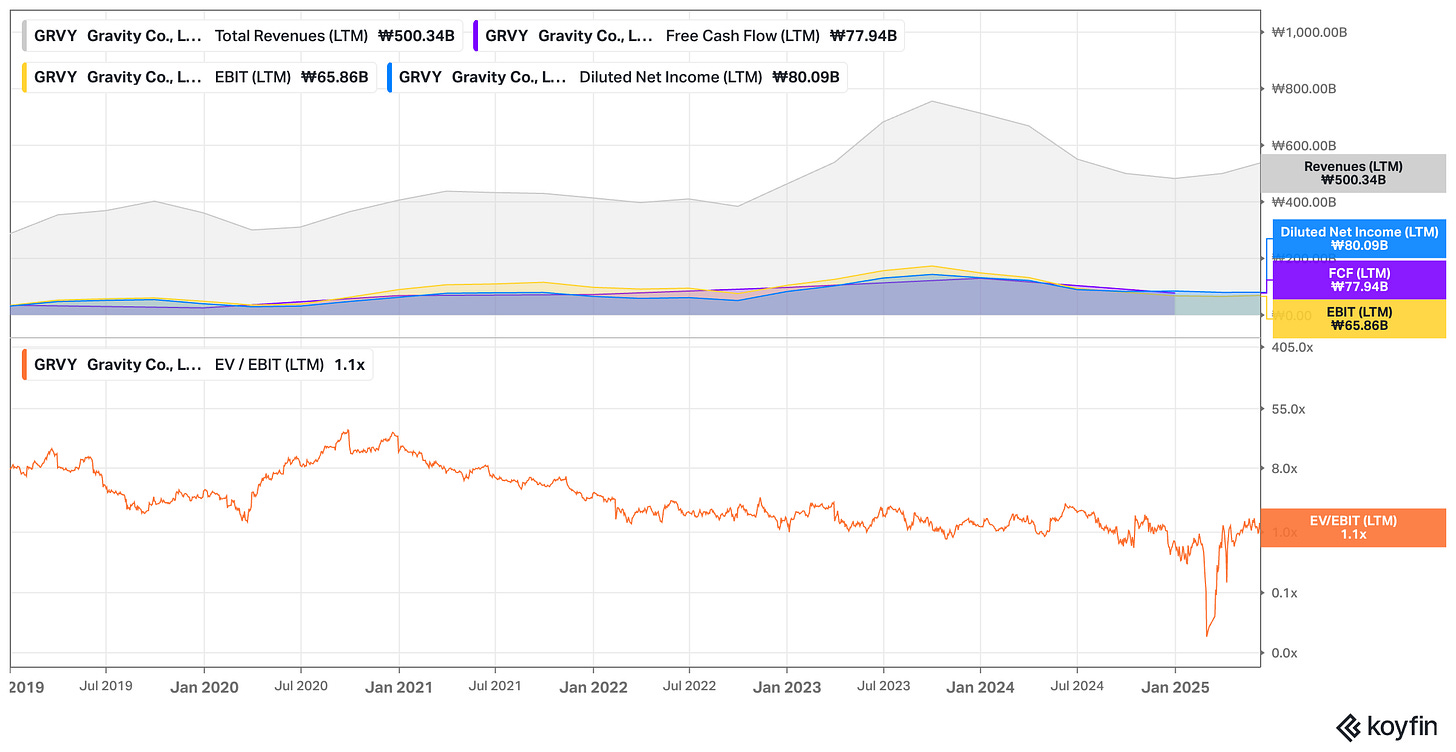

Now, this is only theoretical so far, let’s look at a real-world company I referred to back in 2023: One of the most frustrating examples I’ve encountered personally was my past investment in Gravity. At one point, the stock traded at roughly one year’s worth of operating income. By almost any valuation framework, it was absurdly cheap. And yet, management refused to buy back shares or return capital in any meaningful way. Cash piled up on the balance sheet. Value remained trapped. In a market where perception alone might never shift, that refusal turned what looked like a no-brainer into an uninvestable situation.

Interestingly, today, almost three years after writing the thread, Gravity’s stock still hasn’t gone anywhere …

… despite improving fundamentals (revenue and profits up):

The stock still trades at a ridiculous valuation. It’s a textbook example of both Einhon and Sandler’s point! One of the most dangerous assumptions in fundamental investing is that cheapness is self-correcting. That assumption used to be reasonable. It’s much less so today.

“Beginning to realize that the gap in value, the time it would take, if you didn't understand why a stock was mispriced and didn't understand what could change that misperception, you could have something that stayed cheap for a very, very long time.“ - Ricky Sandler

The cost of that is not just opportunity cost. It’s also psychological. Extended periods of underperformance test conviction, capital, and client patience.

This is the uncomfortable conclusion you’re forced to confront once you take Einhorn’s argument seriously. If valuation gaps no longer close reliably, you cannot rely on re-rating as a default outcome. You either need a credible path for perception to change, or you need businesses that can deliver returns without asking the market for permission. In today’s market structure, ignoring that distinction is no longer a benign oversight.

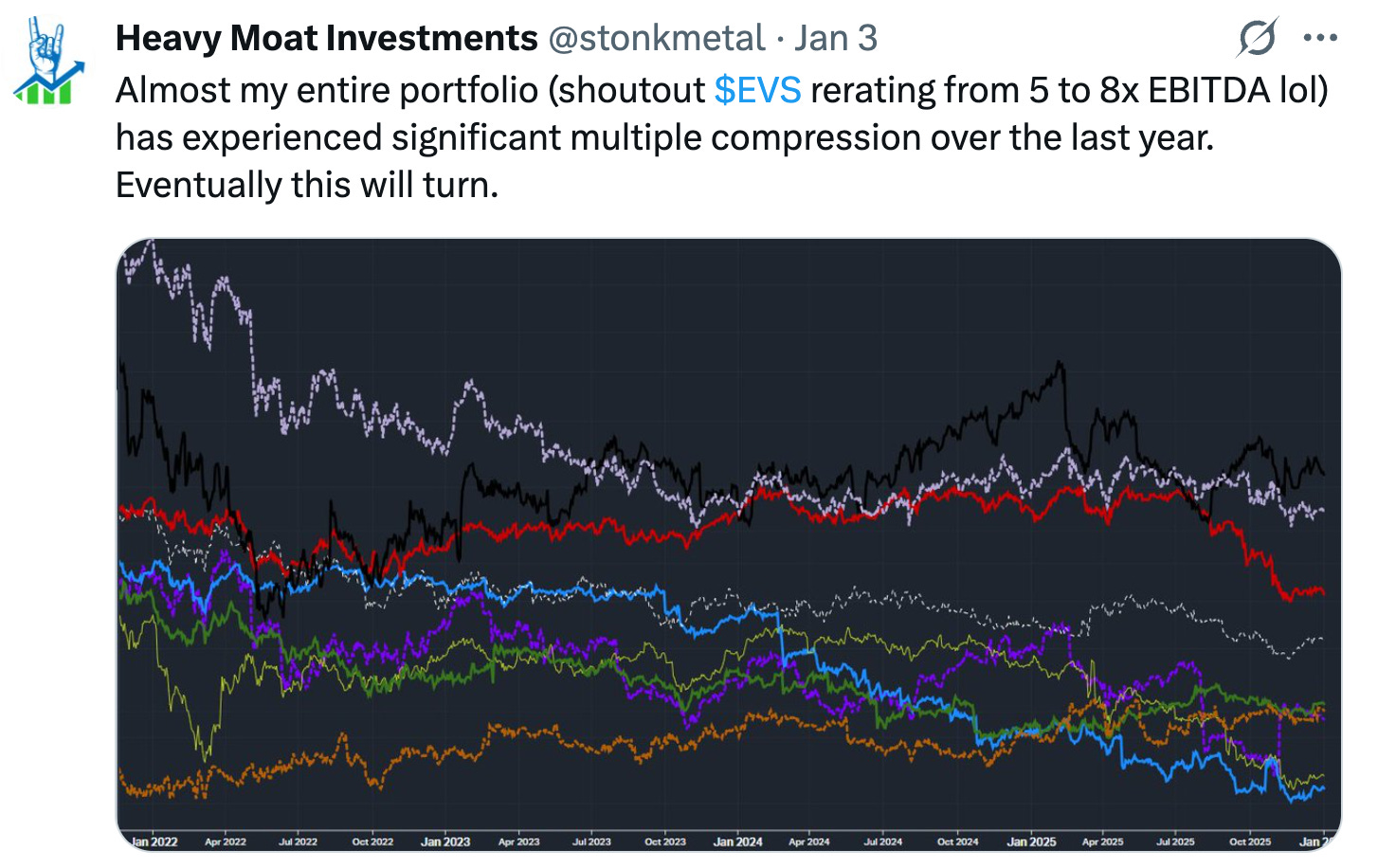

“Surely there is some way to not buy as much into a falling knife because that has been the majority of what I did this year, buying improving business fundamentals while the stock keeps declining.“ – Niklas during our recent podcast episode

Disclaimer: The analysis presented in this blog may be flawed and/or critical information may have been overlooked. The content provided should be considered an educational resource and should not be construed as individualized investment advice, nor as a recommendation to buy or sell specific securities. I may own some of the securities discussed. The stocks, funds, and assets discussed are examples only and may not be appropriate for your individual circumstances. It is the responsibility of the reader to do their own due diligence before investing in any index fund, ETF, asset, or stock mentioned or before making any sell decisions. Also double-check if the comments made are accurate. You should always consult with a financial advisor before purchasing a specific stock and making decisions regarding your portfolio.

The Six “P”s of Market Structure Changes

Back to Ricky Sandler. He describes this shift very explicitly as well when he reflects on how his own framework evolved after the global financial crisis. He notes that early in his career,

“it was enough to have the right business at the right price and things took care of themselves because most market participants were doing bottoms up research.”

That assumption no longer holds. He goes on to explain that as markets shifted toward passive flows, thematic investors, and increasingly short-term decision-making, “the dislocations from value were persisting for longer and for wider amounts of time.”

A helpful framework for thinking about modern market structure is a simple one: asking what actually drives prices in the short to medium term. Ricky Sandler spends a meaningful part of the conversation explaining why his framework had to evolve, and much of what he describes maps cleanly onto what I think of as the six “P”s of today’s market.

None of these forces are new in isolation. What’s new is their scale, their interaction, and their growing dominance over traditional valuation-driven decision-making.

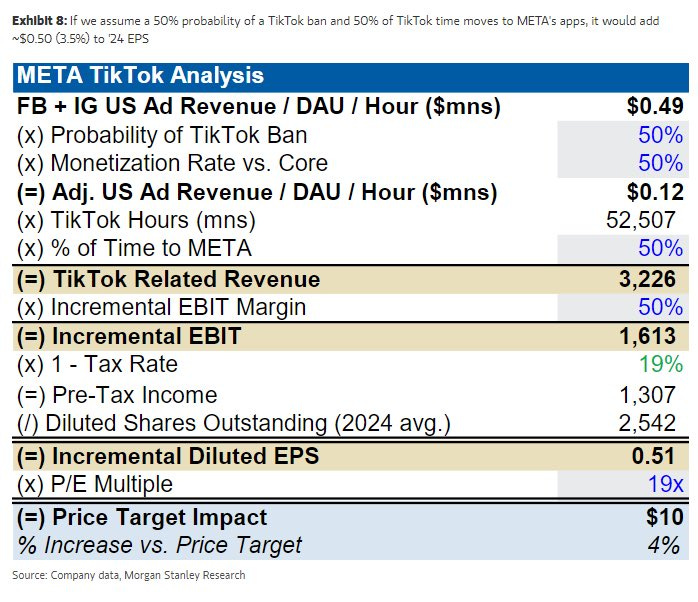

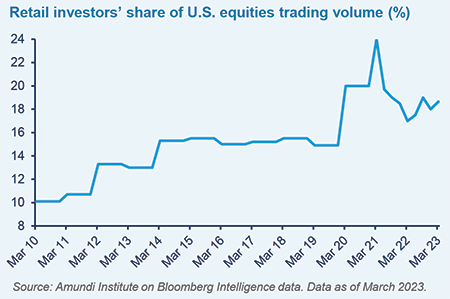

The first and most obvious force is passives. We already highlighted this. Index funds and ETFs allocate capital mechanically, based on index weights rather than business fundamentals. Sandler describes how markets shifted away from being dominated by bottom-up investors toward ones “driven by passive flows” and thematic capital (see chart below to back this up with numbers). Indices don’t care about normalized earnings or long-term cash flows. Yet they represent an ever-growing share of daily trading volume and ownership. That alone weakens the link between price and intrinsic value.

Closely related, but more subtle, are “pod shops” – multi-manager platforms and short-horizon trading desks operating under tight risk constraints. The Motley Fool defines those as “[…] a type of investment firm that employs multiple independent teams (or pods) to manage capital. Each team has a specific mandate, style, and edge, and they operate relatively autonomously within the overall structure of the pod shop.“ These investors are often evaluated over weeks or months, not years. Sandler makes this point very explicitly when he talks about “a whole cadre of investors today who are investing on a three-week, a three-month time frame. And what they’re doing has nothing to do with the business and everything to do with the stock and what’s going to make the stock work.” So what matters in a world of “pods” is not whether a business will compound over a decade, but whether a stock will work over the next few reporting cycles. This short-termism amplifies volatility around earnings, guidance changes, and narratives, and it compresses the time window over which fundamentals are allowed to matter.

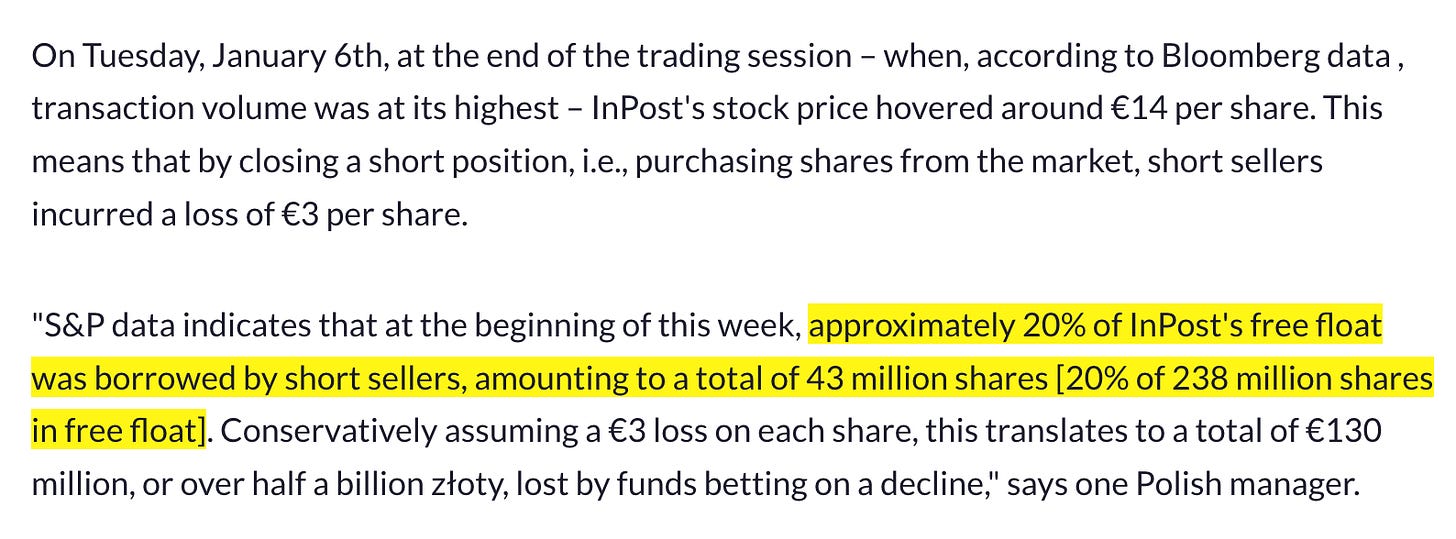

Then there is positioning, particularly on the short side. Stocks don’t trade in a vacuum. They trade with an existing shareholder base, embedded expectations, and often crowded exposures. When positioning becomes one-sided, price movements can have very little to do with new information. Sandler alludes to this when he talks about stocks screening poorly in quant baskets, suffering from negative estimate revisions, or being excluded from certain investor universes. Once a stock becomes “unownable” for a segment of the market, selling pressure can persist well beyond what fundamentals would justify. Conversely, when positioning unwinds, perception can flip quickly, sometimes without any real change in the underlying business. InPost came to my mind as a prime example. Apparently, 20% of the free float was borrowed by short sellers despite improving fundamentals of the company and a share price that was down around 50% in a little over a year (before the take-private offer was made public earlier this year).

Processors – algorithms and systematic strategies – are another major force. These strategies don’t interpret businesses. They process data. Factors like momentum, volatility, liquidity, revisions, or correlations drive decisions. Sandler notes that momentum, defined by six- and twelve-month returns, is “one of the most powerful signals over the long term.” Whether that makes intuitive sense is almost beside the point. Enough capital responds to these signals that they become self-reinforcing. A stock with negative momentum attracts selling because it has negative momentum. That selling sustains the momentum. Fundamentals may eventually break the loop, but not always quickly, and not always cleanly.

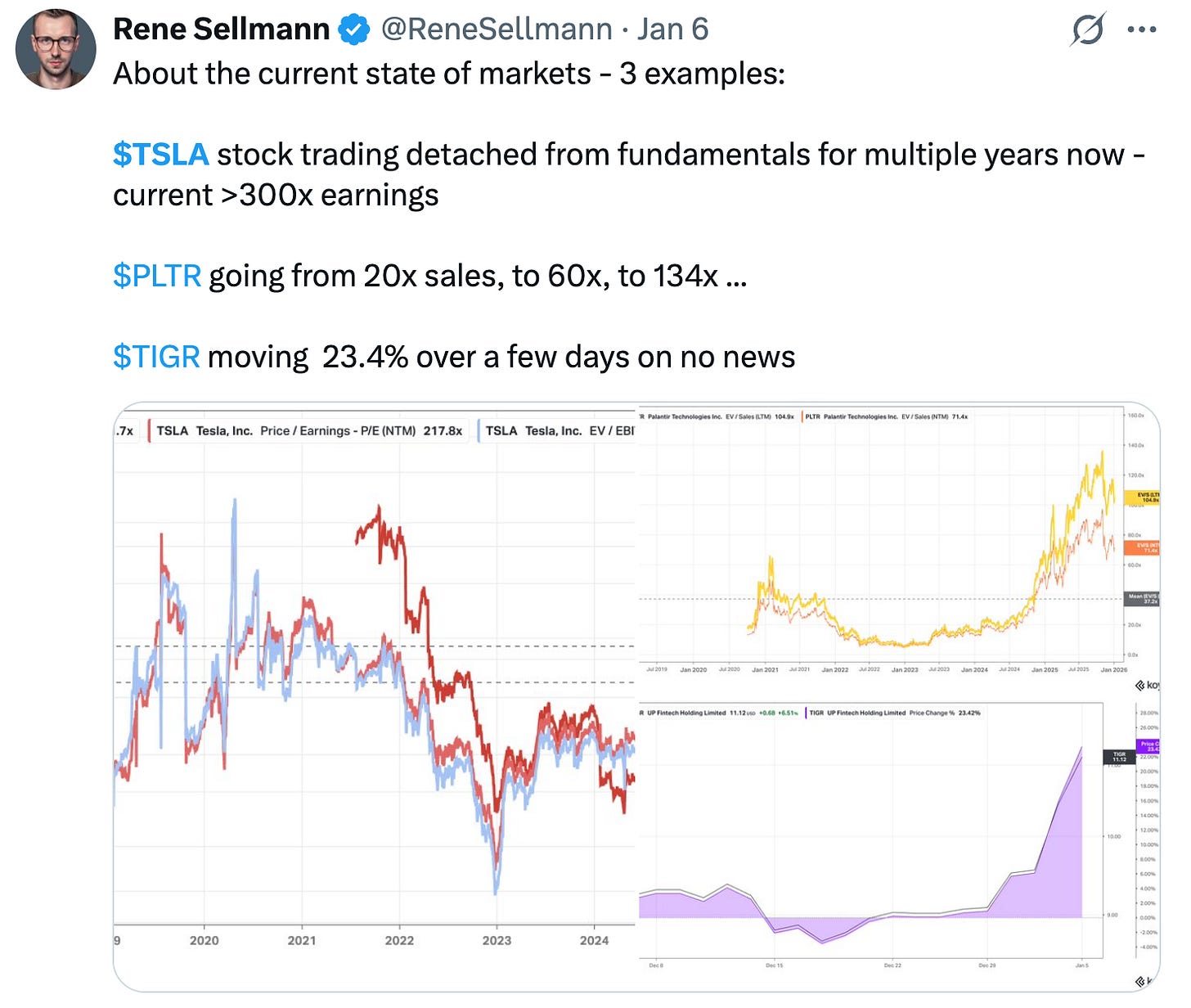

People – retail investors – form the fifth P. Retail participation has surged, aided by frictionless trading, social platforms, and constant information flow. Retail flows are often narrative-driven rather than valuation-driven. That doesn’t make them irrational, but it does mean they respond to different stimuli. Stories, themes, sentiment shifts, and social validation can all move prices in ways that are difficult to reconcile with discounted cash flow models. In certain stocks, especially smaller or higher-volatility names, retail participation can meaningfully influence price behavior, at least for extended periods (I referred to Palantir and Tesla as prime examples above).

The sixth P, which Sandler himself emphasizes, is perspective – his term for the narrative surrounding a stock. This is where everything else converges. He repeatedly comes back to the idea that stocks don’t rerate because someone thinks they should. They rerate because other investors who believe it’s only worth 12 times today change their mind. Perspective is what has to change for that to happen. Narratives about growth, durability, cyclicality, disruption, or obsolescence shape how investors interpret the same set of facts. And because today’s market is dominated by participants who rely on heuristics, themes, and signals, narratives can matter as much as numbers, sometimes more, at least in the short to medium term.

“It’s not going to 18 times because you think it’s worth 18 times. It’s going to go to 18 times because other investors who believe it’s only worth 12 times today changed their mind and they now believe it’s worth 18 times because they think the future beyond that point warrants it or the company’s characteristics warrant it. Beginning to realize that the gap in value, the time it would take, if you didn’t understand why a stock was mispriced and didn’t understand what could change that misperception, you could have something that stayed cheap for a very, very long time.”

Taken together, these six forces explain why prices often behave in ways that feel disconnected from fundamentals. They also explain why valuation gaps can persist, widen, or suddenly close without any obvious catalyst. This is the environment in which fundamental investors now operate.

Returns Come from Multiple Engines

In the segment focused on Einhorn’s recent takes, we highlighted the three sources of return: earnings growth, changes in valuation multiples, and direct distributions.

Most fundamental investors already focus on the first lever. We spend enormous amounts of time thinking about durability, reinvestment opportunities, competitive advantage. That work remains essential.

Einhorn flagged how you should place a stronger emphasis on the “distribution source” by betting on management teams capable of identifying mispricings and exploiting them with the help of their capital allocation toolkit.

Sandler placed a stronger emphasis on the re-rating lever, driven by perception change. Sandler’s sweet spot, as he describes it, is owning stocks for two to four years and capturing “multiple years of compounding along with a significant re-rating.” That time frame is long enough for fundamentals to matter, but short enough that perception has to shift for returns to be realized.

But how do you spot changes in perception leading to changes in valuation multiples? Well, this is what we are going to cover in the second (qualitative instruments) and third part (quantitative instruments) of this series. Timing becomes everything. And so you need to work on your “timing skills!”

Bottom Line

This first part is deliberately theoretical. Before talking about tools, signals, or techniques, it’s necessary to accept that the rules of the game have changed. Not completely. Not irreversibly. But enough that ignoring those changes becomes a liability.

Fundamental analysis still tells you what should happen over the very, very long term. Market structure and perception analysis help you understand when and why it might actually happen.

The rest of this series builds on that distinction.

Big thanks so far! Great article

Great read