Investing in Software When AI Agents Arrive – A Framework for Who Gets Disrupted

Based on Gokul Rajaram Invest Like the Best Appearance

Software stocks are getting crushed. Not selectively. Not tactically. Almost indiscriminately!

If you scan the sector today, the picture looks less like a rotation and more like a liquidation, maybe even capitulation – growth leaders, category winners, infrastructure platforms, horizontal SaaS, vertical SaaS, all bleeding together.

The chart below I came across on X today captures this brutally well: across dozens of well-known software companies, drawdowns from recent highs cluster around levels that would normally be associated with existential crises rather than cyclical uncertainty.

It looks like when it comes to investing, “Hardware” is the new “Software.” - Paul Andreola

This feels like a collective repricing of what software is worth in a world where AI agents can increasingly do what software used to do, and where the durability of cash flows is questioned. Maybe you have visibility into the next two years, but what about 2030 and beyond? Can you have confidence in the cash flow production capabilities of most SaaS names?

From a stock picker’s perspective, this is paradoxically close to an ideal environment. What more could investors hope for? An above-average sector – which I believe “software” is – being sold with almost no discrimination between fragile business models and genuinely durable ones?

This is precisely the kind of regime in which careful company-specific analysis can matter again. When capital exits an entire category because it feels “too hard,” or because of “career risk” because one can’t see light at the end of the tunnel yet, the opportunity is rarely that everything is broken.

More often, it is that the market has stopped distinguishing between fundamentally different types of businesses.

I recently came across a tweet that captured this mood perfectly. The argument was that what we are watching is not a normal drawdown but a loss of confidence in an entire business model by investors who cannot afford to be wrong on a one-year horizon. When uncertainty rises, nuance disappears. Portfolios get simplified. Complex theses get abandoned. Software becomes a single trade rather than a spectrum of economics.

At the same time, the competitive boundaries of software are visibly shifting. Robinhood, historically a brokerage platform, is now experimenting with full-service tax filing, estate planning, and dedicated financial advisors – bundled into a single app experience. This is not just product expansion. It is a signal that the traditional borders between software categories, financial services, and professional services are eroding.

When software becomes cheaper to build and easier to distribute, adjacent industries start to collide. The question for investors is no longer whether disruption will happen, but where it will hit first and how deeply it will cut into existing profit pools.

This is why the very recent episode of the Invest Like the Best podcast with guest Gokul Rajaram felt unusually important to me. I’ve summarized key takeaway of many episodes from the show – the most recent one being the Henry Ellenbogen show – so let me once again give a major shoutout to Patrick O’Shaughnessy for the incredible value he creates by sharing these episodes freely.

Learning from Henry Ellenbogen

A few days ago, I came across the fairly new Invest Like The Best episode featuring Henry Ellenbogen, founder of Durable Capital Partners.

Rajaram has built products at Google, Facebook, Square, and DoorDash and invested in more than 700 companies. In the first half of the conversation, he does not offer a generic “AI will change everything” narrative. Instead, he implicitly lays out a set of mental models for distinguishing between software businesses that are structurally vulnerable and those that are surprisingly resilient.

When you connect his ideas about systems of record, pricing models, data durability, workflow depth, and stickiness, something close to a coherent framework emerges – one that can help investors think more precisely about which software stocks are most prone to disruption and which ones are quietly protected by deeper moats than the market currently acknowledges.

In what follows, I’ll try to reconstruct and extend that framework. Not as a checklist, but as a way of thinking about software economics and durability in the age of AI agents – and, ultimately, as a lens for navigating what might be the most indiscriminate sell-off the sector has seen in years.

The Wrong Question to Ask

If you listen to most conversations about AI and software, they tend to revolve around a binary question:

Will AI disrupt software companies or not?

That framing is seductive because it’s simple, but it’s also deeply misleading. The question is not whether disruption happens. It is where it happens, how fast it happens, and which layers of the software stack are structurally exposed versus structurally insulated.

Gokul Rajaram presented a couple of angles to look at software businesses to assess their vulnerability – or defensibility:

1) Systems of Record vs. Everything Else

Rajaram makes a crucial distinction in that regard that he believes the market rarely prices correctly. He argues that legacy software companies fall into two fundamentally different categories:

systems of record and

software priced on utility or outcomes.

“The software companies that should be the most worried right now, is where they are pricing the product based on utility.”

Not all software is created equal. Some systems sit at the core of a company’s operations. Others live closer to the surface, where their functionality can be replicated, augmented, or gradually replaced without triggering organizational shock.

At the center of most enterprises sits what can be called a system of record. These are platforms where critical data accumulates over time: financial systems, core ERP platforms, CRM databases, healthcare records, legal repositories. They are not just tools. They are institutional memory. Replacing them is rarely a technical decision. It is a career decision that comes with significant career risk. The risk of breaking something fundamental is so high that even clearly superior alternatives often fail to gain traction.

“Every vertical has either a legacy, or somewhat new, what is called a system of record. Which is a system where most of the data is stored for that system. For example, in legal, there’s a company called Filevine or another company called Clio. In sales, it’s Salesforce. In healthcare, it’s Epic.”

“For something like Salesforce, you can’t just say, ‘I’m a much better CRM.’ If you look at CRM, what does the CRM contain? It contains your customer record. Your customer support system contains what your customers are complaining about. […] But guess what? None of your customers is ever going to move unless you build a simple, seamless way to take the Salesforce data and move it to your instance, the data from Jira and move it to your instance, the Zendesk data move it to your instance. So literally, it’s a two-year effort to build migration.”

Around these systems of record, a growing layer of software has emerged over the past decade. These tools automate workflows, improve collaboration, add analytics, or optimize specific functions. They are valuable, but they are not foundational. In many cases, they depend on the system of record rather than owning it. That dependency turns out to be decisive in the age of AI agents.

The key insight is that AI-native products naturally attack the outer layers first. They do not need to replace a core system to create value. Instead, they sit next to it, intercept workflows, automate tasks, and gradually reduce the economic relevance of the incumbent software. This is why disruption in software is often invisible in its early stages. Nothing breaks. Customers do not churn en masse. They simply start paying for fewer seats, using fewer features, and relying more on external automation. Over time, that quiet shift can hollow out a business model without ever triggering a major or dramatic migration event.

This dynamic also explains why incumbent software companies are increasingly defensive. When core platforms realize that external agents are treating them like “dumb databases,” their instinct is to close access, bundle competing functionality, or charge for data extraction. The strategic logic is clear: if value is leaking through interfaces, the interface itself becomes the battlefield.

“In 2024, things changed. These companies started seeing that these agent companies, AI companies that are being built, they are starting to take on the functionality out of these companies and are treating them like a dumb database. So you started seeing last year that these companies are cutting off access to APIs.”

For investors, this distinction between core systems and peripheral software is more than a technical nuance. It is the first structural dimension of disruption risk. A company whose product is deeply embedded in the operational fabric of its customers operates in a very different economic regime from one whose value can be layered on top of existing infrastructure. When software is cheap to build and AI agents can replicate functionality at marginal cost, the outer layers of the stack become contested territory. The inner core remains more sticky – but not necessarily forever.

2) Pricing Models as Hidden Moats or Liabilities

When investors talk about moats in software, they usually focus on product features, brand strength, customer lock-in, or network effects. Pricing models rarely make the list. They feel secondary, almost cosmetic.

Yet in an AI-driven world, the way a software company charges its customers might be one of the most important predictors of whether it will be disrupted or defended.

At first glance, pricing seems like a purely commercial decision. Seats versus usage. Subscription versus consumption.

Consider seat-based software. For decades, this model was almost synonymous with SaaS success. A company sells licenses to human users, each seat corresponds to a role, and revenue scales with headcount. The model works beautifully in a world where humans do the work and software assists them. But the logic starts to unravel the moment AI agents enter the picture. If an agent can take over part of a workflow previously handled by humans, the number of required seats shrinks. Not overnight, not in a dramatic migration, but gradually, almost imperceptibly.

“Zendesk is a good example. Literally, Zendesk prices seats, and each seat comes with utility. In other words, each seat corresponds to a customer service agent that takes a certain number of customer tickets. So, that company should be worried because I can have an AI agent sit right next to Zendesk and you can slowly siphon off. Instead of paying for 50 Zendesk seats, you can pay for 20, and I can have 30 AI agents sitting next to Zendesk. And that siphoning can happen over time. You don’t have to have an all-in-one decision. It can be a two-way door decision. Those are the most endangered companies in my opinion.”

This is why certain categories of software are structurally exposed. When pricing is tightly coupled to human labor, AI does not need to destroy the product to destroy the economics. It only needs to reduce the amount of human labor that the product supports. That’s essentially the Adobe bear thesis.

By contrast, software whose pricing is anchored in data, outcomes, or system-level functionality behaves very differently. When a platform owns a long-lived dataset or runs a mission-critical process, its value is not easily decomposed into replaceable units. Even if AI agents augment or automate parts of the workflow, the core system remains indispensable. In these cases, the pricing model reflects a deeper form of control: the company is not selling seats, it is selling access to an institutional memory or an operational backbone.

“The companies that are less exposed are ones where the utility is not based on seats, but it’s based on data that has been collected and captured over a period of time. The more timeless the data is, the more protected they are.”

“Somebody uses NetSuite as an ERP. Now, I don’t know how NetSuite actually charges but it doesn’t matter how many seats you buy, the reality is it runs your whole business. And there is no compelling reason for someone to put their career at stake by ripping out NetSuite.”

This distinction helps explain why some software companies feel strangely resilient despite the AI narrative, while others look fragile even if their products are widely used and well-regarded. Fragility is not always about technological inferiority. It is often about economic architecture. A company can have an excellent product and still be vulnerable if its pricing model allows competitors to siphon off value incrementally. Conversely, a company with a less glamorous product can be remarkably durable if its pricing reflects ownership of something that cannot be easily replicated or bypassed.

Now companies could arguably transition their business model from a seat-based to a usage-based model, but Gokul Rajaram argues that this transition would be rather painful and can better be done as a private company:

“For these companies, you need to change your pricing model to be based on outcome, and you need to actually build the product to be based on outcome. It’s easier said than done because literally you’re going from a $20 or $30 per seat to maybe charging a buck, or $0.50 or $0.20 per ticket resolved and you don’t know how that’s going to turn out. So, you’ve got to change your pricing model and I think that’s a very challenging thing. That’s why I think many of them probably need to go private because they have to make this business model transformation in private. I think it’s going to be hard for them to stay public.”

3) Data Half-Life

If pricing models reveal how vulnerable a software business is, data reveals why. Not all data is created equal, and not all data ages at the same speed.

In the age of AI agents, the durability of a software company increasingly depends on the durability of the information it controls.

Some software products generate data that is ephemeral. Messages, tasks, short-term collaboration, transient interactions. This kind of data is useful, but it decays quickly. Its relevance fades, its predictive power erodes, and its strategic value diminishes over time. When AI agents replicate functionality around such products, the underlying data offers little protection. If tomorrow’s system can recreate yesterday’s workflow, there is no deep historical advantage to defend.

Other software platforms accumulate data that behaves more like institutional memory. Financial records, customer histories, supply chain relationships, compliance artifacts, and operational logs are not merely by-products of usage. They are the substance of the organization itself. Replacing a system that holds this data is not just a technical project. It is an existential risk for the company that depends on it.

This distinction explains why some software companies appear almost immune to disruption, even when their technology looks outdated, while others feel precarious despite having modern products and strong user engagement. The key variable is not innovation velocity. It is the half-life of the data embedded in the system.

When data has a long half-life, AI agents struggle to bypass it. They can automate workflows, augment decision-making, and improve interfaces, but they cannot easily reconstruct decades of accumulated records, relationships, and implicit knowledge. The result is a form of structural defensibility that does not show up in feature comparisons or product demos. It shows up in migration friction and organizational risk.

“Well, something like an ERP system, or even Salesforce for sales data and records, those are real customer records. It’s going to be hard.”

By contrast, when data decays quickly, AI agents can compete almost immediately. They do not need to replicate history. They only need to replicate function. Over time, this creates a subtle but powerful shift: value migrates away from the incumbent system toward whatever layer can deliver equivalent outcomes with less dependency on legacy infrastructure.

“Slack, for example, I would say might be in a little bit more precarious state because the data in Slack is not timeless. Half-life is very short.”

For investors, the most relevant question becomes whether data remains valuable across time horizons that matter for customers and organizations. A software company whose data becomes obsolete within months is playing a fundamentally different game from one whose data compounds in relevance over years or decades.

4) The Workflow Depth Test

Every software company operates across two different layers of reality. One layer is data. The other is action.

The system of record (defined in part 1)) defines the first layer. It is where information accumulates over time, where institutional memory is stored, and where organizational truth is encoded. Replacing such a system is difficult because it requires rewriting history. But most disruption does not start there.

Workflow depth belongs to the second layer. It describes how deeply a product is embedded in the way decisions are made and work is executed on top of that data. Some products automate narrow tasks. Others coordinate complex chains of logic, approvals, exceptions, and organizational behavior. The difference determines whether an AI agent can meaningfully replicate the product without rebuilding the underlying operating logic of the organization.

“Second, you want to target a high-value workflow. You want to target a workflow that is deep, that is complex, and that requires custom data.”

In the early era of enterprise software, most products were tools for humans. They supported workflows but did not fundamentally perform them. AI changes this relationship. Once software becomes agentic (alluedd to in part 2)), it no longer merely assists workflows. It begins to execute them. This is why disruption rarely begins with systems of record. It begins with straightforward workflows that touch those systems – repetitive, rule-based, and partially standardized processes that can be automated without forcing companies to rewrite their data infrastructure.

“I think one of the challenges with this whole space is that the models are becoming so good that, if you try to build a company that is light, that is not a hard problem, the foundation model companies are going to eat you.”

From the perspective of AI-native companies, the strategic target is therefore not the system of record itself, but the workflow layer that sits on top of it. By automating a narrow but high-value process, an agent can create immediate economic impact.

This creates a paradox for established software companies. Systems of record are hard to replace, but workflows built on top of them are often surprisingly fragile. The deeper a workflow is entangled with organizational logic, the harder it is to automate. But the shallower and more modular it is, the easier it is to disaggregate. Many SaaS companies built over the past decade sit precisely in this vulnerable middle zone: complex enough to justify subscription pricing, yet modular enough to be peeled apart by agents - one layer at a time?

For investors, the workflow depth test therefore complements, rather than replaces, the system-of-record analysis. The key question is not only whether a company owns critical data. It is also whether the value it captures is inseparable from the execution logic built around that data.

5) Other Structural Advantages?

Up to this point, the framework has focused on software itself: pricing models, data durability, workflow depth. But if AI is making software cheaper to build and easier to replicate, then the most durable companies will increasingly be those whose moats extend beyond software. In other words, the question is no longer whether a product is technically superior. It is whether the business is structurally entangled with realities that software alone cannot easily reproduce.

In the traditional SaaS era, defensibility often came from scale and distribution. In the AI era, those advantages erode more quickly. Models get better. Agents get cheaper. Interfaces get commoditized. What remains difficult to replicate are the things that sit at the intersection of software and the physical, financial, regulatory, or social world.

Some companies achieve durability by embedding themselves in networks that are hard to reconstruct.

Gokul: In the age of AI, stickiness, I think, comes from a few sources. One, you need to have network effects. So, DoorDash is sticky, not just because it has this beautiful app, but it’s because, it’s a network of restaurants, and dashers, and consumers. So you can’t just attack one, you’ve got to go –

Patrick: You can’t vibe code your way to those two.

Others do so by becoming intermediaries for money flows, …

“The second example of stickiness is when you have financial or money moving through you. […] Many of the systems of records, for example, Toast, have payments going through them. And I think that really is interesting because you can’t just start building the point of sale. You also have to have money flowing through it. And I think if you look at the banks, banks are a good example. Once you have something like Mercury, as a business bank, your money flowing through it is hard to then switch because you have regulations and other stuff embedded. So I like things that are a combination of financial services and software because of that.”

… compliance obligations, or actual physical, operational infrastructure:

“The third stickiness is from hardware. You can actually have hardware. Toast is a good example where Toast gives you hardware for free. But if you try to return the hardware, you have to pay them. But either case, the hardware is there. And somebody can’t just build software. They also have to take hardware and put it into the thing and rip out the Toast hardware.”

This helps explain why certain companies feel surprisingly resilient despite intense technological change. Their value proposition is not just functional. It is systemic. Removing them would require rebuilding not only software, but also trust, networks, processes, hardware, legal frameworks, and economic relationships – or a combination of them.

The switching cost is not measured in engineering hours. It is measured in organizational disruption.

“The half-life of software today is so short that unless you have one of these things that make it durable – Hamilton Helmer has this thing called 7 Powers. So you’ve got to have a few of those seven powers that basically are embedded in the business model from day one.”

Putting It All Together: A Disruption Audit Framework for Software Companies

By this point, the contours of a pattern start to emerge.

Systems of record versus surface tools.

Seat-based pricing versus data-based economics.

Timeless data versus ephemeral information.

Deep workflows versus shallow automation.

Durable structural advantages vs. shallow ones.

Individually, these ideas are intuitive. Taken together, they form something more powerful: a method for assessing how vulnerable a software company really is in the age of AI agents.

What makes this method useful is not that it predicts winners and losers with certainty. It does something more valuable: it forces you to abandon the idea that all software businesses belong to the same risk category. Instead of asking whether a company is “AI-proof,” you begin to ask a series of structural questions about where its value actually resides and how easily that value can be peeled away.

The first question is deceptively simple:

What role does the product play in the customer’s organization?

If it sits at the core of operational data and decision-making, disruption becomes costly and politically risky. If it sits on top of existing systems, disruption becomes a matter of convenience rather than survival. The difference between these two positions is often the difference between resilience and fragility.

The second question concerns economic architecture:

Does the company monetize human labor, or does it monetize something that persists independently of headcount?

If revenue scales with seats, features, or usage that AI can automate, the business model is exposed to gradual erosion. If revenue is tied to long-lived data, compliance obligations, or system-level outcomes, the company is operating on more solid ground.

The third question focuses on time:

How long does the value of the company’s data persist?

If yesterday’s information is irrelevant tomorrow, the moat is shallow. If data compounds in relevance over years, disruption requires reconstructing institutional memory, not just building a better interface.

The fourth question examines the topology of workflows:

Can an AI agent replicate the core workflow without replacing the underlying system?

If yes, the company is vulnerable to incremental substitution. If no, challengers face the far harder task of rebuilding an entire stack.

The final question moves beyond software itself:

What non-software structural advantages anchor the business?

Networks, financial rails, hardware deployments, regulatory licenses, and organizational habits all act as invisible fortifications. The more a company depends on these structures, the less likely it is to be displaced by pure software innovation.

Taken together, these questions form a disruption audit, a way of seeing software businesses in multiple dimensions rather than one. Once you apply these concepts, the current turmoil in software stocks begins to look less chaotic. Software stocks are not a homogeneous asset class. Some companies are more fragile not because they are poorly managed, but because their value sits in layers that AI can easily unbundle. Others are likely more durable, not because they are immune to technological change, but because their strengths are rooted in assets that AI struggles to replicate easily.

Conclusion

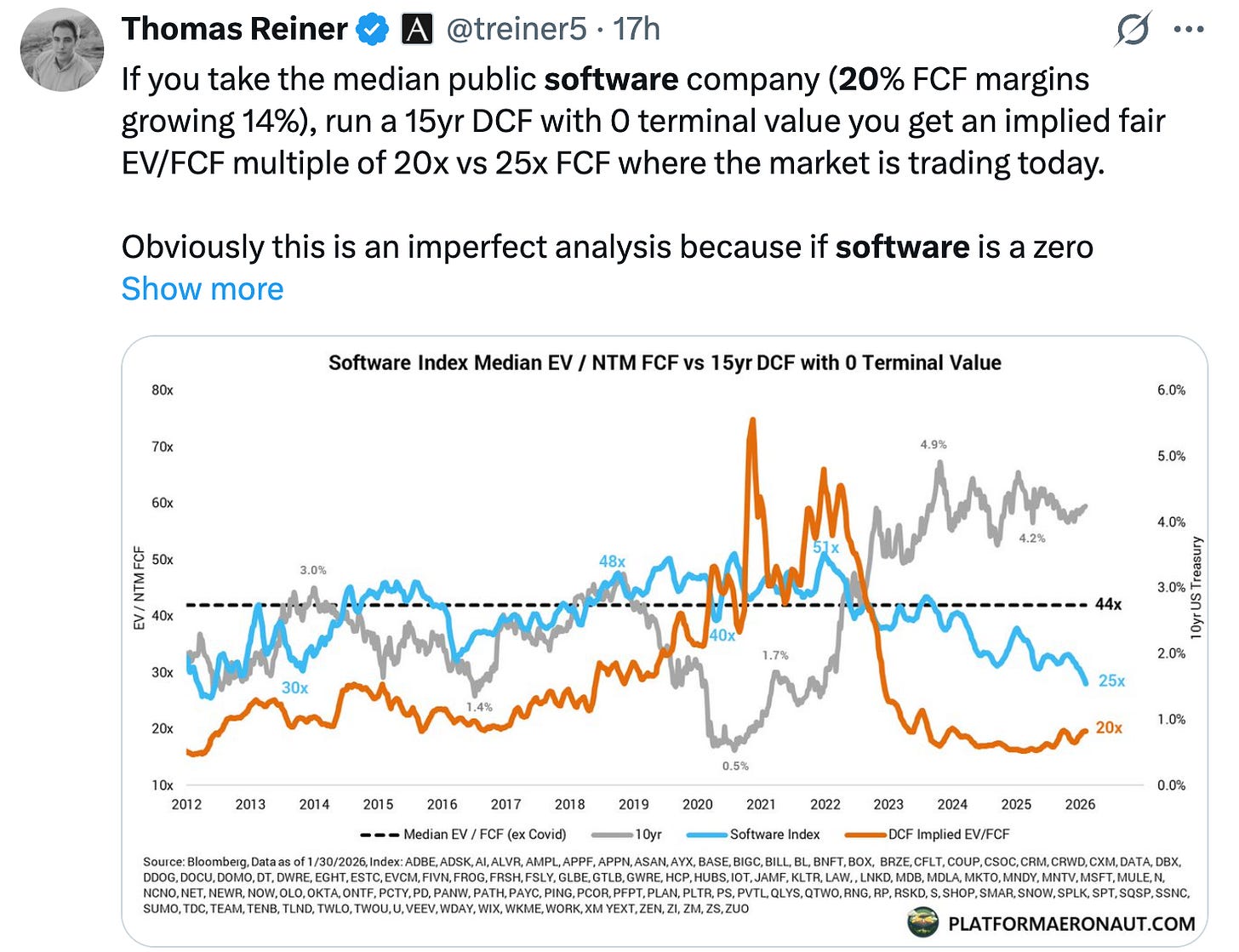

The current sell-off in software feels dramatic, but it is not irrational. AI agents really are changing the tail risk profile of many software stocks. Thomas Reiner highlighted in the tweet below how a business growing 14% over the next 15 years (far exceeding base rates) is “only” worth 20-25x FCF.

I wasn’t sure which discount rate Rainer used, so I just reran the math, and if I apply a 10% discount rate, the intrinsic value is around 20x FCF.

I’ve previously discussed how investors need to be humble enough to acknowledge the exponential rates of improvement we are witnessing. Can you confidently say that software stock X, Y, or Z will still be around 15 years from now?

“There are two big assumptions in this kind of analysis (ie a DCF). There are of course more than two, but I’ll call out two main ones. The first - you are assuming retention rates remain high and stable. You need this to be true in order to predict stable cash flows in that 10 year calculation. If retention rates drop, your cash flows drop precipitously. Second - you are assuming there IS terminal value! Said another way - you are assuming the terminal value is not 0 :) So what’s happening right now? Those two big assumptions are being questioned, which is leading to cratering valuations.“ - Jamin Ball

Why I Sold a Position + The Big "Is Software Still Investable?" Question

I sold a software position last week at a low-teens percentage gain. It was not a core holding, and not the sort of trade that will make or break a portfolio. As I write this, my cash position sits at 7.7%, so this was not about de-risking in some dramatic, all-or-nothing way either – I don’t really do that anyhow.

So again, the selloff doesn’t strike me as completely irrational – especially given the high valuation we were seeing in some software stocks.

What would be irrational is a market treating fundamentally different (software) business models as if they shared the same fate.

Is that the case? In some instances, certainly. However, if we look back at the table I shared in the introduction, you could argue that some of the stocks with the biggest 1-year drawdowns are, according to the framework, those with the least defensible business models in the age of agentic AI (I’m thinking of Wix, Duolingo, Figa).

Once you look at software through the lenses of systems of record, pricing architecture, data half-life, workflow depth, and non-software moats, the sector stops looking homogeneous. Some companies are structurally exposed to incremental value siphoning. Others are protected by deep data gravity, migration friction, and embeddedness in real-world processes. The difference between the two is not subtle, but it is easy to miss if you rely on traditional SaaS metrics alone.

The systems of record vs peripheral software distinction is such a crisp way to think about software vulnerability. I've been struggling to articulate why some SaaS names feel more exposed than others and the data half-life framing explains alot of it. The point about seat-based pricing being structurally vulernable to AI automation is something more investors need to grapple with.

This is good analysis, and I say that as a venture investor who has spent 10+ years investing in b2b software. Some of these are points I needed boning up on.

With that being said, I'll offer one soft counterpoint. Much of what you've shared is good criteria for making an early stage investment, i.e. thinking through whether a $10m ARR company has the goods to grow to $100m and beyond.

When it comes to public SaaS businesses though, particularly those with $1B+ in ARR, I suspect that an outsized portion of these companies have satisfied most/all of these criteria by virtue of not having hit a wall at some earlier point in their lifecycle. (many SaaS companies stop growing for various reasons at $50m ARR, or $200m, or $400m, etc). The companies that made it all the way to public scale have likely developed system or record or quasi-system of record capabilities, multi-product strategies, deep workflows, tons of proprietary data, and significant lock-in in enterprise accounts that are unlikely to ever rip them out.

I'd venture that in the public software universe, particularly those that are still growing at scale, you are probably looking at a basket of the least-disruptable technology companies in the world, at least on average. If they didn't have these key attributes you point out, they'd have been knocked out a long time ago (it's not like AI is the first time there has been substitution pressure on these businesses... the last 10 years have seen insane VC investment into dozens of companies in every single category currently occupied by a current public company).

I guess you can say I'm arguing for a sort of Lindy Effect in software, which is counterintuitive in a field where newer often feels better. But people have been predicting the death of Microsoft since the early 1980s...

I wrote about some of this yesterday: https://thedownround.substack.com/p/its-probably-a-good-time-to-buy-horizontal