Deep Dive: Why Wise’s “Governance Problem” Might Be Its Greatest Strength

Founder Control Isn’t a Flaw – It’s a Feature

So Wise is looking for a new home. Wise is heading west!

(clearly, I wasn’t quite able to generate an accurate image here ;-))

The London-listed fintech darling announced it’s likely shifting its primary listing to the U.S., a move that’s already stirring up its fair share of hot takes.

Among them, Reuters published a short but sharp critique, zeroing in on what they call the “quirky governance” of WISE 0.00%↑ – namely, the fact that CEO and co-founder Kristo Käärmann maintains control through a dual-class share structure, despite holding less than 20% of the tradable Class A stock.

According to Reuters, the smarter move would have been to drop the voting rights and stay in London, where inclusion in the FTSE 100 might have boosted liquidity just as effectively as a U.S. listing.

That argument is tidy. It’s also deeply conventional.

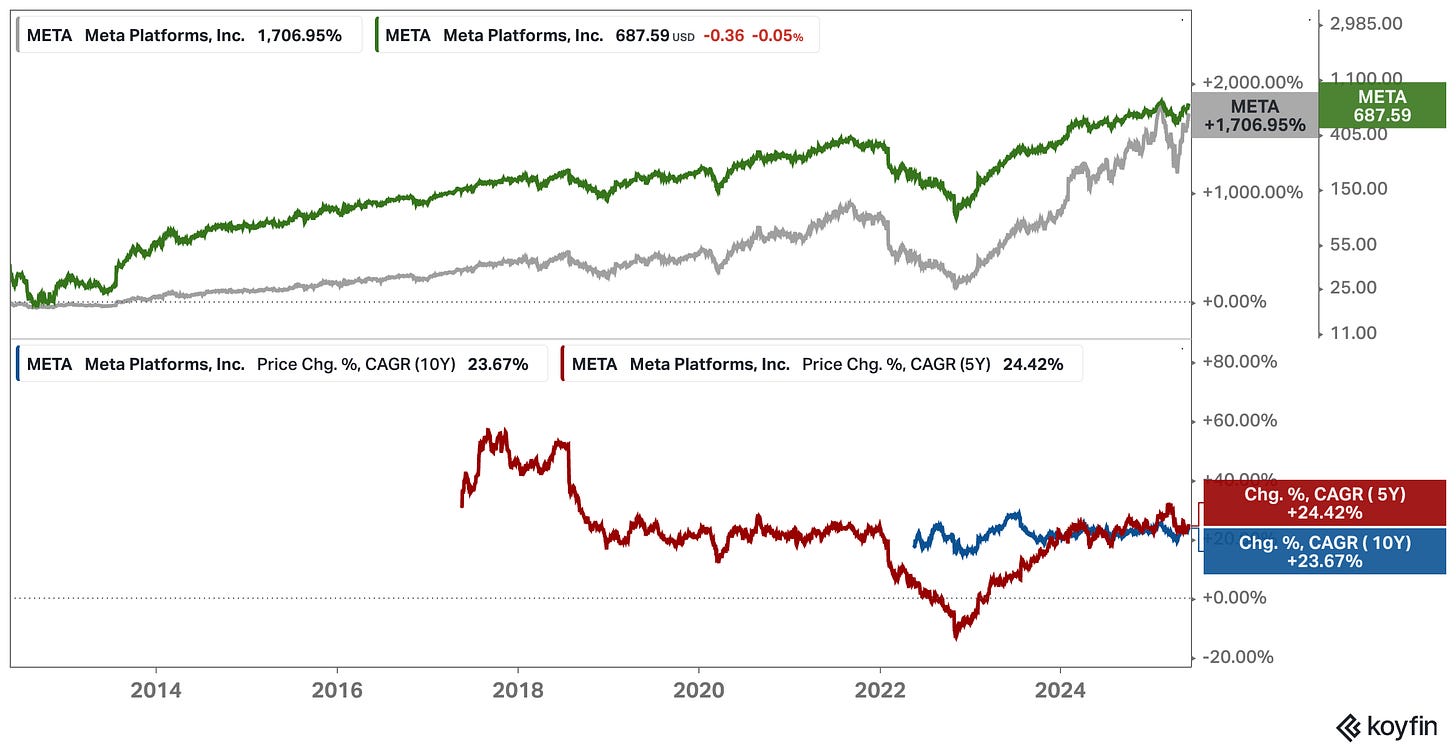

But if you’ve followed founder-led companies for any meaningful stretch of time – if you’ve watched what Mark Zuckerberg has done at Meta, or what Jeff Bezos did at Amazon (Jeff Bezos did not use a dual-class or unorthodox share structure to retain voting control over Amazon, but always was a MAJOR shareholder), or what Patrick and John Collison are doing at Stripe (Stripe does have an unorthodox voting structure that grants the founders outsized voting power relative to their economic ownership) – you start to see how this kind of “governance first” analysis can miss the forest for the trees.

What Reuters is pointing to as a red flag might actually be the core strategic advantage of the business.

Yes, dual-class structures break the traditional mold of shareholder democracy. They skew voting power. They make companies harder to “fix” from the outside. But they also give a founder “space” to think long-term, to make unpopular moves, to trade short-term pain for long-term gain – even when the market is howling for immediate results.

So when I read that Reuters paragraph, I couldn’t help but think of Meta. And I couldn’t help and had to write something up. My second blog post for the day. Yay!

Back to Meta … I wasn’t just thinking of the company, but one specific moment in its history – a moment that might have gone very differently if Zuckerberg had been working under a “clean” governance setup designed to appease index funds and governance consultants.

And it’s in that contrast – between Meta’s mobile pivot and Wise’s structural shift – that we can ask a more interesting question:

What’s the real cost (or benefit) of founder control?

Let’s explore that.

What’s Really Behind the Move? Reuters Voices Criticism!

Earlier today, I published a breakdown of the reasons Wise itself gave for shifting its primary listing to the U.S. You can read it here:

Wise’s FY25 results: The Quiet Compounding Continues

Some businesses just demand your attention. Quarter after quarter, they give you reasons to dive deep – margins wobble, customer growth stalls, strategy shifts. They keep you on your toes.

The company’s press release laid out several justifications: greater alignment with its growing U.S. investor base, enhancing Wise’s profile and reputation in NA, deeper liquidity in American markets, a more tech-savvy peer group, and possibly (?) improved access to capital over the long term (even though it’s extremely unlikely in my view that Wise will dilute shareholders again in the future – they are heading in the opposite direction!).

But that’s not the story everyone’s buying.

Reuters, in particular, published a rather pointed reaction. Their piece doesn’t dwell much on the business logic behind the move. Instead, it pivots quickly to Wise’s governance – and takes a shot that reads like something between a critique and a suggestion:

“Yet Wise needn’t cross the Atlantic Ocean to boost liquidity. One possible obstacle to winning more investors at home is the company’s quirky governance, where Class B owners have nine votes per share. The effect is that Käärmann has a tight grip on the company despite owning less than 20% of the tradable Class A stock, according to LSEG data.”

Translation: this isn’t about liquidity or strategic alignment. This is about control. And specifically, about the fact that Kristo Käärmann, despite owning only a minority of the company’s economic interest, retains majority voting power through a dual-class structure.

Reuters goes on to propose an alternative:

“The alternative to hopping across the pond would be to get rid of some of the CEO’s special rights, which could in turn smooth Wise’s entry into Britain’s main stock benchmark, the FTSE 100 Index.”

In other words, if Käärmann just loosened his grip, Wise could get into the FTSE 100 – and with that, potentially unlock the very liquidity it says it’s chasing in the U.S.

To round out the argument, Reuters adds a little market data for effect:

“That would boost liquidity to U.S. levels: LSEG research found that, relative to the volume of companies’ tradable shares, FTSE 100 trading levels were slightly higher than in the S&P 500 Index in 2022.”

It’s a neat little case: drop the voting rights, stay in London, get FTSE inclusion, and enjoy the liquidity benefits without the hassle of a transatlantic move. Clean. Logical. Shareholder-friendly.

But also – I would argue – oversimplified!

This kind of critique reflects a narrow, almost mechanical view of capital markets. It assumes that governance structures should be optimized for index eligibility, that founders with special rights are inherently problematic, and that the U.S. is only attractive because of its trading volumes.

What it misses entirely is the strategic intent behind founder control – and what can be unlocked when a founder has the power (and runway) to take long-term bets!

If you look at Wise purely through the lens of voting rights and stock indices, you might see a corporate governance anomaly. But if you zoom out, you might see something else entirely: a founder still building, still owning the vision, and not willing to outsource it to the quarterly whims of institutional investors.

“We're thinking about these listing updates very much in the long term, so in the next ten years. And the strategic impact, we expect to be soft and indirect. So there's no one thing that we can can't do today and we can do then. But it we expect this to raise our profile in the largest market of the world. And where our opportunity is is enormous. Already, I'll I'll skip the stats, but a a vast amount of our volumes touch the US dollar as one leg or one currency. So it is important for us to operate in the US. It's a big part of our business already.“ - Kristo Käärmann during today’s earnings call

To understand why that matters, we need to turn to a company that’s already lived through this tension. And it starts with one of the most controversial, and consequential, founder-controlled companies of our time: Meta.

The Zuckerberg Case Study: Founder Control in Action

Meta has long been a lightning rod in corporate governance debates, and much of that stems from one simple fact: Mark Zuckerberg cannot be fired. Not by the board. Not by activist investors.

Thanks to Meta’s dual-class structure, Zuckerberg controls the voting shares, even though his economic stake has gradually diluted over time. For governance purists, that’s a problem. But for those who believe in long-term vision, it might just be the reason Meta is what it is today and has produced the spectacular returns long-term shareholders could enjoy.

There’s a moment from Acquired’s massive six-hour Meta episode that captures this tension perfectly – a conversation that dives into how Zuckerberg and his leadership team responded when Facebook was facing one of the most existential threats in its history: the mobile shift.

At the time, Facebook’s desktop platform was still printing money. But mobile usage was exploding, and the team knew that the current ad model – especially the right-side ad column – wouldn’t work on small screens. They had to act. Fast. But pivoting fully to mobile meant deprioritizing desktop revenue, missing quarterly numbers, and abandoning the cash cow that investors were still cheering.

Ben: “They were in the third column. There’s no third column on mobile. What did you do?”

That’s when Sheryl Sandberg stepped in, reflect in one of the most telling quotes in the entire episode.

Ben: “Her comment to us was, oh, we just stopped caring about the right-side ads on desktop. We took every engineering resource we could off of that, and we put it on mobile. We knew we were going to miss the current quarter—I think they missed a lot of quarters right after their IPO—but this was us trading the present for the future. All we cared about was our future.”

Think about what that means. They knowingly sacrificed short-term financial performance to make a long-term product pivot – and more recently, Meta made use of that playbook again fwiw.

And they did it with total conviction, not because the board signed off on a strategy deck, but BECAUSE Zuckerberg had the control to pull the trigger.

David: “If you have a CEO who has a 20-year view and believes deep, deep in his heart that the best is yet to come, and that this is just a temporary problem, and that person controls the company and owns the majority of voting shares, you can withstand things like this. You just better be right.”

And then came the killer line from Sandberg – the kind of thing that only gets said in founder-controlled companies:

Ben: “She said, ‘Well Mark, nobody can fire you, and only you can fire me. If you’re in, I’m in.’ We buckled our seatbelt and we said, here we go.”

That single sentence says more about the upside of founder control than a dozen governance white papers. Without Zuckerberg’s voting power, it’s hard to imagine that kind of clarity, that kind of risk tolerance, ever emerging from a traditional boardroom.

And history speaks for itself. That mobile pivot wasn’t just successful – it was transformational. It made Facebook (now Meta) into the advertising behemoth it became over the next decade. Without that decision, the company might have slowly faded into irrelevance, overtaken by mobile-native competitors.

This is why I find the Reuters critique of Wise’s share structure so shortsighted. They treat founder control as a relic – a governance flaw to be corrected. But Zuckerberg’s control at Meta wasn’t a bug. It was a feature – one that enabled him and Sandberg to ignore the market, ignore the analysts, and do what they believed needed to be done.

You don’t have to agree with every decision Zuckerberg has made to see the value of that kind of control. Sometimes, a founder just has to be able to say, we’re doing this, and not worry about being fired for it.

The Trade-Off: Governance Purity vs. Long-Term Conviction

Here’s the uncomfortable truth for governance purists: there is no perfect system. Every structure is a trade-off.

One-share-one-vote sounds fair. It aligns economic ownership with control. It limits the power of any single individual. But it also opens the door to short-termism, boardroom politics, and a revolving door of CEOs chasing quarterly targets. In that world, bold strategic pivots – like Meta’s mobile bet – are far less likely.

Dual-class structures flip the equation. They concentrate power. They reduce accountability – at least in the traditional sense. But when paired with the right founder, they can create the conditions for long-term thinking that public markets struggle to accommodate.

The control isn’t just about ego. It’s about protecting a vision from the pressures of the next earnings call.

Is that risky? Of course. If the founder is wrong, or drifts, or becomes disconnected from reality, there’s often no mechanism to course-correct. Investors are strapped in for the ride, whether they like it or not. That’s the cost of conviction.

But the upside – when it works – is a company that can think in decades, not quarters.

Betting on the Right Founder

So when investors react to Wise’s structure, the real question shouldn’t be “How many votes does Käärmann have?” It should be:

“Does Käärmann deserve that control?”

That’s where it gets more interesting. Käärmann isn’t as publicly mythologized as a Bezos or a Zuck, but Wise is very much still a founder-led company. He’s been in charge since the earliest days. He lived the pain point that Wise is solving. And under his leadership, the company has become a rare fintech that’s both growing and highly profitable – and, perhaps more impressively, one that actually saves customers real money. Read more about this concept here:

Unpacking Nick Sleep's Robustness Ratio: A Deep Dive into Customer-Centric Moats

Nick Sleep's concept of the "robustness ratio," introduced in his 2005 Nomad Partnership letter, offers a profound lens for assessing a company's competitive advantage.

In FY 2023, Wise estimated it saved customers over £1.5 billion compared to what they would have paid using traditional banks. That kind of value creation – both for customers and for the broader financial system – is not trivial. And it hints at something deeper: a company that’s still very much in builder mode, still obsessed with fixing an old system.

Is Käärmann infallible? Of course not. He’s had his fair share of controversies! But if you're investing in Wise, you're not just buying a ticker or a balance sheet. You're betting on a founder’s ability to keep building, to navigate trade-offs, and to think ten steps ahead, ten years ahead – all while holding onto the wheel.

You don’t have to like the structure. You just have to decide whether you believe in the person it's built around.

So no – I don’t think the dual-class structure is a problem. I think it’s the reason Wise is still Wise.

That doesn’t mean it’s risk-free. Founder control always comes with the chance that the founder goes off course. That’s the trade. But when you find a founder who’s still building like it’s Day 1, who thinks in decades, and who hasn’t lost sight of the problem they set out to solve – that’s not something I want a board to dilute. That’s something I want to bet on.

So while others are looking at Wise and saying, “Why doesn’t he give up some control?”, I find myself thinking the opposite.

Why would he?

PS: Watch Boston Beer’s Jim Cook sharing a similar take on “the purest form of corporate democracy” starting at the 31-minute mark:

Great insights! Thank you

Excellent post Rene!

My mantra is that the most important aspect of investing is the CEO/management

The same company with a different CEO is no longer the same company

I've spoken about that on this MOI Global podcast: https://rockandturner.substack.com/p/moi-global-james-emanuel-interview

Too few people give the management aspect enough thought. Those that do have a huge competitive advantage