[FREE] Build the Portfolio Only You Could Build: Turning Experience Into an Investing Edge

The Hidden Advantage of Seasoned Investors

A good portfolio isn’t just a spreadsheet filled with tickers. It’s a reflection of your thinking, your temperament, your blind spots, and your edge – and perhaps most importantly, your experience.

That might sound obvious at first, but in a world where investors are constantly encouraged to copy proven models, emulate well-known fund managers, or fit their strategy into some predefined style box, it’s easy to lose sight of just how personal this game really is.

Note: The voiceover above is a custom-made, slightly adapted version of the blog post, edited for a smoother and more engaging listening experience. It’s one of the perks available to paid subscribers, as I’m always focused on adding as much value to my subscribers as possible. Enjoy!

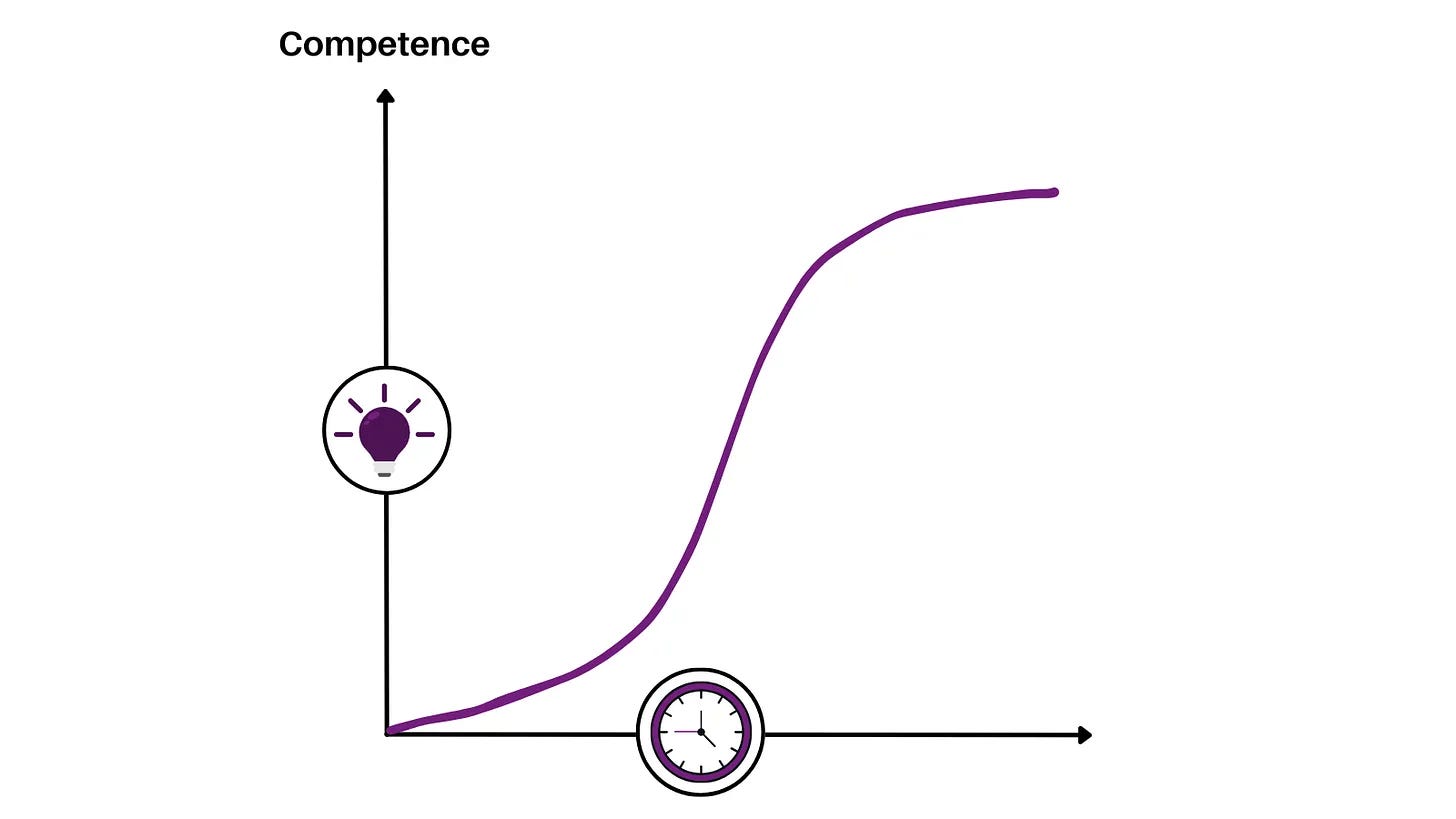

I recently listened to a podcast interview with Ian Cassel (linked further below) where he made a point that stuck with me. He said, in essence, that one of the most underappreciated advantages an experienced investor has is their ability to build a portfolio that reflects the full arc of their investing journey. You start out as a beginner making mistakes, chasing what looks cheap, gravitating toward simple ratios and rules of thumb. Then, slowly, you start layering in nuance. You realize the difference between cheap and undervalued. You start to see what really matters in management analysis. You learn the limitations of valuation tools. And you accumulate a kind of scar-tissue wisdom that just can’t be downloaded or shortcut.

What Ian was getting at is that, over time, this layered experience becomes a kind of Swiss army knife. It gives you optionality. It gives you perspective.

And crucially, it gives you the ability to build a multi-faceted portfolio that isn’t overly reliant on a single sector, factor, or market regime.

That’s a serious edge – especially in a world where things are constantly shifting and arguably shifting more quickly than in the past.

This really resonated with me. Because when I look at how my own portfolio has evolved over the years, I can see this very process unfolding in real time. Early on, I was drawn to deep value names – the optically cheap stocks that seem too good to be true. Over time, I developed more respect for quality, for sustainable competitive advantages, and for the kind of growth that is more durable can compound for years.

I learned to blend intuition with analysis, and to broaden my circle of competence without stretching it.

And I started thinking about portfolio construction not just as a question of what fits together numerically, but what fits together experientially.

In this post, I want to expand on Ian Cassel’s point and offer my own thoughts on what it means to build a portfolio that’s grounded in your experience. Not just your market experience, but your personal intellectual trajectory – what you’ve learned, unlearned, and internalized. I’ll explore how early mistakes can evolve into an investing edge, how to avoid being trapped by a single style or thesis, and how to construct a portfolio that is not only more resilient, but less emotionally taxing.

Ultimately, this is about leaning into what you actually know – not what others say you should know. Let’s dig in.

The Lure of Cheapness and the Limits of Backward-Looking Analysis

Most investors don’t start out with an admiration for high-quality compounders or nuanced frameworks for assessing capital allocation. They start with something more visceral: the thrill of finding a “bargain.” And the market, of course, is more than happy to serve up plenty of what look like bargains (emphasis on “look like”).

It’s an understandable entry point. You're new, you're eager, and you're looking for some sort of anchor in a sea of information. Price-to-earnings ratios, book value multiples, and screens for low valuation metrics offer a sense of control. They give the illusion of objectivity – a way to navigate the chaos with hard numbers. Many of us get seduced by this. I certainly did.

“Cheap” stocks, especially those trading at single-digit earnings multiples, seem like low-risk, high-reward bets. The math looks compelling, the downside appears limited, and there’s a contrarian badge of honor that comes with buying what others are avoiding – I call this “contrarian bias” (or another form of this may be “complexity bias” – a tendency to look for ideas that are overly complex, making you feel smart).

But over time, most serious investors realize that this approach has serious limitations. Multiples are not predictors. They are snapshots of the past. And more often than not, there’s a reason those numbers are so low.

You learn, often the hard way, that stocks trading at 5x earnings aren’t always misunderstood gems. Sometimes they’re value traps. Sometimes they’re businesses in structural decline, or ones with hidden liabilities that don’t show up on a balance sheet. Sometimes they’re being priced correctly, and your thesis – rooted in a reversion to the mean – is the actual mistake.

Tiho Brkan recently made a powerful observation that stuck with me. He said that quantitative analysis, despite being the easiest form of due diligence to perform, often leads to the most errors – especially confirmation bias, recency bias, and a neglect of base rates.

His critique wasn’t aimed at the numbers themselves, but at how investors use them. Backward-looking data is alluring because it feels concrete. But markets are forward-looking and often smarter than you are willing to admit. In my recent piece on the wisdom (and madness) of the crowd I wrote:

“The average market participant today is sharper, better-informed, and more process-driven. And with that, alpha has become harder to generate.“

When the Wisdom of Crowds Turns Mad!

“The longer I invest, the more I come to respect the efficiency of markets.”

Thus, investing, especially in today’s dynamic and often nonlinear environment, demands an ability to reason probabilistically, not just measure what already happened.

Financial statements are easily extrapolated – and that’s exactly what many investors do, often without realizing it. They take a static snapshot and project it forward. But if the company’s competitive landscape is shifting, or if there’s a new entrant, or if the macro environment no longer favors the business model, those numbers are quickly rendered obsolete. And that’s the trap.

Numbers are comfortable. But markets reward insight, not comfort.

This isn’t to say that valuation doesn’t matter. Of course it does. But if you anchor your process entirely on what’s quantifiable, you’re likely to miss what’s meaningful. And early on in your investing life, you don’t always have the experience to know the difference.

What’s interesting is that this stage – the chase for cheapness – often becomes a rite of passage. It’s not a dead end, it’s a stepping stone. You start with multiple-based valuation because it feels like the most accessible lever. But then, if you’re paying attention, the market teaches you that simplicity can be deceptive. That’s when things start to get more interesting…

Beyond Ratios – Developing Real Investing Maturity

There’s a point in every investor’s development where something quietly shifts. You stop asking, “What does my spreadsheet say?” and start asking, “What’s really going on here?”

The transition is subtle at first. You begin to care less about whether a company is trading at 14x earnings versus 18x, and more about whether the business is structurally advantaged, whether it can keep growing without stretching its balance sheet, or whether management is allocating capital like owners or bureaucrats.

That shift marks the beginning of real maturity. You’re no longer impressed by tidy narratives or statistical anomalies. You’re starting to see investing as a probabilistic exercise grounded in real-world complexity. And with that shift comes a much broader view of what it means to be “right.”

You realize that a compelling thesis isn’t built solely on data – it’s built on judgment. You start weighing things that don’t show up neatly in any model: how incentive structures shape behavior, how customer switching costs evolve over time, how capital-light business models outperform through cycles, or how durable competitive advantages look in motion, not in theory.

In short, you learn to think in stories – but not fairy tales. You build narratives that are grounded in reality, tied to observable behaviors, and flexible enough to adapt when conditions change.

And perhaps most importantly, you start to internalize the humility that good investing demands. You’ve seen enough businesses that looked amazing on paper and then blew up. You’ve probably owned a few.

It’s not that valuation stops mattering. It just takes a different role. Instead of being the driver, it becomes a gauge of expectations. You use it to understand what’s priced in.

Maturity in investing doesn’t mean you’ve figured everything out. It means you’ve learned to sit with uncertainty without rushing to simplify it. You develop conviction not from having all the answers, but from knowing which questions actually matter – and which ones don’t.

This evolution is hard to fake. It doesn’t happen because you read the right books or watch the right interviews. It comes from doing – from engaging directly with businesses, from seeing your hypotheses play out in the real world, and from paying close attention to when they don’t.

And this is where things start to compound. Because every mistake, every success, every hard-earned insight becomes a new lens.

You’re not just building knowledge – you’re refining intuition. And over time, that becomes one of the most powerful investing tools you have.

The Swiss Army Knife Advantage – Why Diverse Experience Matters

If there’s one thing the market does consistently, it’s change. Regimes shift. Sentiment swings. The factors that worked last year suddenly stop working. And when you’ve tethered your entire strategy to a narrow style or thesis, those shifts can be brutal.

That’s where experience becomes more than just a collection of war stories. It becomes an asset – a form of adaptive range.

You start to understand investing less as a game of fixed rules and more like a landscape that keeps shifting under your feet.

And what helps you stay upright isn’t dogma or rigid specialization. It’s the breadth of tools you’ve accumulated along the way.

Possessing a Swiss army knife … that’s exactly how it feels when you’ve spent enough years in the market, getting your hands dirty in different industries, market caps, governance setups, and business models.

You start to build this flexible, multi-use toolkit. Not because you set out to collect it – but because the market forced you to adapt.

Early on, maybe you specialized in commodity plays or banks or net-nets. And for a while, that edge worked beautifully.

Until it didn’t.

You realize that even if you’ve mastered a specific niche, macro regimes can leave you stranded for years.

Just ask any deep value investor how the last decade felt as growth stocks crushed everything else.

Cycles can last longer than your patience. And if you’re running outside capital, longer than your client base will tolerate.

That’s where the value of range kicks in. If you’ve studied high-growth tech, but also picked apart insurance companies, if you’ve understood roll-up strategies and also analyzed family-owned industrials, you’re no longer locked into a single playbook.

You have options.

You can build a portfolio that isn't dependent on one narrow factor regime to thrive.

But it goes deeper than that. This type of experience also helps you make fewer false negatives. When you're only fluent in one dialect of investing – say, low P/E stocks, bank stocks, or recurring revenue SaaS – it's easy to dismiss opportunities that don't speak your language. But when you've built up fluency across multiple business archetypes, you start seeing connections others miss. You can appreciate a founder-led microcap and a capital allocator in a mature industry, not because they're the same, but because you know what excellence looks like in both.

And that’s the real edge: pattern recognition at multiple levels of abstraction. Not just recognizing a great ROIC, but understanding why it exists, how durable it is, and how it fits within a much bigger mosaic of economic forces and business incentives.

Building an Emotionally Less Taxing Portfolio

The other benefit? You’re more emotionally resilient. When one part of your portfolio struggles, the rest might hold up. And more importantly, you’re not thrown into existential doubt because you’ve bet the farm on one style. You’ve seen enough to know that everything has a season.

None of this is an argument against specialization. There are investors who go incredibly deep in one niche and outperform spectacularly. But for many of us – especially those managing our own capital – it can be more sustainable, more flexible, and less psychologically draining to operate with range. Not diluted range. Informed range.

That range isn’t something you can manufacture overnight. It’s a function of showing up year after year, learning from wins and losses, and letting your experience shape how you see the world. Over time, that experience adds up to something far more valuable than a clever thesis: perspective.

Constructing a Portfolio That Reflects Your Journey

Once you’ve spent enough time in the markets, you start to realize something: the portfolio you build isn’t just a function of your ideas – it’s a reflection of who you are, what you’ve experienced, and what you’ve learned to trust. And if you’re intentional about it, that personal history can be turned into a real edge.

A lot of portfolio construction advice out there starts from the outside: optimize for Sharpe ratio, blend uncorrelated factors, keep a core and explore around it, and so on.

Some of that may have its place in portfolio construction theory. But what if you start from the inside? From what you know deeply – not just in terms of sectors or geographies, but in terms of business dynamics, management behavior, capital allocation patterns, or even customer psychology?

That’s where things get interesting.

If you’ve spent years studying platform businesses, or have closely followed capital allocators who grow through M&A, or if you’ve had front-row seats to the evolution of a highly regulated industry – why not lean into that? Not to the exclusion of everything else, but as an anchor. Your knowledge didn’t appear out of nowhere. It was earned, shaped by mistakes, by cycles you lived through, by positions you held too long or cut too early.

The key is not just to avoid over-specialization – it's to diversify intelligently based on your cumulative insight.

That might mean mixing business models: pairing recurring revenue software companies from Japan with capital-intensive but defensible infrastructure plays listed in the US. It might mean owning both early S-curve growers with massive TAM ahead and mature compounders that throw off cash and quietly repurchases shares at a 15% yield.It could mean including companies across the market cap spectrum, from micro-caps you’ve studied closely to global brands with decades of durability.

Experience-based construction doesn’t mean abandoning structure. In fact, the deeper your experience, the more discipline you tend to bring. You might let your winners run longer because you’ve seen how costly it is to clip compounding early. You might trim a position not because it’s expensive, but because the underlying assumptions have quietly shifted. These aren’t just portfolio decisions – they’re judgment calls that only experience can sharpen.

And that’s the beauty of this approach. You’re not just diversifying to lower volatility or check a box. You’re diversifying through the lens of what you’ve lived through. That’s what makes the portfolio durable. Not just in performance, but in emotional terms. When you know why each position is in there – not just as a stock, but as a type of business you understand – you're less likely to panic when prices drop. You don’t outsource conviction to price action. You own it.

This doesn’t mean your portfolio has to be complicated. Some of the best investors run focused portfolios with just a handful of names. My friend Andrew just increased one of his positions to a size of 40% at cost because he thinks the downside is a 5% compounded return over the long run (we discussed it in this new podcast episode).

But those names reflect decades of pattern recognition. Each one stands on a foundation of familiarity. It’s not the number of holdings that makes a portfolio sophisticated. It’s the quality and depth of thought behind each position – and the coherence across the whole.

So instead of asking, “What should I own right now?” maybe the better question is: “What does my experience qualify me to understand deeply – and what kind of portfolio does that naturally lead to?” Because the truth is, the market will always test you. But the tests are a little easier to pass when the answers are written in a language you’ve learned to speak fluently.

Conclusion – Build the Portfolio Only You Could Build

Every investor’s journey is unique. The scars you carry, the detours you took, the periods where you had conviction and still got it wrong – they all shape how you see the world. That’s not a flaw. That’s your advantage.

We’re so often told to find our style and stick with it. To define ourselves as growth investors, or value investors, or quality compounder aficionados, or special situations hunters. But the longer you stay in the game, the more you realize that rigid labels start to feel like constraints. They lock you into a narrative that may have served you at one point, but doesn’t reflect where you are now.

What Ian Cassel was pointing to – and what I’ve come to believe more deeply with each passing year – is that your experience doesn’t just make you a better stock picker. It makes you a better portfolio builder.

And that’s not just semantics. A great stock picker can find ideas. A great portfolio builder knows how to weave those ideas into something coherent, resilient, and durable. Something that can withstand not just market volatility, but also regime changes and the psychological toll that comes with it if you “niche” underperforms for 5 years+.

Because let’s face it – investing is hard. Not just technically, but emotionally. Even with the best research and the sharpest analysis, you’ll still have to deal with uncertainty, volatility, and doubt. The more your portfolio reflects your own lived experience, the better equipped you are to navigate those periods. Not because you’ll always be right – you won’t – but because you’ll understand why you own what you own. That “why” is what keeps you grounded when things get noisy.

This doesn’t mean you should ignore new ideas or avoid stepping outside your comfort zone. But it does mean being honest about what you understand best – and leaning into that. It means using your experience not as a crutch, but as a compass. Over time, that compass gets more precise. And if you let it, it can guide you to places no screen or style-box ever could.

So next time you’re thinking about what to add to your portfolio – or whether to change course entirely – take a step back. Not just to look at your holdings, but to look at your history. What have you learned to see clearly? Where have you developed real judgment? What blind spots have you chipped away at over the years?

Answer those questions, and the portfolio almost builds itself.

Not from a template. From experience.