When the Wisdom of Crowds Turns Mad!

Exploring the tension between wisdom and madness in collective decision-making

“The longer I invest, the more I come to respect the efficiency of markets.”

That line, from a blog post by Matt Newell, hit home for me. It’s such a simple statement, but it captures something profound that many investors only come to understand with time and experience.

Early on in my investing journey, I used to think the market was filled with idiots. Now I think it’s filled with people who are mostly... not. And that shift in perspective changes everything.

Here’s the fuller passage that grabbed me [emphasis added]:

“The longer I invest, the more I come to respect the efficiency of the stock market. I think a good chunk of the value investing community is stuck in the past — a past where all an investor needs is the right mindset (buying stocks as if you were buying the whole company; be greedy when others are fearful) and the right approach (good business, good management, reasonable valuation). The past in which Buffett, Lynch and others delivered 25% annual returns for decades on end. I think that time is over, and I doubt it's coming back. Most market participants were fucking boneheads back then. Market participants today are a hell of a lot smarter, and a lot more of them have more of a long-term, fundamental approach. Perhaps not a majority, but it needn't be a majority — only enough to push up the price of the really good stuff.”

That hits hard because it says what a lot of investors may be quietly thinking…

The game has changed. It’s not 1965 anymore. It’s not even 2012. The average market participant today is sharper, better-informed, and more process-driven. And with that, alpha has become harder to generate.

Newell’s “solution” is to lean into microcaps – to go where the market is less efficient, where there’s less coverage, less liquidity, and a better chance to find real informational edges. He writes about companies with no analyst coverage, no institutional ownership, and sometimes virtually no trading volume. And I’m not disagreeing with him here. It’s a compelling approach in a more efficient market environment IF you’re wired for it.

But I’m not.

I Choose a Different Edge

Personally, I attempt to lean into something else: the behavioral edge. Not because I dismiss the informational edge – I respect it deeply – but because I find the risk/reward profile in the microcap space a little too binary for my taste. The trajectory of outcomes tends to be (very) wide, and the average business quality tends to be lower compared to larger-cap companies.

Now, I firmly believe even the world’s LARGEST, most closely followed companies get mispriced. And not just occasionally – it happens all the time!

I’ve written about this before, but I keep returning to a passage Rob Vinall shared in one of his investor letters (see below). It’s one of the most articulate rebuttals to the idea that only small caps can be massively mispriced.

He argues that large- and even mega-cap stocks, while surrounded by round-the-clock coverage and swarms of analysts, can become trapped in consensus narratives that harden into assumptions – price drives narrative. In his own experience, investing in Google during its mobile transition or Facebook amid rising regulatory fear wasn’t about discovering unknown facts – it was about seeing the same facts differently.

Meta’s more recent stock performance may be the best case study to prove his point. The stock is up 7x from the 2022 lows, up 7x over just around 2.5 years, compounding at a triple-digit rate over this period… that reflects some major market inefficiencies (at least when it comes to Meta back in 2022).

When enough people agree on a flawed interpretation, mispricings emerge even in the most visible corners of the market.

That insight has stuck with me. It's not a matter of finding obscure facts – it's a matter of identifying when the dominant interpretation has calcified and detached from reality. That’s where the opportunity lies.

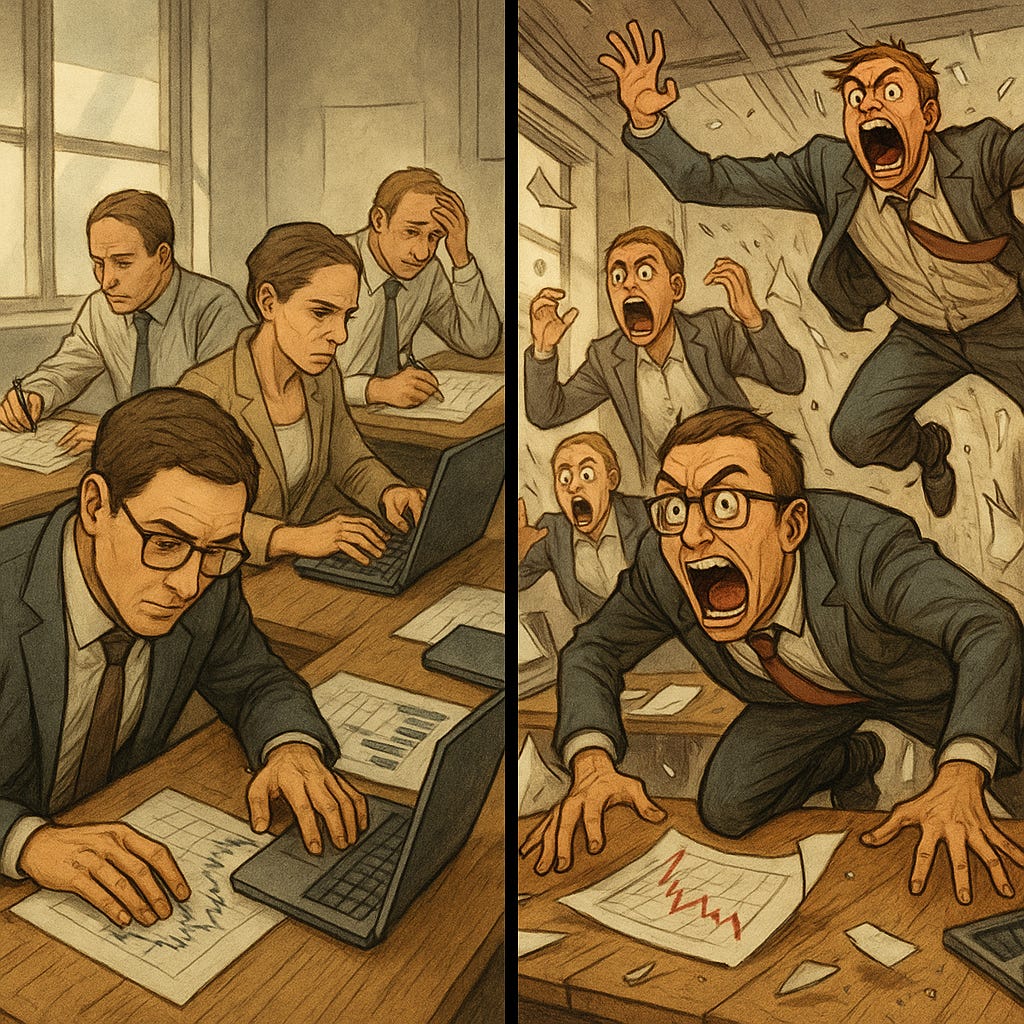

And that brings me to one of the most powerful mental models in investing: the wisdom of crowds – which sometimes break ...

Before we dive back in, a quick note…

Want to compound your knowledge – and your wealth? Compound with René is for investors who think in decades, not headlines. If you’ve found value here, subscribing is the best way to stay in the loop, sharpen your thinking, avoid costly mistakes, and build long-term success – and to show that this kind of long-term, no-hype investing content is valuable.

Thank you for your support!

How Smart Markets Work

Michael Mauboussin has long framed market efficiency through the lens of crowd intelligence. Markets, he argues, function efficiently when three key ingredients are present:

diverse perspectives,

a mechanism for aggregating information (like a stock exchange),

and incentives that reward accuracy and penalize error.

When all three conditions hold, even flawed individuals acting independently can collectively produce remarkably accurate pricing.

The jellybean jar example comes to mind – no single guess is reliable, but the average of many guesses often comes very close to the truth.

But here’s the problem: those conditions don’t always hold.

And the one that tends to fail first is diversity. As soon as people start thinking alike – not just agreeing on outcomes, but using the same mental models, the same inputs, the same narratives – the crowd becomes less of an independent ensemble and more of an echo chamber.

Investors begin standing on the same side of the boat. And that’s when things start to break.

The Fragility of Diversity

What makes this even trickier is that the breakdown is rarely obvious in the moment. Diversity can break down all at once or deteriorate slowly, almost imperceptibly.

Everything may appear stable until one final shift – a sentiment change, a catalyst, a moment of fear – causes a cascade. Other times, the change in sentiment occurs more slowly, but eventually, the crowd shares the same belief.

What’s interesting is that this dynamic doesn’t play out the same way in all market regimes. In bull markets, inefficiencies tend to persist far longer, making it hard to call/time market tops. When prices are rising, narratives are self-reinforcing. The crowd isn’t just optimistic – it becomes increasingly synchronized in its optimism. Dissidents often stay silent or exit the game entirely. There’s no obvious trigger to reset expectations, so valuations and assumptions can drift far from reality, unchecked. That’s how bubbles form – not from a lack of information, but from a temporary breakdown in independent thinking.

Crashes, on the other hand, tend to correct inefficiencies far more quickly – I’m of course generalizing here, but pointing out tendencies. When fear takes over, the market becomes hyper-sensitive to new information, even if that information is incomplete or misunderstood. Correlation spikes. People sell first and ask questions later. Prices overshoot to the downside, not because the facts have changed drastically, but because the wisdom of the crowd has morphed into something more primal.

This idea of fragility shows up in systems beyond markets. In ecology, losing species diversity may not show any visible effects for years – until a small change triggers a rapid collapse. Markets can behave the same way. For long stretches, prices appear rational, signals consistent, volatility low. But underneath the surface, everyone may be anchoring to the same assumptions, chasing the same trades, pricing off the same models.

What I Look For

Inefficiencies show up when that crowd wisdom fractures and the madness takes over. And that happens in different ways: company-specific panics following a single earnings miss or a shorter-term challenge that creates uncertainty, industry-wide fear cycles where entire sectors become untouchable, or market-wide selloffs where risk aversion becomes indiscriminate. Those are the moments I try to exploit. Not with bravado, not with the assumption that I’m smarter than everyone else, but with the willingness to remain rational when others are letting go of the wheel.

In those instances, sentiment detaches from business reality. Expectations compress beyond what is likely or reasonable. And that’s where the behavioral edge shines – if you can stay grounded.

But you still need discipline. Being contrarian alone isn’t enough. You need the calculator too – the valuation discipline, the business analysis, the probabilistic thinking.

That’s why Seth Klarman’s formulation continues to resonate: value investing is the marriage of a contrarian streak and a calculator. If you don’t have both, you’re either reckless or irrelevant.

“Value investing is at its core the marriage of a contrarian streak and a calculator.“ - Klarman

The Job of the Rational Investor

So what’s our job as an investor? I’d argue it’s two-fold. First, learn to read the crowd. That doesn’t mean dismissing the market’s opinion. Most of the time, it’s right. Markets, when functioning properly, are breathtakingly efficient. Respect that efficiency. But sometimes they aren’t. And your job is to understand when the conditions that make them wise have started to falter.

Second, stay patient. Because those moments are rare. But when they come – when the chorus becomes too loud, when uncertainty gets priced like doom, when good businesses are being dumped simply because they’re associated with a narrative people want to flee – that’s when you step in. Not because you know something no one else does. But because you’ve stayed calm, considered the long-term prospects, kept your edge, and waited for the crowd to lose theirs.

That’s where the opportunity lives for me. Not in obscure corners of the market. Not in complexity for complexity’s sake. But in moments of temporary madness – when a smart system briefly forgets how to think.

Before you move on to read the next piece:

Want to invest in the one edge that compounds forever? Join hundreds of investors sharpening their thinking, avoiding mistakes, and discovering quality before the crowd. Subscribe to Mental Models Wealth Building and build the portfolio behind the portfolio.

Really nice read!

I couldn't agree less with Matt Newell's view point.

Before the internet, most investors were professionals - doing research the old-fashioned way - active investors dominated and stock picking was the order of the day.

Fast-forward to today:

(1) passive investing is now the dominant form (that's dumb money - capitalism used to channel capital to where it could be used most productively - that is no longer the case - market efficiency has been torpedoed)

(2) every man and his dog now thinks he is Warren Buffett - Robin Hood and other platforms enable cheap and easy access to the market - most of these people don't have a clue - the stock market has become a casino for many

(3) social media has created a situation where hype drives markets more than fundamentals - fake news and false narratives drive the market

(4) stock based compensation has spiraled out of control and companies buying their own over inflated stock to offset dilution is amplifying dislocations between intrinsic value and market price

(5) loose monetary policy for 15 years - the ZIRP era - created an everything bubble which created an illusion that markets only go one way. Suddenly every retail investor thought they had cracked the code - the day of reckoning is coming when the young generation experience their first proper draw down

Do you still think that the market is more efficient today than it was several decades ago?