Deep Dive: Revisiting Uber ($UBER)

Uber vs. AVs: Platform King or Obsolete Middleman? – Why the AV Debate Starts with the Wrong Question

Uber’s stock has had a remarkable run over the past few years, but the narrative has become less straightforward lately. After peaking near the high-$90s in late 2025, the stock has pulled back by roughly 15–20 percent in recent weeks, and now trades around the low-$80s.

That retracement is not dramatic in isolation, but it is telling. It suggests that the sentiment has shifted again slighty, and the market is no longer pricing Uber as a simple growth compounder. Instead, investors are increasingly forced to confront a deeper question:

What does Uber actually become in a world where autonomous vehicles move from science fiction to commercial reality? And if Google and Tesla become the dominant incumbents with defensible moats, is there still need for an aggregator

Rose Celine Investments raised the bear case on X in early January:

“Everyone keeps repeating the same aggregated demand argument and I understand why, because for a long time it was obviously true. $UBER owned demand, riders opened $UBER first, drivers were fragmented, and whoever controlled demand basically controlled the whole system.

That worked really well in a human driver world and it explains why $UBER became what it became. The problem is people are taking that exact same logic and just extending it forward without really stopping to think about what actually changes once autonomy becomes scaled. […]If you own the cars and you’ve spent tens of billions building them and the entire ecosystem, are you really going to accept paying 20% forever just to ‘rent’ demand? And more importantly, after spending such a massive amount of capital are you going to accept $UBER coming back later and demanding 30% instead of 20% because they ‘own demand’?”

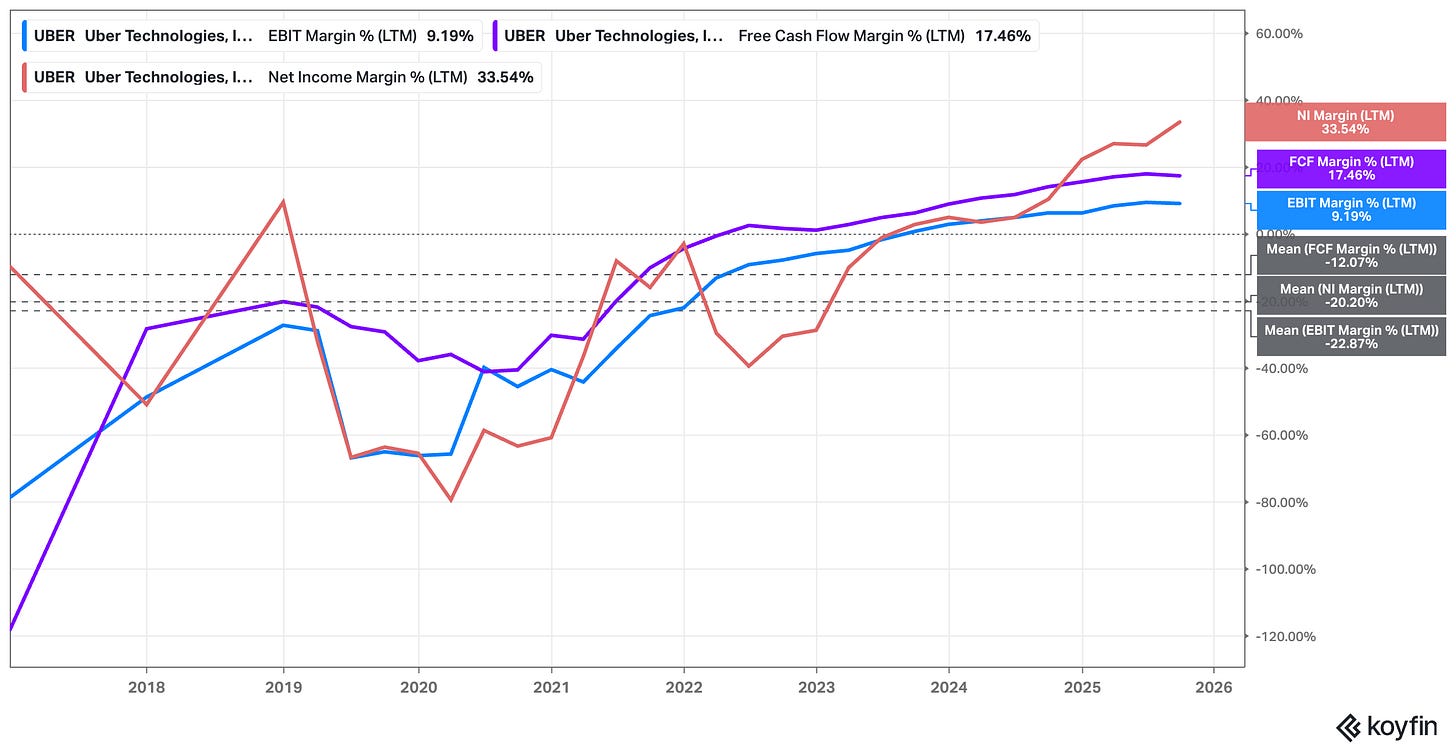

At a fundamental level, Uber’s operating performance has rarely looked stronger. Over the trailing twelve months, the company generated roughly $49.6 billion in revenue, about $4.6 billion in EBIT and around $8.7 billion in free cash flow (the FCF metric needs some major adjustments, though; we will discuss this in this analysis further below).

Margins have structurally improved compared to the past and the bull case argues that Uber only just started flexing its operating leverage and that there’s more upside on the profitability side: EBIT margins sit near 9 percent, free cash flow margins around 17 percent, and net income margins are elevated, partly due to one-off effects but still indicative of a business that has moved decisively out of its loss-making phase. Growth has not disappeared either.

Revenue has compounded at more than 35 percent annually over the past five years and still grew at roughly 18 percent over the last year. Other KPIs are also trending in the right direction: up!

The valuation picture reflects this duality. On a forward basis, Uber trades at roughly 20x next-twelve-month earnings, around 22x forward EV/EBIT, and just under 20x price-to-free-cash-flow. On trailing metrics, multiples look even lower, with a P/E near 10x and EV/EBIT below 40x.

If anything, these numbers suggest a market that is struggling to reconcile two opposing forces:

a business that is scaling, monetising, and generating cash at increasing rates, and …

a structural uncertainty about whether its role in the mobility ecosystem will expand or erode over the next decade+.

That tension is what makes Uber such a fascinating investment case right now. On the surface, the story looks almost too clean, the stock too cheap given its runway, embedded operating leverage, and user base. A global platform with hundreds of millions of users, improving margins, strong free cash flow, and multiple growth vectors across mobility, delivery, and local commerce.

But beneath that surface sits a more uncomfortable layer of questions that the market is clearly beginning to price in:

If autonomous fleets scale meaningfully, who captures the economics of mobility?

Do AV operators eventually bypass intermediaries like Uber, or do they end up relying on them even more?

Does Uber’s network advantage strengthen in a fragmented autonomous world, or does it weaken once a few players reach “good enough” scale?

How does leverage shift across geographies, where network effects are hyperlocal rather than global?

And ultimately, is Uber’s current valuation optically cheap because the market is missing something – or because it is correctly discounting a future where the company’s take rate and strategic relevance are far less secure than they appear today?

How should Uber investors think about Google’s 2.2 billion MAU distribution advantage?

Also, which adjustments do we have to make to arrive at “true free cash flow” and how attractive is the current valuation?

These are not abstract questions. They sit at the intersection of technology, economics, and consumer behaviour. And they are exactly what I want to unpack in the analysis that follows.

Link to my initital analysis:

Why the AV Debate Starts with the Wrong Question

The debate around Uber in an autonomous-vehicle-dominated world is often framed as a contest between capital and demand. Autonomous fleet operators invest tens and tens of billions into vehicles, infrastructure, and AI stacks. Uber, in contrast, owns no fleets at scale and sits between supply and consumers. The intuitive conclusion is that the capital-intensive side should ultimately hold the leverage. After all, why would a company that spent enormous sums building autonomous fleets permanently hand over 20 percent of its revenue to a middleman?

I think this framing is intellectually coherent but incomplete. It implicitly centers capital providers rather than end consumers. Yet in most platform markets, leverage does not accrue to whoever spent the most money. It accrues to whoever controls the consumer’s default choice. Consumers do not care how much capital was required to build a system. In the app-based ridesharing space specifically, they care about thee things primarily:

how fast a ride arrives,

how reliable it is, and

how much it costs.

If those conditions are satisfied, the underlying ownership structure becomes almost irrelevant from the user’s perspective.

“So in focusing on the sparse geographies, we’re really focused on three areas. It is on the expanding the availability of the product, increasing the reliability of the product, and then ensuring that we have the right product fit.

So for example, the wait and save product has been an excellent match for the sparse geographies because typically when you’re in a more suburban environment, you’re in a situation where you don’t mind waiting a little bit for your ride, which gives us the ability to find the right match and to compensate for the lower density of cars which may be in that market. So all of that is continuing to feed the flywheel, and we feel very excited about how sparse geographies are going to continue to provide growth for our U.S. market for many quarters to come.” - CFO Prashanth Mahendra-Rajah - Q3 call

Mobility makes this dynamic unusually brutal because switching costs are close to zero. Downloading another app takes seconds. Payment methods can be stored instantly – take you about five minutes or less. Users can compare wait times and prices with minimal friction.

In network theory, this is a textbook case of multi-tenanting: users participate in multiple networks simultaneously. When multi-tenanting is easy and credible substitutes exist, sustained margins above the cost of capital tend to be competed away unless strong barriers exist. If one autonomous fleet operator consistently earns extraordinary margins per ride, rivals have incentives to undercut pricing or improve service until those margins compress.

This is why the “fleet operators will dominate” narrative cannot be evaluated purely through the lens of capital intensity. Capital expenditure does gives companies some degree of leverage, but it does not automatically lead to switching costs and translate into pricing power. Pricing power emerges from consumers unable to switch, or more broadly, consumer preference. And consumer preference in mobility, or so I would argue, is narrow, pragmatic, and fickle.

Hence, Uber’s current scale matters in this context, because it shapes consumer habits. In Q3 2025, Uber reported 189 million monthly active platform consumers, 3.5 billion trips, and $49.7 billion in gross bookings, with trips up 22 percent year-over-year and adjusted EBITDA up 33 percent.

These are not the metrics of a platform in decline. They are the metrics of a marketplace still expanding at scale.

At the same time, management is explicit that the company’s strategic focus is shifting from single transactions to long-term relationships. As Dara Khosrowshahi put it, Uber is moving “from Trip experience to Lifetime experience,” deepening engagement across its platform and increasing cross-product usage.

“We’re deepening engagement across our platform with cross-platform consumers spend three times more and retaining 35% better than single product users.“

The real battleground is fighting for consumer mindshare; shaping consumer behavior.

Network Effect Characteristics

There is another layer often overlooked in the leverage debate: network effects in mobility are hyperlocal. A dense fleet in one city does not automatically translate into dominance elsewhere. Regulatory environments, road infrastructure, weather, labor markets, and consumer preferences differ sharply across geographies.

Uber itself acknowledges that growth dynamics vary by market, with sparse geographies expanding faster than dense urban centers and still far from saturation.

“So the sparse geography strategy, which we had talked about this originally, if you recall, this originally was an output of the work that we had led on focusing on how to increase our Delivery business. And in that analysis, and as we began to look at how we can make better progress on Delivery, we identified that there was more opportunity for us to continue to push on sparse geographies in the Mobility area. And the benefit that we’re seeing there really is first, it’s a very large footprint. So as we look across the globe here and similar for the U.S. our sparse geographies are actually growing at about 1.5x the rate of our denser market, and the penetration opportunity in these sparser markets continues to be quite high. We -- our rough take is that we’re maybe 20% into what the opportunity is on the sparse market. So still lots of upside there.” - CFO Prashanth Mahendra-Rajah - Q3 call

This means that leverage of the fleet providers – if it will be material in the first place – will not be global and uniform. It will be local and conditional. I find it very unlikely that Uber will go out of business entirely.

Once you accept that premise, the question stops being …

“Does Uber win or lose in an AV world?”

… and becomes …

“Under what conditions does Uber remain the default interface in each local market, and under what conditions do autonomous fleet operators bypass it?”

That is where the economics start to get interesting.

When Aggregators Matter – and When Not … + A Nuanced Look at the Nvidia Partnership

The value of an aggregator is not constant. It rises with fragmentation and falls with consolidation. We discussed this in our Trainride analysis.

Imagine a city with two autonomous fleet operators. Comparing prices and wait times across two apps is manageable. Add a third operator, and friction increases. Add five or six, and manual comparison becomes annoying enough that users start looking for a single interface that abstracts complexity away by … you guessed it: aggregating supply and data.