This year has been unusual for me as an investor. Not because of volatility or a big macro call – but because I’ve turned over more of my portfolio than I’d usually like. I’m someone who tries to let intrinsic value compounding do the heavy lifting. So ideally, portfolio changes are rare, thoughtful, and tied to meaningful shifts in fundamentals or valuation (or both).

But this year? My portfolio activity has been far more active than usual. The turnover rate is higher than my typical rhythm, and it’s not something I want to make a habit of. That said, I do think the decisions I’ve made were grounded in sound reasoning. They weren’t driven by noise or emotions – they were tied to changing opportunity sets, evolving capital allocation dynamics, and a more refined view of long-term risk and return.

The most dramatic move? I sold my entire position in Meta – a stock that’s been my single largest winner over the last few years, both in absolute and relative terms. That wasn’t an easy call. It forced me to reassess not only my conviction in the business, but also how I think about capital allocation, valuation asymmetry, and portfolio fragility at large positions.

But this isn’t just a story about Meta. It’s also a story about what I’m reallocating into – and why. It’s about betting on asymmetry. It’s about holding some cash when the opportunity set doesn’t scream at you. And it’s about shifting the portfolio’s center of gravity away from the U.S., not because I’ve lost faith in American business, but because I think global diversification has become a more rational default.

So in this post, I want to unpack the thinking behind this active portfolio season. We’ll cover:

Why I sold Meta, despite it being my biggest and most successful position

How Meta’s capital allocation decisions changed my risk/reward calculus

Why I believe their massive AI capex push introduces reinvestment fragility

What expected returns look like at current Meta valuations – and why that matters

Why I’m deploying capital into other stocks, and how I think about upside asymmetry

How I’m weighing valuation, quality, and expected return in today’s opportunity set

Why my portfolio is now more exposed to Europe than the U.S. – and what’s behind that shift

Before we dive back in, a quick note…

Want to compound your knowledge – and your wealth? Compound with René is for investors who think in decades, not headlines. If you’ve found value here, subscribing is the best way to stay in the loop, sharpen your thinking, avoid costly mistakes, and build long-term success – and to show that this kind of long-term, no-hype investing content is valuable.

The Meta Sale – My Best Performer, but Time to Move On

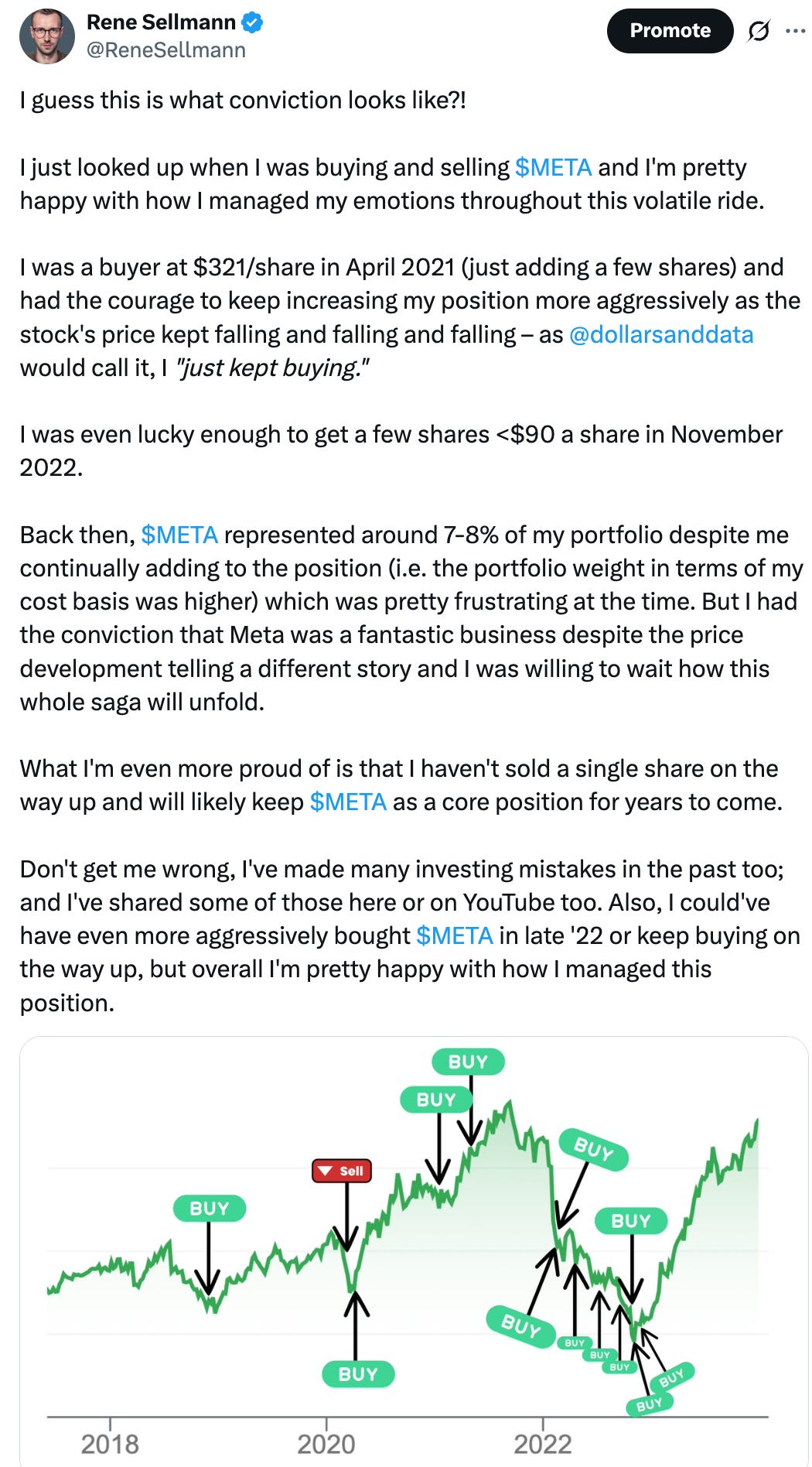

Selling Meta was not a decision I took lightly. It’s been, without a doubt, the best investment I’ve ever made in absolute terms. There were quarters where Meta alone made the difference in my overall performance. For most of the past twelve months, it hovered around a 30% portfolio weight – sometimes even exceeding that threshold despite me consistently adding to other positions. That’s not just conviction. That’s concentration.

And it paid off. Meta’s transformation story – from the post-Apple IDFA hangover to Reality Labs CapEx, and then its resurgence through ruthless efficiency and a renewed AI narrative – delivered tremendous shareholder value. So why sell now?

Let me be honest: I wrestled with this for months. I trimmed the position earlier this year by about 30% in two tranches, but I held onto the core. A big reason was taxes. The capital gains hit would be substantial – and mentally, that felt like a brake on my decision-making.

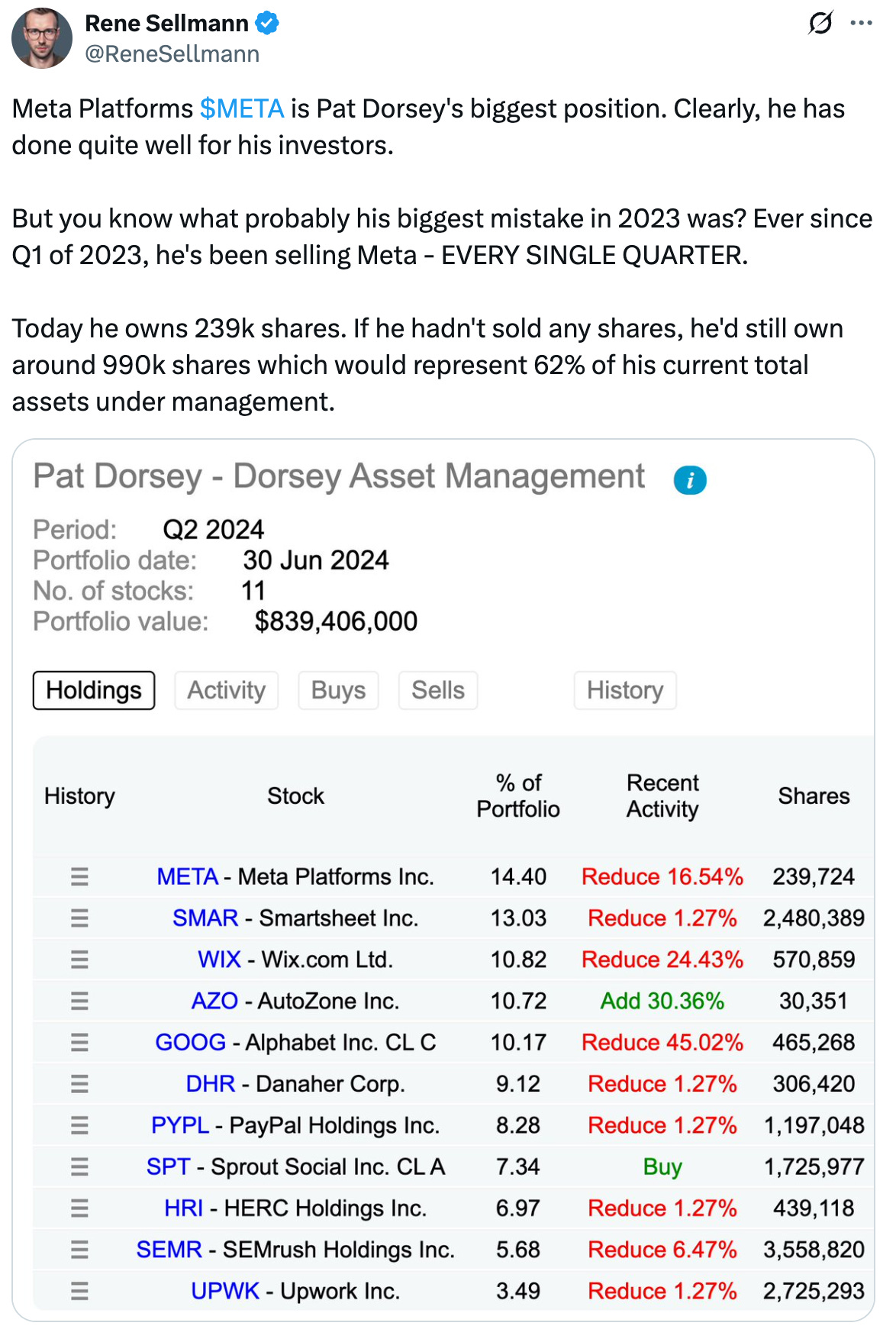

Another reason? Call it cognitive dissonance. I had publicly criticized other investors, like Pat Dorsey, for trimming their Meta exposure too early. Just last August, I posted a thread highlighting how Pat had reduced his Meta stake every quarter since Q1 2023. At the time, I argued that if he’d simply held, he’d still own nearly a million shares, and Meta would represent 62% of his AUM.

But Meta is also up another 40% since I wrote that – imagine Dorsey not selling a single share until today.

And yet, I’ve now fully exited the position.

This wasn’t about losing faith in the business. If anything, I still believe Meta is one of the best businesses in the world. It may very well be a much more valuable company ten years from now. I even wrote a post not long ago with the tongue-in-cheek title “Meta’s Path to a $10 Trillion Market Cap: A Bold Thought Experiment?” And I stand by the core thesis – Meta could get there under the right circumstances – but I’m less certain about the path Meta will follow in the AI race.

Meta's Path to a $10 Trillion Market Capitalization: A Bold Thought Experiment?

Unlike some of my peers, I rarely focus on labeling stocks with grandiose labels such as "This is the next 10x stock!" or even "A stock with 100x potential.!"

Something shifted. Actually, several things did. And once I started stacking them, the sell decision became more rational – even if it remained emotionally difficult.

First, there was capital allocation. I’ll get into the AI capex math in the next section, but the short version is this: Meta’s recent spending spree doesn’t inspire confidence. Not because they’re investing in AI – that part makes sense strategically – but because of the scale, the speed, and the fragility of the returns.

Second, there’s founder risk. This is where Tiho Brkan’s perspective really resonated with me. He’s been vocal about how Meta’s single-threaded reliance on advertising revenue, combined with Zuckerberg’s “all-in” style, introduces a form of fragility that most investors underestimate. His analogy of fragility versus risk stuck with me. Risk, he argues, can be managed or mitigated. It’s like driving through fog – you slow down, you increase your margin of safety. Fragility, on the other hand, is structural. It’s like an old bridge that still carries traffic – until one day, a single truck collapses it. When Tiho talks about Meta, he’s not just pointing to competition or regulation. He’s pointing to that structural fragility that comes from betting the entire strategic direction of a trillion-dollar company on one man’s conviction.

Two years ago, Zuck was 100% convinced the metaverse was the future. He changed the company’s name, poured billions into Reality Labs, and asked investors to trust his vision. That didn’t pan out – at least not yet. Now, he’s equally convinced AI is the future. Again, he’s not hedging. He’s going all-in. Tiho’s point is not that Zuck will fail. It’s that this binary, all-or-nothing approach doesn’t leave much room for error. And when the scale of the bets is $70 billion in capex annually, the consequences of misjudgment are magnified – especially if Meta represents your largest holding.

This is in stark contrast to other great capital allocators. Buffett, Bezos, or even Satya Nadella have all made bold bets, but rarely have they staked the entire narrative of their companies on one initiative. Zuck’s approach, while visionary, carries a kind of fragility that, maybe from Meta’s point of view, is even necessary. It may be the rational thing to do to finally reduce platform dependency. But that doesn’t mean that holding onto Meta in size is the rational thing to do for investors considering the opportunity set available to them.

And lastly, there’s opportunity cost. Meta is no longer cheap. It trades at around 28x next-twelve-month earnings, 34x trailing free cash flow, and over 50x if you adjust for stock-based comp. I suspect the SBC-adjusted multiple won’t come down anytime soon, considering Zuck’s ambition to attract the best AI talent out there. And SBC is a very real cost. You cannot deny that. The same can maybe be said about the CapEx. I long-believed Meta’s steady-state margin is structurally higher than LTM numbers would suggest. But today, I’m not so sure what portion of the massive CapEx is actually maintenance-related and how much is pure growth investment.

That doesn’t mean the stock is wildly overvalued – but the future return profile isn’t screaming attractive either. At these multiples, most of the heavy lifting for future returns has to come from topline growth and margin expansion. That’s doable, but it’s also where execution risk starts to matter a lot more.

In contrast, I’m now finding ideas – admittedly lower quality businesses – that are trading at 10x earnings with double-digit growth potential and some re-rating optionality. If those stocks re-rate even modestly while compounding earnings, the forward return math starts to look a lot better than Meta’s from here.

So yes, I sold Meta. Maybe too early. Either way, I think it was the right decision given what I know today – not what I hope will happen.

But to understand the real reason this call tipped over from “hold” to “sell,” we need to talk about capital allocation, return hurdles, and why Meta’s AI investment cycle feels structurally different from the ones that came before.

Capital Allocation and AI – Why I’m Wary of Meta’s $70B Bet

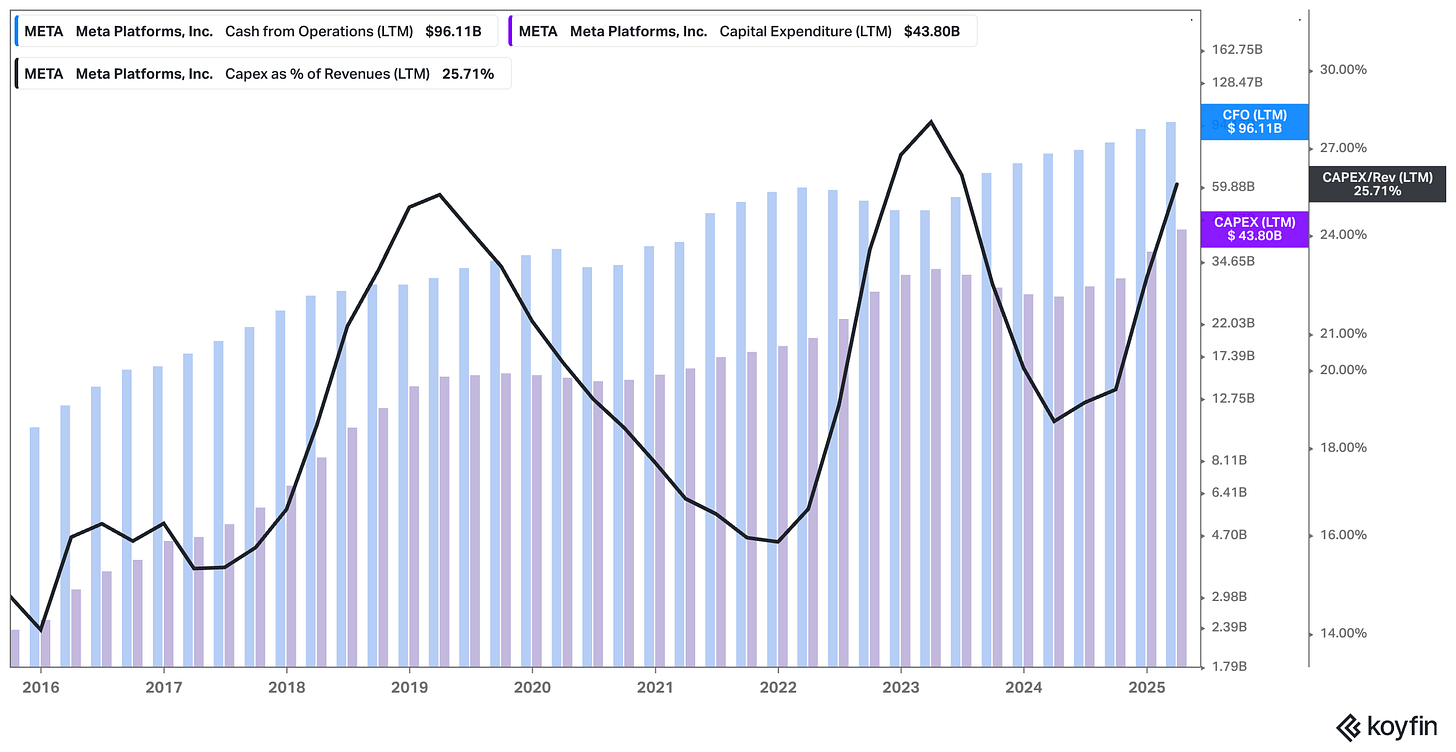

If there’s one thing that finally tipped my decision to sell Meta, it’s this: capital allocation. More specifically, how Meta is choosing to spend its enormous cash flows at this point in its lifecycle. When I say “enormous,” I mean it. We’re talking about a company that generated around $52 billion in free cash flow over the last twelve months.

And instead of letting that capital flow back to shareholders or carefully deploying it into high-confidence growth initiatives, Meta is now embarking on a massive, open-ended spending cycle – one that feels less like investment and more like industrial-scale speculation.

Let’s look at the numbers. Meta expects to spend around $70 billion in capex in 2025. That’s not just high – it’s astronomical, even by Big Tech standards (and all of Big Tech is “going big” on AI CapEx to be fair). And the company has signaled that these levels are not a one-off but will continue “for the foreseeable future” as they double down on AI infrastructure: training, inference, data centers, and internal silicon.

Now, I’m not here to argue that AI is a bad bet. That would be intellectually lazy. There’s clearly a transformation underway – from foundational models to verticalized AI tools – and companies that get it right stand to unlock meaningful value. But here’s the thing: not every bet is equal. And not every environment is conducive to earning high returns on reinvested capital.

To frame this, I’ve found it useful to think about what makes a great reinvestment environment. In an earlier post, I described the ideal conditions like this:

Low or no competition

High predictability

A history of similar investments paying off

Simple, modular rollout strategies

Clear, unit-level economics

Optionality without excessive upfront capital

That’s the dream. That’s what you want when allocating large amounts of capital – clarity, control, and high odds of a positive payoff.

Now let’s hold that against what we’re seeing in AI:

Competition is fierce – every tech giant is spending aggressively (collectively, the spent HUNDREDS of BILLIONS of dollars)

The monetization model is still unclear in many cases (for Meta specifically, I think it is actually clearer than for others)

The pace of innovation makes ROI projections murky at best

Infrastructure is expensive, complex, and constantly evolving

And the unit economics of inference and training are volatile, and hard to predict

This isn’t like rolling out another software module or opening a new AWS region. It’s a high-cost, high-uncertainty environment – a so-called “wicked reinvestment environment.” And that’s what makes me uneasy.

Let’s do some math…

Suppose Meta targets a 10% return on this $70 billion investment. That means they need to generate an additional $7 billion in recurring annual earnings, starting effectively now. But that’s not how infrastructure investments work. The payoff is back-loaded. If the return doesn’t materialize until, say, 2026, the required earnings increase due to the time value of money. A two-year delay means they’d need around $7.7 billion annually to justify the same investment. If the returns only show up in 2030? You’re looking at $11.27 billion annually per year. The longer the delay, the steeper the hurdle.

And here’s the kicker: this isn’t a one-time spend. Meta’s capex has been on a steady incline – from around $15–20 billion just a few years ago to $40 billion last year and now $70 billion projected. If they continue at that clip – say, another $70 billion in 2026 – then to merely “stand still” in terms of return on capital, the company needs to produce incremental earnings growth on top of prior years’ targets.

That compounds quickly:

2025: $7B in new earnings

2026: another $7B – totaling $14B over two years

2027: up to $21B in total additional earnings needed

And so on...

And we haven’t considered Meta hiking the planned CapEx further.

This becomes a reinvestment treadmill. Unless the company can pull off extreme operating leverage or unlock truly new and massive revenue streams, the math starts to work against them. Worse, if the returns come in below that 10% bogey – or arrive too slowly – you’re suddenly talking about dilutive capital allocation (assuming 10% is your hurdle rate you could earn elsewhere). And if you're aiming for a 15% internal rate of return – something most ambitious long-term equity investors would reasonably ask for – the required earnings climb even more steeply. That $70 billion capex now needs to produce $10.5 billion in recurring income at a 15% hurdle. Delayed to year six? Nearly $17.6 billion annually.

The math is cold and unforgiving.

Now, you could argue Meta’s balance sheet can handle this. And that’s true. They’ve also got the cash flow. But that’s not the point. The issue is capital efficiency. Every dollar reinvested at a sub 10% that could have been returned to shareholders – it carries an opportunity cost that compounds over time.

And this gets to the heart of why I think Zuck, brilliant as he is, is showing signs of capital allocation drift. For most of the 2010s, Meta was almost perpetually undervalued relative to peers like Google. Investors flagged the reliance on advertising revenue (tail risk), the regulatory overhang, and what some saw as governance risk. Then, post-2022, that narrative flipped. Meta slashed costs, boosted margins, and the stock rerated. Suddenly, it was the “higher quality” business. But now? We’re back to depending on a single visionary who’s willing to go all-in on massive, uncertain bets. The metaverse didn’t pay off – at least not yet. And now AI is the new frontier.

Again, I’m not anti-AI. But I am pro-return-on-capital. And in this case, the numbers give me pause.

In my mind, this is no longer a “buy it and forget it” kind of stock. The capital allocation questions now sit at the center of the thesis. And when reinvestment starts defining a company’s future intrinsic value compounding rate, you want to be very sure the returns are real, not just hoped for.

Rebalancing Toward Asymmetry

Once I made peace with the decision to exit Meta, the next obvious question was: where should the proceeds go?

The best part is just ahead — unlock the full post to continue.

Investing is the one domain where better thinking compounds. If this intro gave you new insights, the full piece goes even deeper. A paid subscription is an investment in your decision-making process – and your returns.