Picture this: a small Canadian software company, quietly churning out niche tools for oil and gas engineers, suddenly finds itself at a crossroads!

On one side, the gritty, cyclical world of fossil fuels.

On the other, the shiny promise of the energy transition, with buzzwords like carbon capture and geothermal dangling like low-hanging fruit.

That’s where Computer Modelling Group Ltd. (CMG) lives right now, and I’ve spent way too many hours dissecting whether this stock—currently lounging around C$8/share—is a diamond in the rough or a risky bet dressed up as a sure thing run by a hired CEO who finds the right words in his letters but hasn’t delivered on the articualted promises yet.

I’m not here to sell you a fairy tale. CMG isn’t some flashy tech unicorn with a billion-dollar valuation running Super Bowl ads that everyone is talking about. No, it’s a boring business. A yet highly profitable one. And that’s what makes it interesting.

It’s a Calgary-based outfit with 320 employees and consultants (187 at CMG, 95 at subsidiary Blueware, and 38 at subsidiary Sharp Reflections), making software that helps petroleum engineers figure out how oil and gas flow underground.

Sounds thrilling, right? Okay, maybe not—unless you’re into reservoir physics or, like me, obsessed with finding undervalued companies with a story.

What hooked me was CMG’s pivot: it’s not just riding the oil train anymore. With 23% of its 2024 revenue tied to energy transition projects—like modeling CO2 storage—it’s trying to future-proof itself. Moreover, it’s attempting to becoome a serial acquirer (or at least sort of).

But can it pull it off? Or will it get stuck in the tar sands of a dying industry?

In this blog, I’ll take you through my journey of analyzing CMG—from its niche dominance to its attempt at a bold transformation under the CMG 4.0 strategy, launched in 2022 to reposition it as a serial acquirer in the making. Renowned investor Chris Mayer started buying shares sometime last year, too. So what is he seeing? I’ll unpack CMG’s competitive moat, financial strength, and growth prospects alongside risks that could make this investment NOT work out.

Part 1: Understanding CMG’s Business

Part 2: Moat, Quality, and Growth

Part 3: Good Management

Part 4: Debt and Financial Stability

Part 5: Fair Price

Part 6: Chris Mayer’s Thesis—A 100-Bagger Perspective

Part 7: Inversion and Risks

Part 8: Conclusion

Buckle up—it’s a deep dive worth your time.

Disclaimer: I do own CMG shares. The analysis presented in this blog may be flawed and/or critical information may have been overlooked. The content provided should be considered an educational resource and should not be construed as individualized investment advice, nor as a recommendation to buy or sell specific securities. I may own some of the securities discussed. The stocks, funds, and assets discussed are examples only and may not be appropriate for your individual circumstances. It is the responsibility of the reader to do their own due diligence before investing in any index fund, ETF, asset, or stock mentioned or before making any sell decisions. Also double-check if the comments made are accurate. You should always consult with a financial advisor before purchasing a specific stock and making decisions regarding your portfolio.

Part 1: Understanding Computer Modelling Group’s Business

When I began researching Computer Modelling Group Ltd. (CMG; not to be confused with Chipotle Mexican Grill ;-)), a Calgary-based software company, I was struck by its niche yet pivotal role in the oil and gas industry. CMG specializes in developing simulation software that enables petroleum engineers to model the flow of oil, gas, water, and other fluids through underground reservoirs—a critical capability for planning and optimizing production.

With a global customer base spanning approximately 60 countries, CMG generates revenue primarily through software licensing, supplemented by support and consulting services. As I delved deeper, I found a business model that’s both straightforward and sophisticated, though its reliance on the cyclical oil and gas sector introduces a layer of complexity worth exploring.

The Core of CMG’s Operations

CMG’s primary offering is a suite of reservoir simulation software that has become an industry standard for specific types of oil and gas reservoirs. Its flagship products—IMEX, GEM, and STARS—address distinct subsurface challenges.

IMEX is designed for conventional “black oil” reservoirs, simulating primary and secondary recovery methods.

GEM tackles more complex compositional and unconventional reservoirs, such as shale gas or CO2-enhanced recovery projects.

STARS, meanwhile, excels in thermal and advanced recovery processes, notably steam-assisted heavy oil extraction—a key application in regions like Canada’s oil sands.

Beyond these, CMG offers CMOST, an optimization tool that automates sensitivity analyses and history-matching for reservoir models, enhancing efficiency and accuracy.

In partnership with Shell, CMG has also developed CoFlow, an integrated software that connects reservoir simulations with wellbore and surface facility models, providing a holistic view of field performance.

The operational model is predominantly software-driven. CMG licenses its products either as perpetual licenses, accompanied by ongoing maintenance contracts, or as annuity/term licenses, which are renewed annually and represent the majority of revenue.

Hence, a significant portion of its software revenue is recurring, derived from these renewals and maintenance fees, offering a degree of financial stability.

Clients receive regular updates, technical support, and training as part of the package.

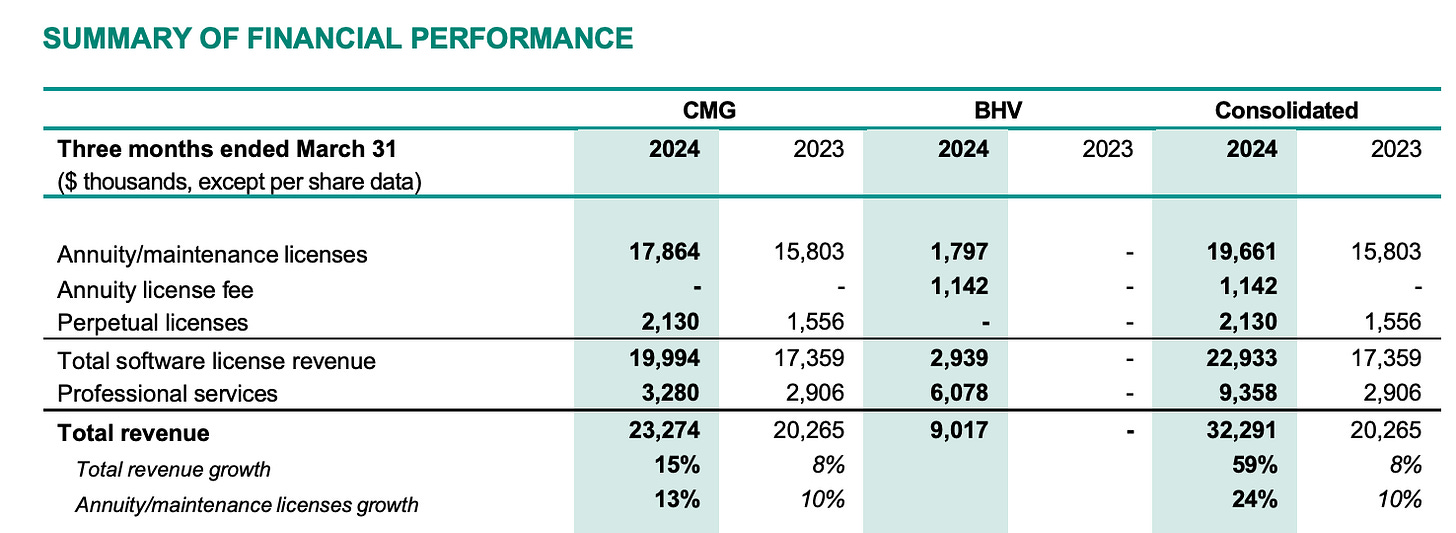

Additionally, CMG provides professional services—consulting and training—to assist with complex modeling or bespoke solutions. While this consulting segment is modest in size, it’s grown rapidly more recently, with fiscal 2024 revenue surging 141% year-over-year as CMG leverages its expertise to address talent shortages in subsurface engineering among clients.

But as CEO Pramod Jain stresses, the services business won’t be a primary focus going forward:

“Today, approximately 65% of our total revenue is recurring software revenue, compared to CMG’s 78% in the simulation business alone. Reorienting the revenue mix, especially from acquired companies, towards software is essential for driving profitability. Recurring software revenue is scalable in a way that services are not, offering higher incremental margins. This enhances profitability which in turn can boost free cash flow, enabling us to further our acquisition strategy. Our shift towards a higher percentage of recurring software revenue will primarily result from our focus on stronger software sales. A lesser impact will come from declines in professional services revenue including the ramp-down of CoFlow funding. We also expect a gradual reduction in tailored software development professional services within Seismic Solutions. This shift can contribute to strengthening our margin profile and cash-generating potential. As a result, total revenue growth will be less important than software revenue growth, margin expansion and free cash flow per share.“

The business requires no manufacturing or physical supply chain; its key resources are skilled software developers and reservoir engineers, making it a capital-light operation focused on intellectual capital.

The video below from an AWS event is four years old, but it still helped me get a better sense of what CMG actually does:

CMG’s Customer Base and Reputation

CMG serves a diverse, high-caliber clientele, including international oil companies, national oil companies, independent producers, consulting firms, and research institutions. As of a few years ago, the company boasted over 570 clients across 58 countries, a testament to its global reach and industry relevance. Its reputation is particularly strong in simulating heavy oil and advanced recovery methods—areas where it has established a dominant presence over decades.

For instance, in thermal heavy oil recovery, such as steam injection projects in Canada’s oil sands, CMG’s STARS simulator is widely regarded as a market leader with few viable alternatives. Similarly, its tools are highly respected for modeling unconventional shale reservoirs, including hydraulic fracturing and multi-phase flow dynamics.

“I have never encountered a brand as strong as CMG in my career. Our customers consistently emphasize that no other company matches CMG in terms of the scientific integrity of our products and the quality of our service. While other simulators are used, CMG is often regarded as the ‘North Star’ – the most trusted technology, backed by solid math and physics. This is a significant advantage.“ (CMG CEO Pramod Jain)

Customer perception underscores CMG’s value proposition. The company actively tracks satisfaction, reporting a Net Promoter Score of 68 in a recent survey—a very solid metric indicating strong loyalty and likelihood of recommendation.

This is bolstered by CMG’s flexible licensing structure, which allows large clients to deploy software across regions without additional per-seat costs, a feature that enhances cost-efficiency and ease of use.

Clients consistently praise the technical prowess of the software and the quality of support (see slide above), contributing to a retention rate that hovers above 98-99% for annual license revenue.

However, CMG’s deep ties to the oil and gas sector carry a dual edge: while its tools are indispensable for efficiency and safety—and increasingly for applications like carbon capture—some may view its fossil fuel focus unfavorably amid rising environmental scrutiny.

Industry Context: Simplicity Meets Cyclicality

CMG operates within a specialized corner of the software industry—upstream oil and gas simulation—that blends simplicity with inherent unpredictability. On one hand, the business is easy to understand: it develops mission-critical niche engineering software, akin to a software-as-a-service (SaaS) model, though historically rooted in perpetual licenses with a shift toward recurring subscriptions.

Unlike conglomerates with sprawling divisions, CMG focuses solely on subsurface modeling technology, generating revenue through license sales, renewals, and modest services. The recurring nature of its annuity and maintenance contracts—recognized ratably over time—provides a predictable revenue base, smoothing out some volatility.

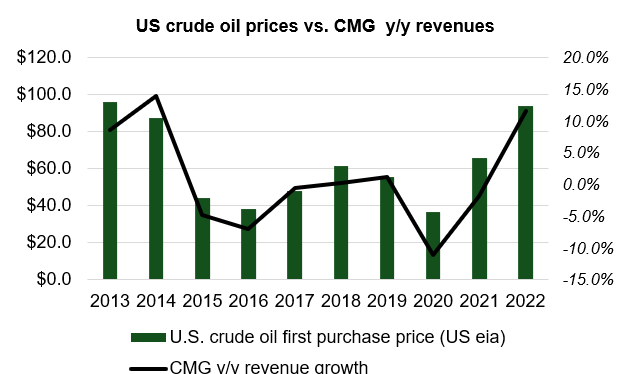

Yet, this predictability is tempered by the oil and gas industry’s cyclical nature. Demand for CMG’s software correlates with exploration and production activity, which ebbs and flows with oil prices and capital spending.

(paragraph from the 2024 annual report)

During boom periods, such as when oil prices are high, energy companies invest heavily in advanced simulation tools, driving new license sales and expansions. Conversely, downturns—like the 2014 oil price collapse or the 2020 pandemic-induced crash—prompt budget cuts, stalling growth or even triggering slight revenue dips as projects are deferred.

Historical data reflects this: post-2014, CMG’s revenue growth faltered as the industry retrenched. The upstream simulation market itself is niche—estimated at a few hundred million dollars globally, with one investor pegging the core reservoir simulation segment at $200 million in 2013, likely larger now with unconventional and transition-related growth.

Within this space, CMG’s fortunes are tied to capital expenditures on new oil and gas projects, a dynamic that distinguishes it from broader, more stable software sectors.

Despite this cyclicality, emerging trends offer a counterbalance. The increasing complexity of resource extraction—think shale or deepwater—and the push for efficiency and carbon management elevate the importance of simulation tools.

As noted further above, in its 2024 fiscal year, 23% of CMG’s core software revenue stemmed from energy transition projects, such as CO2 storage, geothermal, and hydrogen storage.

This diversification suggests that even as traditional oil production evolves, CMG’s technology retains relevance by adapting to new subsurface challenges; in fact I believe this may be a structural tailwind for the business.

As long as energy extraction or storage requires sophisticated modeling, CMG appears positioned to endure.

Why This Matters to Me

What drew me to CMG was this blend of focus and adaptability. It’s a small company—just over 300 employees—with a laser-sharp mission, yet it’s navigating a pivotal shift. Its entrenched role in oil and gas gives it a foundation, while its foray into energy transition applications hints at resilience. But the cyclicality can’t be ignored—it’s a double-edged sword that demands I assess both the stability of its recurring revenue and the volatility of its end market.

In the sections ahead, I’ll explore whether CMG’s competitive strengths and strategic moves outweigh these risks, starting with its moat and market position.

Part 2: Is CMG a Good Business? Assessing Moat, Quality, and Growth

After grasping what Computer Modelling Group (CMG) does and how it operates, let’s turn our attention to a critical question:

Is this a good business?

For me, that hinges on three pillars—general business quality attributes, existence of competitive barriers, and growth potential.

I argue that CMG isn’t just a niche software provider; it exhibits traits that suggest durability and superb profitability, even in a volatile industry.

In this section, I’ll dissect its competitive advantages, evaluate its financial strength, and explore its growth trajectory—past, present, and future. The findings paint a picture of a company with a strong foundation and promising avenues ahead, though not without challenges.

Competitive Moat: A Sticky Niche Leader

CMG’s competitive moat is one of the first things that impressed me. In the world of reservoir simulation software, it’s not a trivial tool you swap out on a whim—it’s deeply embedded in workflows. Once an oil company adopts CMG’s simulators—like IMEX, GEM, or STARS—for a project, switching to a competitor means retraining engineers, reworking years of calibrated models, and risking data comparability.

These high switching costs create a powerful lock-in effect, reflected in CMG’s near 98-99% annual license revenue retention rate. Clients rarely leave unless a project ends or a merger forces a change, giving CMG a sticky customer base that’s tough to unseat.

This advantage is amplified by CMG’s specialization. In thermal heavy oil recovery—think Canada’s oil sands—its STARS simulator is a standout, often described as a market leader with few peers.

A decade ago, it held a near-monopoly in unconventional reservoir modeling in Canada, a reputation that persists. For shale gas and complex recovery, CMG’s tools are similarly entrenched, built on decades of R&D in reservoir physics. This expertise isn’t easily replicated; new entrants face a steep climb to match CMG’s accuracy, reputation, and track record.

Globally, CMG is the #2 player in reservoir simulation, trailing only Schlumberger (SLB), whose Eclipse and Intersect simulators dominate conventional reservoirs with a historical 60% market share to CMG’s 25%.

But those numbers mask a key distinction: CMG excels in the growing niches of unconventional and advanced processes, while Schlumberger leads in legacy conventional fields.

Over time, CMG has chipped away at SLB’s customers—especially as shale and heavy oil rose in the 2010s—while losing fewer of its own, as a former CEO once noted. Other competitors, like Halliburton’s Nexus (now faded) or Rock Flow Dynamics’ tNavigator (a newer, cheaper option), pose limited threats. TNavigator has gained some traction, but CMG’s continuous upgrades—like GPU acceleration and cloud capabilities—keep it ahead. Recent acquisitions, such as Bluware-Headwave (BHV) and Sharp Reflections, expand its moat into seismic interpretation, positioning CMG as a broader subsurface software provider and enhancing customer stickiness.

This combination—switching costs, niche dominance, and a blue-chip client list across 60 countries—gives CMG pricing power and resilience. Its multi-decade lead in algorithms and ongoing R&D, often with partners like Shell, further fortify its edge. For a company of its size, this moat is a compelling reason I see it as a good business.

Business Quality: High Margins and Cash Flow

CMG’s financial profile reinforces its quality. As a software firm with proprietary products and low incremental costs, it boasts margins that many peers would envy. Historically, its core reservoir software business delivered gross margins around 80%, FCF margins of 30-35% and net profit margins of 20-30%, reflecting the high value clients place on tools that unlock millions in oil revenue.

ROIC has exceeded 30% in many years of the past, but has trended down in more recent years; still sitting at a strong 25.6% in 2024 though.

Several factors drive these fantastic numbers. First, recurring revenue—mostly from license renewals and maintenance—provides a stable base, covering fixed costs and reducing earnings volatility. Second, the cost of adding a new license is minimal; once developed, software scales cheaply, boosting margins. Third, CMG runs lean, with around 300 employees and no low-margin distractions like hardware. Even its consulting is high-value, not a profit drag. Finally, with no debt and C$63.1 million in cash at fiscal 2024’s end, CMG avoids interest costs and earns modest interest income, enhancing its financial flexibility.

Free cash flow (FCF) is another hallmark of quality. In its 2024 fiscal year, CMG generated C$0.44 per share in FCF, up 63% year-over-year, fueled by profit growth and tax benefits from an acquisition.

Historically, it converts earnings to cash efficiently, funding dividends (C$0.20/share annually) and retaining ample reserves.

Return on invested capital (ROIC) is also high, reflecting smart R&D and acquisition decisions—management even tied executive pay to ROIC in 2024 to prioritize quality growth (more on this further down below).

Recent margin dips (e.g., 34% EBITDA in Q2 FY25 due to BHV integration) are temporary.

All in all, the resilience shown underscores a top-tier business model.

Growth: Cyclical Past, Promising Future

CMG’s growth story is a tale of two eras. In the early 2010s, it rode the shale and heavy oil boom, hitting C$85 million in revenue by 2015. Then came the oil downturns—2014-2016 and 2020—when client budgets shrank, stalling growth and pressuring the stock. From 2015 to 2020, revenue flatlined or dipped, a reminder of its oil-linked fate. Yet profitability held, and R&D never wavered, setting the stage for a rebound.

When I first looked at the company (back then the stock was trading at a significantly higher price), my immediate reaction was “30x earnings for a company with a 10Y revenue CAGR of 3-4%? No, thanks!“

In 2023, the 10Y topline CAGR was <1%.

But there’s more to the story.

The business hit an inflection point in 2021-2022 under new CEO Pramod Jain and the “CMG 4.0” strategy. Since then, CMG has posted nine straight quarters of year-over-year revenue growth. Fiscal 2024 was a standout—revenue soared 47% to C$108.7 million, with 19% organic growth (the highest in over a decade) and 28% from acquisitions. Early fiscal 2025 (six months to Sep 30, 2024) showed core revenue up 6% and total revenue up 38%, signaling sustained momentum.

Looking ahead, I see multiple growth drivers. Organically, CMG can deepen penetration in markets like the Middle East and Asia-Pacific, upsell tools like CoFlow, and tap energy transition demand—as a reminder, 23% of 2024 revenue came from carbon capture, geothermal, and hydrogen projects, leveraging its CO2 modeling expertise.

Analysts project 11% FY 2026 earnings growth and 18-19% in EBIT growth, fueled by these trends and industry digitization.

Inorganically, acquisitions like Blueware (2023, seismic software) and Sharp Reflections (2024, 4D seismic analysis) expand its portfolio. Sharp, with €10 million in revenue, adds cloud-based tech that could scale via CMG’s network. Management’s M&A pipeline lets investors hope for more deals, potentially accelerating growth beyond its single-product past (the serial acquirers playbook of organic + inorganic growth).

Challenges remain—execution risks from acquisitions, capital allocation discpline (Jain and his team not paying up), and oil’s cycles could temper results.

But with a 5-10 year lens, I see mid-to-high single-digit organic growth, plus inorganic boosts, positioning CMG for a healthy trajectory if it navigates these hurdles well.

Total Addressable Market: Niche Constraints and Expansion Potential

As I assessed CMG’s growth potential, one question loomed large: What is the total addressable market (TAM) for its reservoir simulation software, and how does it shape the company’s runway for reinvestment?

Broadly speaking, I prefer global serial acquirers (“generalists”) over those focused on just one vertical (“specialists”). I prefer “programmatic” acquirers (small but frequent acquisitions) over “selective” or “large deal” acquirers.

That’s something I’ve learned from Serial Acquirers specialist REQ Capital (see slide below; with added annotations from me).

(Source: REQ Capital - “A Deep Dive into Shareholder Value Creation by Acquisition-Driven Compounders“)

CMG definitely falls in the “specialist” bucket and the two completed deals were decently large (pretty much one year’s worth of FCF), and there was one deal per year (low frequency). The company operates in a niche—the oil and gas simulation market—estimated at a few hundred million dollars globally; possibly $1 billion by 2030 (as estimated by CMG).

While it’s likely grown with unconventional plays and energy transition applications, it remains a relatively small pond. This narrow focus is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it underpins CMG’s moat—specialization breeds dominance, as seen in its leadership in thermal and unconventional modeling. On the other, it caps the pool of oil and gas companies CMG can realistically target, raising doubts about the scalability of its organic and inorganic growth ambitions; the compounding flywheel that serial acquirers often rely on to drive outsized returns.

For an investment thesis that is at least partly centered on organic reinvestment the TAM’s size is a critical variable. A limited market could constrain CMG’s ability to spin that flywheel continuously, especially if oil and gas capital spending plateaus or declines. Fewer new projects mean fewer new clients, and while CMG’s 570+ existing customers across 60 countries provide a solid base, saturating this niche could slow the pace of license sales growth over time. This is a notable negative compared to broader software firms with vast, diversified TAMs—think enterprise SaaS giants—where reinvestment opportunities abound.

But as will be discussed, the CMG thesis is also (or even primarily) about future inorganic growth opportunities (more on this in the next part of this analysis).

But even then, one could argue that the market for M&A activity in the oil & gas software space is limited. However, recent comments from CEO Pramod Jain at the 27th Annual Needham Growth Conference in January 2025 once again stressed his broader vision, suggesting that CMG’s M&A strategy could extend its TAM beyond oil and gas. He emphasized a “platform approach” to integrating acquisitions like BHV and Sharp Reflections, not just for synergies within upstream energy but as a blueprint for adjacent verticals. “If we do this right from overall building up the powerhouse for the upstream,” he said, “we can replicate that for any other verticals, whether that’s mining industry, groundwater industry. There are so many adjacent verticals that we can start to look at because diversification is important to us.”

He noted that CMG evaluates acquisitions on standalone merits—focusing on internal rates of return (IRRs)—but acknowledged that cost and growth synergies naturally enhance value, even if unmodeled.

A potential pivot to mining or groundwater—industries with subsurface modeling needs akin to oil and gas—could significantly expand CMG’s addressable market in terms of M&A activity. Mining, for instance, requires simulation for resource extraction and environmental management, areas where CMG’s physics-based expertise could translate. Jain admitted it’s “very early stages,” but the shift from one business to three (via BHV and Sharp) signals intent. If successful, this diversification could mitigate the niche TAM’s constraints, offering a longer runway for reinvestment and compounding—a tantalizing prospect for me as an investor.

Still, execution risk looms large; entering new verticals demands precision, and the learning curve could stumble.

For now, the TAM remains a question mark—one I’ll revisit as CMG’s M&A pipeline evolves.

Tying It Together

CMG checks the “good business” boxes for me. Its moat—rooted in switching costs and niche leadership—protects its market position. Its quality—high margins, strong cash flow, no debt—offers stability. And its growth, once stagnant, now has momentum from diverse sources. As I’ll explore next, management’s role and valuation will determine if this translates to a good investment, but the business itself stands out as a compelling case.

Part 3: Good Management—Steering CMG with Skill and Strategy

Having established CMG as a strong business with a competitive moat, high-quality financials, and promising growth, I next turned my focus to its management.

A company’s leadership can make or break its potential, and for CMG, I found a team that appears shareholder-friendly, strategically astute, and committed to long-term value. Under new CEO Pramod Jain since 2022, CMG has embraced a clear vision—dubbed "CMG 4.0"—while fostering a performance-driven culture and allocating capital prudently.

In this section, I’ll examine the leadership’s credentials, their alignment with shareholders, and their approach to capital deployment, all of which bolster my confidence in CMG’s trajectory.

Leadership Team: Experience Meets Ambition

CMG’s current CEO, Pramod Jain, took the reins in May 2022, marking a pivotal shift. With over 15 years in software leadership—including roles as President and COO of Plusgrade (a SaaS e-commerce firm) and a nine-year stint at Sabre Inc. (a global tech company)—Jain brings a proven track record in scaling tech businesses and executing acquisitions. His engineering Master’s degree and corporate finance diploma equip him with both technical and financial acumen, a blend I find well-suited to CMG’s ambitions. Since joining, Jain has pursued an analytical, decisive approach, emphasizing clear objectives over consensus-driven stagnation, as he outlined in his 2024 shareholder letter. Under his tenure, CMG has revitalized growth, completed two significant acquisitions, and accelerated innovation—early signs of effective leadership, though his era is still young at roughly three years.

Supporting Jain is a seasoned team. CFO Sandra Balic provides financial continuity, having served CMG for years, while technical leaders—such as the VP of CoFlow and Professional Services—bring deep reservoir engineering and software expertise.

The retention of key figures from acquisitions, like Sharp Reflections’ co-founder Bill Shea, ensures domain knowledge stays in-house. Historically, CMG’s leadership has been technically strong; founded by academics and later led by figures like Ken Dedeluk (over a decade as CEO), it built a robust foundation. Jain’s arrival adds a growth-oriented mindset to this legacy, a transition the Board endorsed as “the next chapter” for CMG, reflecting confidence in his global leadership skills.

“CMG’s values of entrepreneurial talent, extreme ownership, curiosity, customer centricity, collaboration, and integrity are our license to operate. Each team member lives these values daily, and they are integral in the relationships we build with customers, clients, and partners. When working with CMG, these values will ring true every time.“

What caught my attention, though, is the board’s composition—there’s substantial Constellation Software influence steering this ship. Mark Miller, Constellation’s COO and Volaris Group CEO, became Board Chair in 2022 after joining in 2019, bringing decades of experience in acquiring and growing vertical market software firms. John Billowits, a former Constellation CFO and Vela Operating Group CEO, joined in 2021, adding further software and M&A expertise.

This isn’t just recent board renewal with generic “software expertise”—it’s a deliberate injection of Constellation’s proven strategy, aligning with CMG 4.0’s acquisitive pivot. The 2022 transition from long-time Chair John Zaozirny to Miller was smooth, and with no governance scandals on record, this track record suggests a leadership team I can trust to navigate CMG thoughtfully toward a serial acquirer model.

Transparency and integrity also stand out. I found no notable controversies or governance issues in CMG’s history. Management communicates candidly via shareholder letters and earnings calls, acknowledging past growth stalls and outlining corrective actions. The 2022 CEO transition—from Ryan Schneider to Jain—was orderly, with Schneider stepping down amicably and the Board executing a clear succession plan. Recent Board renewal, now heavily influenced by Constellation’s expertise, further signals proactive governance. This track record suggests a leadership team I can trust to steer CMG thoughtfully.

(If you want to watch video footage of CMG’s CEO to “get a feel for” who you are dealing with, I recommend this recent panel discussion hosted by RedEye in March 2025)

Culture and Incentives: Aligning with Shareholders

Beyond credentials, I evaluated how management aligns its interests with shareholders and shapes CMG’s culture. Under Jain, the company has shifted toward a performance-driven ethos. In fiscal 2024, CMG overhauled executive compensation, tying bonuses and long-term awards to revenue, profit growth, and Return on Invested Capital (ROIC). Including ROIC—a metric of capital efficiency—ensures leaders prioritize profitable growth over reckless expansion and empire-building, a move I view as shareholder-aligned. It discourages overpaying for acquisitions or chasing vanity projects, directly linking pay to disciplined value creation.

CMG also introduced an innovative employee incentive in 2024: a portion of bonuses at all levels must be taken as company stock, purchased on the open market. This turns employees into shareholders, fostering an ownership mindset that I believe enhances accountability and long-term thinking.

Jain has emphasized building a culture around Objectives and Key Results (OKRs), with values like Extreme Ownership and Customer Centricity. This focus on results and ethical execution is crucial for a small firm aiming to scale while integrating acquisitions. Early indicators—such as sustained high customer retention and improved strategic clarity—suggest this cultural shift is gaining traction without sacrificing client relationships.

The integration of recent acquisitions (BHV and Sharp) tested management’s capabilities. While BHV initially represented a drag on margins, management addressed it transparently, reorganizing teams for scalability. By Q3 FY25, profitability rebounded, and analysts praised CMG’s integration efforts.

Closing the Sharp deal just a year after BHV could give investors confidence in their sourcing process, and retaining Sharp’s founder signals a savvy approach to preserving acquired talent.

Then, there’s the question of price discipline: Can the CMG leadersheet team patiently wait for opportunities that will generate attractive returns for shareholders?

Kip Johann-Berkel expressed some doubts in the tweet below. CMG’s management team argues that both acquisitions were on the “growthier” side combined with synergies with the platform CMG is building (expanding the product line), justifying higher multiples. I’m not entirely sure who’s right here, but this should be carefully tracked by investors as CMG is basically a stage 0 serial acquirer (read: NOT a serial acquirer (yet)) without a proven track record.

Kip also highlighted in the tweet below how Blueware’s growth has significantly slowed since the acquisition deal (again, something that should give investors pause):

CEO Letters: A Shareholder’s Dream

As I pored over CMG’s recent shareholder letters from CEO Pramod Jain, I found myself nodding in approval—his words are music to an investor’s ears. Jain checks every box I look for in a leader: a laser focus on free cash flow per share, an emphasis on returns from reinvestment, a long-term perspective, a willingness to own mistakes, and a commitment to disciplined capital allocation.

Hopefully, these aren’t just platitudes; his letters articulate a vision that aligns management with shareholders like me, and the specifics he shares deepen my confidence in CMG’s prospects.

Take his stance on performance: “While I am deeply tuned into our quarterly performance, I believe our annual performance is a better reflection of our progress and potential over the long term.” This long-term focus is paired with a clear priority—“total revenue growth will be less important than software revenue growth, margin expansion and free cash flow per share.”

For Jain, it’s about quality, not vanity metrics. He doubles down on reinvestment, noting, “The combination of both profitable growth and free cash flow generation to redeploy into our acquisition strategy will be our path to long-term value creation,” and calls acquisitions “where compounding will have the greatest impact on CMG.”

This echoes my own lens—FCF/share growth and high-return reinvestment are the engines of compounding wealth.

Jain’s transparency and accountability shine through too. Reflecting on a Q3 FY25 revenue dip, he wrote, “The decline in A/M revenue was largely due to a contract that didn’t renew… While it is not unusual to have small fluctuation in renewals, I committed to being fully transparent with our shareholders and to presenting a balanced view of wins and losses.”

This “extreme ownership”—a cultural pillar he’s championed—resonates with me; admitting setbacks builds trust. He’s also proactive about incentives, updating “CEO and CFO performance metrics… to include not only revenue growth and adjusted operating profit but also Return On Invested Capital (ROIC),” and mandating that “bonuses will be awarded as a combination of cash and a contribution to a share purchase plan,” buying CMG shares on the market. These moves tie pay to shareholder value and foster an ownership mindset across the team.

On acquisitions, Jain’s discipline stands out: “I am often asked about the expected pace of our acquisition strategy… My response is always that ‘it depends’. It is important to stress that patience and a long-term view will matter.” This isn’t a rush to empire-build; it’s a measured approach to ensure deals that compound value over time. He acknowledges the effort required—“We will have to work hard and with diligence to maintain our competitive edge”—and credits “establishing a performance-based culture and compensation” as a success. For me, these letters aren’t just updates; they’re a blueprint of a management philosophy I can get behind, reinforcing CMG’s potential as a well-run business.

Capital Allocation: Balancing Growth and Returns

Capital allocation is where management’s priorities become tangible, and CMG’s approach strikes me as balanced and prudent. Historically, the company has been generous with shareholders, paying a steady quarterly dividend (which btw I’d like to see cut)—currently C$0.05 per share (C$0.20 annually), yielding about 2.5% at today’s price.

Even during the 2020 downturn and recent acquisition spending, CMG maintained this payout, signaling confidence in its cash generation. Management’s stated goal—“preserve long-term per-share profitability while driving growth”—guides this strategy, avoiding reckless dilution or cash hoarding.

Reinvestment is disciplined yet forward-looking. CMG has consistently funded R&D, even in lean years, to keep its software competitive—a necessity given its reliance on innovation. Recent efforts, like developing carbon capture simulation tech and CoFlow with partners like Wood PLC, aim to secure future growth in emerging markets. This measured approach ensures the core business evolves without overextending resources.

The big shift came with acquisitions. Recognizing excess cash accumulation, management pivoted to “prudently invest” in durable revenue streams. The 2023 purchase of Bluware-Headwave (BHV) for ~C$30 million and the 2024 acquisition of Sharp Reflections for €25 million—both funded with cash, no debt—expand CMG into seismic software and cloud-based analysis. Sharp, with €10 million in revenue and low double-digit margins, was acquired at a 2.5x sales multiple, while BHV added C$20.8 million in revenue in its first six months. These deals align with CMG’s domain, targeting cross-sell synergies and a larger addressable market. Post-Sharp, CMG retained ~C$20-25 million in cash, preserving flexibility for further moves. This “tuck-in” strategy—buying niche leaders to scale globally—feels strategic, not empire-building, and leverages CMG’s cash-generative model effectively.

Equity discipline is notable too. CMG avoids significant share issuance, relying on cash for deals, and the employee stock program buys shares on the market, supporting the price without dilution. Share count hovers around 82 million, with only modest creep. While buybacks haven’t been a focus—likely due to limited liquidity and growth priorities—excess cash is deployed where returns are highest: R&D and acquisitions.

Why Management Matters to Me

CMG’s management strengthens my investment case. Jain’s experience and vision, paired with a capable team, provide strategic direction. Incentives tied to ROIC and stock ownership align interests with mine as a shareholder. Capital allocation—balancing dividends, R&D, and smart acquisitions—demonstrates prudence and ambition.

Part 4: Debt and Financial Stability—A Rock-Solid Balance Sheet

As I evaluated Computer Modelling Group (CMG), I of course had to asses the company’s financial health as well. In an era where many companies lean on debt to fuel growth, CMG takes a different path: it operates with very little debt and maintains substantial cash reserves. This conservative approach reduces risk and enhances flexibility, a trait I find particularly reassuring given the cyclical nature of its oil and gas end market.

In this section, I’ll explore CMG’s debt position—or lack thereof—and assess how its balance sheet strength supports its long-term prospects.

No Debt, Ample Cash

CMG’s balance sheet is a model of prudence. As of the latest reports, the company carries zero bank debt and little bond obligations—a fact management has consistently highlighted.

“At December 31, 2024, CMG Group had $39.7 million in cash, no borrowings, and access to a $2.0 million line of credit with its principal banker, of which $0.6 million is available for use. The Company’s primary non-operating use of cash was for acquisitions, dividend payments and repayment of lease liabilities. Management believes that the Company has sufficient capital resources to meet its operating and capital expenditure needs.“

This isn’t a recent development; CMG has avoided debt for years, funding operations and growth entirely from cash flow. Even minor liabilities, such as lease obligations (e.g., ~C$2.3 million), are negligible. In essence, CMG is debt-free, a rarity that eliminates typical financing risks like interest rate exposure or covenant breaches.

Complementing this is a robust cash position. At the end of fiscal 2024, CMG held roughly C$40 million in cash, even after acquiring Sharp Reflections. By late 2024, prior to the Sharp Reflections purchase, cash stood at ~C$64 million. The €25 million Sharp deal (roughly C$37 million) likely reduced this to ~C$20-25 million, depending on interim cash generation. This cash cushion—relative to annual expenses—provides a buffer against downturns and firepower for strategic acquisition moves. With no heavy capital expenditure needs (as a software firm, capex is limited), most of this cash is truly discretionary, amplifying CMG’s financial agility.

Financial Flexibility and Risk Mitigation

The absence of debt translates to significant advantages. Without interest payments or refinancing deadlines, CMG faces no pressure to service obligations during an oil industry slump—a scenario I’ve seen derail leveraged peers in past cycles. If oil prices crash and client budgets tighten, CMG can lean on its cash reserves to sustain dividends (again, I’d rather see the dividend being cut to have more firepower for acquisitions) and R&D without external financing.

(Oil prices really took a beating yesterday; March 4)

This resilience lowers its risk profile; equity investors like me aren’t subordinated to creditors, enhancing safety in a worst-case scenario.

This flexibility also enables opportunity. The BHV and Sharp acquisitions—both cash-funded—demonstrate CMG’s ability to act swiftly without bank approvals or equity raises.

Post-Sharp, the remaining cash, plus ongoing free cash flow, positions CMG to pursue further deals or weather unexpected challenges. Management’s policy of parking excess cash in interest-bearing accounts ensures it earns a modest return until deployed, a small but smart detail in today’s higher-rate environment.

A Conservative Choice with Upside

Could CMG benefit from some leverage to lower its cost of capital? Perhaps, but I see the debt-free stance as a strength. Given its small size (~C$650 million market cap) and exposure to oil’s volatility, avoiding debt minimizes downside risk—a prudent choice over chasing marginal gains via leverage.

The company’s high returns on capital (ROIC) suggest it doesn’t need debt to fund growth. Currency fluctuations (revenues in USD, costs in CAD) pose a minor reporting risk, but with no foreign debt and a global footprint, CMG is naturally hedged to some extent.

For me, this financial stability is a cornerstone of CMG’s appeal. It’s not flashy, but it’s a fortress balance sheet that reduces worry, letting me focus on earnings and growth potential. With no debt dragging it down, CMG’s foundation looks solid—next, I’ll assess if its stock price reflects this strength.

Part 5: Fair Price—Is CMG Stock a Bargain or a Trap?

With CMG’s business strengths, management quality, and financial stability in focus, I now turn to the ultimate question: Is the stock priced fairly?

Valuation ties every piece of my analysis together—moat, profitability, growth, and resilience—and determines if CMG is worth my investment dollars.

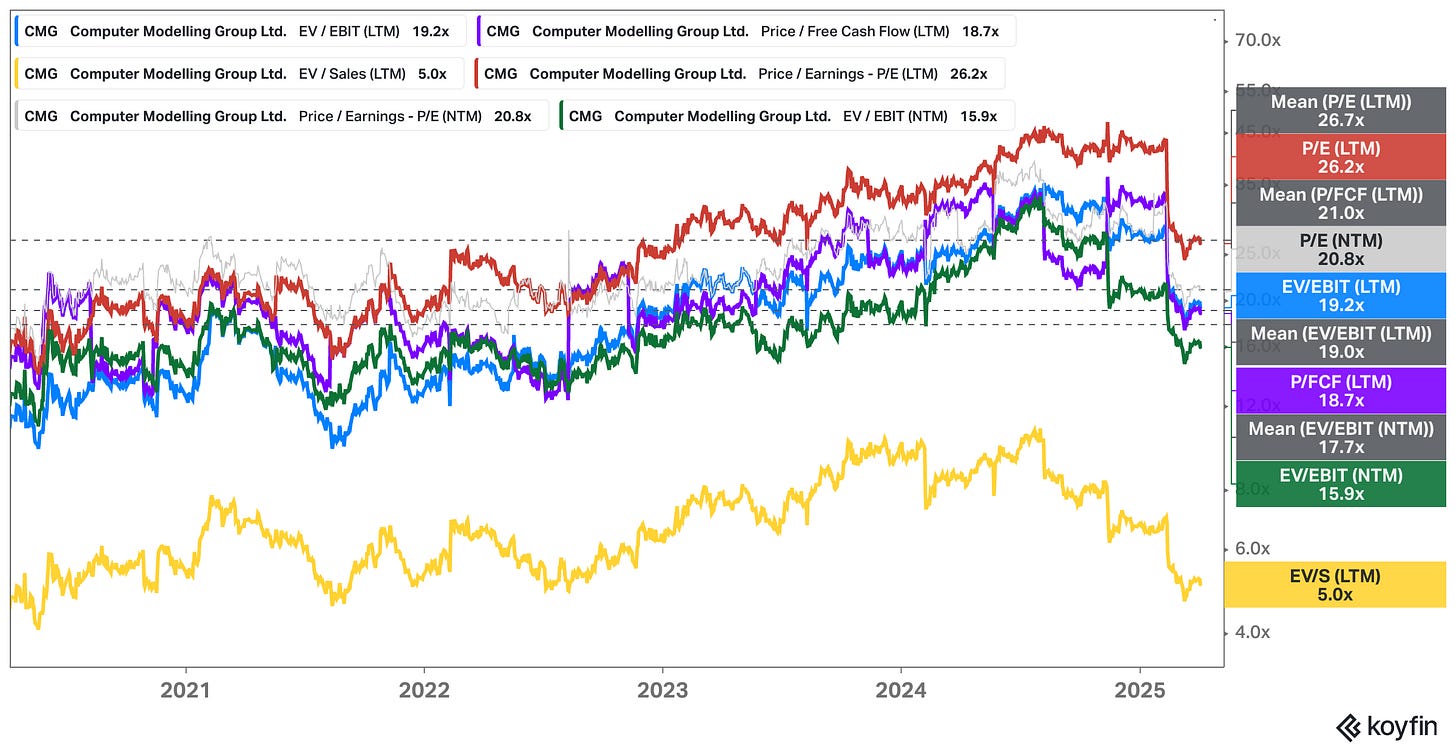

As today, the stock trades around C$8 per share, down from a 52-week high of around C$14, reflecting a significant pullback.

At this level, it carries a trailing P/E of ~26x, a forward P/E of ~21x, and a 2.5% dividend yield. On the surface, these multiples aren’t screaming “cheap,” but for a high-margin software company with a new capital allocation policy and hopefully renewed growth, they may undervalue its potential.

In this section, I’ll assess CMG’s current valuation, weigh the upside against the downside, and determine if the risk-reward balance justifies a closer look.

Total Return Analysis

Over the last twelve months, CMG posted a solid 27% FCF margin. CMG’s 10-year median FCF margin, however, stands at 33%. S0 I’m already willing to underwrite that CMG in its current form can continue to produce FCF margins of 30%, which gives us ~C$38.4 million in FCF based on the LTM revenue of ~C$128 million. Based on an EV of ~C$646 million, that gives us a starting multiple of 16.8x FCF.

I’m now assuming 10% FCF growth in my base case, a 20x exit multiple in 2035, and no share count reduction. With these inputs, you arrive at a ~12% price CAGR. Add the 2.5% dividend yield, and you get a nice 14%-ish return with possibly room to the upside if management proves itself as an intelligent capital allocator.

Hopefully, my projected 10% FCF growth CAGR is too conservative as the serial acquirer model—some organic growth + high single-digit/low double-digit inorganic growth (by buying companies at a great price)—could/should lead to faster compounding, and upside optionality if integration continues to be disciplined and value-accretive.

This scenario assumes oil software demand persists and new markets like carbon capture and storage (CCS) take off. With 23% of revenue already from transition projects and global CCS incentives rising, CMG’s expertise in CO2 modeling positions it for secular growth. A cyclical oil upswing could amplify this, as seen in 2022-2023 when license sales surged. For me, the upside lies in CMG proving its transformation—shifting from an oil proxy to a diversified subsurface software & platform leader.

Downside Risks: What Could Go Wrong?

At C$8, near its 52-week low, CMG already reflects some pessimism, limiting downside in my view. Its debt-free balance sheet and recurring revenue (~98% retention) provide a safety net; even in a severe oil downturn, CMG would likely remain profitable and lean on its C$20-25 million cash pile. The 2.5% dividend—historically maintained through tough times—offers a floor, paying me to wait. In a dire scenario (e.g., oil demand collapsing faster than expected), growth could stall, and the dividend might face pressure.

Still, risks linger. Liquidity is low (daily volume ~C$3 million), amplifying volatility—news or oil price swings could spark 5-10% moves. Some investors may apply an “energy discount” due to ESG concerns, capping the multiple despite green revenue. If integration costs persist or acquisitions falter, earnings could disappoint, keeping the stock range-bound.

Peer Context and Strategic Value

Direct public comps are scarce—Schlumberger’s software is part of a broader empire—but engineering software peers like Ansys or Autodesk trade at 30-40x earnings, reflecting recurring revenue and scale. Niche software firms often fetch premiums in acquisitions; Constellation Software buys similar businesses at 2-5x sales (traditionally CSU targets acquisitions at lower multiples—often below 2x revenue—but there have been instances where it has paid higher multiples, particularly for larger or strategically significant acquisitions).

One could conclude that hence CMG’s 5x sales multiple suggests it’s at least not overpriced. It could even be an acquisition target itself, though management seems intent on buying, not selling.

My Final Take on Fair Price

CMG isn’t a dirt-cheap value play, but I see it as a quality business at a sensible price. As I don’t think it’s a no-brainer here, I made it a fairly small bet for now (roughly 5% of the portfolio). But the risk-reward feels favorable: limited permanent loss (cash and recurring revenue as a backstop) and significant upside if CMG executes its CMG 4.0 strategy.

Part 6: Chris Mayer’s Thesis—A 100-Bagger Perspective

Chris Mayer, author of 100 Baggers, bought the stock in late 2024, likely at C$11-12, as shared in a Quartr interview.

His thesis caught my eye, blending themes I’ve explored—management, growth, and valuation—into a long-term investor’s lens. Mayer sees CMG as “a sleep-well-at-night investment” with “a steady, high-return, cash-spinning, moaty software business” and “lots of room to deploy capital in a big market.”

He’s drawn to the Constellation Software influence—Chairman Mark Miller, a Constellation board member as largest shareholder, and an ex-CSI acquisitions head—plus CEO Pramod Jain’s adoption of CSI-style compensation in 2024, rewarding ROIC and growth with mandatory share purchases. “The CEO gets it,” Mayer said, praising the incentives and team.

Mayer views the November 2024 sell-off—triggered by a soft quarter—as “a gift for longer-term shareholders,” dropping CMG to around C$10 and yielding “a very good valuation.”

He highlights its balance sheet strength and M&A potential, noting only two deals so far (BHV, Sharp) but expecting more as CMG ramps up.

One critique: the dividend, which he’d “expect them to cut or do away with entirely” to fund acquisitions.

For Mayer, CMG has “the whole package”—great incentives, team, returns, and growth runway—making it a stock he plans to hold “for a long time.” His perspective, rooted in finding multi-baggers, reinforces my interest: if a seasoned investor like Mayer sees CMG as a compounding machine in the making, it’s a signal this niche player could have outsized potential—provided execution holds.

Part 7: Inversion and Risks—What Could Go Wrong with CMG?

After highlighting CMG’s strengths—its moat, quality, growth, management, and valuation—I now shift to a critical exercise: inversion. What could derail this investment? A prudent analysis demands I consider the downside, imagining scenarios where CMG falters or the thesis fails.

Thus, in this section, I’ll outline the key risks, assess their likelihood and impact, and reflect on how they shape my view of CMG’s risk-reward profile.

Oil & Gas Cyclicality: The Boom-Bust Threat

CMG’s fortunes are tethered to the oil and gas industry, a sector notorious for its cycles. A sharp drop in oil prices—say, from geopolitical shocks or a recession (hard to believe the US is not about to enter one at the moment)—could slash client budgets, slowing license sales or prompting cancellations. I’ve seen this before: during the 2014-2016 oil crash and 2020’s pandemic slump, CMG’s growth stalled as projects were deferred.

(US recession risk according to prediction markets)

In an extreme scenario, a prolonged low-price environment could dry up exploration and enhanced recovery work, shrinking demand for simulation tools. Some clients—smaller independents—might even fail, risking non-renewals.

While CMG’s low churn rates offer a buffer (critical software isn’t easily dropped), a multi-year downturn could erode growth and undermine pricing power. This cyclicality, driven by unpredictable factors like OPEC moves or global demand shifts, is a risk I can’t control but must monitor.

Energy Transition: Opportunity or Obsolescence?

The energy transition is a double-edged sword. I’ve touted CMG’s 23% revenue from carbon capture and storage (CCS) and geothermal as a growth driver, but what if it falters? If CCS adoption lags—due to policy failures or cheaper alternatives—and oil demand peaks faster than expected (e.g., from renewables and EVs), CMG’s addressable market could shrink.

In a bearish 10+ year scenario, fossil fuel investment dwindles, and new transition markets fail to scale, leaving CMG stranded. Could it pivot to geothermal or hydrogen? Possibly, but these niches might not match oil’s profitability. While net-zero forecasts still require significant oil and CCS activity through 2030—supporting CMG’s relevance—overestimating transition revenue or underestimating oil’s decline could expose me to long-term obsolescence risk.

(PS: The fact that Buffett himself keeps increasing his oil exposure quarter after quarter is one piece of the puzzle that lets me sleep well at night)

Competition and Disruption: A Moat Under Siege?

CMG’s moat feels robust, but competition looms. Schlumberger (SLB), the #1 player, could counter CMG’s gains with aggressive pricing or enhanced simulators, leveraging its vast resources. If SLB bundled software into larger service contracts at a discount, budget-conscious clients might consolidate, eroding CMG’s share. Smaller rivals like Rock Flow Dynamics’ tNavigator—modern and cheaper—could also chip away, especially among mid-tier firms or regions like Asia. Technological disruption adds another layer, and here I pause to consider a broader trend affecting all SaaS companies: artificial intelligence (AI).

Could AI upend CMG’s business? In theory, AI represents a material risk to SaaS firms like CMG by driving down the cost of coding—potentially to near zero over time—as generative tools automate software development. This could commoditize parts of the industry, much like offshoring work to India slashed labor costs in the past. For CMG, where proprietary reservoir simulation software is the core offering, an AI-driven competitor might one day replicate its physics-based models faster and cheaper. Imagine an AI that learns from vast field data to optimize reservoirs without traditional simulation—a leap that could reduce reliance on CMG’s tools.

While this scenario feels distant—reservoir physics is intricate, and data-driven models are more likely to augment than replace simulation—it’s a risk I can’t dismiss outright. Open-source AI tools for CCS or geothermal, backed by academia, could further pressure commercial sales if they gain traction.

Yet, my view is more tempered. AI may lower development costs, benefiting CMG as much as its rivals by reducing R&D expenses. The real challenge isn’t writing software—it’s selling, installing, and supporting it. Distribution remains king, and CMG’s entrenched client relationships (570+ across 60 countries) and high retention give it an edge. Stickiness and integration are equally vital; engineers rely on CMG’s tools being deeply embedded in workflows, with years of calibrated data and training. Switching costs—retraining staff, rebuilding models—protect CMG even if AI churns out alternatives. Support, too, is a differentiator; CMG’s consulting and training services add value AI can’t easily replicate yet.

So, while AI could disrupt over a decade-plus horizon, CMG’s moat—built on distribution, integration, and service—offers a buffer.

Still, I’ll watch for AI-driven entrants or SLB leveraging AI to leapfrog, as CMG must keep innovating (cloud, GPU, AI integration itself) to stay ahead.

In sum, competitive risks—whether from SLB’s scale, tNavigator’s pricing, or AI’s potential—test CMG’s defenses. Its moat buys time, but a misstep in R&D or an unforeseen tech leap could erode its advantage.

Acquisition Execution: Growth’s Achilles’ Heel

CMG’s M&A strategy—BHV in 2023, Sharp in 2024—drives growth but introduces execution risk. CMG's management noted that while the Blueware acquisition led to increased revenue, it also resulted in a short-term reduction in consolidated profitability margins. Cultural clashes or key talent departures from acquired firms (e.g., BHV’s developers or Sharp’s founder) might stall progress—small software outfits often hinge on a few stars. Cross-selling synergies may not materialize if clients resist new offerings, and overextension could distract from core development, letting competitors close the gap. A larger future deal might tempt debt or equity issuance, adding financial risk. So far, CMG’s cash-funded, strategic approach mitigates this, but as acquisitions pile up, execution becomes a bigger variable I must watch.

Talent Retention: The Human Factor

CMG’s success rests on its people—engineers and developers crafting its sophisticated tools. Losing key talent—to tech giants, competitors, or startups—could slow innovation or weaken support. The acquisition spree heightens this risk; if BHV or Sharp staff exit, specialized knowledge walks out the door. While equity-based bonuses (introduced in 2024) should aid retention, cultural missteps during rapid change could disrupt morale. An extreme scenario—an exodus of a core team—might even spark a rival, though this seems unlikely en masse.

Client Concentration and External Shocks

Though CMG serves 570+ clients, a few majors likely drive outsized revenue. Losing a top client—say, a supermajor switching to SLB—or industry consolidation forcing software “rationalization” could dent growth.

Exact concentration isn’t disclosed, but we do know that according to the Q3 report, “During the nine months ended December 31, 2024, one customer comprised 25% of the Company’s total revenue (nine months ended December 31, 2023 – one customer, 18.3%).“

As Rusholme Capital learned from CMG’s IR team, that customer is Shell (see tweet below.

Moritz highlighted in the tweet above how the top-1 customer concentration level developed over time.

Beyond this, external risks like sanctions (restricting sales to certain countries), currency volatility (USD revenue, CAD costs), regulatory shifts, or cybersecurity breaches (damaging trust) could disrupt operations.

These are manageable but add noise to the outlook.

The Worst-Case Scenario

Inverting fully, what would make CMG a bust? Picture a perfect storm: a sustained oil price crash guts demand, SLB strikes back, key staff leave, and acquisitions flop—new products don’t sell, dragging profitability. Revenue declines, the dividend gets cut, and the stock languishes below C$8. Even here, CMG’s debt-free status prevents collapse—it’d survive, just diminished.

This extreme feels remote; recurring revenue, cash reserves, and transition exposure cushion the blow. But it’s a reminder not to assume flawless execution.

Part 8: Conclusion: CMG—A Mission-Critical Gem Worth the Risk?

After dissecting Computer Modelling Group from different angles—its niche moat, cash-rich stability, and ambitious CMG 4.0 pivot—I believe the risk-reward setup is attractive.

At C$8, it’s a high-quality business trading at a price that offers upside if management can deliver on its promises. This thesis is backed by Constellation-savvy directors and a CEO whose shareholder-friendly vision sings my tune. The growth runway—spanning oil, carbon capture, and maybe even mining—hints at a serial acquirer in the making, yet the oil industry’s volatility and acquisition risks keep me grounded.

For me, CMG balances reward (doubling potential over five years) with resilience (no debt, sticky revenue), but it’s not a slam dunk yet—execution and patience are key.

If you’re hunting for a small-cap software play with big ideas, CMG’s worth a hard look—just don’t skip your own due diligence.

Disclaimer: I do own CMG shares. The analysis presented in this blog may be flawed and/or critical information may have been overlooked. The content provided should be considered an educational resource and should not be construed as individualized investment advice, nor as a recommendation to buy or sell specific securities. I may own some of the securities discussed. The stocks, funds, and assets discussed are examples only and may not be appropriate for your individual circumstances. It is the responsibility of the reader to do their own due diligence before investing in any index fund, ETF, asset, or stock mentioned or before making any sell decisions. Also double-check if the comments made are accurate. You should always consult with a financial advisor before purchasing a specific stock and making decisions regarding your portfolio.

Great write-up! Thank you!