What Prediction Markets Reveal About Stock Picking

A Harsh Mirror for Investors? What Happens When Markets Discover the Truth First

Prediction markets are having a moment, and not a quiet one.

The sudden rise of Kalshi, capped by its $11 billion valuation and the instant celebrity of Luana Lopes Lara – now the youngest self-made female billionaire –, has dragged the entire category from the fringes of finance into the mainstream.

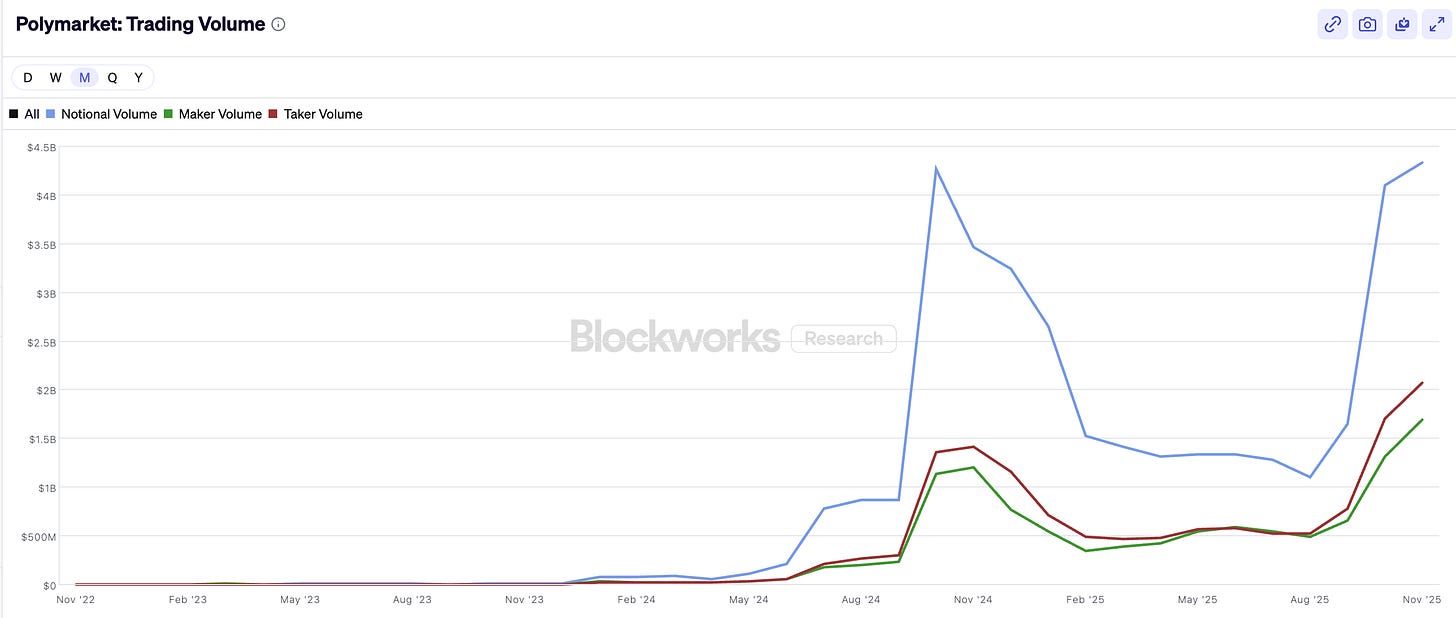

Polymarket is growing at breakneck speed. Even Robinhood is experimenting with event contracts that sit somewhere between betting slips and micro-futures.

Whether these instruments belong in the realm of investing, speculation, or pure entertainment is already a contentious question. I’m not entirely sure myself. What I am sure about is that their popularity is revealing something far more interesting than the surface narrative of gamified prediction.

Prediction markets offer an easy-to-grasp way to observe how auction-driven systems absorb information. They compress the mechanics of price discovery into a narrow, almost clinical format.

A simple contract that resolves into yes or no by a fixed date forces participants to translate every incoming piece of news into updated probabilities. That constant weighing of information against price is a process you rarely see so clearly in other markets.

What’s fascinating is how often these markets settle near the correct outcome long before expert commentary or media consensus catches up. I’ve seen it repeatedly.

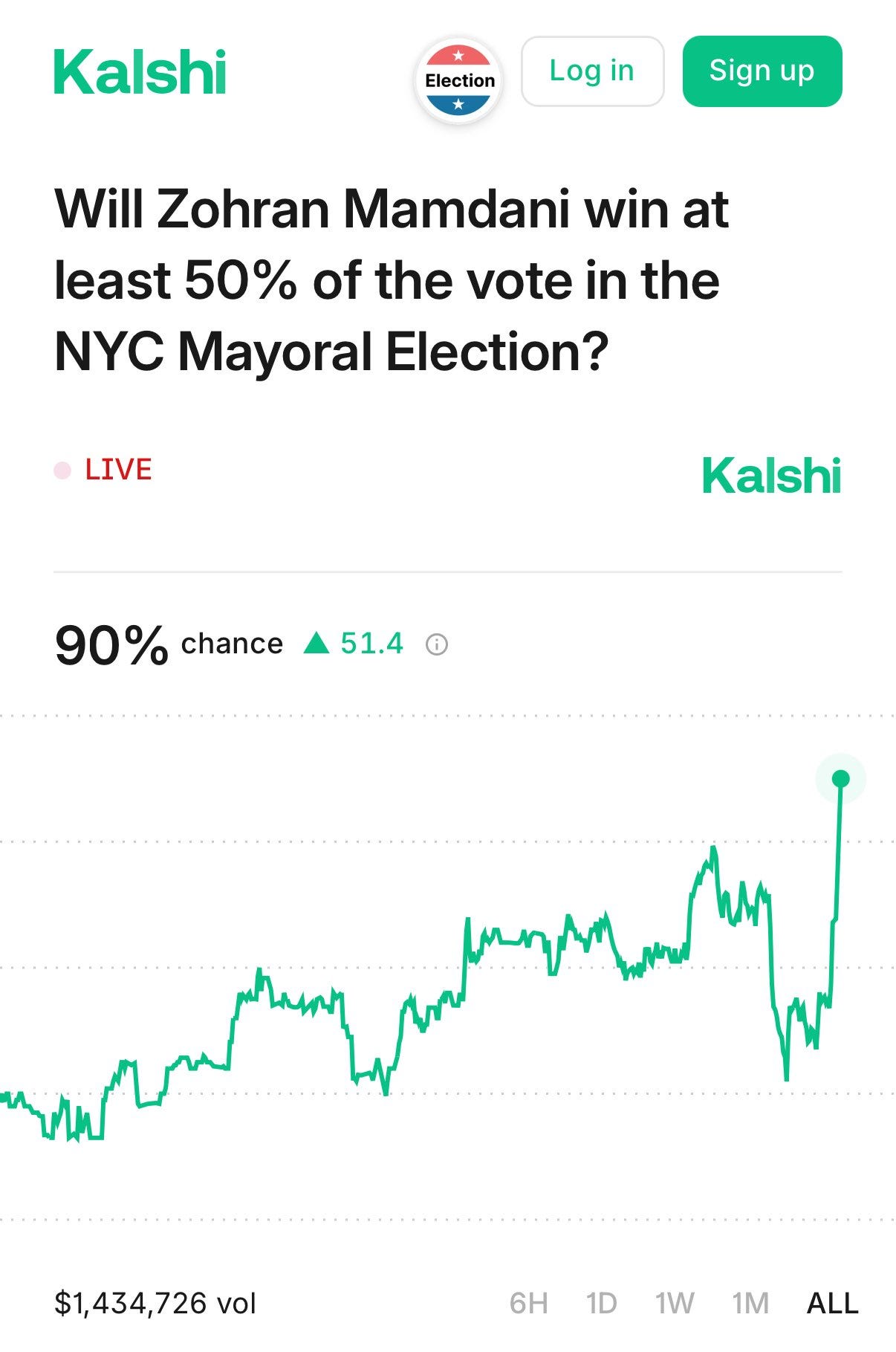

Election probabilities tightening weeks before pollsters adjusted their models.

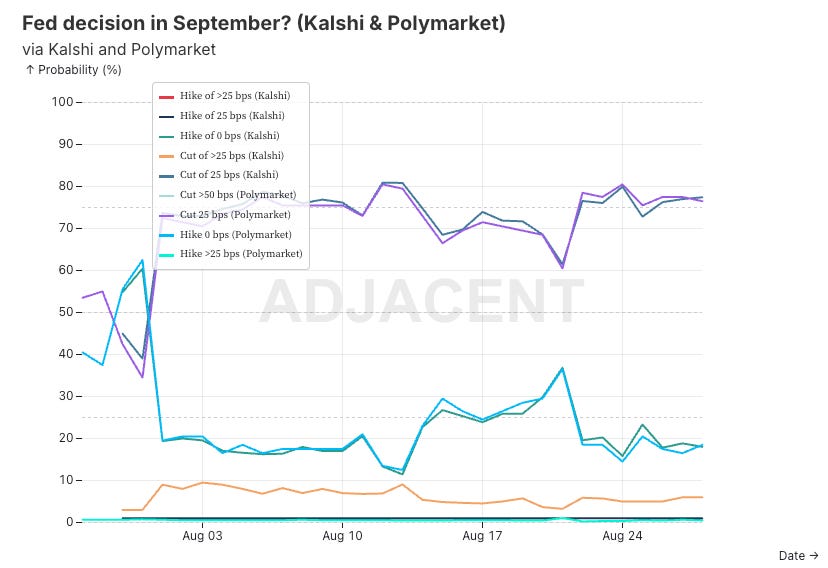

Contract prices for central bank decisions shifting hours after a subtle comment from a single policymaker.

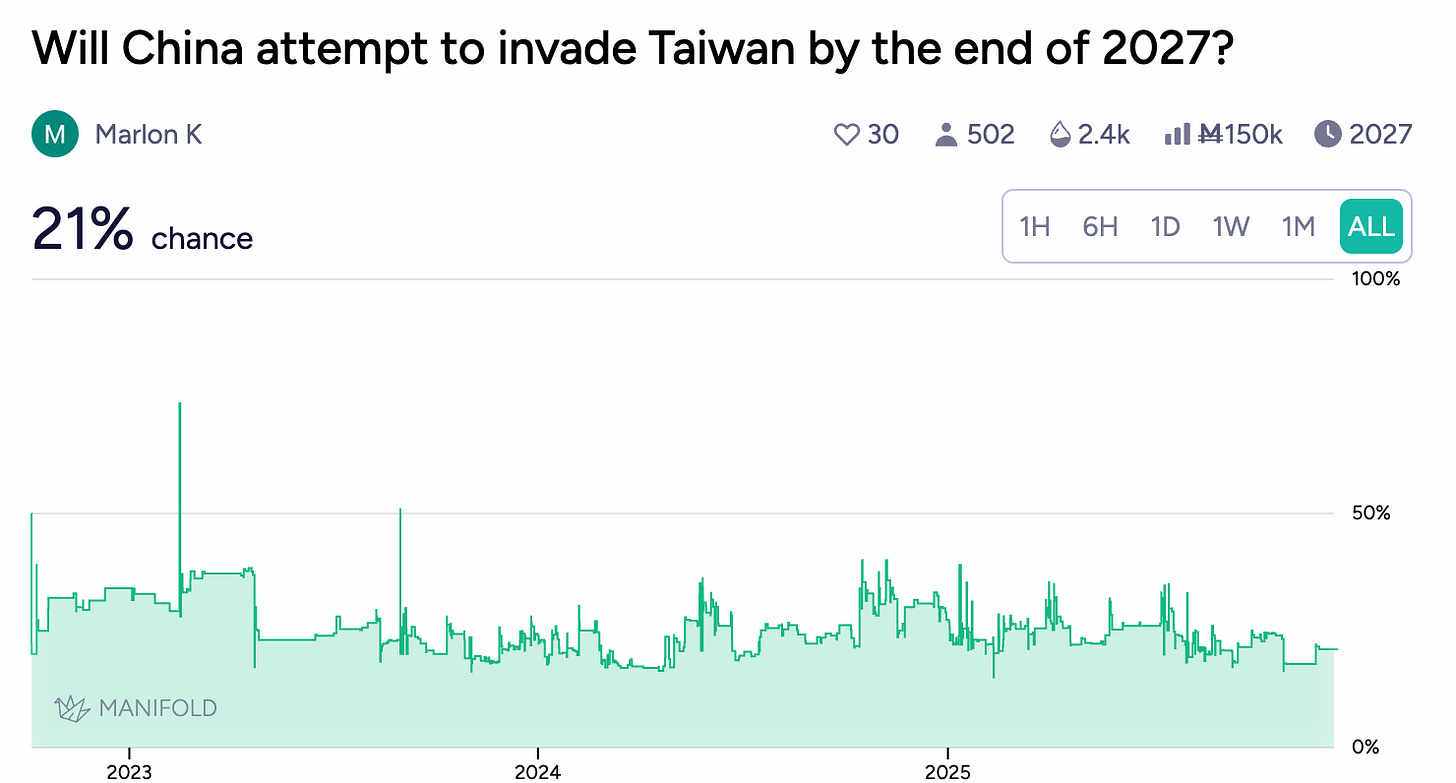

Geopolitical risk markets inching upward while traditional coverage still framed the situation as stable.

Even court-case markets have displayed an uncanny ability to interpret legal signals that outsiders dismissed as irrelevant.

It’s uncomfortable to watch these mechanisms work because they confront a deeply held belief (by many) that expertise should outperform the crowd.

Yet whenever money is on the line and incentives are sharp, the crowd often becomes the expert.

The dynamics behind that efficiency aren’t mysterious. They emerge from a mix of incentives, liquidity, swarm intelligence, and relentless feedback loops.

A trader is forced to update their beliefs in real time. They cannot cling to an outdated view without paying for it. Every new piece of information pushes the market to a new equilibrium, even if only slightly, and the aggregate of these micro-adjustments creates a remarkably sensitive forecasting machine – most of the time at least.

If you ever want a reminder of how powerful decentralized information processing can be, simply scroll through the price history of a major prediction contract during a volatile event.

This is where the connection to equity markets becomes unavoidable. Stocks are auction-driven systems too. They aggregate countless views, time horizons, and emotional impulses into a single price. Investors sometimes forget how brutally efficient this mechanism can be. Prediction markets remind me of that efficiency in its purest form. They show how quickly a market can reprice when incentives are tight, information is diffuse, and participants are forced to confront the implications of being wrong.

But they also hint at something else, something easy to ignore when optimism or conviction runs high. If a simple binary contract with a fixed resolution date absorbs information that efficiently, what does that imply for the far more complex ecosystem of equities?

The lesson is not that markets are perfectly efficient all the time. They never are. The lesson is that markets are far more efficient than many investors are comfortable admitting – most of the time at least –, and that any genuine edge must be earned, not assumed.

So let’s discuss that bridge to the world of stocks, what transfers and what doesn’t.

Before we dive back in, a quick note…

Want to invest in the one edge that compounds forever? Join hundreds of investors sharpening their thinking, avoiding mistakes, and discovering quality before the crowd. Subscribe to CompoundWithRene and become a better investor over time.

The Bridge to Stock Markets

What Transfers?

The most striking overlap between prediction markets and equities sits in the mechanism of price discovery. Both are auction-driven systems that translate fragmented information, shifting beliefs, and heterogeneous motives into a single number.

That number is always provisional, always conditional, and always ready to move when something new arrives.

You see this clearly in prediction markets because the payoff structure is so rigid. A contract will resolve into one outcome, nothing more. That simplicity exposes the continual tug-of-war beneath the surface. Someone buys because they believe the implied probability is too low. Someone sells because they see it as too high. With enough liquidity, these opposing forces create a sensitive, self-correcting signal.

Equities operate on the same principle, even if the visible noise often obscures the underlying logic. Every tick in a stock price represents an update in the market’s collective understanding of a business and its future.

One reason this mechanism works so well is that markets function less like machines and more like complex adaptive systems (something I learned from Michael Mauboussin). They don’t rely on a handful of “lead steers” making the right call but operate through the aggregation of many diverse, often flawed decision rules interacting in real time. When enough independent interpretations collide, the system begins to display emergent intelligence at the collective level, even if individual participants are operating with incomplete information.

Investors bring different models, different emotional states, and different time horizons, yet the auction clears regardless.

So when the market moves against you, it’s because someone else has interpreted the available information differently or weighted it more heavily.

Prediction markets teach you humility here. They demonstrate how fast a market can incorporate news, even subtle news, and how unforgiving the process becomes when incentives are sharp.

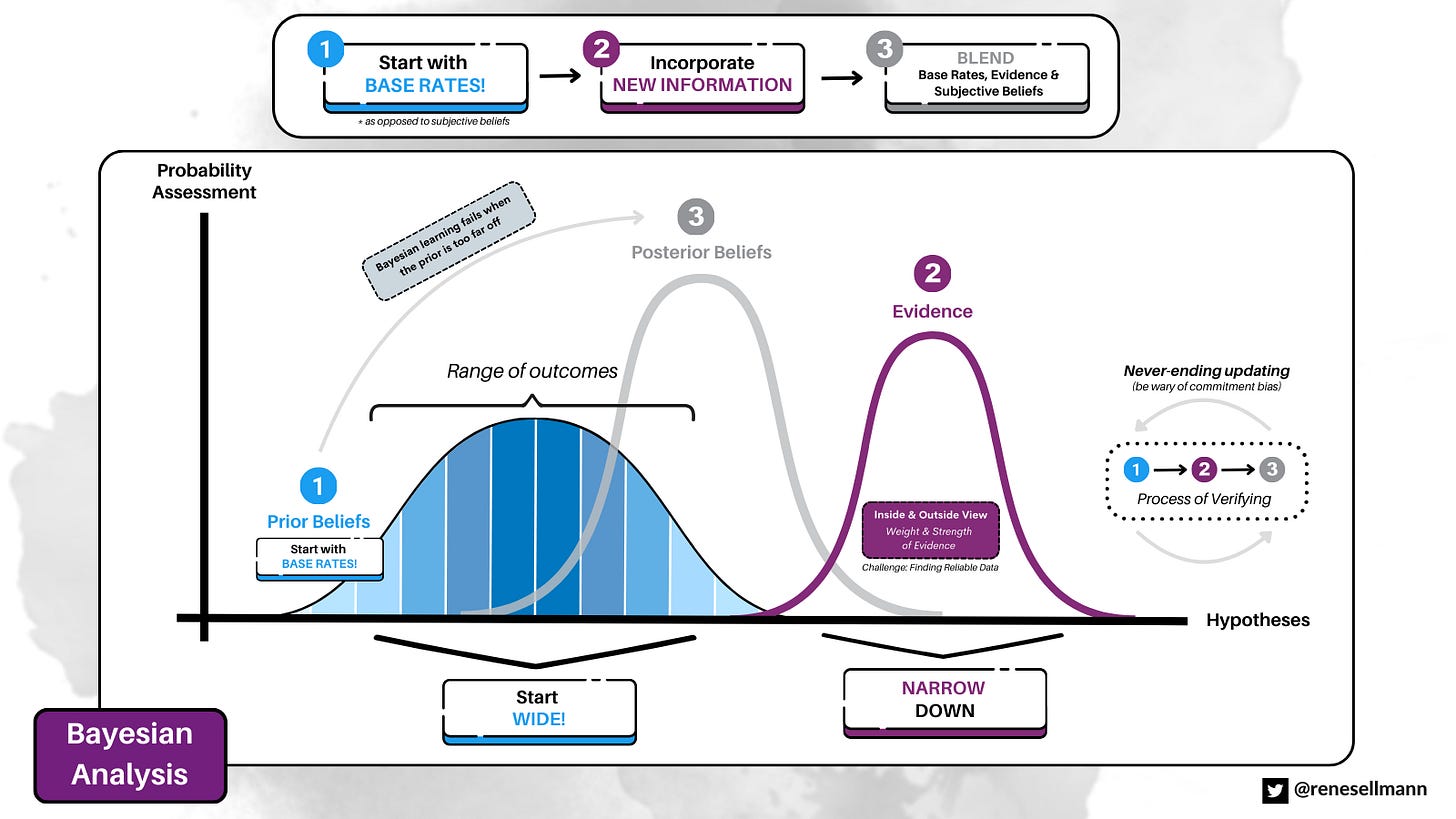

There’s another important transfer: constant Bayesian updating.

Anyone trading a prediction contract quickly learns that anchoring to an early belief is dangerous. The price forces you to reassess whether you want to stand against the crowd’s interpretation of the latest data. Equity markets operate in exactly this way. They reward flexibility and punish intellectual rigidity. Buy and continuously verify. The investor who refuses to update is, over time, the investor who underperforms.

What prediction markets reveal, and what Mauboussin’s work reinforces, is that the intelligence of the market doesn’t depend on the intelligence of each participant. Even simple or poorly calibrated decision rules can, when aggregated, create surprisingly efficient outcomes. The structure of the market itself drives much of the accuracy. This is why even traders who misinterpret individual signals can contribute to a system that, taken as a whole, processes information remarkably well.

What Doesn’t Transfer?

For all of the similarities, the differences between prediction markets and equities are equally revealing.

A prediction contract resolves into a simple yes or no. A binary decision to be made. Stocks don’t. Stocks stretch out across time and contain multiple possible paths, many of which can be right or wrong depending on who is evaluating them.

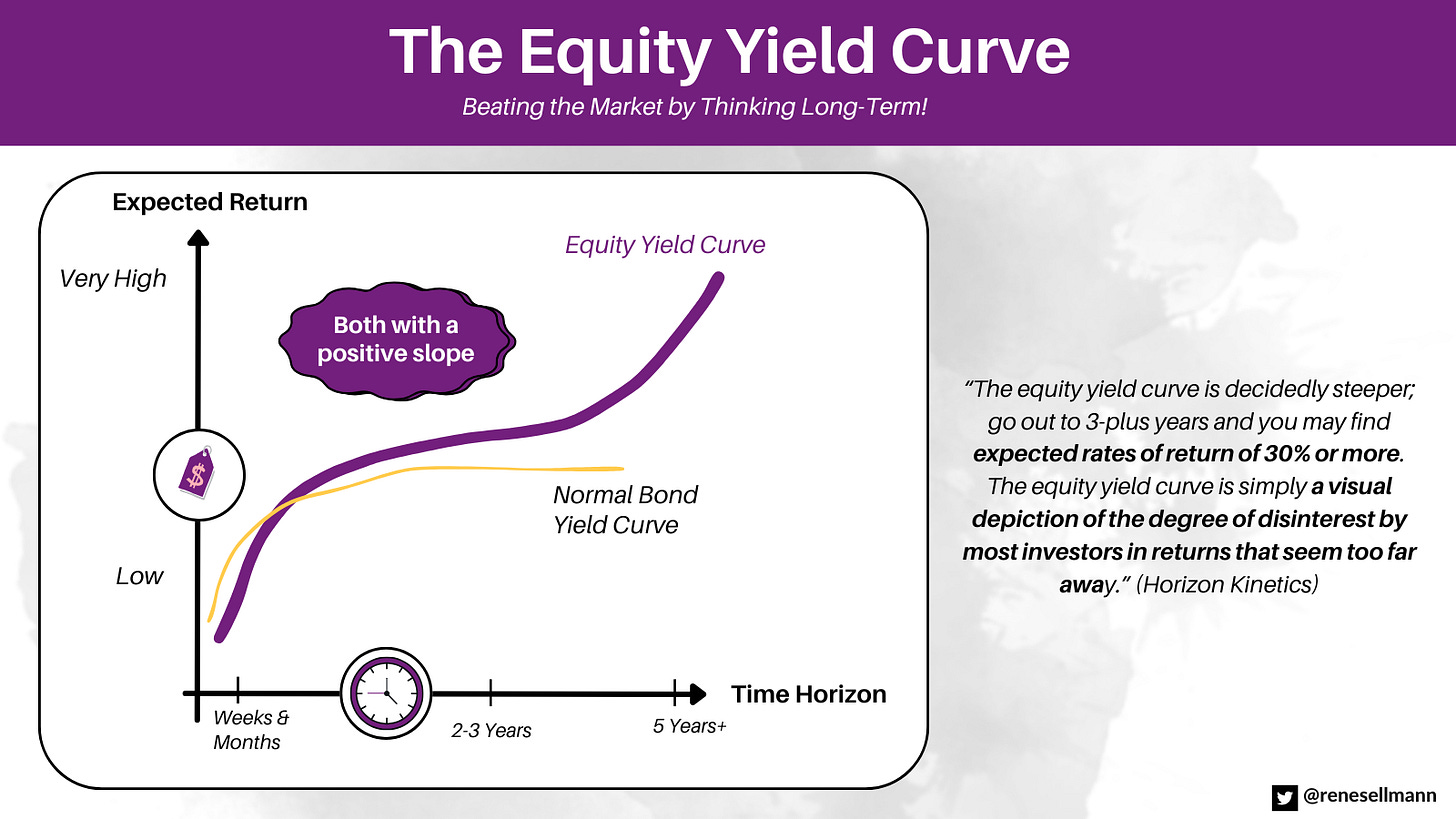

Then there is the question of time horizon. Prediction markets align all participants around a single endpoint. Everyone plays the same game. Equity markets accommodate countless games that coexist without ever merging. A growth investor, a distressed debt analyst, a quant fund, and a day trader can all be trading the same shares for entirely different reasons. Their beliefs don’t converge neatly. They collide and overlap, creating a more layered and sometimes more chaotic price formation process. But in aggregate, they too often create highly efficient pricing dynamics. But nonetheless, a short-term trader and a long-term investor can still be right at the same time; the short seller can profit from a business’s temporary missteps, while a long-term investor can profit from the exact same business reshaping itself over years (exploiting time arbitrage dynamics).

The third major gap is the influence of narrative and momentum. Prediction markets are compressed into a narrow window where the arrival of new information directly forces a repricing. There’s no room for multi-year extrapolation or thematic storytelling or momentum forces. Equity valuations depend heavily on narratives and momentum – at least in the short and medium term. This introduces a layer of path dependency that prediction markets never have to confront.

Fourthly, liquidity also behaves differently. Stock prices can be distorted by forced sellers, leverage unwinding, or institutional constraints unrelated to fundamentals. Prediction markets don’t suffer from those pressures to the same degree. They occasionally lack liquidity, but they don’t see the cascading, multiday – multi-month somestimes – liquidation patterns that show up in equities.

Another gap that prediction markets don’t capture is the inherent nonlinearity of equity markets. Stocks exhibit fat-tailed return distributions, punctuated by long stretches of calm followed by abrupt dislocations.

The Lesson?

The implications for investors are far-reaching. Prediction markets reveal how efficient price discovery can be when incentives, information, and liquidity snap tightly together. If such a simple contract can absorb information with that level of precision, you have to assume that equities, with thousands of intelligent participants and billions of dollars at stake, possess a baseline efficiency that is difficult to overcome. That doesn’t mean opportunities don’t exist. It means the window for exploiting them is narrow, unstable, and rarely obvious in real time.

Understanding what doesn’t transfer is equally important. The complexity of equities creates pockets where inefficiencies can survive.

Time horizon is one of them.

Behavioural resilience is another.

Opportunities often appear when diversity begins to break down. A market with many independent decision rules tends to be stable and efficient. A market where too many investors anchor to the same narrative or react to the same signals becomes fragile. It’s in those moments of reduced diversity that inefficiencies emerge and where disciplined investors can find a genuine edge.

The combined lesson is simple to state yet difficult to internalize. Markets are efficient enough that any durable edge must be earned through genuine insight, selective domain expertise, or an uncommon time horizon.

They are inefficient enough that disciplined investors can still find opportunity. Prediction markets illuminate both truths. They remind you how quickly a market can outrun your conviction, and they underline the importance of knowing exactly where your edge begins and ends.

Credits to Infinite Fund who brought up some of the points discussed here.