As a value investor, one of my core principles is to hold onto long-term compounders for as long as possible—ideally, forever.

The benefits of compounding over decades can be extraordinary, and the fewer interruptions to that process, the better.

However, one factor that often goes underappreciated is how taxes can erode your compounded returns, especially when selling a position.

Taxes should be a significant consideration whenever you're tempted to trade in and out of investments. To quote Charlie Munger: "The first rule of compounding: Never interrupt it unnecessarily."

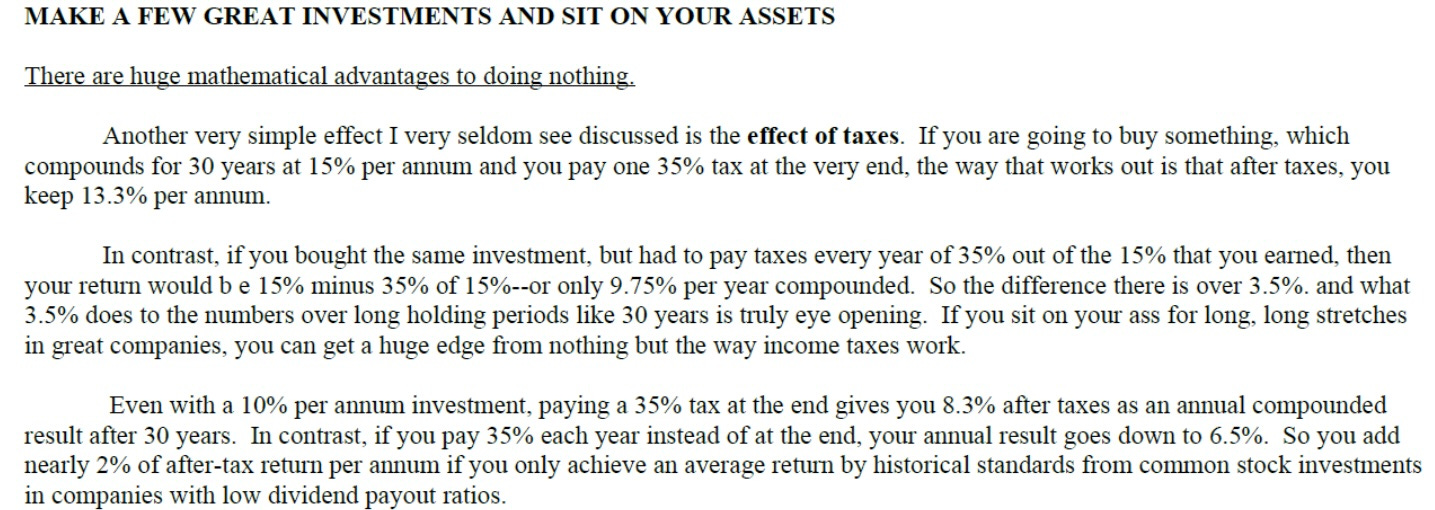

He has frequently highlighted how taxes and transaction costs can diminish long-term returns. For example, a 15% compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) could easily fall below 10% after taxes, depending on your jurisdiction and trading activity:

Recently, I did some calculations that made this point even more striking. Using a simple spreadsheet, I explored how much a stock would need to decline after selling—post-tax—for me to repurchase the same number of shares. The results were eye-opening.

The Cost of Selling: A Spreadsheet Experiment

The premise of my experiment was simple: How much of a price decline would be necessary to buy back the same number of shares after accounting for capital gains taxes?

What I discovered reinforced the importance of being cautious with selling, especially when a stock has appreciated significantly.

Here’s the insight: