The Subtle Art of Capital Allocation

Understanding why the math of buybacks seems deceptively clean, but the art of allocation defies spreadsheets

Capital allocation is one of those topics that is easy to discuss on a basic level, but which many investors find difficult to truly grasp, as it requires a great deal of nuance and critical thinking to assess how value-accretive capital allocation decisions really are/were.

Everyone agrees it matters – a lot! –, but few investors consistently think in terms of opportunity cost – the silent force that shapes the value accretiveness of every decision a management team makes once new cash hits their balance sheet.

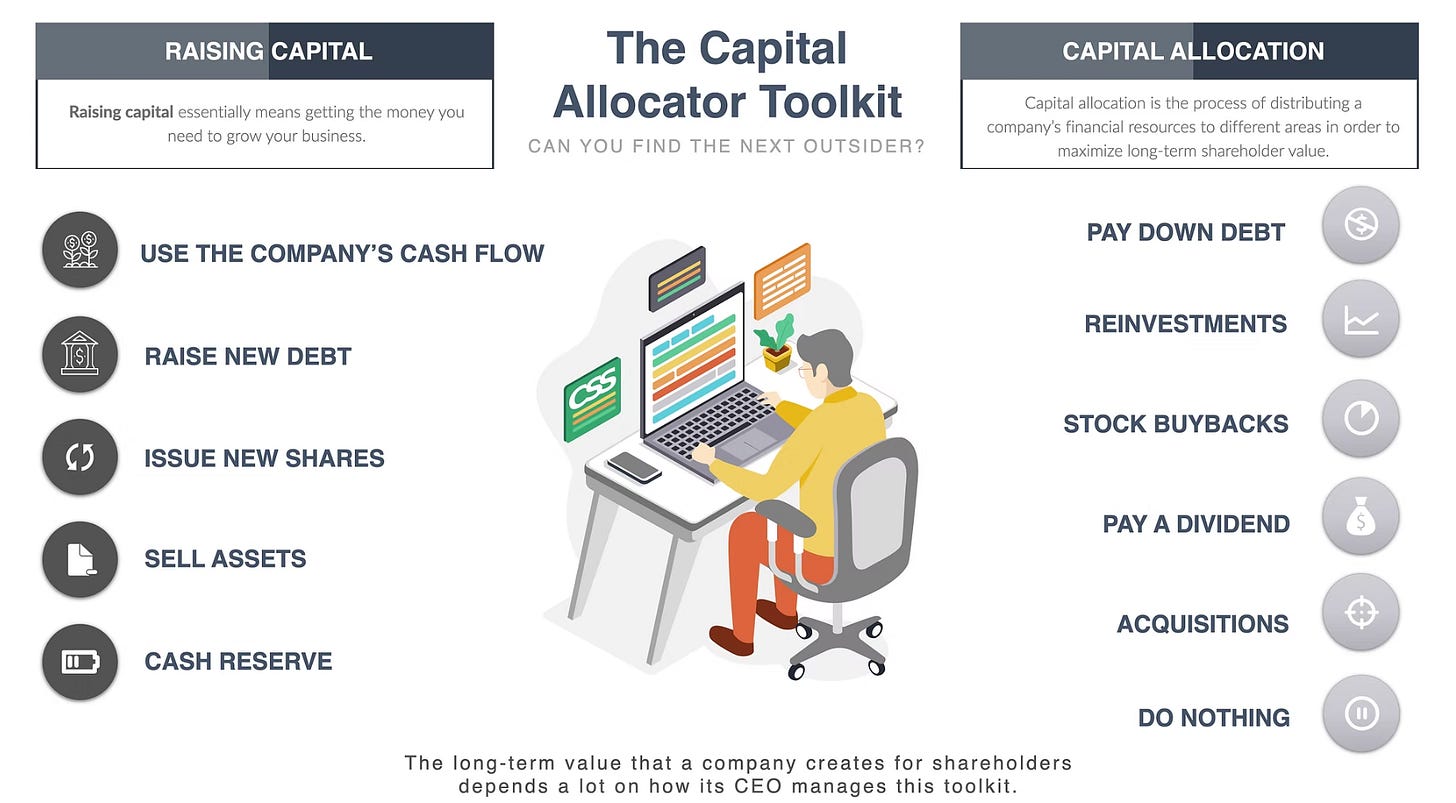

Should they reinvest in the business? Pay down debt? Buy back shares? Raise dividends? On the surface, the options look mechanical, even formulaic. In reality, they require judgment, foresight, sometimes creativity, and sometimes a willingness to do nothing – yes, that’s a capital allocation decision too.

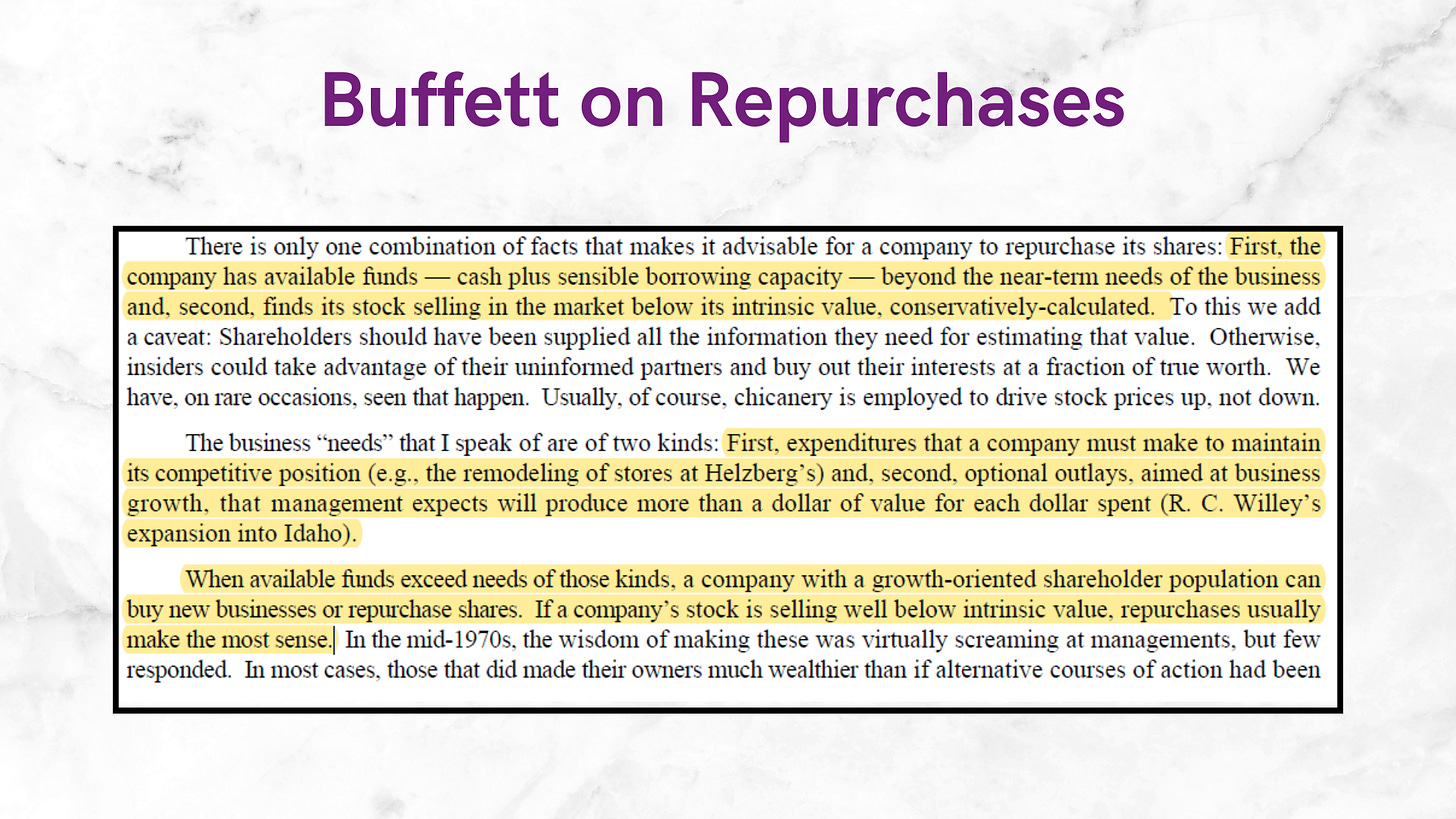

The market tends to reward simplicity. If a company announces a buyback, investors often celebrate. The optics are clean: fewer shares, higher EPS, a tangible signal that management believes the stock is cheap. But as seductive as that narrative is, it can be misleading. A buyback only creates value when the stock trades below intrinsic value. Otherwise, it’s an implicit transfer of wealth from continuing shareholders to those who sell. It’s capital destruction disguised as shareholder friendliness.

Reinvestments back into the business, on the other hand, are messier. The return earned on this allocation of capital doesn’t show up as neatly in quarterly slides. The payback period can be long, the returns uncertain, the outcomes dependent on execution quality, industry structure, and sometimes macro developments management can hardly control. Yet, often, that’s where businesses strengthen their moats, extend their competitive advantages, and plant the seeds for tomorrow’s cash flows.

As investors, we often fall into the trap of treating capital allocation decisions as binary – buybacks versus growth investments, dividends versus M&A. But what really matters is context. Opportunity cost isn’t a static number on a spreadsheet; it’s a concept, often a moving target, shaped by market conditions, valuation, competitive position, and the set of reinvestment options available at any given time.

When I evaluate management teams, I don’t start by asking whether they’re buying back stock. I ask whether they’re thinking like investors – comparing alternatives, ranking opportunities, and deploying capital where the incremental return per dollar is highest after adjusting for risk and durability. That’s a far higher bar than simply repurchasing shares to signal confidence.

“Do they have an intelligent read on intrinsic value and will they consistently buy back shares at attractive discounts to that intrinsic value? That’s another key way to determine whether they are thinking like owners.” Peter Keefe

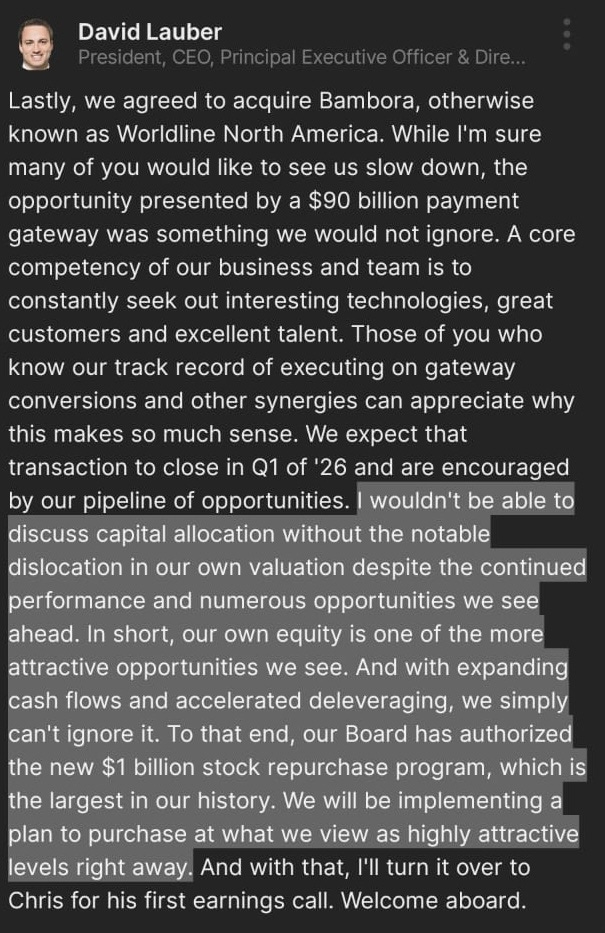

Example below

Ashtead Technology is a good example of this nuance. The company’s share price has been under pressure, and it’s tempting to wish for aggressive buybacks.

But when I look at the reinvestment opportunities in front of them – the ability to strengthen their one-stop-shop moat, expand their equipment, deepen customer relationships, I find myself rooting for internal reinvestment instead; despite the poor recent share performance.

Disclaimer: The analysis presented in this blog may be flawed and/or critical information may have been overlooked. The content provided should be considered an educational resource and should not be construed as individualized investment advice, nor as a recommendation to buy or sell specific securities. I may own some of the securities discussed. The stocks, funds, and assets discussed are examples only and may not be appropriate for your individual circumstances. It is the responsibility of the reader to do their own due diligence before investing in any index fund, ETF, asset, or stock mentioned or before making any sell decisions. Also double-check if the comments made are accurate. You should always consult with a financial advisor before purchasing a specific stock and making decisions regarding your portfolio.

The Opportunity Cost Framework

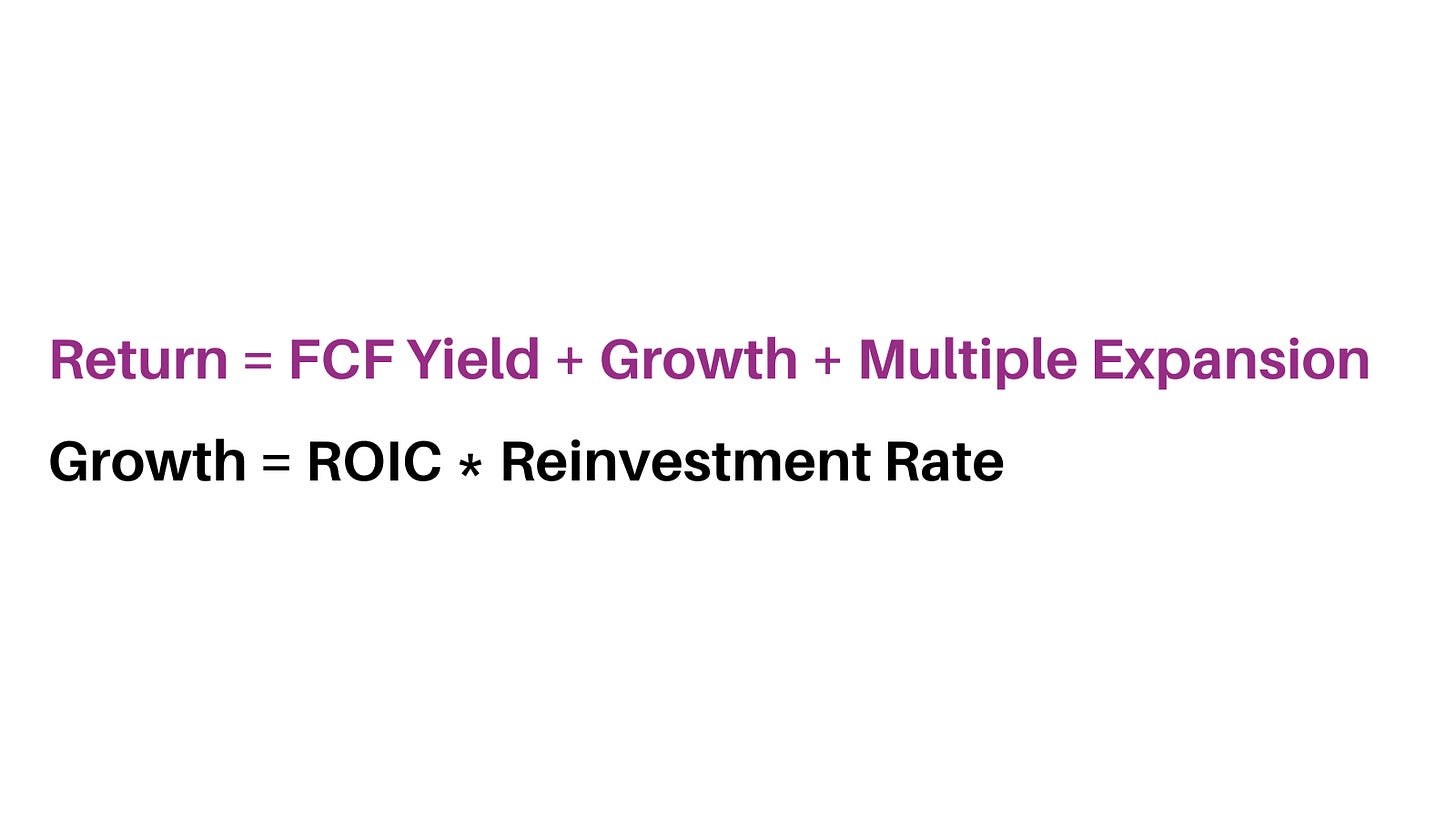

When I think about capital allocation, I think about trade-offs. Every dollar of free cash flow can only be spent once – and every use of that dollar carries an implicit opportunity cost. It’s the return you forgo from the next-best alternative.

In theory, management should always allocate capital to the option with the highest risk-adjusted return.

In practice, this is where things get tricky.

“In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice; in practice, there is.”

The textbook hierarchy goes something like this: first, reinvest in the core business if incremental returns on incremental invested capital (ROIIC) remain attractive; second, pursue strategic acquisitions at attractive prices that enhance the moat; third, pay down debt if leverage is high (+ the interest reduction is a guaranteed return); fourth, repurchase shares if they trade below intrinsic value; and lastly, distribute dividends when no better options exist.

It’s a tidy list. But reality rarely fits the list.

Before we dive back in, a quick note…

Want to compound your knowledge – and your wealth? Compound with René is for investors who think in decades, not headlines. If you’ve found value here, subscribing is the best way to stay in the loop, sharpen your thinking, avoid costly mistakes, and build long-term success – and to show that this kind of long-term, no-hype investing content is valuable.

Sometimes reinvestment opportunities are limited or cyclical. Sometimes management has asymmetric information about intrinsic value. And sometimes, the best capital allocation decision might simply be to wait.

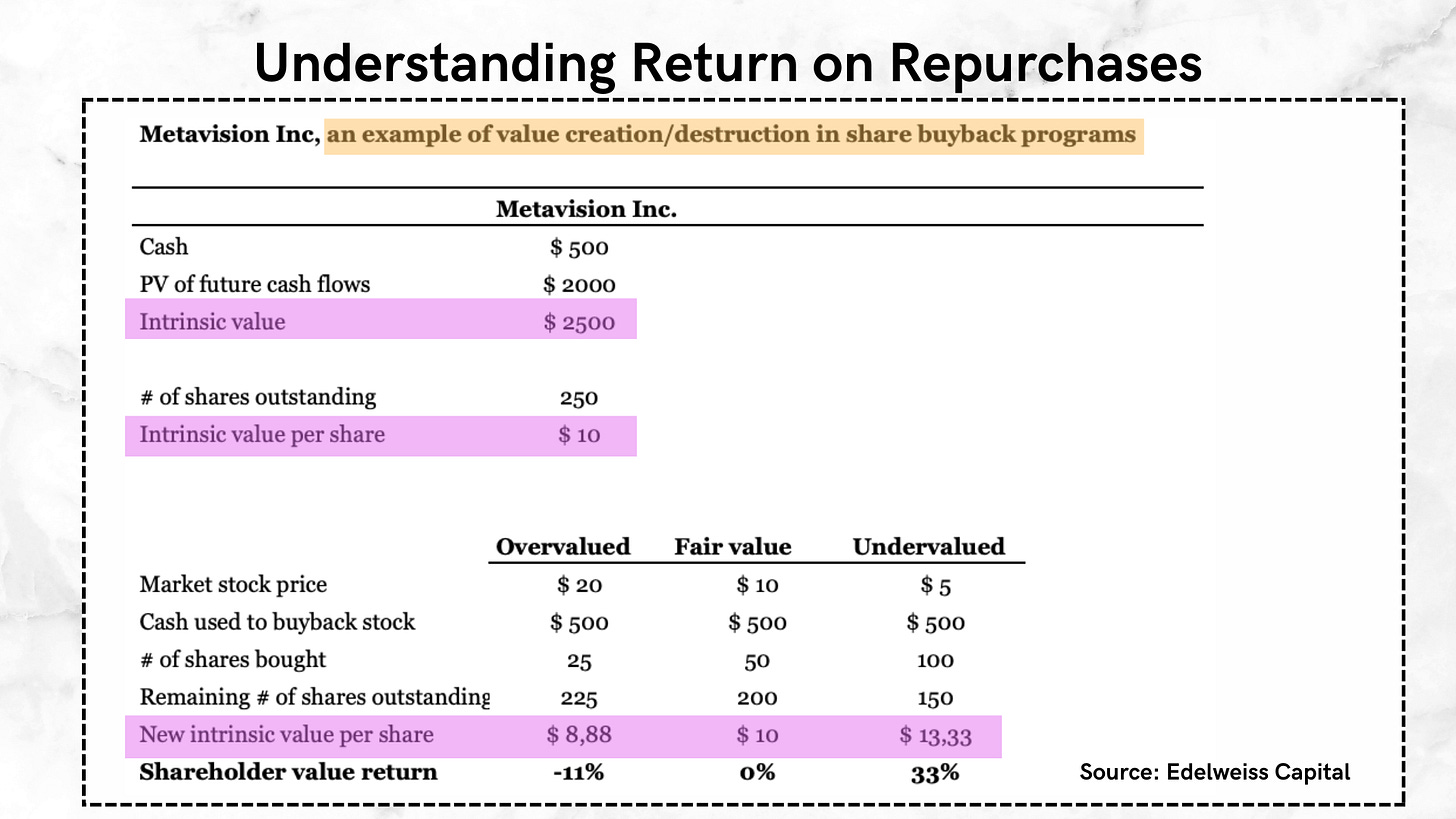

To make this more tangible, I like to share some simple buyback math – and the illustration below of the fictional company “Metavision Inc.” (credits go to Javier Pérez from Edelweiss Capital).

It shows how a $500 buyback can either create, preserve, or destroy value depending on valuation. When shares are overvalued, each dollar used to repurchase stock actually reduces intrinsic value per share. When shares are fairly valued, intrinsic value per share stays roughly the same. And when shares are undervalued, buybacks become a powerful value creation tool.

In the example, buying stock at half of intrinsic value raises per-share intrinsic value by 33%.

On paper, it looks wonderfully precise. But in practice, it’s anything but. Because what drives the entire calculation – intrinsic value – is itself an estimate.

A range, not a point.

A moving target that depends on assumptions about growth, margins, discount rates, and competitive durability (competitive advantage periods (CAP)). And if you define intrinsic value as the present value of all future cash flows, then every input is a guess.

Of course, you can make the spreadsheet sing, but that doesn’t make it true. Bullsh*t in, bullsh*t out.

That’s what makes buyback analysis only deceptively clean. You can model the effects down to the decimal, yet the precision hides uncertainty. A fair-value repurchase today might turn out to have been overvalued six months later if the underlying business stumbles. And if management misjudges their own intrinsic value – or worse, if their incentives are tied to short-term EPS – buybacks can turn into a recurring wealth transfer from continuing shareholders to departing ones.

Reinvestment, by contrast, is less quantifiable, returns even harder to pinpoint, but often reinvestments are more meaningful for long term earnings durability.

“If our goal is to have above-average outcomes, we need businesses to have above-average returns.” – Chuck Akre

Strengthening a moat, building new capabilities, or entering adjacent markets doesn’t always yield an immediate measurable return. It’s qualitative by nature. A company that compounds intrinsic value at a steady rate over decades is usually one that consistently reinvests in itself, even when buybacks look attractive.

This is where critical judgment enters the room again. Opportunity cost in capital allocation isn’t just a number; it’s THE framework for thinking about trade-offs under uncertainty.

A dollar spent on buybacks at a 15% implied return might look tempting, but if reinvesting that same dollar in product innovation or network expansion expands the competitive advantage period by another five years, increases the defensibility of the business, thereby reducing downside risk and increasing risk-adjusted returns, well then … this investment may be the superior choice.

Depending on your financial goals and circumstances, longevity of return often trumps magnitude.

Or as Pabrai once put it, “return of capital is more important than return on capital.”

The best management teams – the truly great capital allocators – don’t chase the highest short-term yield. They allocate based on the durability, scalability, and strategic optionality of each dollar spent. And that’s something a spreadsheet alone can’t tell you.

“And over this last year, I feel like we pulled off a pretty incredible feat. We’ve taken down our price point by about 15%, effectively expanding our economic moat quite incredibly. And at the same time, we boosted the growth of volumes and customer holdings.“ Kristo Käärmann on Wise’s recent quarterly call

That’s why, in the case of Ashtead Technology, I lean toward reinvestment. The company operates in an industry where equipment breadth, scale, and customer trust matter immensely. Strengthening those through organic or inorganic investment likely produces more sustainable returns than simply shrinking the share count. Buying back stock might make near-term optics cleaner and the chart look less painful, but reinvesting builds the foundation for multi-year compounding.

When Buybacks Make Sense – and When They Don’t

There’s a tendency among investors to treat buybacks as a universal good. The logic is intuitive: fewer shares mean higher ownership per share, higher earnings per share, and a signal that management believes the stock is undervalued. But like most things in investing, context matters. As shown, buybacks can be either the most accretive or the most destructive use of capital – and sometimes, they’re neither. They’re just a way to smooth the ride.

Buybacks make sense when two conditions align. First, the stock must trade at a meaningful discount to intrinsic value. Second, the company must lack reinvestment opportunities offering comparable or better risk-adjusted returns. That combination is rare, because truly great businesses often have abundant ways to reinvest capital at high incremental returns.

The companies most capable of compounding capital internally are often the ones least likely to benefit from buybacks.

That doesn’t mean buybacks never have a place. When a company’s share price has fallen below intrinsic value due to temporary pessimism – a cyclical downturn, a misunderstood earnings miss, or market-wide de-risking – repurchases can also serve as a defensive mechanism, providing short- to mid-term stability by absorbing selling pressure, countering elevated short interest, or signaling internal confidence when sentiment has swung too far. Evolution Gaming as a prime example immediately comes to my mind.

In that sense, buybacks can act as a pressure valve, keeping the share price from detaching too far from fundamentals.

Of course, there’s also a governance layer to all this. When a company trades at a depressed valuation and lacks an anchor shareholder, it becomes vulnerable to opportunistic takeovers.

That’s when capital allocation and corporate integrity intersect. Management must resist the temptation to entertain offers that undervalue the business simply because sentiment is weak. In those situations, alignment of interest and clarity of purpose matter even more than precise capital allocation math.

Ultimately, great capital allocators don’t think in rigid categories. They don’t see buybacks, reinvestment, or dividends as right or wrong. They view them as tools – each with a different purpose and optimal use depending on valuation, opportunity set, and time horizon. The best managers flex between them fluidly, guided not by what pleases the market but by what compounds intrinsic value per share over time.

PS: Here’s a cheat sheet I once created for my mentoring program:

Has AT decided to allocate capital back into the business? Or is it just your preference? Worth going deeper into AT?