The Paradox of the Brokerage Business: A Business That Shouldn’t Work (But Does)

A counter-intuitive look at why some competitive industries destroy value while others compound it endlessly

Every time I study an industry, I try to remind myself that where you play matters just as much as how you play. Some industries are built on sand, others on granite. You can be the sharpest operator in the world, but if the economics of the playing field are weak, you’ll still end up fighting a losing battle.

That’s why one of my favourite mental models comes straight from Charlie Munger: start with the don’ts.

“All I want to know is where I’m going to die,” Munger once said, “so I’ll never go there.”

It’s an odd way to think about investing, but it’s deeply practical. Before chasing what looks exciting, I try to identify the businesses and sectors where structural economics make long-term success nearly impossible.

Airlines, auto manufacturing, shipping – these have historically been graveyards of capital.

The best investors I’ve studied – from Munger to Terry Smith – understand that avoiding value-destroying industries is often a key driver of outstanding results.

Over the years, I’ve built my own “industry avoidance list.” It’s filled with fields where differentiation is minimal, pricing is dictated by competition rather than value, and capital requirements are punishing. If you can’t achieve durable advantages in such environments, even competent management teams can only do so much.

That’s what makes the brokerage business such a fascinating paradox.

At first glance, it looks like it should not be a great business. It’s crowded. Differentiation between players is (often) marginal. Fees have collapsed to zero. Most brokers offer access to the same markets, similar interfaces, and near-identical order execution. If you’re a retail investor in Germany, for instance, does it truly change your experience whether you trade through flatexDEGIRO, Trade Republic, or Comdirect? For the vast majority of users, probably not.

So why do brokerage firms keep minting money and creating shareholder value while so many other competitive industries destroy it?

The paradox deepens when you remember how price wars usually end. In industries with little product differentiation, competition drives prices toward cost. Margins compress, returns fall, and capital flees. That’s capitalism doing what it does best – discipline inefficiency.

Yet in the brokerage world, despite years of zero-commission trading and a flood of fintech entrants, the biggest players remain immensely profitable. ROIIC high. Their margins rival luxury-goods companies, not commodity businesses.

This isn’t supposed to happen…

On paper, brokers should behave more like airlines: brutal competition, low switching costs, and constant pricing pressure. But that’s not what we see. Instead, the average brokerage platform operates with gross margins north of 80 percent. Interactive Brokers keeps making headlines by posting higher and higher EBT margins.

When I first started comparing these two worlds – the brokerage business and the airline business – the contrast felt almost absurd. One industry is a textbook case in value destruction; the other, an overlooked compounding machine.

And that contrast reveals something fundamental about how capitalism works: competition isn’t automatically bad. It depends on where it hits the system.

So that’s the puzzle I want to unpack. Why is the brokerage business – so crowded, so price-competitive – still one of the best business models in the financial world? Why has it resisted the fate of airlines and other “bad neighborhoods” of capitalism? And what can we, as investors, learn from this paradox when evaluating industries more broadly?

In the next chapter, I’ll start with the control group: the airline industry. Because to appreciate why the brokerage model works so well, it helps to first revisit a sector that’s been failing in plain sight for over a century.

Before we dive back in, a quick note…

If you’re reading this as a free subscriber and finding value in this kind of deep, idea-by-idea analysis, consider upgrading to the full version. I write these posts for long-term thinkers who want more than earnings call recaps and press-release summaries. If that’s you, I’d love to have you on board.

PS: Using the app on iOS? Apple doesn’t allow in-app subscriptions without a big fee. To keep things fair and pay a lower subscription price, I recommend just heading to the site in your browser (desktop or mobile) to subscribe.

Here’s a quick overview of what I’ll explore in this post:

Why industry selection matters as much as stock selection – and why avoiding structurally weak industries often delivers better long-term results than finding the next “winner.”

The paradox at the heart of the brokerage business – how a sector with little differentiation, shrinking fees, and dozens of competitors still produces exceptional returns on capital.

A deep look at the airline industry as a cautionary tale – why decades of cut-throat competition, high fixed costs, and low switching barriers have made airlines serial destroyers of shareholder value.

What makes brokerage competition different

The psychology and economics of customer stickiness – understanding inertia, trust, regulatory frictions, churn rates and customer lifetime value

The superior unit economics behind the scenes – exploring how brokers benefit from multiple layers of high-margin revenue streams

The role of trust, regulation, and brand – why reputation, licensing, and compliance systems act as quiet barriers to entry in a supposedly commoditized market.

What this paradox teaches investors about competition – the difference between competition that compresses margins and competition that expands the pie.

Broader lessons for identifying great industries – how to recognize when a crowded space hides a scalable, compounding business model beneath the noise.

A Textbook Case in Destruction: Airlines as the Contrast

If there’s one industry that captures everything Munger warned us about, it’s airlines. It’s almost poetic in how consistently it has destroyed shareholder value. You could fill libraries with post-mortems on failed carriers, bankruptcies, and restructurings. The faces on the tail fins keep changing, but the economics remain the same.

Buffett’s famous quip that a farsighted capitalist should have “shot Orville Wright at Kitty Hawk” wasn’t just a joke – it was a recognition of structural reality.

“If a capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk back in the early 1900s, he should have shot Orville Wright. He would have saved his progeny money. But seriously, the airline business has been extraordinary. It has eaten up capital over the past century like almost no other business because people seem to keep coming back to it and putting fresh money in. You’ve got huge fixed costs, you’ve got strong labor unions and you’ve got commodity pricing. That is not a great recipe for success. I have an 800 (free call) number now that I call if I get the urge to buy an airline stock. I call at two in the morning and I say: ‘My name is Warren and I’m an aeroholic.’ And then they talk me down.“ - Buffett in an interview with The Telegraph

Even as passenger volumes soared and technology advanced, almost every dollar of profit the industry ever produced eventually evaporated into higher input costs, new aircraft orders, or fare wars.

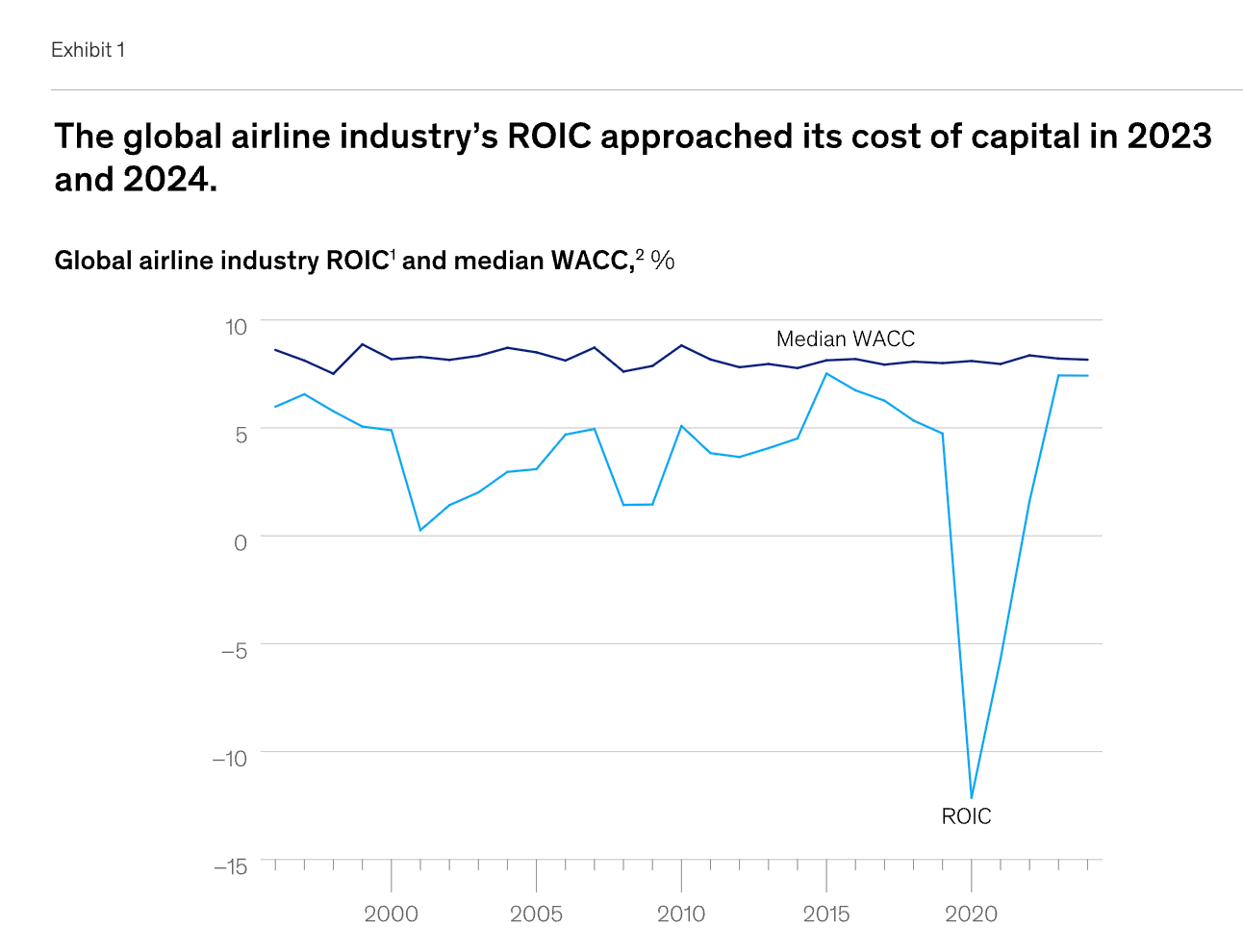

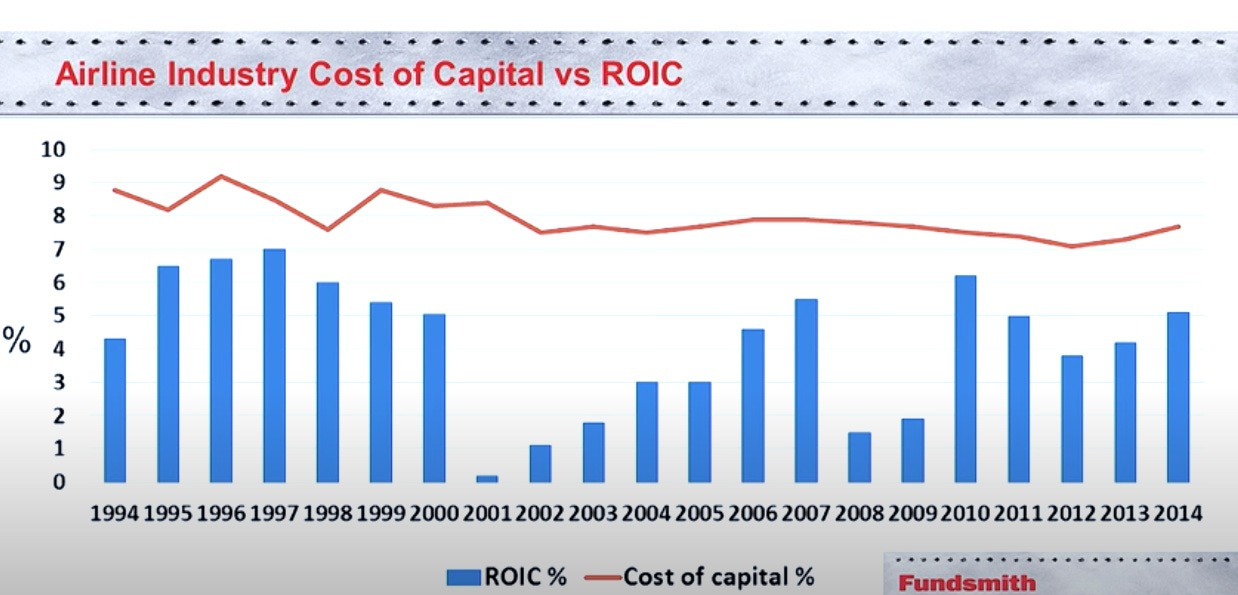

McKinsey once calculated that global airlines, over decades, earned a cumulative negative economic profit:

“Airline sector ROIC in aggregate has been below its cost of capital since at least 1996, which is the earliest data point in our research (Exhibit 1). Many of the structural factors underlying this poor result remain: Airline passengers are typically very price sensitive, the industry features strong competition paired with low barriers to entry and high barriers to exit, and the regulatory landscape can pose challenges to consolidation. But in 2023 and 2024, results improved. The annual differences between ROIC and WACC, at the sector level, were among the narrowest we’ve seen in the history of our research.“ – McKinsey “Can the global airline industry continue its climb?“

Imagine that: an industry that connects the world, carries billions of people, and yet, after all that effort, barely covers its cost of capital.

The reasons are brutally simple. Airlines sell a commodity product. A seat from New York to London is largely the same whether you fly Delta or British Airways. For most travelers, the decision comes down to schedule and price. That price sensitivity sets off a destructive chain reaction. The moment one carrier cuts fares to fill planes, others must match or lose load factor.

The result? An industry-wide race to the bottom.

Layer on top of that the capital intensity. Planes are expensive, airports charge fees, maintenance is constant, and fuel prices swing wildly. You can’t simply stop flying your aircraft when demand softens – you still pay for leases, crews, insurance, and hangars. And when recessions hit, passenger volumes fall while fixed costs stay anchored. It’s a perfect storm for financial pain.

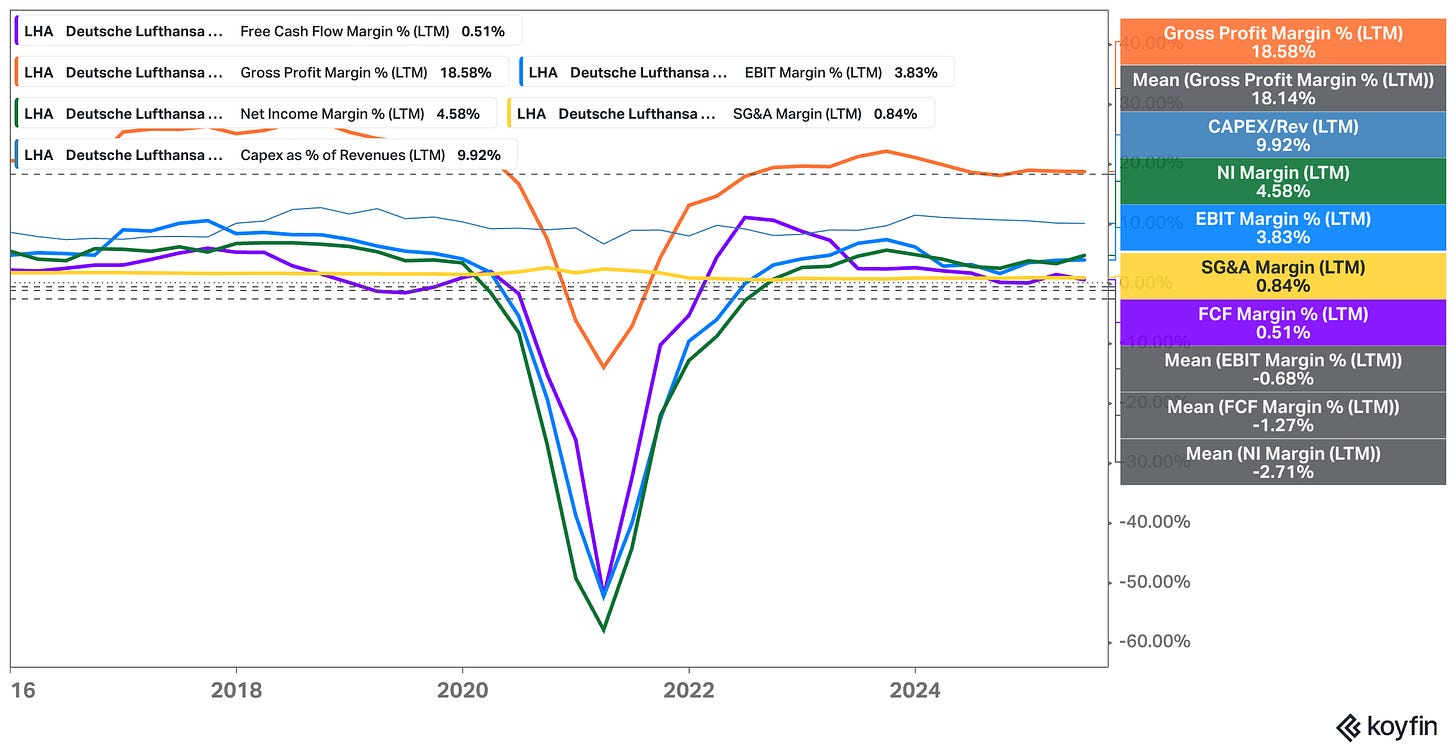

Then there’s labor. Pilots, cabin crew, and mechanics are skilled, unionized, and rightfully demand strong pay. So when times are good, wages rise; when times are bad, airlines can’t cut them fast enough. Few industries have a cost base so rigid yet a revenue line so volatile. It’s no wonder the average airline’s net profit margin hovers around one or two percent in good years and dives into red ink during downturns.

Even consolidation hasn’t saved them. The U.S. airline market today is dominated by four major carriers – and still, the combined group barely manages to earn its cost of capital.

In theory, fewer players should improve discipline. In practice, new low-cost entrants pop up every few years, restart the fare wars, and the cycle begins again.

Terry Smith from Fundsmith summed it up elegantly:

“But don’t all companies create value for their shareholders? Sadly not. There are some industries which are prone to make returns below their cost of capital much or all of the time, such as the airline industry which has probably not created value for shareholders throughout most of its existence. Surely if a whole industry just keeps destroying value, why would anyone invest in it? It seems hope springs eternal for some investors. They invest in companies which do not make adequate returns and so destroy value because they hope they will change – that a change of management, an upturn in the business cycle, a takeover or industry consolidation will alter this fundamentally poor characteristic. Of course it rarely does, but that’s not the only problem. […]” - Fundsmith - Why You Should Invest in Good Companies

His point wasn’t merely academic. Investors repeatedly convince themselves that this time will be different – that consolidation, or new fuel-efficient aircraft, or dynamic pricing will finally make the business rational. But the physics of the industry don’t change. Each plane still costs millions, each seat still needs filling, and each ticket is still judged by price.

The airline business is, in many ways, capitalism’s cautionary tale. It’s not that the companies are poorly run – many are operational marvels. It’s that the structure of the industry traps even competent players in mediocrity.

And that’s what makes the comparison to stock brokerage so instructive. On the surface, both industries appear similar: many competitors, seemingly commoditized services, and intense pricing pressure. Yet one perpetually destroys value while the other creates (and compounds) it.

Why? Because in the brokerage world, competition plays out on a completely different terrain.

Airlines compete every day for each ticket sold. Brokerages compete once – at the moment of customer acquisition – and then enjoy years, sometimes decades, of loyalty and recurring economics. Airlines need to fill every seat on every flight, every day. Brokers can scale their business infinitely without the same variable cost drag. Airlines sell perishable capacity. Brokers sell access and trust.

Understanding this distinction is key to seeing why fierce competition in some industries can be fatal, while in others it’s merely a surface illusion.

Why Brokers Are the Exception

Once you’ve spent enough time studying industries like airlines, shipping, or autos, it’s easy to develop a cynical reflex: when you see lots of competition and little differentiation, you assume returns must be poor.

And yet, the brokerage business refuses to obey that rulebook. Despite hundreds of players globally and relentless competition, many brokers are extraordinarily profitable.

That shouldn’t make sense – but it does once you look under the hood.

The full story starts here:

The rest of this post covers the structure of the brokerage business. If you’re serious about sharpening your investing edge, the full post (and all my previous premium content, including valuation spreadsheets, deep dives (e.g. well-known mid- and large caps such as LVMH, Duolingo, Meta, Edenred as well as more hidden gems such as Tiger Brokers, Digital Ocean, Ashtead Technologies, InPost, Timee, and MANY more) and powerful investing frameworks. is just a click away. Upgrade your subscription, support my work, and keep learning.

Annual members also get access to my private WhatsApp groups – daily discussions with like-minded investors, analysis feedback, and direct access to me.

PS: Using the app on iOS? Apple doesn’t allow in-app subscriptions without a big fee. To keep things fair and pay a lower subscription price, I recommend just heading to the site in your browser (desktop or mobile) to subscribe.