Meta Platforms (META 0.00%↑) has been on an absolute tear. The stock recently achieved a record-breaking 20-day winning streak, surpassing all individual stock records in the S&P 500.

Investor sentiment is overwhelmingly positive—Twitter user borrowed_ideas recently wrote, "Of my almost seven years of being a Meta shareholder, I do not recall investors being so nearly unanimously positive about the company’s prospects."

Given this “euphoria,” a contrarian investor might instinctively consider trimming his/her position or even selling. After all, base rates suggest that stocks rarely sustain this level of momentum for long. Meta’s meteoric rise—according to Tho Brkan, a 154% CAGR from its Q4 2022 bottom—seems unsustainable as an expansion of the valuation multiple has been a significant driver of Meta’s recent gains.

Yet, what if traditional valuation frameworks are missing something?

This brings us to a fascinating concept introduced by value investor Mohnish Pabrai—the Spawner Framework. Certain businesses possess a unique DNA that allows them to continuously "spawn" new revenue-generating businesses, making traditional valuation models largely irrelevant.

Companies like Amazon (AWS), Alphabet (Google Cloud, Waymo), and Microsoft (Azure, LinkedIn, Gaming, OpenAI investment) have successfully built billion-dollar businesses outside their core operations. These firms are not just “operating businesses” but “business creation engines”—true spawners.

So, the key question is:

Is Meta Platforms developing into a spawner as well?

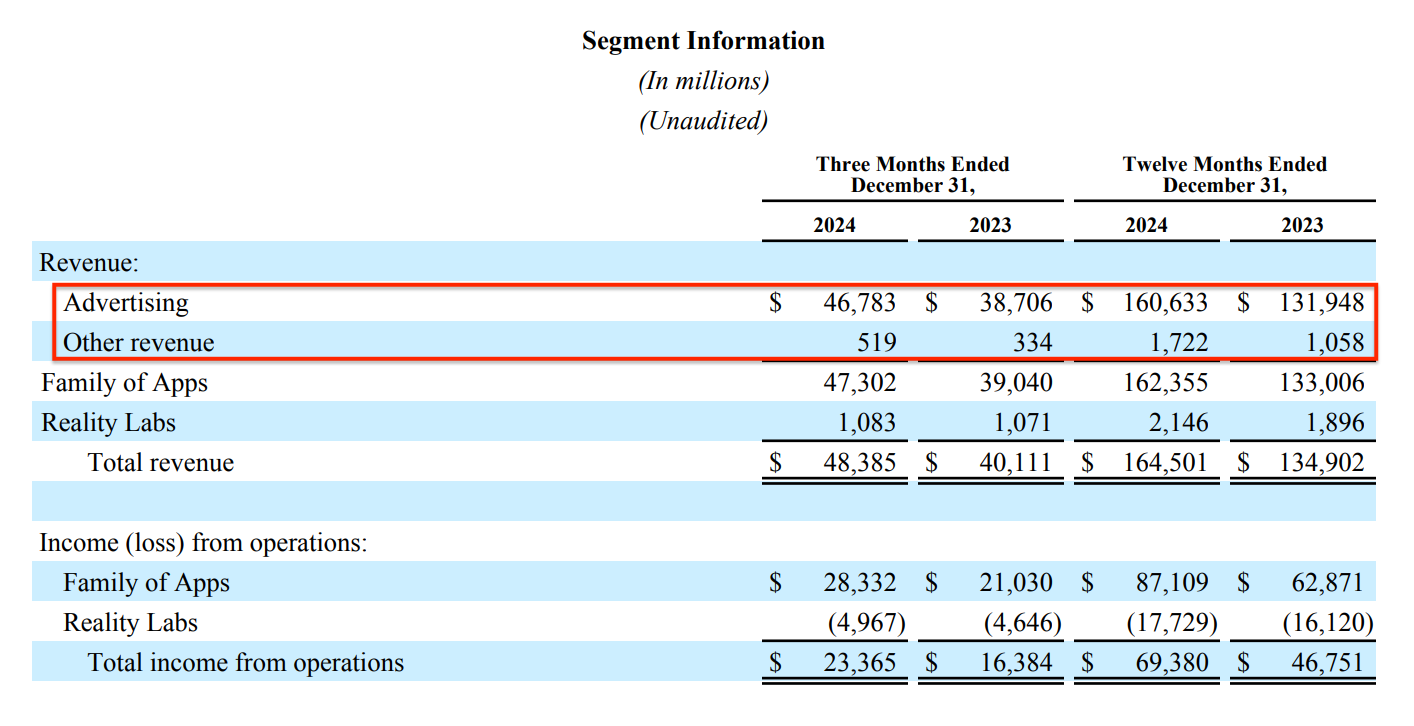

At first glance, Meta doesn’t seem to fit the mold. Its core business—digital advertising—still accounts for over 99% of its revenue and practially all of Meta’s profits.

Surely, Zuckerberg’s company has made some high-profile acquisitions (Instagram, WhatsApp, Oculus), but it has yet to create a wholly new, unrelated business that meaningfully contributes to its financials.

However, if we examine Meta more closely, we see signs that Zuckerberg & Co. are actively "learning" the spawner DNA—from aggressive cloning tactics to bets on artificial intelligence and even humanoid robotics.

Thus, in this post, we’ll explore:

What makes a business a spawner?

Where Meta fits within the spawner framework.

Whether Meta can successfully evolve into an adjacent or non-adjacent spawner.

What this means for investors trying to value the stock.

If Meta is indeed becoming a spawner, then traditional valuation models—based purely on its current business—may be missing a huge optionality component.

(FULL DISCLAIMER: As of the time I’m writing this, I own shares in Meta and Meta represents the largest position in my portfolio. Hence, I’m clearly biased!)

1) The Spawner Framework: How Some Companies Defy Traditional Valuations

Value investor Mohnish Pabrai introduced the Spawner Framework in a presentation at the Guanghua School of Management, defining spawners as companies that continuously create or acquire new businesses—providing multiple avenues for growth.

These businesses operate beyond traditional valuation models because their future potential often lies in ventures that don’t yet exist.

Pabrai categorizes spawners into several types. First, Adjacent Spawners are companies that expand into closely related business areas. Amazon is a classic example, starting as an online bookstore before methodically adding new categories, while Starbucks extended its brand into packaged consumer goods like bottled Frappuccinos and at-home coffee.

Then there are Embryonic Spawners, which acquire small businesses and nurture them into major successes. IAC follows this approach by acquiring and scaling internet businesses like Match.com and Vimeo.

Another category is Cloner Spawners, companies that replicate successful ideas and make them their own. Microsoft has a long history of this strategy, acquiring Forethought and turning it into PowerPoint, launching Internet Explorer to challenge Netscape, and creating Azure as a direct response to AWS. Meta has also followed this playbook, cloning Snap’s Stories, adopting TikTok’s short-form video format, and launching Reels to compete in the space.

More ambitious are Non-Adjacent Spawners, companies that build entirely unrelated businesses. The most famous example is Amazon Web Services (AWS), a cloud computing platform that became a multi-billion-dollar enterprise despite having no direct connection to Amazon’s e-commerce business.

The rarest of all are Apex Spawners, firms that exhibit all four spawner characteristics. Google is an example, launching Chrome as an adjacent business, acquiring Android and YouTube as embryonic ventures, copying competitors like Facebook with Google+ (admittedly an unsuccessful endeavor), and expanding into unrelated fields like cloud computing and autonomous vehicles with Google Cloud and Waymo. Amazon, too, fits this mold with its ever-expanding portfolio, from its marketplace growth and acquisitions like Whole Foods to its cloning efforts with Amazon Fresh and its non-adjacent bet on AWS.

Most businesses, however, are non-spawners—even highly successful ones.

These companies focus solely on their core business and prefer returning excess cash to shareholders through buybacks, dividends, or reinvestments in the core business that provide high visibility in terms of ROI rather than venturing into new revenue streams with hard-to-predict returns on incremental investments.

Spawners, by contrast, have an inherent hidden optionality—they create value that traditional financial models struggle to quantify. Investors tend to focus on tangible, easily measurable metrics like revenue, earnings, and cash flow, but history has shown that intangible factors—such as brand strength, research and development investments, and market positioning—often drive the most significant returns.

Pabrai also points to a crucial tax advantage enjoyed by spawners. By continuously reinvesting their pre-tax earnings into new initiatives, these companies reduce taxable income and extend their reinvestment runway. Amazon is a textbook case, as it spent years reporting minimal earnings while aggressively reinvesting its cash flows into new businesses, allowing it to scale at an unprecedented rate.

In investing, what you can’t see often matters more than what is immediately visible.

The concept of optionality is difficult to quantify, but it can be a game-changer in determining a company's future value.

This brings us to the key question: where does Meta fit within this framework? Is it already a spawner, or is it still in the process of developing the DNA needed to join the ranks of companies like Amazon and Google?

2) Meta’s Evolution Through the Spawner Lens

At first glance, Meta Platforms doesn’t fit the classic definition of a spawner. The company’s core business—digital advertising—still accounts for over 99% of its revenue, and it hasn’t organically expanded into adjacent or non-adjacent industries the way Amazon or Google have.

Yet, a deeper look reveals that Meta already exhibits some key spawner traits and may be in the process of developing others.