Learning from Henry Ellenbogen

A practitioner’s lens on small caps, repeat founders, and physical infrastructure

A few days ago, I came across the fairly new Invest Like The Best episode featuring Henry Ellenbogen, founder of Durable Capital Partners.

I’m of course biased – I love the show and I love learning from people who treat investing as a lifelong puzzle rather than a quarterly performance sport. But even adjusting for bias, this was an extraordinary conversation. One of the best of the year.

Maybe the best of 2025 on investing.

Ellenbogen didn’t start in finance. He studied organic chemistry, history, and technology, and spent years working in politics. That unusual path ended up giving him an advantage later, because he learned to study companies like ecosystems and leadership like a repeatable edge.

In this conversation, he touches on themes that matter more now than ever: second-time founders, hidden physical moats, the interplay between AI and real-world infrastructure, how to build positions when conviction grows, and the brutal opportunity cost of misallocating attention.

I left the episode with pages of notes. I picked five core ideas from the conversation that felt most valuable to me. This post is my attempt to actually internalize them. Writing them down forces me to slow down, think harder, and remember better. It’s the same reason Ellenbogen built a memo culture into his firm. You can hear something smart. Or you can absorb it. The second option takes longer. But it compounds too.

“We’re a writing culture, because at the end of the day, human beings are innately human. When we are involved in something, it’s very hard to have that executive distance that you need to do to really hold yourself accountable to what you thought and actually hold the companies accountable to what you would like them to do. Especially since we really do know the people we invest in, and we invest in really high quality interesting people, and we’re deeply rooting for everyone to succeed. […] When we write an investment memo, it’s in service of our investment philosophy, making sure we’ve done the work and we can clearly articulate why is a company competitively advantaged or will it be? What would it have to do? Why is this operating culture excellent or why does it have the seeds of an excellent operating culture? And why does this leader think like an owner where they can basically make the business better, which we define as gaining market share through cycle? […] That’s our investment memo.“

The sections that follow are written for the same kind of reader I am – someone who wants frameworks that can be applied to improve one’s process, and lessons that stick around during calm and turbulent market times. Let’s get into the first one.

Insight #1: Power Law Distributions & Hunting for the Real Outliers

One of the most clarifying moments was how direct Ellenbogen is about the shape of outcomes in public markets. While managing T. Rowe Price’s New Horizons Fund, he went into the archives to decode half a century of performance. The conclusion hit hard: only 20 stocks explained most of the fund’s returns. He later distilled that realization into the brutal arithmetic of capitalism itself: over a rolling 10-year period, roughly 40 companies compound at 20% annually or better, crossing the 6x threshold. That’s about 1% of the market.

“Right. And that’s true, but at the time when I did this, no one had actually asked the simple question—in the history of the US equity market, which is to me, representative of capitalism—if there’s 4,000 average public stock, how many of them truly are great? And the philosophy we have today is predicated that over a rolling 10 year period, you have about 40 stocks that compound well with a 20% a year or go up a little bit over 6x. So about 1% of the stock market are the valedictorians, and that’s what we want to go do.“

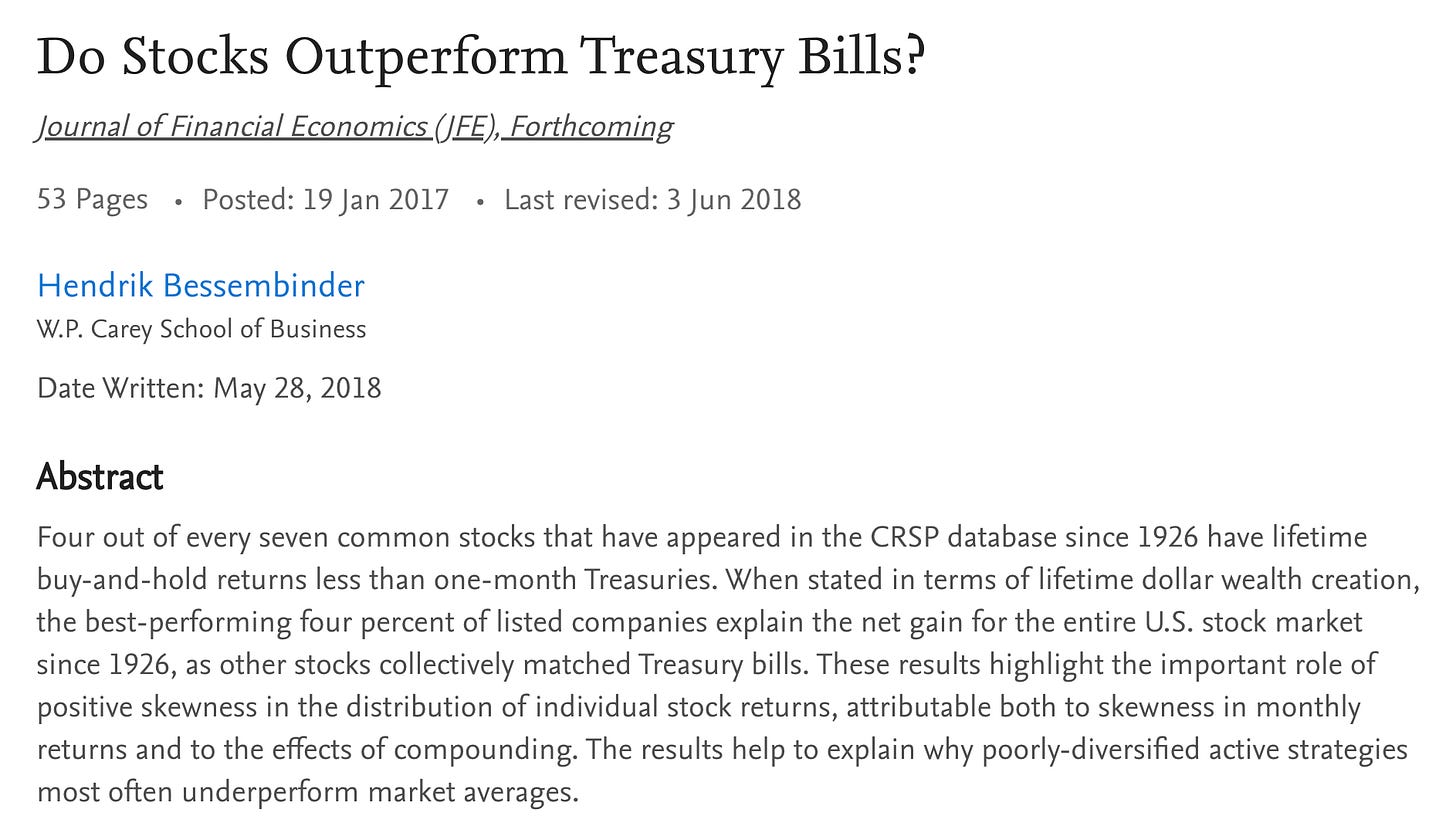

This insight reminded me of the now-famous study by Hendrik Bessembinder, often misquoted as evidence that equities fail over time. What the research really showed is something more precise and far more interesting: over very long horizons, the majority of individual stocks did not outperform 1-month T-Bills. Roughly 58% of U.S. stocks underperformed cash-like government bills over their lifetime. Yet – and this is the part that matters – a tiny fraction of extreme winners created essentially all of the net wealth generated by the equity market since 1926. Around 4% of stocks explained the entire cumulative gain, with the top 1% contributing a disproportionate share of total compounding.

But back to Henry Ellenbogen. His Walmart story sharpened the point further: Walmart went public with only 50 stores, tiny at the time, iterating under a founder who thought like an owner. “And obviously Walmart became Walmart.“ But it was sold early by the fund. The lesson Ellenbogen carried forward wasn’t just that Walmart worked. It was that trimming or exiting a true outlier can mathematically erase dozens of correct but smaller decisions. He summed it up with the kind of clarity that sticks: “The math was one bad decision, or maybe you had to make that decision every day because the public markets are open every day, […] [which] wiped out all these other good decisions.”

“And the math at the time was the retail fund—I think I was managing about $8 billion, which was the largest pool of small cap growth money in the country. And had the stake in Walmart not been sold, the stake in Walmart would've been greater than the sum total of everything that I was managing.“

Ellenbogen then talked about where to find these outliers. Most giants don’t start as giants. They become them. “About 80% of those companies start their compounding journey as small cap companies.”

In sum, if markets are this skewed, the real risk isn’t being wrong often. It’s being wrong on the few names that matter. Over-diversification into average businesses, trimming winners because of macro fears, or letting short-cycle incentives dictate your time horizon …

Insight #2: Act 2 Entrepreneurs – Pattern Recognition in People

Henry’s concept of “Act 2 teams” is arguably one of the most practical mental shortcuts shared during this episode. The idea is almost deceptively simple: founders who have built and scaled a company before start their next venture with sharper first principles, cleaner incentives, and scar tissue that actually helps them execute better and faster.

He illustrates it with Workday. The founders had already pioneered HR systems of record at PeopleSoft before Oracle’s takeover cut their original vision short. When cloud computing emerged, they attacked the same problem again – but this time with total clarity on the product, the edge cases, the go-to-market, and how to align the whole organization.

One quote that captures this advantage perfectly is: “and there's a huge advantage when you go do it again, you are essentially solving the same problem but with total clarity at the beginning.“ Another line that captures the idea is: “If you’ve been one before, you have a higher probability of being one again.”

Max Levchin, one of the co-founders of PayPal, is another recurring example for him. Ellenbogen had backed Max in his previous company, Slide, and later invested in Affirm. He calls out the specific attributes that matter most in these entrepreneurs:

communication clarity,

recruiting strength, and

resilience under pressure.

“But with all jokes aside, Max to me represents the best of an Act 2 entrepreneur. For those of you who don't have the benefit of knowing Max, first of all, he truly understands technology and he really understands how it can be used in very complex systems to solve problems. He can recruit exceptional people because he speaks their language. He's also a very good leader and people believe in him. He's also exceptionally resilient.“

For his fund, networking is a critical advantage here, too. Oftentimes, Ellenbogen and his team benefit from “compounding relationships” as he explains in this passage:

“If Durable does anywhere from five to 10 new investments a year, a lot of times it actually is with Act 2 entrepreneurs. And then if we're lucky, and this happens because of compounding relationships for having done this for 20 years, a lot of times it's with people that actually we were investors in their previous act. And I think that's also great, because they know us and we know them, we know each other's strengths and we know exactly how we can help each other.“

Henry Ellenbogen’s point is that betting on successful past founders gives you a probabilistic edge – the base rates go up essentially. A founder who has seen scale once and survived the stress that comes with building in public is a fundamentally different “asset class” than someone learning the ropes for the first time.

Insight #3: Physical World Moats Are Underrated

Ellenbogen lights up when he talks about the physical world. He loves moats rooted in physical infrastructure, the kind that require land, logistics, permits, capital, sequencing, and a culture that actually works once the assets are in place.

“So I deeply love these physical world moats that exist. And really, our portfolio has a lot of them in one way or the other.“

“You can’t spin those things up. These things that are super messy. You gotta acquire the land, you gotta put in the right place, you gotta build the right network, then you gotta go stand it up with the right CapEx and the right systems and then you have to have the right operating culture.”

Strictly speaking, he doesn’t just like companies with physical moats. He likes companies where physical-world assets and the “tech stack” work together, feeding off each other. The physical assets create the initial constraints and technology is the lever that bends those constraints into a widening gap, a widening moat. He said, “ideally what we go do is we go find those already advantaged companies and then they leverage this [note: a new innovative force] to go from good to great.”

“And often those are the best stocks when you go study the markets because you are already in a physical world business where the technology advantage transitions into a physical mode advantage or a distribution or scale advantage. That's one of the patterns that we've observed. We call that a good-to-great thesis internally.“

He also emphasizes location quality as part of unit economics, not just operations: “If you put your real estate in the wrong place, then your cost of transport’s more expensive.” In low-margin industries, small cost deltas compound into structural share shifts. And the companies that figured this out early – like Amazon acquiring Kiva and embedding robotics into their network – created advantages that translated from digital signals into physical dominance.

“I learned so many things from those meetings [with Jeff Bezos], but one of the things I learned is the very best businesses that leverage technology, leverage it in a way where they use it to lower costs and drive revenue that result in them gaining 30% or more incremental market share in their end market. And then they take that unit economic advantage and they reinvest it in something that is persistent, even if their competition were to wake up tomorrow and do the exact same thing with people just as good as they are.“

Understanding that technology can amplify physical distribution moats was a key insight for me. So if you’re building a mental database of businesses, don’t skip the “ugly” ones, the capital-heavy ones.

Insight #4: Digital Kaizen vs Physical Kaizen

Digital Kaizen and Physical Kaizen are often presented like opposing worlds, but Ellenbogen sees them as sequential, not rival, forces. When Patrick O’Shaughnessy floated the idea that “if [physical Kaizen and digital Kaizen] were to have a kid, it might be robotics And so I'm really curious how you approach the potential, with an unknown timeline, that we might get a second wave of […] Kaizen over the next 40 years,” Ellenbogen expanded on this idea.

“Kaizen (Japanese: 改善; “improvement”) is a Japanese concept in business studies which asserts that significant positive results may be achieved due the cumulative effect of many, often small (and even trivial), improvements to all aspects of a company’s operations. Kaizen is put into action by continuously improving every facet of a company’s production and requires the participation of all employees from the CEO to assembly line workers. Kaizen also applies to processes, such as purchasing and logistics, that cross organizational boundaries into the supply chain.“ - Wikipedia

His answer began with caution: “our views here are very early and probably deeply wrong,” but quickly turned into a mental model worth paying attention to.

He first describes how Kaizen reshaped physical industries for 40 years – driving working capital efficiency, factory throughput, and supply-chain radius advantages.

“Because Danaher, who he and his brother started and he’s chairman of, has been doing this for 40 years. It’s called DBS, and they basically brought Kaizen back to the US and they started […] by going into factories, putting processes up in whiteboards, studying how they could lean them out, leaning them out and coming back in a month later to make sure because change is hard, that the change is held. And then they basically built a whole business system which has basically not only helped build Danaher, but there’s over a dozen Fortune 500 CEOs in the United States who started their jobs at Danaher, including the guy who just has turned around GE.“

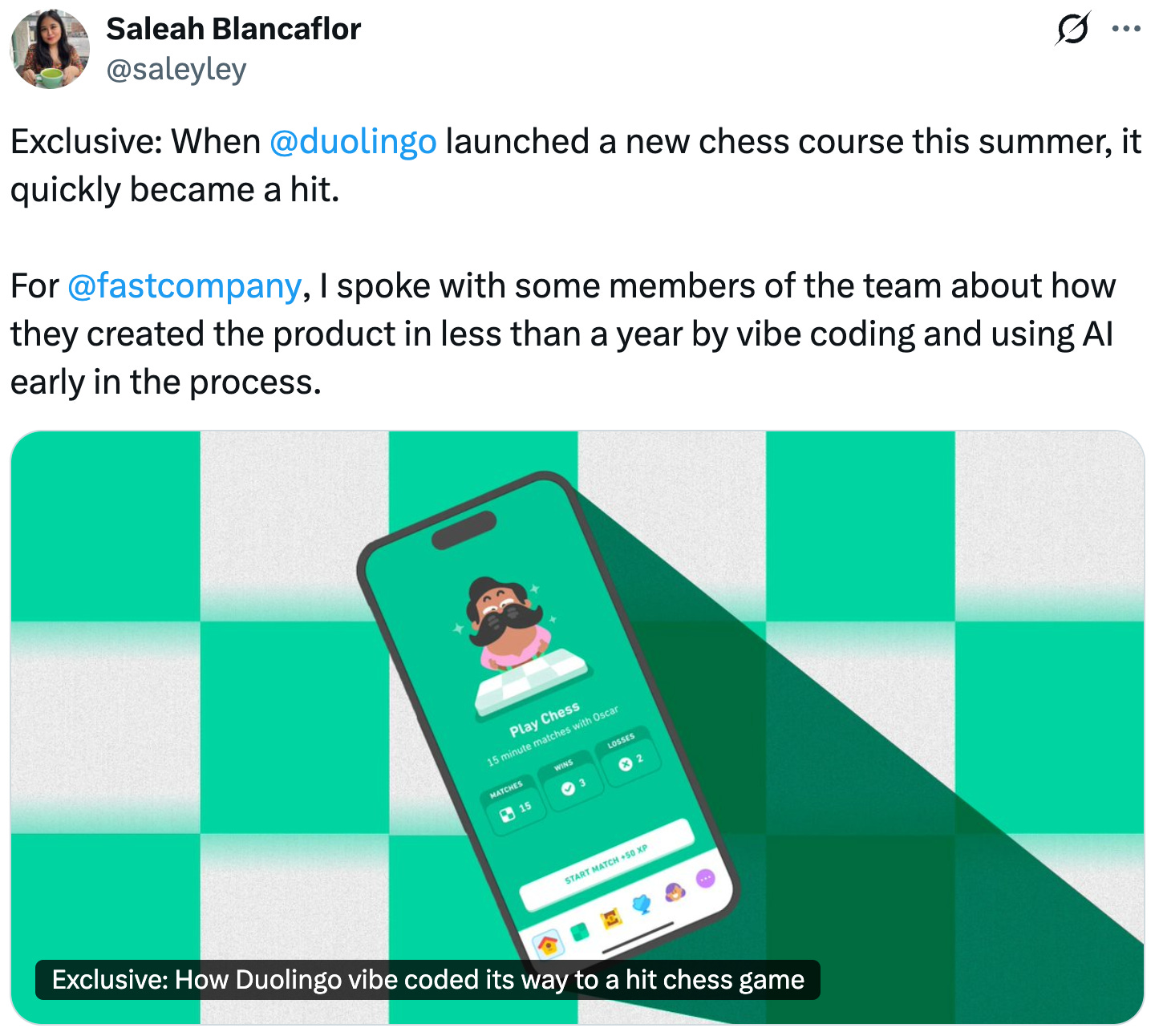

Now, AI represents a similar shift for knowledge work. Digital Kaizen can create extraordinary speed gains. He uses Duolingo’s CEO Luis von Ahn to illustrate that point: the ability to build a new product, Duolingo’s chess module – which, as Duolingo reported in its latest quarterly earnings, has become the “fastest-growing subject” in the company’s history –, in nine months with a fraction of the people it would have required before. Speed like that matters, but speed alone is not creating defensibility & durability.

“He's publicly said—he developed chess, which is doing incredibly well and my kids really love that product, I mean they're addicted to it—first it was two people for six months, and then he added another four people and he developed a product in nine months. That's the best product he's ever done.“

Historical base rates are useful, but not fully predictive here. The curve of improvement is steepening.

Physical Kaizen, as discussed in insight #3 to some extent, creates defensibility that can persist for decades. Amazon is his canonical example. The company didn’t just get better at software – it used software to push itself onto a deflationary logistics curve, then reinvested the advantage into physical infrastructure. In his words: “they took that 3-5% cost advantage of getting that box to you and their ability to put more than one item in the box, and they used that economic advantage to then go build fulfillment centers that are physical to reinvest into capital and infrastructure that allowed them to go down that 3% to 5% cost curve for 20 years.” Once the infrastructure was in place, only companies that still had real scale and trusted customer relationships – Walmart and Costco – could keep up when the curve became obvious to everyone else.

And we may be seeing similar dynamics playing out when it comes to integrating and leveraging robotics. Here’s what Ellenbogen had to say on this:

“… what we’re starting to get our heads around at Durable, which is in many areas robotics is at parity. Now there’s a lot of data that says it’s lower cost in certain cases. And the use cases are about to go up, and the cost on the existing use cases probably don’t go down at 3-5% at this point in the curve because of the scale brought in, the human capital brought in, the IP bought on. And the fact that you’re gonna be able to use these general purpose LLMs to power it, it probably goes down at more like 15 to 20%, but maybe it’s Moore’s law and it goes down even faster. Well then we wake up in five years and the people who put themselves on one cost curve, if they compete against the people who put themselves on the other cost curve, those could be power law businesses.

What we have thought really hard about is who’s gonna go benefit from this curve, where their competition—even if they woke up tomorrow, even if they put the same amount of money into this problem, even if they could hire the same quality of people, which is unlikely. Because they have not invested in the distribution infrastructure or the technological infrastructure to compete on this curve, at minimum, is probably two to three years behind and every day that they wait, they’re probably getting further behind.“

I kept thinking of InPost who may be a modern-day example of the concepts discussed here – they are investing aggressively in their physical-world moat/infrastructure (and have arguably reached a scale, no one will be able to catch up with anytime soon) while leveraging AI in their distribution centers, via their app, etc. (disclaimer: I own InPost shares; find my deep dive below).

The real insight for me is this: growth curves in companies aren’t only about how many customers they gain. Some curves describe how a business transforms itself – how it works, how fast it learns, how fast it lowers cost, how fast it scales output without scaling people. And AI represents an entirely new lever here. When a company absorbs AI or automation early, that may be the beginning of a new S-curve too – not in users, but in operational efficiency. By betting on companies that are nimble enough to adopt AI early, you’re underwriting a shift in how work gets done inside the business, which eventually decides who pulls away from the pack, and who gets left behind.

Insight #5: The Case for Public Markets

Ellenbogen does make a strong argument for companies becoming publicly traded. What resonated most is that he views the public markets as a mechanism that enforces feedback, expands scenarios management teams consider, and enables sharper internal alignment, decision-making, and capital allocation – especially during moments of transformation.

He acknowledges that staying private can be thoughtful for certain companies: “Maybe Elon is correct and SpaceX never has to go public. That’s really only happened in the last five years. Some people correctly pointed out this might be an incredible path for certain companies. And by the way, I think there’s some truth in it.”

But he also stresses that this is a new phenomenon, and that we’ll eventually know which model wins: “Here’s the good news about life. We’re gonna actually run an experiment. We’re gonna actually know the answer. I’m not saying that’s wrong.”

Still, his belief is clear: building durable compounders through public markets is a proven path, particularly when leadership knows how to use feedback constructively: “I believe the path to building a great company… through the public markets is proven.”

One of his most memorable points comes from the Netflix example. Reed Hastings’ shift from DVDs to streaming looked, as Ellenbogen puts it, “a little messy,” but the mess forced a conversation that made Netflix stronger. When Henry Ellenbogen called Reed on a Saturday to walk him through the financial implications of moving from a variable-cost model (renting DVDs from studios on usage) to a fixed-cost model (cutting large upfront checks for content and original programming), Reed initially pushed back: “Henry, what are you even talking about?” But crucially, he acknowledged the gap in his own underwriting, and invited the process battle instead of dodging it: “I have not thought about this as much as I should. Let’s talk tomorrow… You go through your scenario, we’ll go through ours and I can learn.”

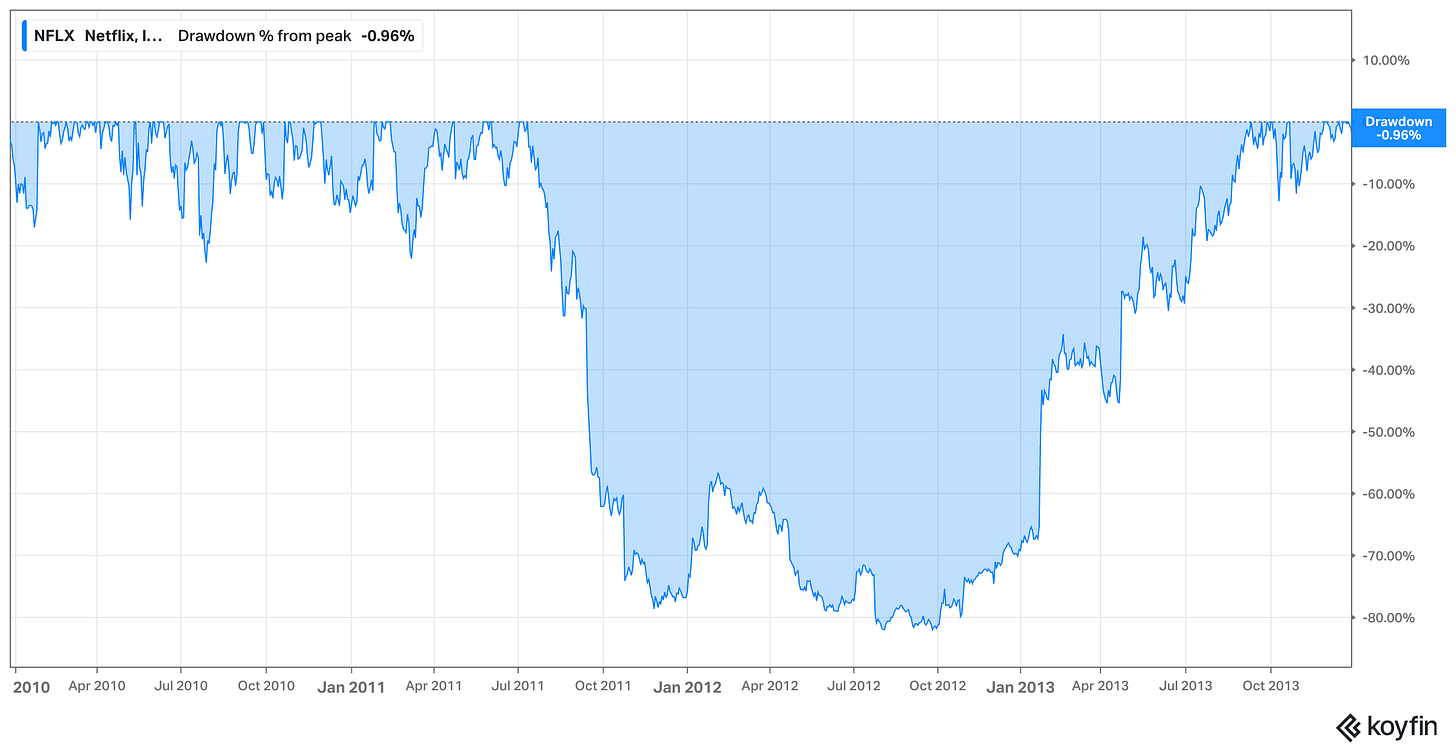

That exchange is the essence of what Ellenbogen values about public markets. The stock drop from $280 to $70 didn’t invalidate Netflix’s future – it validated the need to expand scenarios and tighten internal alignment while the stakes were still manageable. The public markets acted as a forcing function. Not to punish, but to clarify.

He also reframes the “finance function” in a way that many founders should hear earlier: “And what I always tell people about this is you should think about your CFO's function not as a policeman, but actually as someone who basically sells standards that force you to make sharp decisions [on capital].”

Ellenbogen also emphasizes that public companies don’t need to hit steady-state profitability overnight – but they must show direction. He recalled a conversation he had with Duolingo CEO Luis von Ahn: “You have a very unique humic capital culture, but if you’re gonna communicate to people this strength in the market, it doesn’t mean you need to get to your long-term margin targets at 30%, but you have to show progress towards it.“

“… you have to balance growth, profitability, and innovation. I talked earlier about if you're a growth company, you don't have to trade on a PE, but you have to show that path.“

The takeaway for me is simple. The public markets are not just a place to raise capital. They are a place that sends signals early, forces disciplined capital allocation, and aligns internal incentives.

Concluding Thoughts

What I maybe admire most about Henry Ellenbogen is that his thinking refuses to sit still. He rigorously studies markets, current trends, new innovative forces, the influence of incentives, and the patterns of “compounding companies” building their moats and legacy.

I love Invest Like The Best; not because every guest is aligned with my very own philosophy, but because some of the most interesting conversations make me revisit my own process, challenge my previous assumptions, and add new mental models and insights.

I picked five ideas from this conversation in this piece that felt most important to me, but there are more ideas in the episode; so I encourage you to listen to the entire episode next:

GREAT 1

Fantastic write-up on Ellenbogen's approach. The Walmart example really drives home how ruthless power law distibutions are in practice, one bad exit erasing dozens of correct calls is a humbling math. I've learned that conviction in outliers needs both patience and nerve, since trimming winers early feels safe in the moment but compounds into massive oppurtunity cost. Act 2 founders seems like a practical filter to improve base rates.