J.P. Morgan Beat the Tech Giants. Who’s Next?

From Momentum to Mean Reversion: The End of Big Tech's Era?

Note: The voiceover above is a custom-made, slightly adapted version of the blog post, edited for a smoother and more engaging listening experience. It’s one of the perks available to paid subscribers, as I’m always focused on adding as much value to my subscribers as possible. Enjoy!

When investors talk about bargains, they rarely think of megacaps. The prevailing wisdom is that inefficiencies show up on the fringes – in small caps, illiquid names, or obscure international plays.

But sometimes, bargains hide in plain sight. John Huber, the founder and portfolio manager at Saber Capital, recently pointed out that JPMorgan JPM 0.00%↑ – yes, the bank – has outperformed five of the “Magnificent 7” over the last five years. Specifically, it’s beaten Amazon, Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Meta. Only Broadcom (which has taken over Tesla) and Nvidia did better.

Even more interesting was how Huber broke down the reason:

That last sentence really stuck with me. Because it challenges one of the dominant investing narratives of the last decade: that only fast growth and massive scale matter.

That you could ignore valuation entirely as long as you had quality and a long enough runway. That owning anything outside the Mag 7 meant you were settling for second-tier performance.

But if JPMorgan – a bank, no less – can quietly outperform five of the most powerful companies on the planet, what else is possible? Are we seeing the start of a broader shift, where other businesses finally start to outpace the titans?

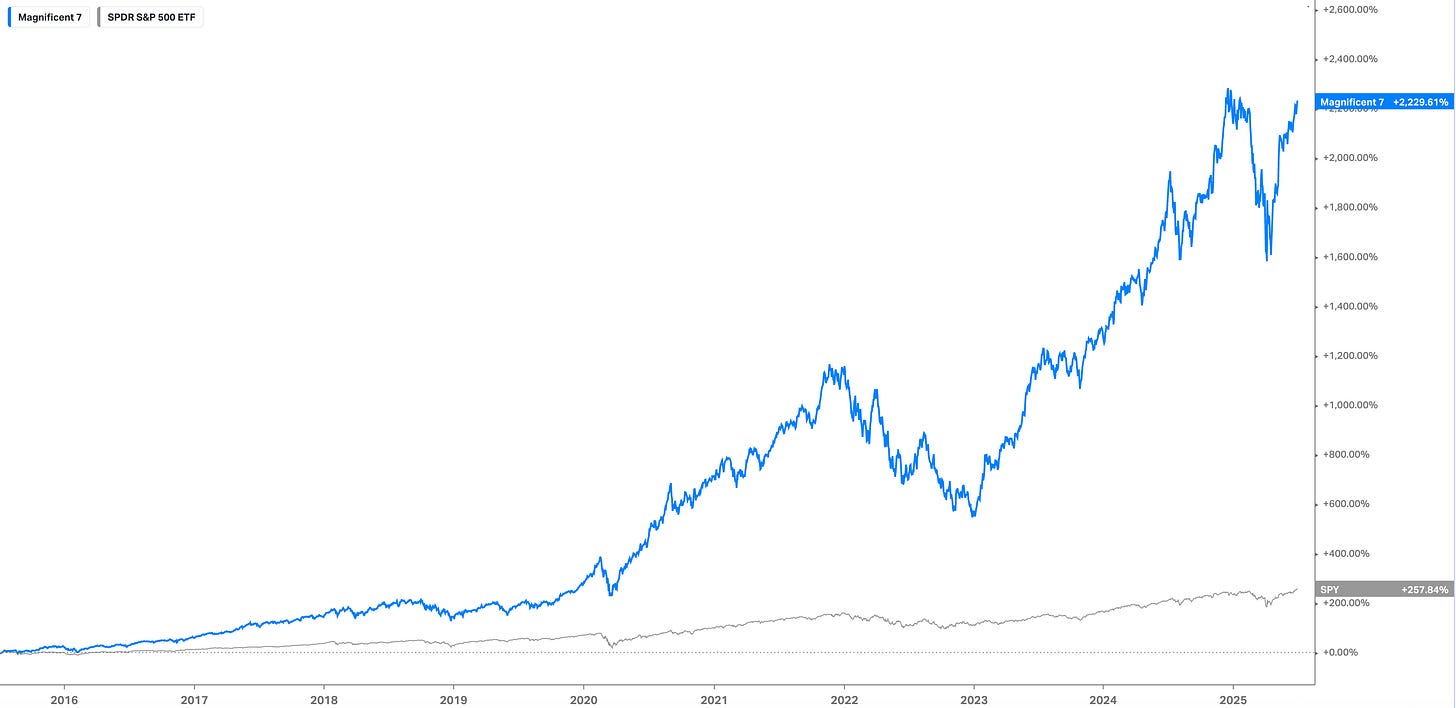

It wouldn’t have seemed plausible ten years ago. From the aftermath of the financial crisis through the peak of the post-COVID tech boom, the Mag 7 simply crushed everything. An equal-weight basket of those seven stocks (including Tesla and not Broadcom) delivered +2,230% over the past decade, compared to just +259% for the S&P 500.

For a long time, beating the market without holding these names felt close to impossible. Their dominance was so total, so persistent, that many investors gave up even trying to look elsewhere.

But I think we might finally be at a turning point.

The tides may not have fully turned yet – but the current is definitely shifting. Valuations are rich. Reinvestment dynamics have changed. Capital allocation decisions are murkier.

And meanwhile, there’s a long tail of quality companies trading at reasonable multiples, growing at a modest but steady clip, with far more room for multiple expansion.

So no – this isn’t a post claiming the Mag 7 are “doomed” or finished. They’re still great businesses. But it is a post about the opportunity cost of sticking with yesterday’s winners.

It’s about the possibility that a growing number of “normal” businesses, with solid fundamentals and less fanfare, might quietly start outperforming.

JPMorgan may just be the first crack in the façade.

Here’s what I’ll explore:

How JPMorgan outperformed 5 of the 7 Mag 7 stocks over the past five years – and what that says about valuation, modest growth, and capital returns

Why the Mag 7’s dominance may be fading and how the next cycle could reward different traits

What current valuation metrics (PE, EV/EBIT, PEG) reveal about risk and opportunity in today’s market

Why big tech’s capital allocation has fundamentally changed, and how massive CapEx and uncertain returns could affect long-term outcomes

What makes a reinvestment environment attractive vs. wicked, and why this matters more than ever when assessing future ROI (which in turn affects assigned multiples)

The significance of Meta’s M&A spree and hiring push – and what it reveals about the competitive pressure inside big tech

How many S&P 500 companies could realistically outperform the Mag 7 over the next five years – and what that means for active stock pickers

What kind of companies might lead the next cycle, and why thinking beyond the top 20–30 names in financial media coverage is critical

And finally, how I’m thinking about portfolio positioning in a world where tech no longer reigns supreme by default

Before we dive back in, a quick note…

Want to invest in the one edge that compounds forever? Join hundreds of investors sharpening their thinking, avoiding mistakes, and discovering quality before the crowd. Subscribe to CompoundWithRene and become a better investor over time.

Part 1 – The Valuation Perspective

Valuation Was Once a Joke – Now It Matters Again

For years, valuation was the punchline. Anyone bringing up PE ratios or discounted cash flow models in the age of ZIRP and “infinite” TAMs was often waved aside as being too “old school.”

The idea was that if you were focused on cash flow or balance sheet strength, you just didn’t “get it.”

Multiples could be stretched to the sky if the company was growing fast enough – and if it wasn’t, well, maybe you shouldn’t own it in the first place.

But that era is fading. Interest rates are higher (for longer). Liquidity is scarcer. And the tolerance for wildly optimistic forward projections is dropping. Suddenly, valuation is not just relevant again – it's central.

The Magnificent 7 are still dominant businesses, but on most traditional valuation metrics, they no longer look remotely cheap. In fact, many (not all) of them now trade well above the S&P 500’s average multiple – a far cry from the early 2010s when they were the rare combination of growth and value.

A Simple PE Ratio Comparison Tells a Story

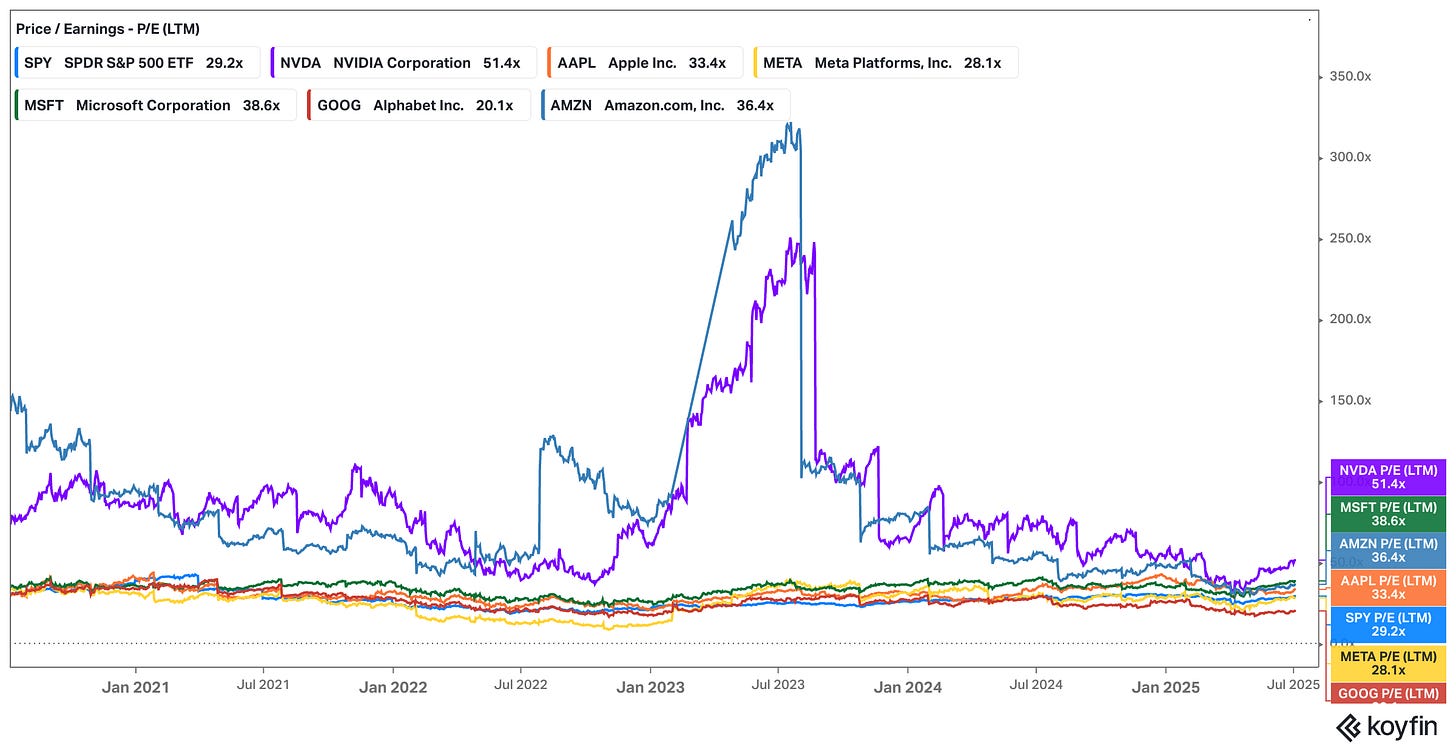

Let’s start with the basics. On a trailing PE basis, 5 out of the 7 Mag 7 names are currently trading above the S&P 500’s average. If you strip out Tesla – which sits in a category of its own with a multiple north of 180 – the valuation gap is still significant.

Companies like Nvidia and Microsoft, trading at multiples of 51x and 38x respectively, while still cash flow machines, are trading at very high near-term earnings multiples. Amazon and Apple? Their trailing valuations look optically rather rich too.

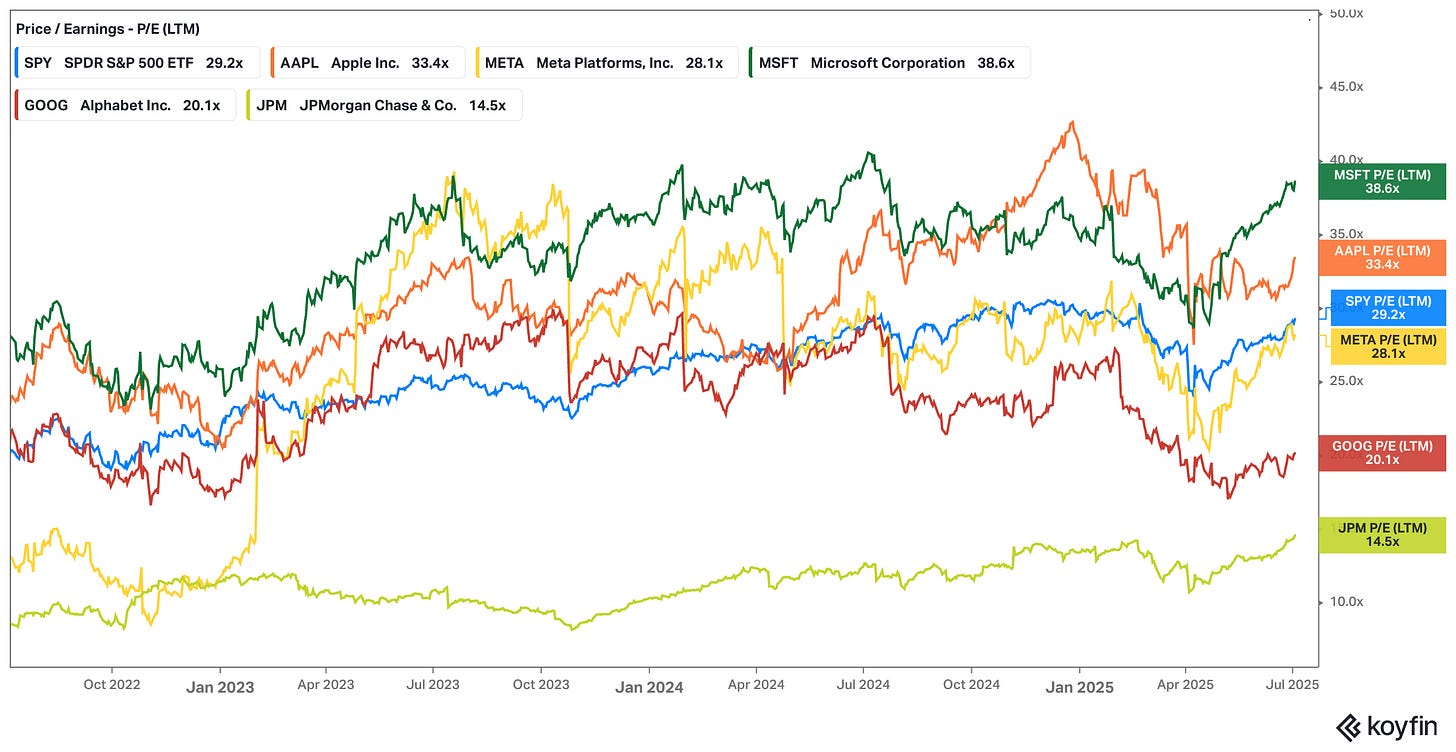

In contrast, JPMorgan’s PE ratio in July 2022 was just 8.3x. That’s not just cheap. That’s downright neglected.

Since then, JPMorgan’s multiple has expanded to 14.5x, which is still more than 50% below the average Mag 7 valuation. That multiple re-rating alone has added 20.44% in compounded returns – without even factoring in dividends or underlying earnings growth.

This is what happens when a modestly growing company gets re-rated from "cheap bank stock" to "decent quality equity."

The EV/EBIT Lens: Even More Lopsided

Valuation stories can look a bit different depending on which metric you use – and EV/EBIT adds another layer of nuance. On a next-twelve-month (NTM) EV/EBIT basis, 6 of the 7 Mag 7 companies trade at a higher multiple than the S&P 500. And again, the chart below is excluding Tesla.

This metric is particularly relevant because it strips out the effects of capital structure and shows how much investors are paying for operating earnings. In environments where capital costs have risen – like today – it becomes even more meaningful. High EV/EBIT multiples now demand much more from a company than they did three or four years ago. Every basis point of yield, every dollar of retained earnings, carries more weight. The hurdle to justify these valuations has risen sharply. And the Mag 7? Well, they’re not cheap by any means.

And it raises the question: What are investors really paying for?

If the answer is “AI growth” or “platform scale,” … well, these narratives eventually need to be paired with actual return on investment. And that's where things start to get tricky for most of the “AI plays.”

If you’re betting on Meta and Alphabet, you might be interested in a more bullish perspective:

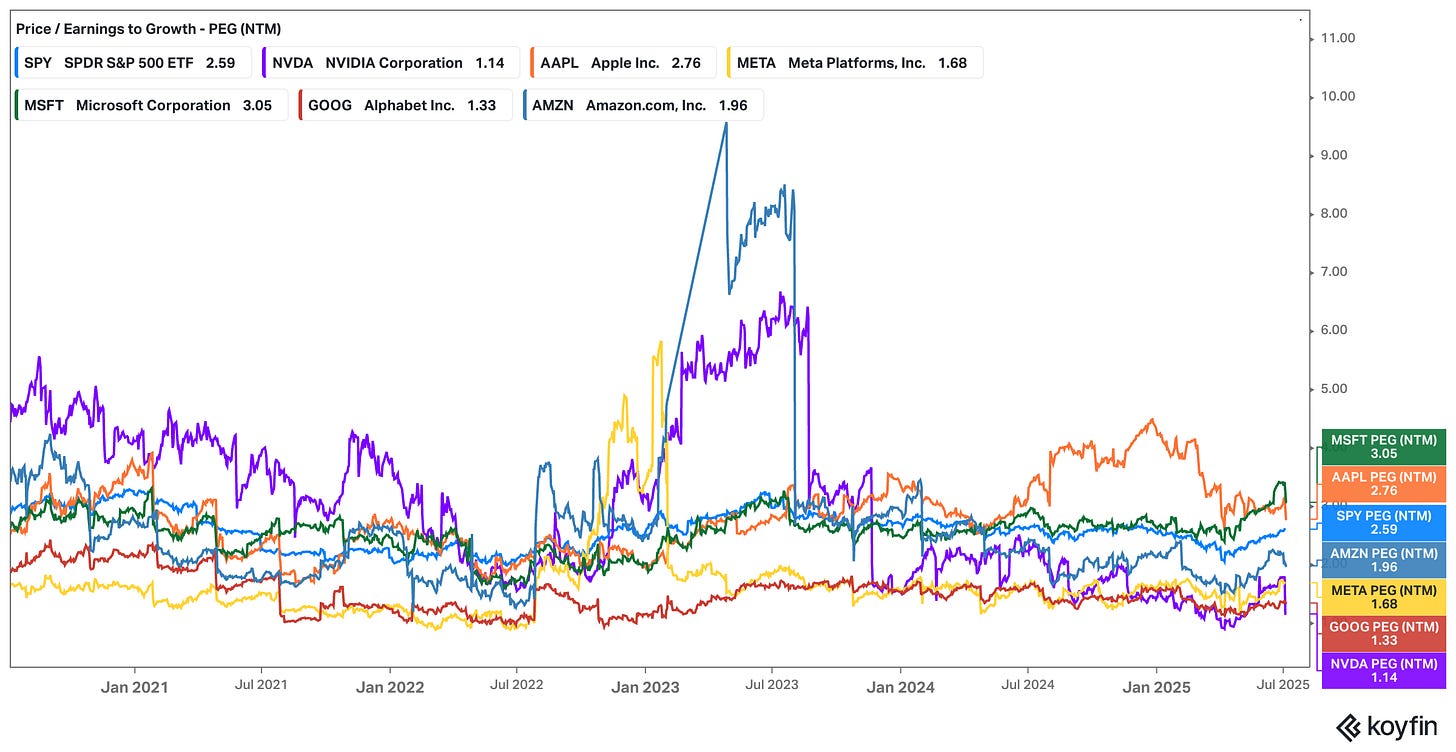

PEG Ratios: The One Metric That Offers a Counterpoint

To be fair, not every metric screams “overvalued.” The PEG ratio – price-to-earnings relative to growth – softens the picture a bit. On a PEG basis, 4 out of the 7 Mag 7 stocks actually trade at more reasonable levels, especially when next year’s growth is factored in.

But the PEG ratio comes with its own trap: it assumes the growth is real, repeatable, and durable. And in some cases, that assumption is doing an awful lot of heavy lifting. For instance, if Nvidia’s future earnings stumble even slightly, or margins compress, the entire justification for today’s multiple begins to crack.

When expectations are this high, as they are for Nvidia NVDA 0.00%↑ and Microsoft, there's no room for missteps – and that’s often when performance starts to underwhelm.

JPMorgan as a Case Study in Multiple Expansion

Let’s return to JPMorgan for a moment. In July 2022, as mentioned, it was trading at 8.3x PE. Now, it trades at 14.5x. That’s a near doubling of its valuation multiple in just two years, and the stock has rallied hard as a result. Importantly, this happened without extraordinary revenue growth or a massive buyback announcement. Instead, it was driven by three modest but compounding factors: low starting valuation, modest but consistent growth, and disciplined capital return.

This is what makes the JPM case so compelling. It didn’t require some speculative leap of faith. It just required recognizing a decent business that had been left behind. And there are more of those out there than most investors realize.

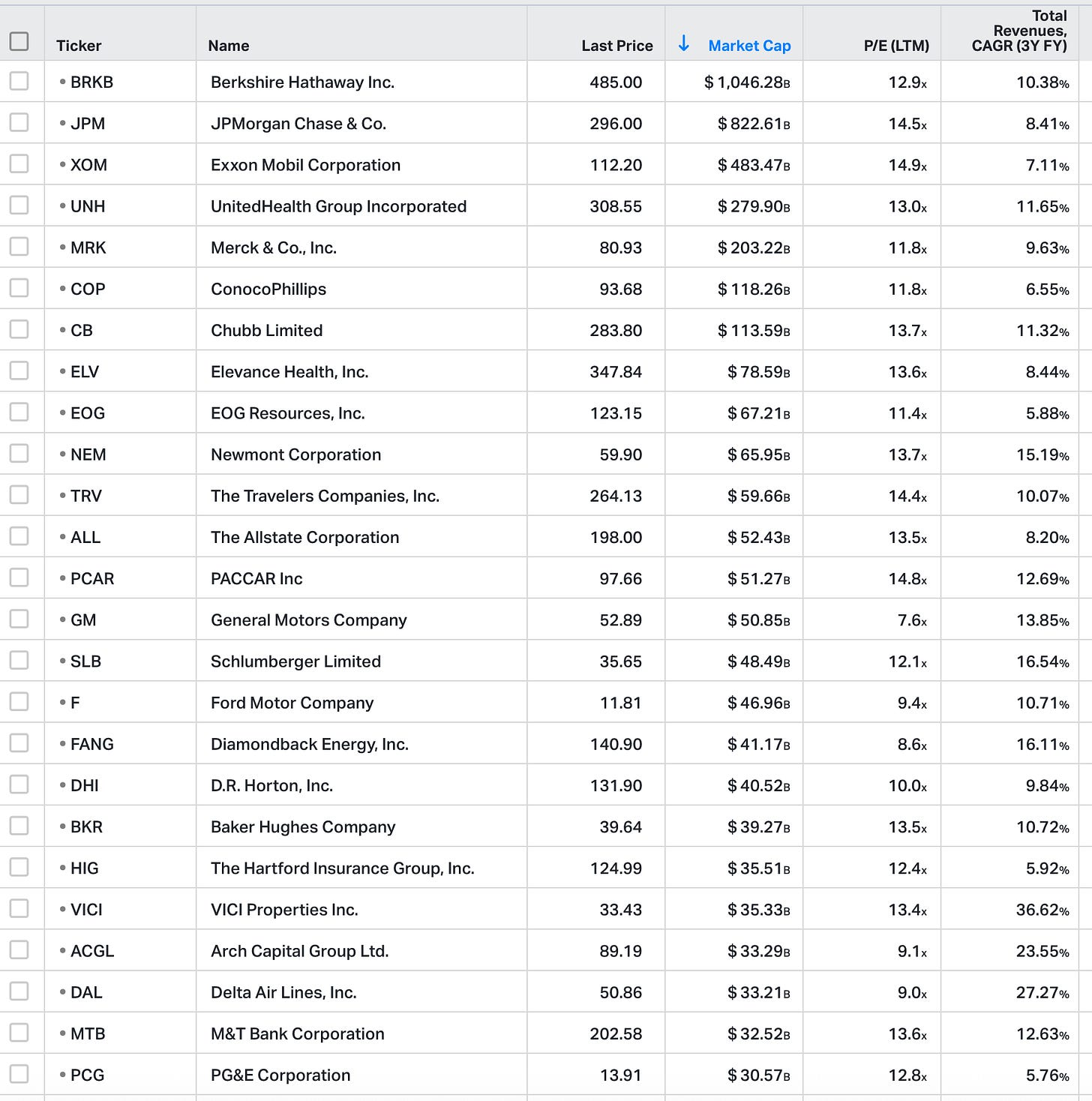

In fact, when I ran a screen on the S&P 500 for companies trading at a LTM PE below 15x, with topline growth above 5% CAGR over the past three years, I got 40 names. That’s not a tiny niche.

Here’s the list. If you’re only allowed to invest in the US, start hunting!

That’s a real opportunity set. And interestingly, JPMorgan is still on that list, even after the run-up.

Valuation Is Just the Start – But It’s a Powerful Filter

Of course, not all of those 40 names will outperform. Valuation screens are blunt instruments. They don’t tell you if a company is operating in a declining industry, has structural headwinds, lacks reinvestment opportunities, or is run by a mediocre management team. That’s where qualitative research comes in.

But as a starting point, these screens remind us that there’s life outside the Mag 7.

And more importantly, outperformance doesn’t require perfection. It just requires not overpaying and giving yourself a margin of safety – something the market hasn’t prioritized in years.

The trap is thinking that because the Mag 7 have been exceptional performers, they must always remain so (recency alert bing bing bing!).

But history shows us that starting valuation is one of the most powerful predictors of future returns – especially when capital costs rise, the business model gets heavier, and new growth vectors become less certain (more on this below).

The thesis of this post is that the age of ignoring valuation is over. If anything, it was the exception all along.

Part 2 – The Capital Allocation Perspective

The Asset-Light Narrative Is Dead

One of the great myths of the past decade was that big tech was inherently capital-light. That you could scale up users, revenue, and margins without breaking a sweat – or the bank. Google didn’t need factories. Meta didn’t need inventory. Amazon was maybe the odd one out. But most of the Big Tech names were considered capital-light compounders. Machines that turned every dollar into three or four more, with minimal friction.

But that story’s over.

Today, capital allocation inside the Mag 7 looks very different. The top tech names are pouring tens of billions into physical infrastructure – mostly into data centers, chips, and AI-driven compute capacity. In fact, the tech megacaps plan to spend more than $300 billion in 2025 as AI race intensifies

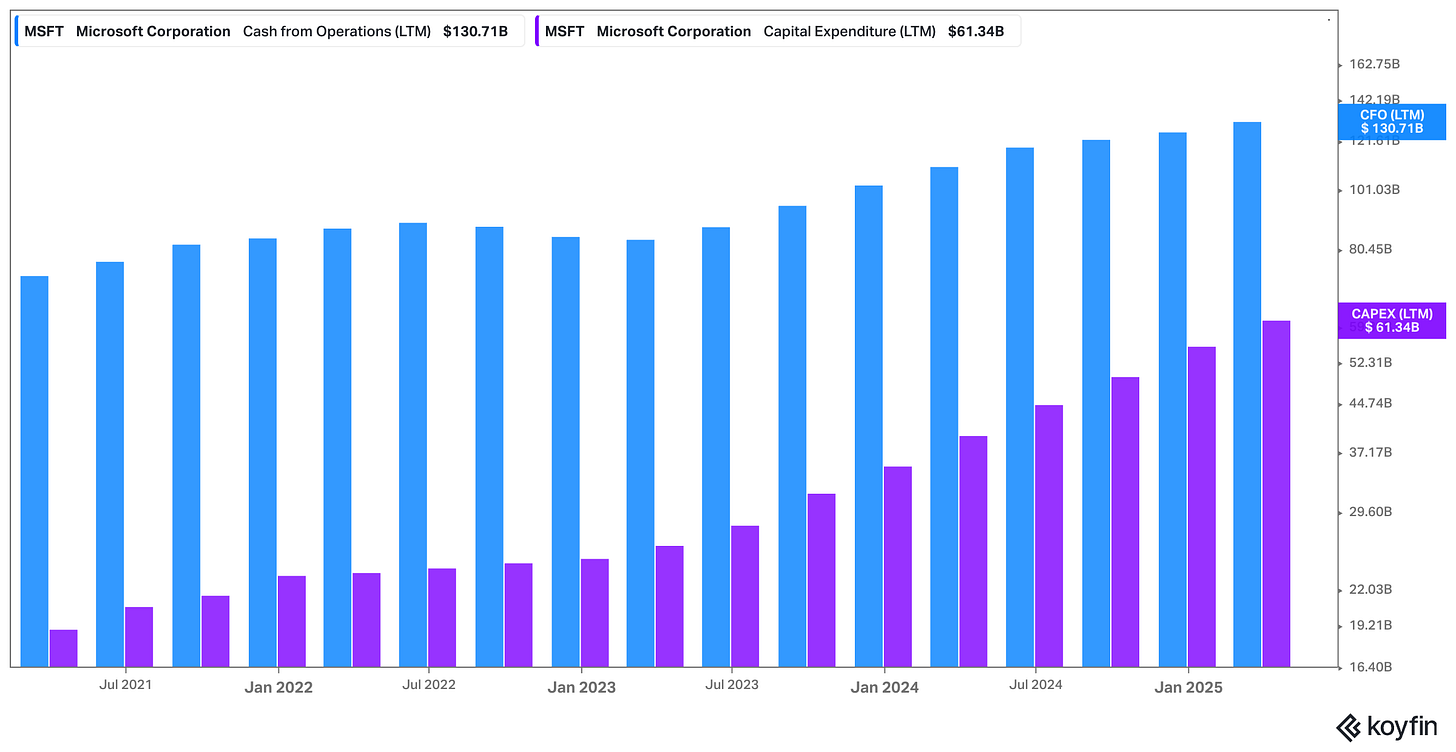

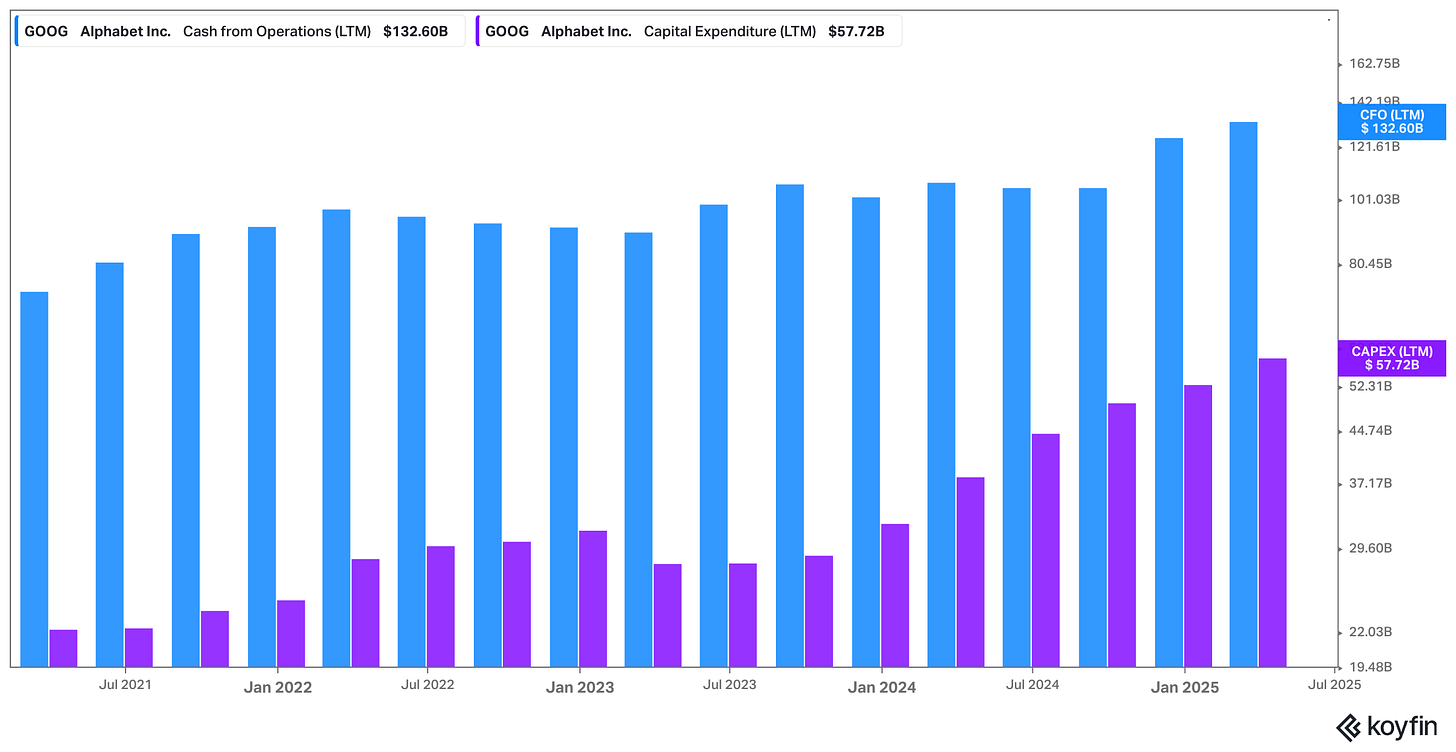

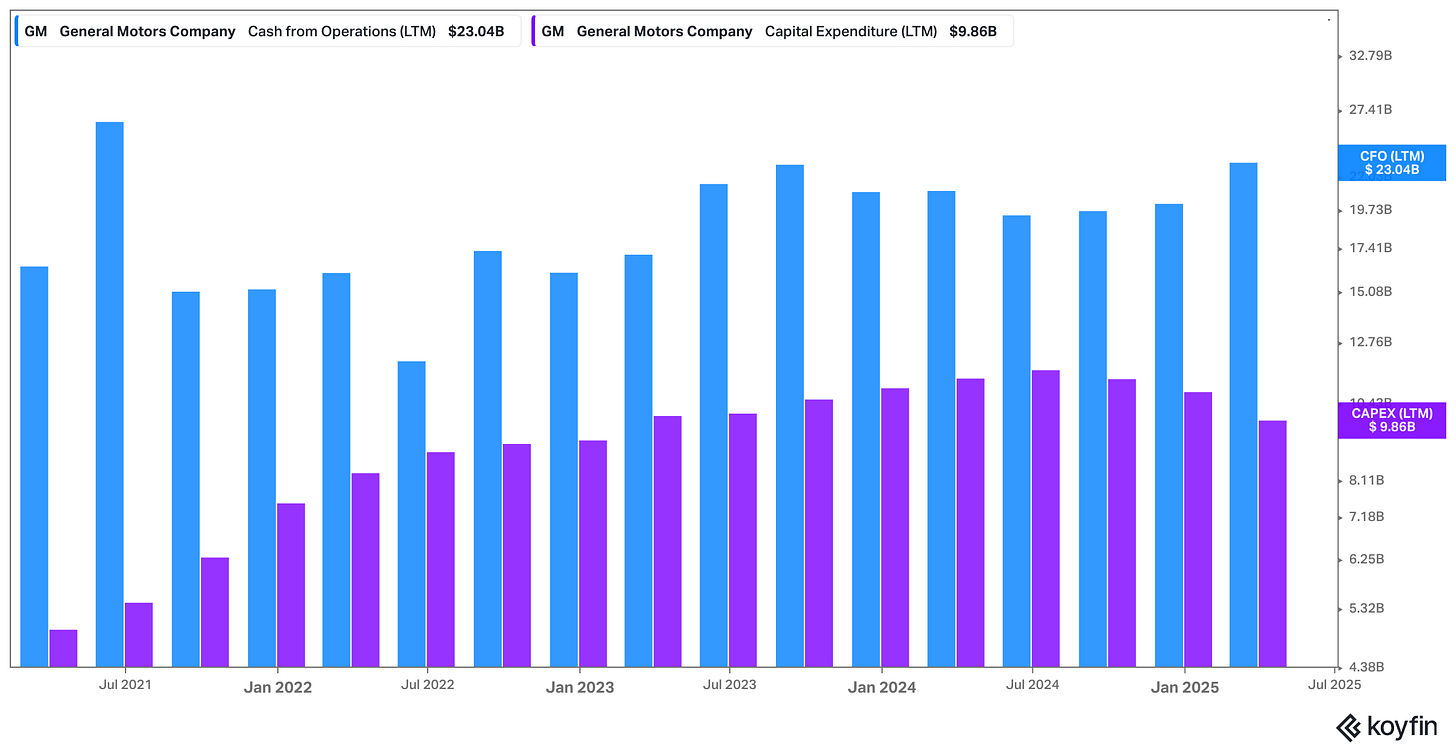

The capex-to-cash-flow ratios are staggering. These companies are no longer asset-light software companies. They’re infrastructure businesses. And they’re investing like it. Here are some numbers:

Microsoft MSFT 0.00%↑ is plowing 46% of its operating cash flow into CapEx

Meta META 0.00%↑ is close behind at 45%

Alphabet GOOG 0.00%↑ comes in at 43%

Amazon AMZN 0.00%↑ tops them all with a staggering 82% reinvestment rate

To put that into context: these ratios are higher than General Motors (42.6%) – a company we used to think of as the definition of capital intensity.

The idea that these firms are just floating above the physical world is no longer true. And that shift has real implications for how we think about return on invested capital, reinvestment risk, and valuation support.

Where’s the ROI?

The logical next question is: What are they spending on, and what kind of returns will they get?

The bulk of the money is going toward AI infrastructure. That includes everything from custom chips to massive data centers and high-performance compute clusters. The hope is that these investments will pay off through higher productivity, new products, and competitive advantage in the AI arms race.

But here's the uncomfortable part: The ROI is completely opaque. No one knows what the return on these investments will be. We don’t have good historical precedents. We don’t have long-tailed user behavior to analyze. And we definitely don’t have visibility into how much of the AI productivity gains will accrue to the platform layer vs. the application or consumer layer.

In other words, these companies are deploying capital at a staggering rate – and we’re flying blind when it comes to long-term payback.

That’s not to say the investments are dumb. Some may pay off handsomely. But the environment they’re operating in isn’t exactly conducive to high returns.

The Characteristics of a Wicked Reinvestment Environment

Let’s take a step back and ask: What makes for a great reinvestment environment? I’d argue the best ones share a few traits:

Low or no competition

High predictability

A history of similar investments paying off

Simple, modular rollout strategies (think restaurants or software)

Clear, unit-level economics

Optionality without excessive upfront capital

Now let’s contrast that with the current AI infrastructure buildout:

The environment is highly competitive – every big player is spending aggressively

There’s massive uncertainty about monetization models

Competitors are well-funded and moving fast

The ROI on investment is murky at best

Many of the use cases are still experimental, and long-term demand is speculative

This isn’t a “roll out another store and earn 30% ROI” scenario. This is a wager on an uncertain frontier, one where the prize is unclear and the cost of staying in the game is escalating.

That’s a tough environment to earn alpha in. Especially when you’re spending at industrial scale.

The Return of M&A – and a Hint of Desperation?

There’s another twist here: acquisitions are back on the table, and they’re coming in hot. Meta has been particularly aggressive, trying to scoop up AI startups like Scale AI and targeting firms like Perplexity and Safe Superintelligence (SSI), the closely guarded startup co-founded by former OpenAI chief scientist Ilya Sutskever.

They’re also making wild recruitment offers to key AI talent – reportedly $100M+ “exploding offers” – job offers with very short deadlines for acceptance, often within 24 to 72 hours, after which the offer is rescinded – for OpenAI executives.

Now, with the Trump administration expected to take a more business-friendly stance and a FTC leadership, M&A may face fewer regulatory hurdles. But even so, the strategic rationale behind some of these moves feels less like a chess game and more like a scramble not to be left behind.

That’s a big psychological shift. These companies once set the pace. Now they’re reacting.

Of course, they have the cash to do it. And in theory, the platform advantage should still count for something. But when companies with $100B+ war chests start behaving like desperate startups trying to hoard scarce talent, it tells you something about the perceived threat level.

Why This All Matters for Investors

This shift in capital allocation is more than just a line on a cash flow statement. It fundamentally changes the investment thesis for these companies.

In the old days, you could underwrite big tech as capital-efficient cash machines. Minimal reinvestment required. Margins stable. Growth predictable. That’s what justified their premium valuations.

Now, they’re making massive bets into uncertain areas with unclear time horizons and opaque payoffs. And the market hasn’t fully adjusted its expectations.

That’s where the opportunity lies – not necessarily by shorting the Mag 7 (I’m not), but by recognizing how high the bar is for these names to keep compounding at historical rates. If those bets don’t work out perfectly – if ROI comes in below expectations, if competitive dynamics shift, if regulation catches up – the downside isn’t trivial.

Meanwhile, there are companies out there generating solid returns on capital, with far more predictable futures, trading at half the multiple.

The capital allocation game has changed. And investors who continue to treat the Mag 7 as infallible compounding machines are ignoring that shift at their peril.

Part 3 – Scenario Analysis

The best part is just ahead — unlock the full post to continue.

Investing is the one domain where better thinking compounds. If this intro gave you new insights, the full piece goes even deeper. A paid subscription is an investment in your decision-making process – and your returns.