Investing in China When the Rules Are Changing: Opportunity, Illusion, and Tail Risk

Cheap multiples, Taiwan risk, and a nuanced look at ADRs

For the last few days, I’ve found myself thinking about a Chinese company that I’m seriously considering adding to. On a purely bottom-up level, the stock looks extremely cheap. Cheap in the old-fashioned sense of price versus underlying business quality and growth.

And yet, the more time I spent toying with the idea, the less time I spent thinking about the company itself. Instead, my thoughts drifted somewhere else entirely – to geopolitics, to the shifting architecture of global power, and to a question that feels uncomfortable but increasingly unavoidable: what does it really mean to own Chinese equities in a world where the rules are no longer as stable as we liked to assume just 1-2 years ago?

I don’t usually spend much time thinking about an equity thesis this way. Most of the time, valuation, unit economics, competitive positioning, management integrity, balance sheet strength, optionality in adjacent markets, long-term growth trajectories, etc., dominate my thinking.

But this time … something was different. The stock itself is almost the easy part – from a fundamental perspective, it’s basically a no-brainer.

The harder part is figuring out how to think about tail risks that don’t show up in cash flow models or consensus estimates.

Specifically, I kept circling back to Taiwan. Not because I suddenly turned into a geopolitical strategist, but because the current global environment feels qualitatively different from what we’ve been used to over the last few years and decades. The Trump administration’s increasingly transactional approach to alliances, the attempt to reshape spheres of influence in places like Venezuela, the Greenland episode, the broader erosion of multilateralism – all of this creates an atmosphere in which great powers may start believing that the window for decisive moves is opening rather than closing.

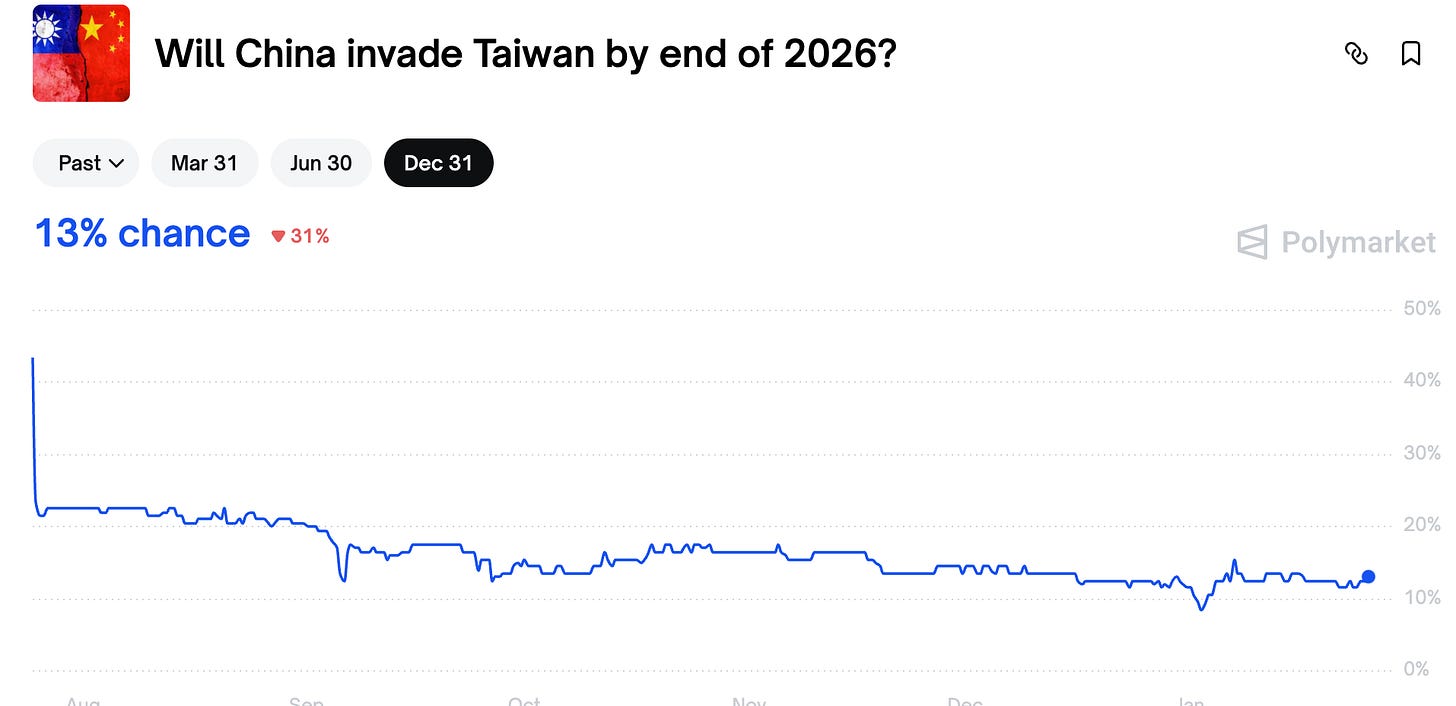

To be clear, I don’t think a Taiwan invasion is the base case. But I do think the probability distribution has shifted. And when you invest in Chinese stocks, even a small shift in tail risk matters.

There is a temptation to dismiss these concerns as noise. Markets, after all, have a long history of climbing walls of worry. Chinese equities themselves, in recent years at least, seem to tell a story that is far less dramatic than the headlines suggest. If you look at the CSI index over the last year, the trajectory is quietly constructive.

After a weak phase earlier in 2025, the index recovered steadily, ending the period solidly positive.

Stretch the horizon to three years and the picture becomes more nuanced: a prolonged drawdown, a sharp inflection, and then a recovery that feels less like euphoria – after all, a 10-15% 3-year performance is not goin to impress anyone on Wall Street – and more like a slow rebuilding of confidence.

The KWEB ETF paints a similar picture – not a runaway bull market, but a market that reflects a much more favorable sentiment toward China over the last twelve months, but longer term has been doing pretty terribly even after the recent runup (down 58% over the last five years).

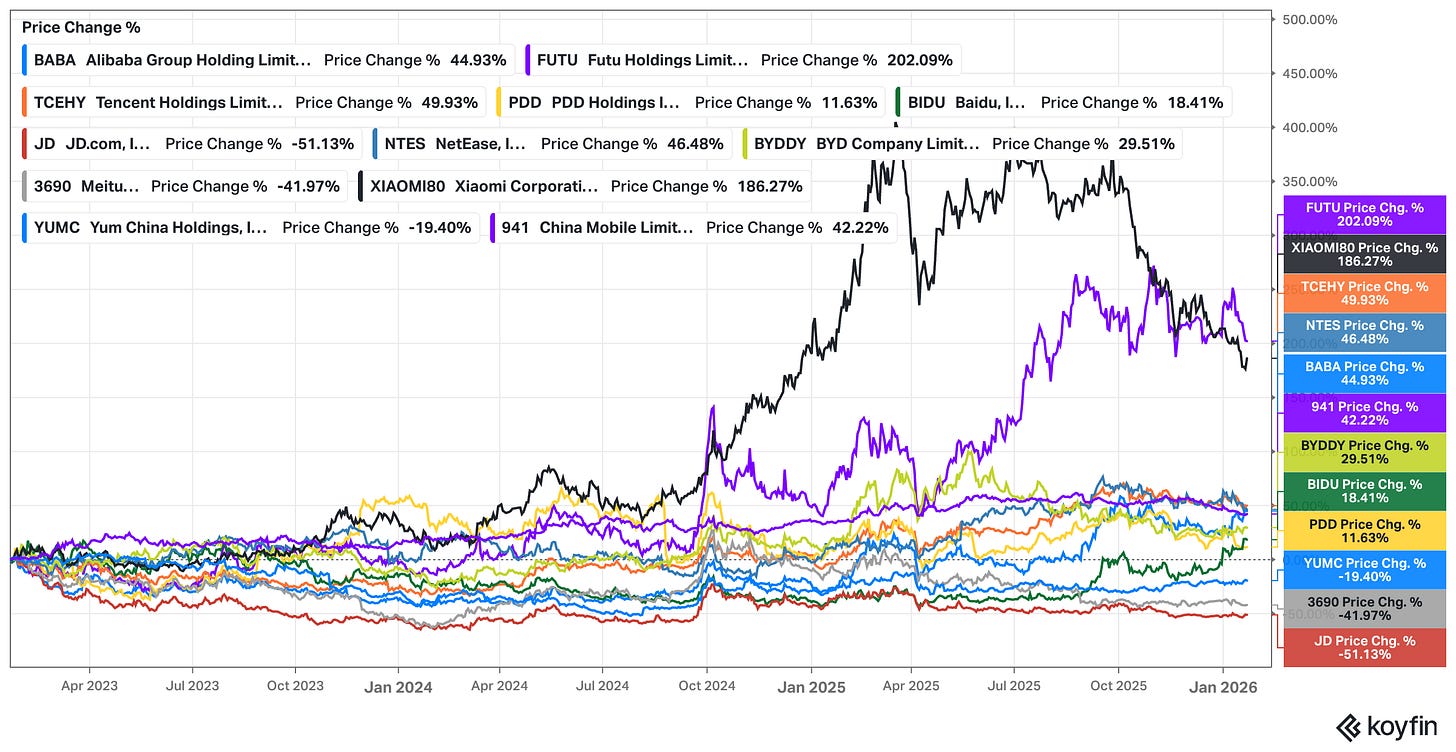

Then there are individual stocks. When you overlay the performance of major Chinese names over the past few years, the dispersion is striking. Some stocks have compounded spectacularly, others have stagnated or declined. This is not a market moving in lockstep with a single macro narrative. It is a market where company-specific fundamentals still matter, even if they are constantly filtered through a geopolitical lens.

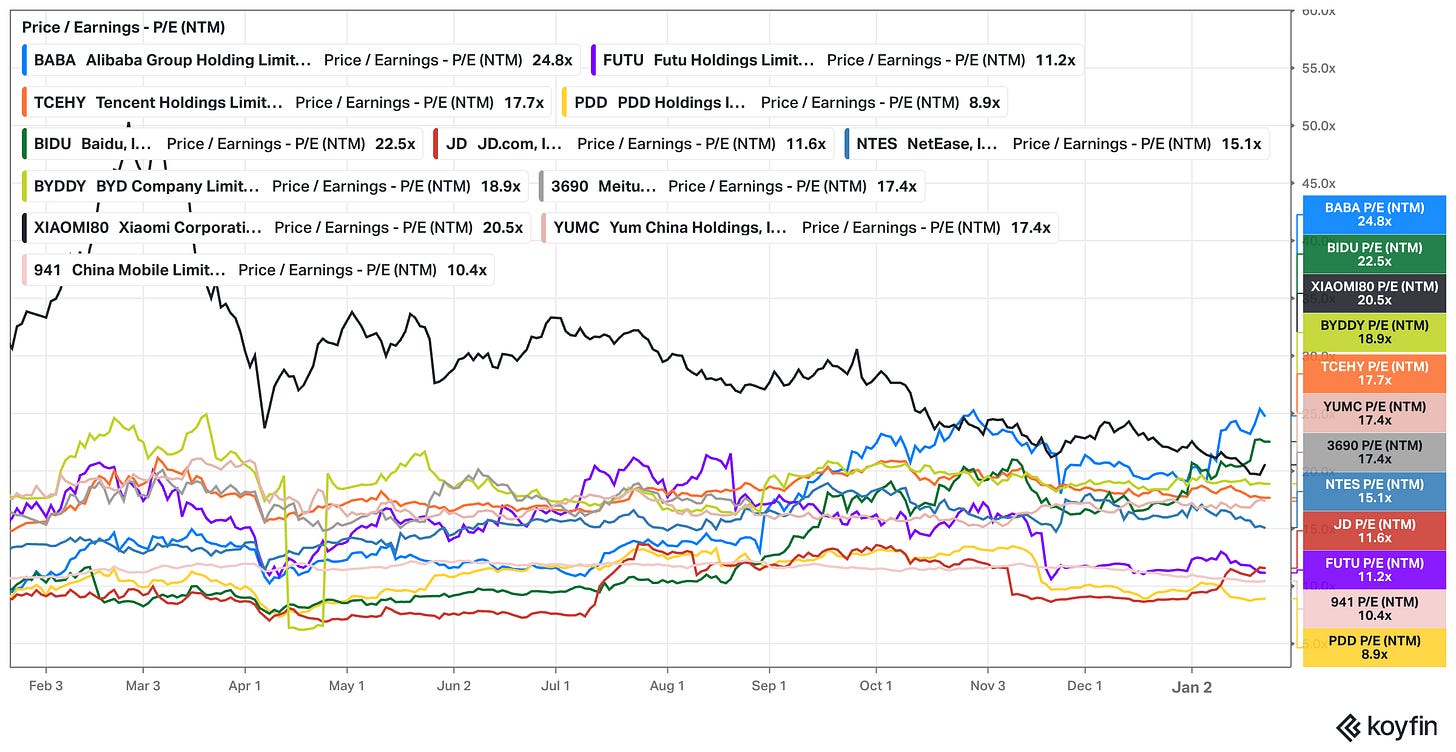

Valuations reinforce that impression. Forward P/E ratios across leading Chinese companies span a wide range, but many sit at levels that would look conservative in almost any other major market – especially by US standards.

At this point, I kept thinking about a speech that Canada’s prime minister Mark Carney delivered at this year’s Davos meeting. It struck me because it captured, in unusually vivid language, the psychological dimension of the current world order. Before getting to the investment implications, it’s worth sitting with his metaphor for a moment, because it frames the entire problem.

Carney described a world in which the comforting fiction of stable rules is slowly dissolving, replaced by a harsher reality in which power politics is no longer constrained in the way we assumed it was. He reached back to Václav Havel and the image of a greengrocer who displays a sign he does not believe in, simply to avoid trouble. The system persists not because it is true, but because everyone behaves as if it were true. And the moment one person removes the sign, the illusion begins to crack. Carney put it like this:

“Today I will talk about a rupture in the world order, the end of a pleasant fiction and the beginning of a harsh reality, where geopolitics, where the large, main power, geopolitics, is submitted to no limits, no constraints. [...] It seems that every day we’re reminded that we live in an era of great power rivalry, that the rules based order is fading, that the strong can do what they can, and the weak must suffer what they must. And this aphorism of Thucydides is presented as inevitable, as the natural logic of international relations reasserting itself. And faced with this logic, there is a strong tendency for countries to go along to get along, to accommodate, to avoid trouble, to hope that compliance will buy safety.

Well, it won’t.

So, what are our options? In 1978, the Czech dissident Václav Havel, later president, wrote an essay called The Power of the Powerless, and in it, he asked a simple question: how did the communist system sustain itself? And his answer began with a greengrocer. Every morning, this shopkeeper places a sign in his window: ‘Workers of the world unite’. He doesn’t believe it, no-one does, but he places a sign anyway to avoid trouble, to signal compliance, to get along. And because every shopkeeper on every street does the same, the system persist – not through violence alone, but through the participation of ordinary people in rituals they privately know to be false. Havel called this ‘living within a lie’. The system’s power comes not from its truth, but from everyone’s willingness to perform as if it were true, and its fragility comes from the same source. When even one person stops performing, when the greengrocer removes his sign, the illusion begins to crack. Friends, it is time for companies and countries to take their signs down.”

When I read this, I couldn’t help but translate it into investment language. For decades, global markets have operated under a shared assumption: that economic interdependence would act as a stabilizing force, that extreme geopolitical ruptures were unlikely because they were too costly, and that the plumbing of global finance would continue to function even in periods of political tension.

Times have changed, though. Today, cracks in the above assumptions are becoming harder to ignore. Here’s how German chancellor Merz put it:

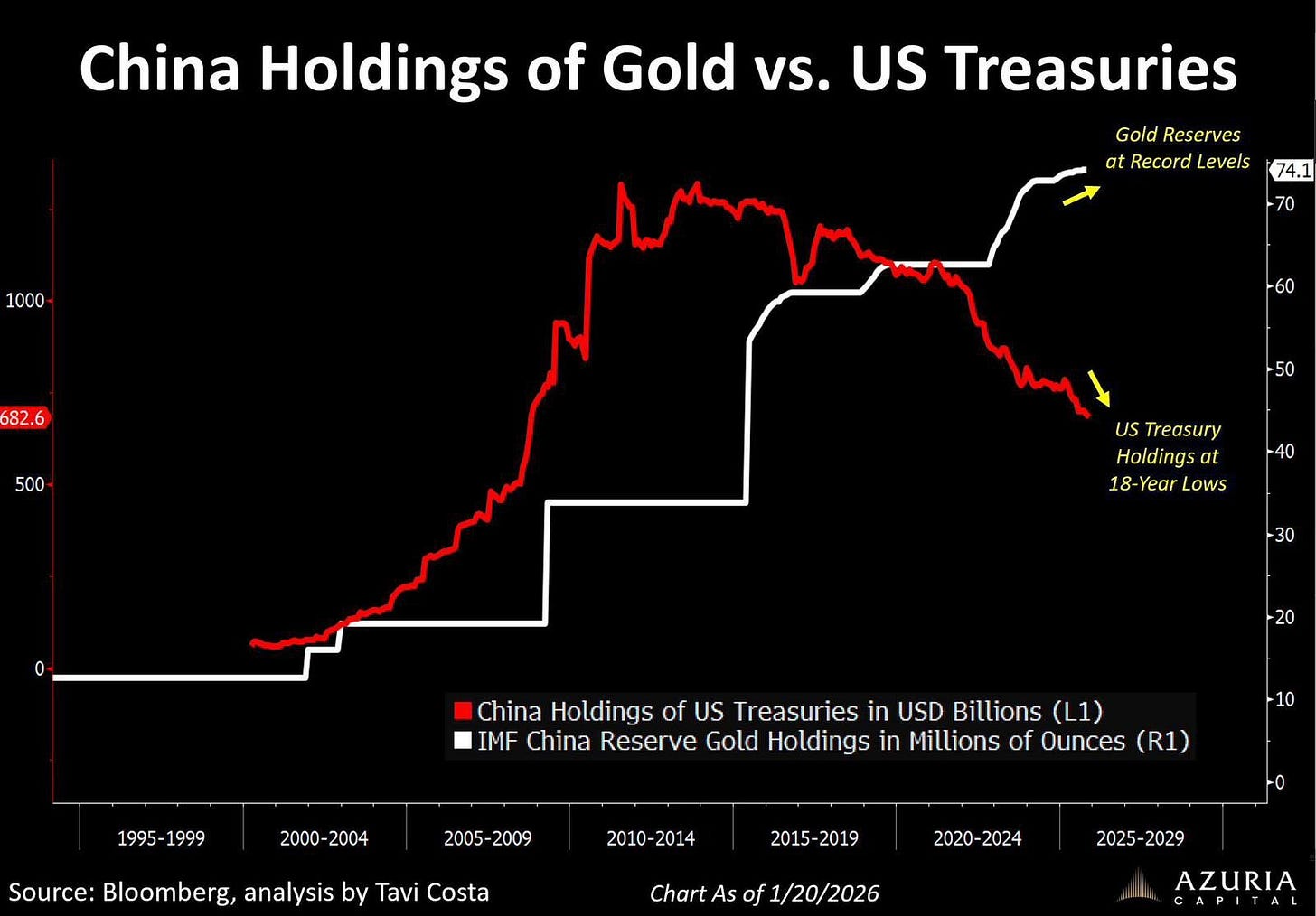

You see it in the gradual shift of reserve assets, where China – just like some Scandinavian pension funds recently –, has been reducing its holdings of US Treasuries while increasing gold reserves.

You see it in the growing emphasis on technological sovereignty, in the weaponization of sanctions and tariffs, in the slow fragmentation of supply chains. De-globalization is in full swing.

None of this implies imminent catastrophe. But it does imply that the probability of discontinuities is higher than it used to be just one year ago.

This is where my internal debate started to become concrete in light of the investment idea I have. The company I’m looking at is not just a random Chinese stock. It is a business with real earnings, a growing customer base, really fast growth (!), and a valuation that suggests the market is pricing in a lot of bad news already.

On paper, this is the kind of situation I usually like. A no-brainer. And yet, one detail kept bothering me: the lack of a dual listing. In a world where geopolitical tensions remain manageable, this is a footnote. In a world where financial infrastructure itself may become a tool of statecraft, a bargaining chip, it is something else entirely.

Suddenly, the question is no longer just whether earnings will grow or margins will expand. It is also whether ownership structures will remain intact, whether ADRs will continue to function as expected, and how different scenarios would play out if tensions escalated beyond what markets currently discount.

What makes this topic broader than a single stock is that the underlying dilemma applies to many Chinese equities today. Sentiment towards China has improved somewhat over the last year, and performance has been decent enough to challenge the narrative of permanent decline. At the same time, valuations remain somewhat compressed, capital flows are still somewhat cautious, and geopolitical risk is heightened. It is part of the discount rate you have to choose when investing in China.

The interesting question is not whether opportunities still exist in China. They clearly do. The question is how to think about them in a world where the assumptions of the last 30 years are slowly being renegotiated.

Before going any further, I should be explicit about one thing: Unlike some commentators who can apparently wake up one morning as a geopolitical expert, a currency strategist and a commodities analyst all at once, I’m painfully aware of the limits of my own circle of competence. I’m not a macro oracle. I don’t pretend to have privileged insights into military strategy or diplomatic chess games. My comparative advantage, if I have one, lies in analyzing companies, industries, and valuation dynamics. Everything I’m about to explore should be read through that lens. This is not an attempt to predict the future of global politics. It’s an attempt to connect the macro uncertainties of our time with the very concrete question of whether and how to invest in Chinese stocks.

Disclaimer: The analysis presented in this blog may be flawed and/or critical information may have been overlooked. The content provided should be considered an educational resource and should not be construed as individualized investment advice, nor as a recommendation to buy or sell specific securities. I may own some of the securities discussed. The stocks, funds, and assets discussed are examples only and may not be appropriate for your individual circumstances. It is the responsibility of the reader to do their own due diligence before investing in any index fund, ETF, asset, or stock mentioned or before making any sell decisions. Also double-check if the comments made are accurate. You should always consult with a financial advisor before purchasing a specific stock and making decisions regarding your portfolio.

Thoughts on the Non-Zero Taiwan Risk

If there is one thing I learned while thinking through the Taiwan question, it’s how easy it is to slide from analysis into narrative. I had a long conversation with a friend who owns Tencent and Alibaba via Hong Kong and has spent years thinking about China risk in a more pragmatic way than most Western investors. His view was not that a conflict is impossible, but that the way it is framed in Western media often borders on caricature. In his words, the probability of a Chinese move is non-zero, but the certainty with which headlines talk about an “inevitable invasion” says more about our own psychological need for simple stories than about reality.

And I agree, even though I will say it’s always hard to assess this objectively as someone living in the West with no boots on the ground. Historically, the Taiwan issue is more ambiguous than it is often portrayed. Taiwan’s status after World War II emerged from an unusual combination of Allied wartime declarations, the outcome of China’s civil war, and decades of geopolitical bargaining between Beijing and Washington. The People’s Republic of China has always considered Taiwan part of its territory, while the United States has maintained a deliberately ambiguous position, recognising Beijing diplomatically but committing itself to Taiwan’s defence in practice. This ambiguity is not an accident. It has been a stabilising mechanism for decades.

Both sides could maintain their narratives without forcing a decisive confrontation. From Beijing’s perspective, the long-term objective was never in doubt, but the timeline was flexible. From Washington’s perspective, ambiguity allowed deterrence without formal recognition of Taiwanese independence.

This is where the Western framing often becomes misleading. When Chinese officials talk about reunification, Western audiences instinctively translate that into imminent military action. But Chinese strategic culture is built around patience, rationality, incrementalism, and asymmetry in time horizons. The idea that a conflict can be postponed for decades is not seen as weakness in Beijing. It is seen as rational statecraft. If the balance of power is moving in your favour over time, why rush? Why gamble everything on a single dramatic event when demographic, economic and technological trends might deliver the outcome more cheaply later?

At the same time, it would be naïve to assume that rationality always prevails. History is full of examples where great powers miscalculated precisely because they believed they were acting rationally. The Taiwan Strait is not just a bilateral dispute. It is a focal point of global technological and military competition.

When the United States increases arms deliveries to Taiwan, it is not merely supporting a partner. It is signalling that Taiwan is part of its strategic perimeter. When China responds with military exercises, it is not merely posturing. It is testing thresholds, domestic legitimacy and external resolve. In such an environment, the risk of escalation does not come only from deliberate decisions. It also comes from misinterpretation, domestic political incentives and the inertia of security bureaucracies.

One argument that resonated with me is that risk tends to rise not where rhetoric is loudest, but where hardware accumulates. Conflicts rarely erupt in places devoid of weapons. They erupt where capabilities, expectations and political narratives collide. Ukraine is the obvious example. Taiwan is structurally similar in that sense. The steady militarization of the island is not proof that war is imminent, but it is proof that the option is being prepared for by all sides. Preparation itself changes incentives. It reduces the psychological barrier to action, even if the economic cost remains enormous.

Another dimension that is often overlooked in Western discussions is Taiwan’s internal politics. The island is not a monolithic actor. Its parliament is fragmented, and the balance of power is far more delicate than the usual “pro-independence versus pro-China” narrative suggests. The Democratic Progressive Party is currently the ruling party in Taiwan, leading a minority government that controls the presidency and the central government, while the opposition bloc led by the Kuomintang (KMT) holds a slightly larger share of seats, supported by smaller parties and independents. In other words, Taiwan’s political centre of gravity is neither firmly anchored in independence nor drifting towards unification. It is suspended in a state of managed ambiguity.

The KMT’s position is particularly instructive. It is more open to engagement with Beijing and more sceptical of outright independence than the DPP, but it is not necessarily best viewed as a vehicle for annexation. If the KMT were to gain more seats or regain the presidency, the most plausible outcome would probably not be a dramatic geopolitical shift. It would be incrementalism. Slightly warmer communication with Beijing. Symbolic gestures of de-escalation. Perhaps renewed cross-strait economic agreements. But ultimately, the KMT would remain trapped in the same structural dilemma as every Taiwanese government before it: avoiding both independence and unification.

Before we dive back in, a quick note…

Want to compound your knowledge – and your wealth? Compound with René is for investors who think in decades, not headlines. If you’ve found value here, subscribing is the best way to stay in the loop, sharpen your thinking, avoid costly mistakes, and build long-term success – and to show that this kind of long-term, no-hype investing content is valuable.

PS: Using the app on iOS? Apple doesn’t allow in-app subscriptions without a big fee. To keep things fair and pay a lower subscription price, I recommend just heading to the site in your browser (desktop or mobile) to subscribe.

From Beijing’s perspective, this is deeply unsatisfactory. The only outcome China is willing to accept in the long run is some form of political unification under its terms. Yet even the KMT is unlikely to endorse such a step. Even a historically symbolic figure, such as the current mayor of Taipei, who is widely seen as a potential KMT presidential candidate and a descendant of Chiang Kai-shek, would struggle to sell any meaningful concession on sovereignty to the Taiwanese electorate. At most, one could imagine a stepwise process: new cross-strait service agreements, deeper economic integration, perhaps limited Chinese participation in certain sectors like media. But those are evolutionary moves, not transformative ones. And they belong to a timeline that stretches beyond the next election cycle, perhaps into the late 2030s.

This is why Taiwan’s democracy is so geopolitically important. It produces outcomes that are stable but unresolved. Neither annexation nor independence, but a persistent equilibrium that frustrates Beijing and reassures Washington. For investors, that equilibrium is paradoxically stabilizing. It reduces the probability of sudden rupture while keeping the underlying conflict alive.

And yet, there is a variable that reshapes this entire equation: technology. Taiwan’s strategic importance is not only political, it is maybe even more so industrial. As long as the island remains indispensable to the global semiconductor ecosystem, it retains leverage that far exceeds its geographic size.

“The island is a microchip fabrication hotbed, producing 60% of the world’s semiconductors — and around 93% of the most advanced ones, according to a 2021 report from the Boston Consulting Group. The U.S., South Korea and China also produce semiconductors, but Taiwan dominates the market, which was worth almost $600 billion last year.“ - NBC News

But that leverage is not permanent. The United States is investing aggressively in domestic semiconductor manufacturing, not only for economic reasons but for strategic ones. If Washington were ever able to replicate a meaningful share of TSMC’s capabilities on its own soil – which seems very likely over the long run –, the geopolitical calculus would change in subtle but profound ways.

In such a world, Taiwan’s strategic value to the US would not disappear, but it would diminish. And if that happens, the implicit bargain between Washington and Beijing could shift. I don’t know if or when this scenario materializes. But it is hard to ignore the sense that there is a quiet race underway: China trying to reduce its technological dependence on the West, and the US trying to reduce its dependence on Taiwan. If both succeed partially, Taiwan’s unique position in the global system weakens. At that point, the idea of a “peaceful transition” stops being a moral question and starts (almost) becoming a strategic “win-win proposition.”

When I put all of this together, I end up with an uncomfortable but intellectually honest conclusion. A Taiwan conflict is neither inevitable nor unthinkable. It sits in a grey zone where probabilities matter more than certainties. For investors, this is the worst possible category of risk. It is too large to ignore and too uncertain to model with precision. And yet, it shapes the discount rate one needs to apply to every Chinese asset.

From here, the question becomes more concrete. If geopolitical risk is real but not binary, how should it influence the way I look at a specific stock? And how does the structure of ownership, listings and market access amplify or mitigate that risk? That is where the abstract debate about Taiwan suddenly turns into a very practical problem (for me).

Very Recent Developments: The Taiwan Risk Isn’t Static

While I was thinking through the Taiwan question, another development caught my attention: the downfall of Zhang Youxia. For years, he had been seen as one of the untouchables in China’s military hierarchy. A senior vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission, a veteran of the 1979 war with Vietnam, a long-time ally of Xi Jinping, and one of the few figures with both political weight and operational credibility inside the PLA (People’s Liberation Army). When even someone like Zhang is suddenly placed under investigation, it tells you that something deeper is going on beneath the surface.

The Economist described it as one of the most dramatic blows to China’s military leadership in decades. In a short span of time, Xi has effectively hollowed out the upper layers of the PLA, purging not only generals appointed by previous leaders but also many of his own protégés. From one perspective, this looks like a classic authoritarian consolidation of power. From another, it looks like a system under stress, where loyalty and competence are increasingly difficult to reconcile.

For investors invested in Chinese equities, the key question is not who wins factional battles inside the CCP. It is what these purges imply for China’s strategic capacity and its timeline.

On the surface, one could argue that an internally weakened military increases the temptation to externalize problems. History offers plenty of examples where domestic instability preceded foreign adventures.

But there is an equally plausible interpretation that points in the opposite direction. A military consumed by internal purges, mistrust, and organizational disruption is not an ideal instrument for a complex amphibious operation across the shallow Taiwan Strait. Even the Pentagon has hinted at this ambiguity, noting that corruption and leadership turnover may cause short-term operational disruptions, even if reforms eventually produce a more capable force.

“The Taiwan Strait, over ninety miles wide, is incredibly choppy, and due to two monsoon seasons and other extreme weather events, a seaborne invasion is only viable a few months out of the year.“ - from the article linked below

This is where I find the situation intellectually interesting. If Xi’s priority is regime security and internal control, then external risk-taking becomes less attractive in the near term. Purges absorb attention, create uncertainty within command structures and reduce the margin for error. A Taiwan operation would require not just political will, but extraordinary institutional coherence. The current trajectory suggests the opposite. In that sense, the Zhang Youxia episode may paradoxically reduce the probability of a near- and medium-term military move, even if it increases the sense that China is entering a more volatile phase.

Of course, the information environment around these events is polluted by speculation, rumours, and ideological projections, and after all, only Xi really knows what the long-term plan is.

Some narratives describe internal coups, secret arrests and imminent collapse of the CCP. Others portray Xi as an omnipotent strategist executing a flawless plan. Reality is almost certainly more banal and more complex. Power struggles exist, corruption persists, institutional reforms are incomplete, and the PLA is neither a paper tiger nor a perfectly oiled machine. For an investor, the only intellectually honest position is to treat extreme claims with scepticism while recognizing that structural fragility is real.