From Soros to Buffett: Exploring the Art and Science of Market Timing

Thou Shall Not Time the Market! (or Shall You?)

“The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.” —Marcel Proust

I stumbled across this gem in a tweet from John Mihaljevic recently, and it’s been rattling around in my head ever since.

As an investor, I’ve spent years honing a disciplined approach—buy quality businesses, hold them for the long haul, and let compounding do its work.

But lately, I’ve been wondering: have I found a way to see the market through new eyes? Or am I just tempting fate by questioning a sacred tenet of investing—that no one can time the market?

“I don’t think we would want a manager who thought he could just go to cash based on macroeconomic notions and then hop back in when it was no longer advantageous to be in cash. Since we can’t do that ourselves.” Charlie Munger

“We wish we had perfect market timing (as well as the ability to fly). The reality is that no one does or ever will.” Seth Klarman

I’m in the thick of wrestling with this idea, unsure if unlearning this critical lesson will sharpen my edge or lead me astray.

My gut leans toward “this will be to my detriment,” but I’m toying with the possibility nonetheless.

Let’s explore this together:

The Gospel of Patience—and Its Limits

For years, I’ve preached patience: invest in great companies, stay the course through volatility, and let time in the market weave its magic.

The data backs this up. Peter Lynch put it bluntly: “Far more money has been lost by investors preparing for corrections, or trying to anticipate corrections, than has been lost in corrections themselves.”

Studies—like those from Dalbar—show retail investors who try to time the market underperform buy-and-hold strategies by as much as 6% annually.

Even professional investors struggle; a 2018 analysis titled "Timing is money: The factor timing ability of hedge fund managers" by Gert Elaut, Péter Erdős, and Jonathan J. Szapáry, published in the Journal of Financial Economics, found that only 15% of hedge fund managers showed consistent timing skill over a decade.

TL;DR: For most, timing is a siren call to the rocks of underperformance.

I’ve built my investing life on fundamental analysis, picking winners, and letting them run. It’s a reliable path to beat the market by 2-5% annually—enough to build wealth over decades. Many successful investors who follow a similar philosophy have proven that fundamental analysis combined with a quality focus can lead to consistent market outperformance: I’m thinking of the likes of Terry Smith, Robert Vinall, or Dev Kantesaria.

But what if you want more? What if you aim to compress that journey into a shorter arc?

Buffett’s Quiet Timing—and Others’ Not-So-Quiet

When we think of market timing, the image often conjured is one of frenetic traders hunched over charts, chasing candlestick patterns and RSI crossovers. But the true masters of timing operate on a different plane.

Less noise, more signal.

Less frenzy, more calculated foresight.

Let’s pivot to a handful of legendary investors who’ve turned timing into an art form, some with bold strokes and others with subtle finesse. Stanley Druckenmiller, George Soros, Jesse Livermore, and—yes—even Warren Buffett offer a masterclass in reading the market’s pulse, each in their own distinct way.

The Loud Legends: Druckenmiller, Soros, and Livermore

Stanley Druckenmiller’s timing feats read like a financial thriller. He’s the maestro who shifted portfolios at market inflection points with surgical precision. His most famous coup? Shorting the British pound in 1992 alongside George Soros, pocketing $1 billion as the currency crumbled under pressure from overvaluation and economic missteps. But it’s not just one hit—Druckenmiller dodged bullets others couldn’t, sidestepping losses in the crashes of 1987, 2000, and 2008 without a single down year during those brutal stretches. His secret? A blend of macro insight, rapid adaptability, and an uncanny knack for sensing when sentiment had overstretched reality.

George Soros, Druckenmiller’s mentor and partner in the pound trade, painted with even broader strokes. Known for his macro bets, Soros thrived on exploiting global imbalances—currencies, bonds, equities, you name it. He didn’t just ride trends; he anticipated them, leveraging deep economic understanding and a willingness to bet big when the odds aligned. His timing wasn’t about charts—it was about seeing the world’s financial machinery grind toward inevitable breaking points.

Then there’s Jesse Livermore, the rogue genius of sentiment. Livermore rose to fame (and fortune) by surfing the waves of market psychology, most notably during the 1929 crash. He saw euphoria cresting and positioned himself to profit as it collapsed, amassing millions while Wall Street burned. But his story is a cautionary tale—his dramatic losses later in life underscore the razor’s edge of timing. Livermore’s gift was reading the crowd, but his downfall was failing to master himself.

These three wielded timing loudly, boldly, and—at times—recklessly.

Buffett’s Quiet Mastery

Warren Buffett, by contrast, is the quiet contrarian—the buy-and-hold sage who’d scoff at the notion of timing.

“Our favorite holding period is forever,” he famously quips.

But peel back the surface, and you’ll find a man who’s danced with timing more than he lets on, guided by valuation, sentiment, and a behavioral edge that rivals any trader’s gut.

Consider the evidence. In 1974, with stocks battered and fear choking the market, Buffett turned aggressive.

“I feel like an oversexed guy in a harem,” he told Forbes, scooping up bargains as others fled.

Fast forward to 1989: household equity exposure was low, signaling undervaluation, and Buffett pounced, loading up on Coca-Cola at a price that would define his legacy.

During the 2008–09 Great Financial Crisis, when panic peaked, he deployed billions—backing Goldman Sachs and buying stocks at fire-sale prices. Each move was a masterstroke of entry timing, cloaked as simple value investing.

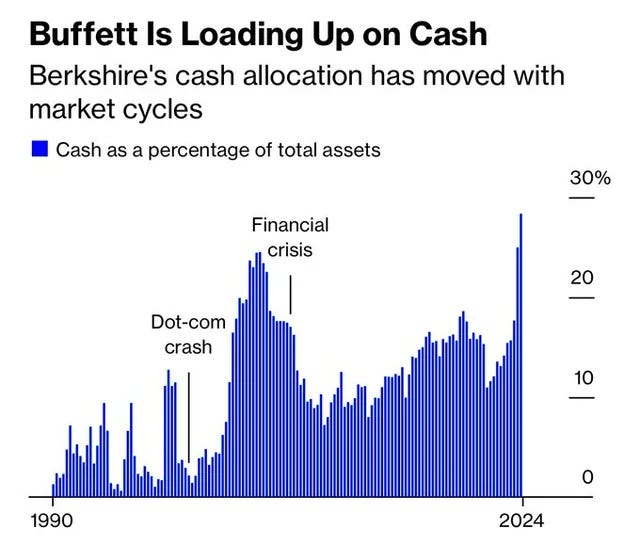

If anything, the numbers in the chart below could (or should?) be interpreted as a strong signal?

His exits—or lack thereof—tell a story, too.

In 1969, at the zenith of a euphoric bull market, Buffett liquidated his partnership, stepping away as valuations defied gravity. He dodged the ensuing crash, preserving capital for better days. In 1999, during the dot-com bubble’s second euphoric phase, he held firm—too firm, perhaps. He later regretted not selling holdings like Coke as mania peaked, admitting Charlie Munger convinced him to stay put. It’s a rare misstep he’s reflected on with candor.

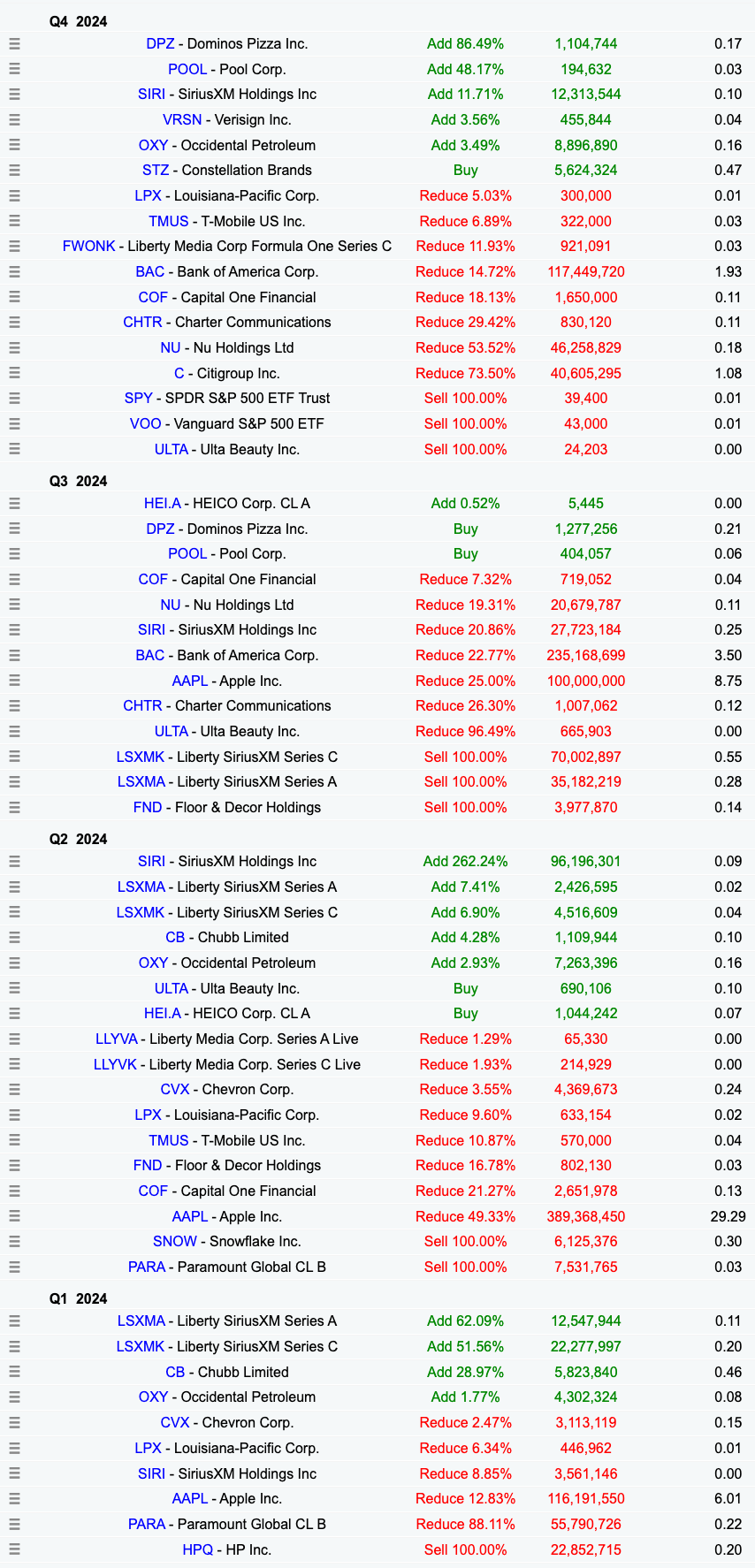

Today, in early 2025, we’re in what feels like a third euphoric wave—sky-high valuations, rampant optimism—and Buffett’s moves speak volumes. His cash pile has swelled to a reported $325 billion (almost 30% of Berkshire’s total assets), built through net selling in recent months (mainly Apple, which at one point represented more than 50% of Berkshire’s equity portfolio; now down to 28%).

He’s not calling a top with a megaphone; he’s quietly positioning, hoarding dry powder for when the pendulum swings back. Buffett doesn’t watch candlesticks or pore over moving averages. He reads the market’s emotional temperature—greed, fear, complacency—and aligns it with cold, hard valuation math.