[FREE] The Two Faces of Conviction: Speed, Patience, and What Really Wins in Markets

Shoot First or Study Forever?

There are countless ways to make money in markets. That’s obvious to anyone who has spent more than a few months watching how differently successful investors operate. Some swear by value, others chase growth. Some keep turnover low, others thrive on rapid trading. One group leans heavily into momentum, another obsesses over fundamentals.

Personality plays a huge role too. Some investors feel restless without constant activity, others are content to sit on their hands for years – I’m looking at you Norbert Lou and Guy Pier.

But beneath all the variety, I’ve come to believe there are timeless principles you simply cannot ignore if you want to last in this game and beat the market. Chief among them is the ability to stand apart from the herd. Every great investor has looked like a fool at one point or another – sometimes because the market lagged in catching up to their thesis, other times because the call really was foolish. Either way, success demands the willingness to act alone, absorb doubt, and tolerate discomfort.

One particularly interesting dimension where investors differ – and where I want to focus in this piece – is in how much fundamental work they need before pulling the trigger. Some investors require exhaustive research, others rely on a quick synthesis of a few crucial variables. Where you fall on this spectrum can determine not only your results, but also how much stress you endure along the way.

Here’s what I’ll cover:

Why Druckenmiller’s Nvidia story is such a revealing case study in fast, conviction-driven investing

How focusing on just a few critical variables often trumps information overload – and why more data can inflate confidence without improving accuracy

The virtues of the deep diver approach, and why some investors won’t touch a stock until they’ve built conviction through patient observation

The risks and trade-offs of both extremes – missing opportunities vs. blowing up on half-baked theses

How to identify where you fall on the continuum, and how to adapt your process as markets and personal circumstances evolve

Chapter 1: The Druckenmiller End of the Spectrum – Speed, Intuition, and Seizing the Moment

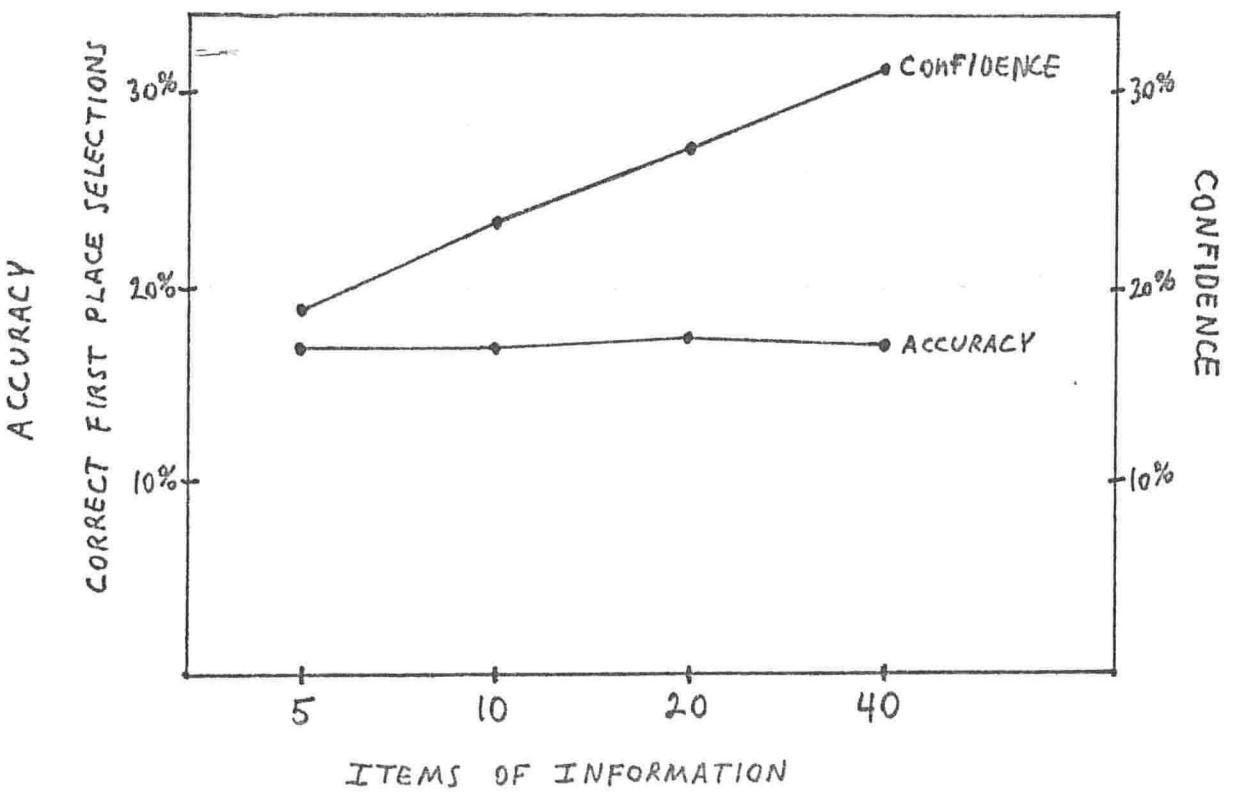

When I first listened to Stan Druckenmiller talk about his Nvidia trade, I was struck not just by the outcome, but by the process. He didn’t arrive at the trade after months of deep research or by building a discounted cash flow model. Instead, the seed was planted in a conversation with his young partner in the fall of 2022. The partner argued that all the blockchain hype was going to be dwarfed by artificial intelligence and suggested Nvidia as the way to play it.

Druckenmiller admitted he “didn’t even know how to spell it” (that line gets me laughing out loud every time!). And yet, he bought it anyway.

A month later, ChatGPT exploded onto the scene, giving him the validation he needed to increase his position substantially. By June 2023, he was openly calling AI a megatrend “potentially bigger than the Internet.” That trade worked out spectacularly.

But the fascinating part isn’t the profit – it’s the process. Druckenmiller acted quickly, without full information, and let the conviction build as the evidence rolled in.

That approach embodies a philosophy you see in many great traders: you don’t need every data point to take action. In fact, waiting for perfect information often means missing the move. What matters more is recognizing when the world has shifted, isolating the handful of variables that really drive the thesis, and then betting with size before the rest of the market catches on.

Druckenmiller has a long history of doing this, from shorting the British pound in 1992 to catching the tech wave of the late ’90s. He’s built a career not by having the most complete dataset, but by having the sharpest intuition about turning points.

Of course, intuition is a slippery word. It makes people think of gut feel, or worse, of recklessness. But intuition, in the hands of someone like Druckenmiller, is really a synthesis of decades of pattern recognition. It’s more about pattern recognition than actual gut feeling.

He has spent his life watching markets, internalizing how they behave, and cataloging the subtle signs that precede a major shift. When you’ve put in that kind of time, what looks like “shooting from the hip” is often a deeply informed judgment call.

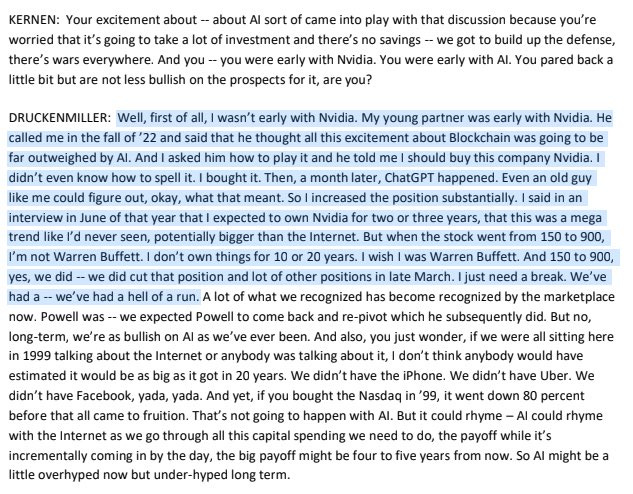

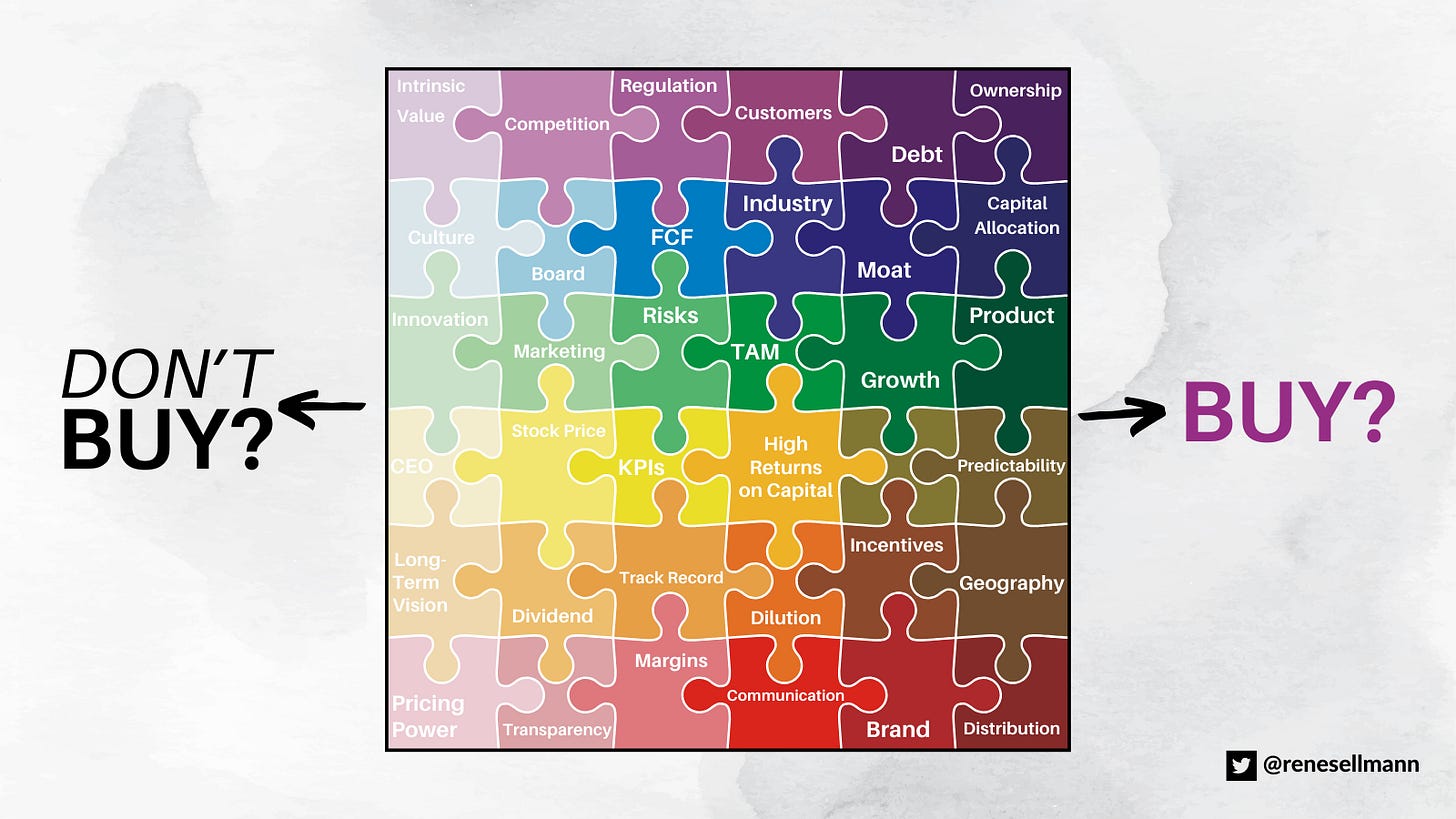

The challenge, of course, is separating useful intuition from impulsive decision-making. This is where that chart (see below) that Tiho Brkan often shares becomes so relevant.

It shows that as investors consume more and more information, their accuracy barely improves – but their confidence shoots through the roof.

The implication is dangerous. Too much information doesn’t necessarily make you right, but it makes you feel right. And that can be catastrophic.

Druckenmiller sidesteps this trap by cutting through the noise. Instead of drowning in reports, he zeroes in on the two or three KPIs that really matter. With Nvidia, those drivers were crystal clear: AI demand and Nvidia’s position as the only scalable supplier of the necessary GPUs. Everything else was secondary.

Before we dive back in, a quick note…

Want to compound your knowledge – and your wealth? Compound with René is for investors who think in decades, not headlines. If you’ve found value here, subscribing is the best way to stay in the loop, sharpen your thinking, avoid costly mistakes, and build long-term success – and to show that this kind of long-term, no-hype investing content is valuable.

The other lesson here is speed. In markets, timing matters. Paradigm shifts don’t wait for your spreadsheets to balance. You can make a lot of money at turning points. But by the time the consensus has built a complete case, the opportunity is often gone.

Druckenmiller himself compared it to buying the Nasdaq in 1999: even if you were right about the long-term impact of the Internet, the entry point made all the difference. The same is true for AI today. If you waited until every major bank had published a deep dive on Nvidia, the stock had already gone from 150 to 900 (before the 2024 10-for-1 split).

But speed cuts both ways…

For every Druckenmiller who nails a turning point, there are countless investors who chase a narrative too early or too late, without enough discipline to exit when the thesis cracks.

Acting fast magnifies both upside and downside. Druckenmiller admitted himself: “I don’t own things for 10 or 20 years. I wish I was Warren Buffett.” That admission underscores the trade-off. His edge lies in moving quickly and decisively, not in holding indefinitely.

If you’re naturally inclined toward this style, the key is to build systems that protect you from the downside of speed. That might mean position sizing smaller until conviction grows, or being ruthless about cutting losses. It might mean constantly asking yourself whether you’re trading intuition or just getting swept up in the zeitgeist.

The difference is subtle but crucial.

When I think about Druckenmiller’s Nvidia story, I don’t just see a lucky trade or a well-timed bet. I see the distilled essence of a style of investing that prioritizes speed, clarity, and conviction over exhaustive analysis. It’s a style that thrives on big themes, asymmetric setups, and the willingness to act before the crowd has even grasped what’s happening.

(Druckenmiller’s Nvidia discussion at the podcast of the Norges Bank Investment Management starts at 12:38 in the video above)

Chapter 2: The Deep Divers – Patience, Conviction, and the Weight of Evidence

If Druckenmiller represents one extreme of the spectrum, then at the other end you’ll find the deep divers. These are the investors who don’t act until they’ve built a fortress of conviction, brick by brick. They’re not in a rush to own the hottest stock of the moment. In fact, they often let opportunities pass by because they aren’t yet convinced they understand the business well enough.

For them, patience isn’t a tactical choice – it’s the foundation of their process. It’s their strength.

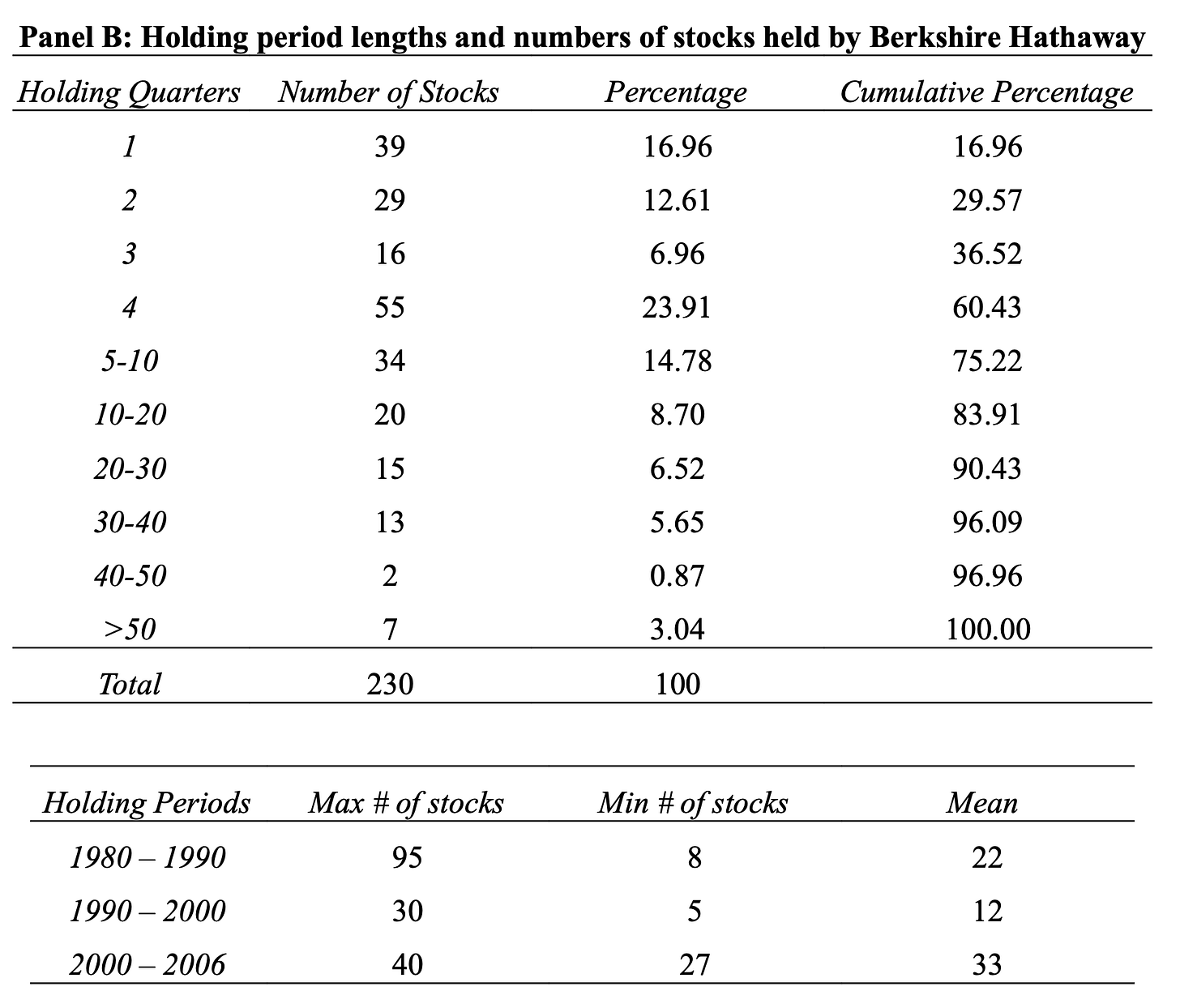

Think of Warren Buffett quietly circling a company for years before making his move. By the time he finally writes the check, he knows the business inside out. He has watched management execute across multiple cycles. He has studied the competitive dynamics, understood the economics in excruciating detail, and assessed the long-term runway for growth. When he does buy, it’s usually with the intention of holding for decades, not months. In practice, he’s exiting most of his holdings fairly quickly, though. So while I’d put Buffett towards the other end of the spectrum discussed, he’s certainly representing the extreme end point.

This approach creates a very different rhythm. Instead of racing to catch a paradigm shift, deep divers cultivate a slow accumulation of evidence. They read annual reports of the last decade (or two if needed) – and then they move on to the competitors and do the same... They attend industry conferences, not for the hype, but to quietly map out how the ecosystem fits together. They track a handful of KPIs over years, waiting to see how management responds when times get tough. The position often starts small, sometimes just a placeholder, but grows as the mosaic fills in.

The advantage of this style is obvious: conviction. When you’ve done this much work, you’re less likely to be shaken out by volatility or short-term noise. You’ve anchored your thesis in fundamental reality rather than in narrative momentum. That makes it possible to hold through drawdowns that would terrify others. If you’ve already thought through the risks, tested the downside scenarios, and know the cash flows can weather storms, then a 30% sell-off looks less like a disaster and more like a chance to add.

But deep diving isn’t without its flaws. The most common is analysis paralysis. When you demand perfect clarity, opportunities often slip away before you can act. By the time you’ve mapped out every competitor, the stock may already have doubled. Another risk is overconfidence in the depth of your own research. Spending years on a company can blur the line between insight and attachment. Sometimes the deeper you go, the harder it becomes to admit you might be wrong.

And there’s another subtle danger: mistaking information for edge. Remember that chart from above – accuracy flatlining while confidence soars as information piles up? Deep divers are especially vulnerable to this trap. More research feels like progress. More files, more transcripts, more conversations with management and other investors. But if the marginal piece of information doesn’t change your thesis, it may just be adding comfort rather than clarity and deeper insight.

Still, there are periods when this style massively outperforms. Consider long stretches of grinding markets where hype cycles burn out and only fundamentals matter – it’s been a while, I know... But in those environments, deep divers shine. They’re not chasing fads; they’re quietly compounding wealth through businesses they understand deeply. The gains may come slower, but they often prove more durable, and downsides are limited.

What fascinates me about this style is how personality-driven it is. Some investors simply can’t operate without certainty. They need the security of knowing they’ve covered every angle before risking capital. For them, Druckenmiller’s Nvidia trade would feel reckless, even irresponsible. But for the deep diver, that’s the point: their advantage isn’t speed – it’s endurance, and patience!

They win not by getting in early, but by holding on long after others have lost faith.

Chapter 3: Finding Yourself on the Continuum

When you look at the two ends of the spectrum – the quick shooter who thrives on speed and intuition, and the deep diver who builds conviction through relentless study – it’s tempting to ask which one is better?

That’s the wrong question. The real question is: which one are you?

Self-awareness is the underrated edge in investing. If you’re wired like Druckenmiller, forcing yourself into a Buffett-style waiting game will probably leave you frustrated and underutilized. You’ll end up second-guessing yourself, paralyzed by the need for more information. On the other hand, if your natural temperament is to comb through every filing and stress-test every assumption, trying to mimic Druckenmiller’s rapid-fire style will feel like gambling. You won’t be able to hold on when things get rough, because you didn’t build conviction in a way that suits you.

What makes this interesting is that neither style is static. Investors evolve.

Most of us, over time, will find ourselves shifting along the spectrum depending on the opportunity set, our life stage, and even our psychological bandwidth. Early in your career, when you’re eager to prove yourself, you might be more of a quick shooter. Later on, with more capital to protect, you might gravitate toward the slow build of the deep diver.

That flexibility is key, because markets themselves don’t sit still. In a fast-moving technological revolution, being able to synthesize quickly and act decisively can be a massive advantage. But in a slow, grinding bear market, the investors who have the patience to sit with deeply researched companies often come out ahead. Knowing when to lean into one style or the other is an art that can’t be outsourced.

There’s also the matter of risk management. If you lean toward the Druckenmiller side, you need systems to keep the downside in check – strict position sizing, willingness to cut losses, clarity on what would invalidate your thesis. If you lean toward the Buffett side, you need to watch for the traps of over-research – getting stuck in analysis, mistaking familiarity for safety, or refusing to sell when the facts change.

The continuum isn’t a binary choice. You can, and probably should, borrow from both ends. Think about this for a moment..

Maybe you start small and fast when a big theme emerges, then gradually scale as your conviction builds.

Maybe you keep a core of long-term compounders you’ve researched deeply, while reserving a portion of your portfolio for opportunistic, quicker trades.

The blend depends on who you are and what you’re trying to achieve.

So if you take nothing else from this, take this: don’t try to be Druckenmiller, and don’t try to be Buffett. Figure out where you sit on the continuum, lean into your strengths, and build safeguards around your weaknesses. That self-knowledge will do more for your long-term returns than any hot stock tip ever could.