[FREE] The Investor’s Real Edge? Subtraction

Unlearning to Win: How to Build a Clearer Investing Process

Note: The voiceover above is a custom-made, slightly adapted version of the blog post, edited for a smoother and more engaging listening experience. It’s one of the perks available to paid subscribers, as I’m always focused on adding as much value to my subscribers as possible. Enjoy!

When I first got into investing, I did what almost everyone does: I became a vacuum cleaner. I inhaled everything I could find – books, podcasts, YouTube channels, blogs, Twitter threads, even financial news networks I now consider borderline unwatchable. I figured the more I consumed, the faster I’d level up. More input, more insight, more results. That was the logic.

And to be fair, it wasn’t a mistake. In the early days, that kind of obsessive curiosity is more feature than bug. It’s how you get exposed to different schools of thought. It’s how you figure out who’s thoughtful and who’s loud. And it’s how you start developing your own taste.

But here’s the thing: nobody tells you when to stop vacuuming. And if you don’t, you’ll eventually find yourself stuck with a mind cluttered by contradictions, half-baked strategies, shallow heuristics, and all kinds of seductive nonsense that feels actionable but rarely is. That’s when something has to change.

You stop vacuuming, and you start flushing.

Crude as it may sound, becoming a toilet flush is a much more accurate metaphor for long-term investing success. You start actively discarding ideas, content, frameworks, and even mentors that don’t stand up to scrutiny – or that simply don’t fit your personality. You shift from learning by addition to learning by subtraction. From seeking new inputs to filtering aggressively.

It’s not an easy transition. In fact, unlearning can be far harder than learning. But if you want to build a robust, coherent investment process – one that can survive market cycles and psychological stress – you need to stop hoarding ideas and start curating them.

In this post, I’ll walk you through that evolution:

How the early vacuum phase seduces almost every investor—and why it’s not all bad

Why investing is filled with “anti-patterns” that sound smart but consistently mislead

What makes unlearning so hard—and why it’s where real progress begins

How to identify and flush what doesn’t serve you

And finally, how to build your own investing operating system by filtering out the noise and focusing on just a few reliable sources

Before we dive back in, a quick note…

Want to compound your knowledge – and your wealth? Compound with René is for investors who think in decades, not headlines. If you’ve found value here, subscribing is the best way to stay in the loop, sharpen your thinking, avoid costly mistakes, and build long-term success – and to show that this kind of long-term, no-hype investing content is valuable.

Thank you for your support!

The Vacuum Phase – When More Feels Like Progress

There’s something thrilling about discovering investing for the first time. It’s like someone hands you the keys to a secret world. A world where, with enough knowledge and skill, you can compound your money, escape the rat race, and gain autonomy over your life.

It’s a powerful promise. And that’s exactly why the early phase of an investor’s journey often turns into a full-blown obsession.

So you do what any curious, motivated person would do: you start vacuuming. You read the classics and the trendy new releases. You subscribe to half a dozen newsletters. You binge podcast episodes during your commute and go down YouTube rabbit holes late at night. You search for podcasts with “dividend” in their show’s name. You follow big-name investors on Twitter, get into arguments in comment sections, maybe even dabble in Reddit threads.

It feels like progress. And in some ways, it is. You’re building mental scaffolding. You’re getting a feel for terminology, frameworks, and market history. You’re starting to recognize names, strategies, and opposing philosophies. Growth vs. value, Buffett vs. Greenblatt, index vs. active, technicals vs. fundamentals – over time, it all starts clicking.

The problem is, this phase doesn’t come with a built-in filter. You’re exposed to everything, from timeless wisdom to borderline financial snake oil. Some of it contradicts itself. Some of it sounds brilliant but falls apart under stress. And some of it might work well in theory – but not for you!

Because here’s the first major lesson that gets lost in the vacuum phase:

Just because something works for someone else doesn’t mean it will work for you.

It’s easy to underestimate how much personality plays into investing. Some people thrive in uncertainty. Others don’t. Some enjoy high-stakes concentration. Others sleep better with broad diversification. Some are wired to lean into volatility. Others flinch the moment a stock drops 15%.

None of this is wrong – it just means that fit matters. And early on, you’re not optimizing for fit. You’re optimizing for volume.

The other hidden danger? Conflicting inputs that erode your ability to think independently. If you follow ten different people who each have a slightly different view of what matters most – revenue growth, ROIC, margin expansion, TAM, insider buying, macro tailwinds, price momentum – you’ll struggle to know which lens to prioritize. You start grabbing concepts off the shelf like ingredients for a meal you’ve never cooked, hoping the end result will taste like wisdom.

It doesn’t.

Instead, you’re left with a cluttered mental model – one that’s too messy to act on, but too familiar to throw out. That’s the point where a lot of investors stall. Not because they lack information, but because they’ve accumulated too much of it – and it’s pointing in too many directions.

The vacuum phase gets you moving, but it doesn’t get you far. To evolve, you have to let go of the idea that more is always better. You have to learn what to keep – and what to flush.

Learning by Subtraction – Why Unlearning Is Harder than Learning

There’s a quote from Charlie Munger that has stuck with me for years: “It’s not the learning that’s so hard. It’s the unlearning.” And if you’ve been investing for a while, you know exactly what he means.

By the time you’ve vacuumed your way through dozens of books, hours of content, and countless market opinions, your brain isn’t just full – it’s cluttered. You’re not operating with a clean, elegant investment framework. You’re carrying around a Frankenstein’s monster of half-digested ideas, conflicting signals, and mental shortcuts that may or may not hold up in real-world conditions.

The issue isn’t just that some of these ideas are wrong. It’s that many of them are almost right. They sound smart. They feel intuitive. They worked once, maybe twice. But over time, you realize they don’t stand up to scrutiny – or worse, they lead you into traps. That’s when the real work begins: unlearning what’s not helpful, even if it once felt profound.

This is where a lot of people get stuck. Because unlearning isn’t just a cognitive task. It’s emotional.

You spent time and energy learning that stuff. You may have built an identity around it – “I’m a GARP investor” or “I follow macro” or “I believe in moats above all else.” Walking away from that isn’t easy. It feels like wasted effort (sunk cost fallacy). It forces you to admit, at least partially, that you were wrong.

And yet, if you don’t do it, you stay trapped. You keep reacting to old signals that don’t work anymore. You keep following outdated rules. You keep investing according to someone else’s philosophy – usually a stranger whose time horizon, temperament, and goals are nothing like yours.

That’s why the toilet flush metaphor matters. Because flushing isn’t passive. It’s decisive. It’s intentional. You’re saying: “This idea doesn’t belong in my process anymore.” Not because it’s inherently bad, but because it doesn’t help you make better decisions with your capital, in your market environment, with your psychological makeup.

I had a conversation with a friend – Tiho Brkan – who put this perfectly. He told me that early on, he was a vacuum learning machine. He inhaled everything. But now? Now he learns by subtraction. He actively flushes anything that doesn’t work in practice. Especially things that sound good on paper but don’t hold predictive power in the real world.

He called many of them anti-patterns – seemingly smart solutions that are actually harmful. And once you start seeing them, you can’t unsee them.

But before we go there, it’s worth pausing on this idea:

Subtraction is a skill.

It’s not just about skepticism. It’s about discernment.

It’s the ability to spot what’s essential, discard what’s not, and keep your mental operating system clean.

In the end, what separates good investors from great ones isn’t just how much they’ve learned. It’s what they’ve chosen to unlearn.

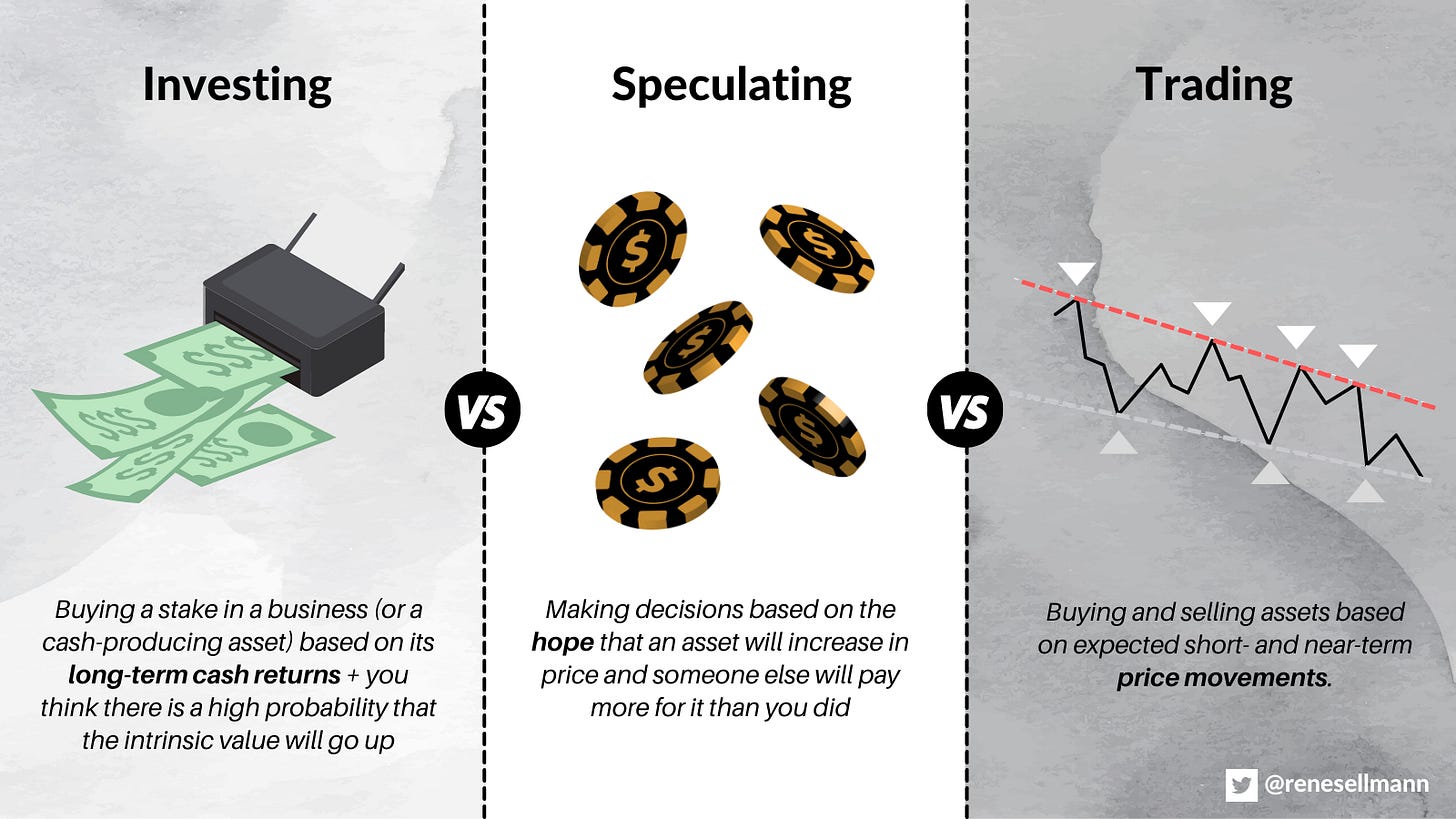

The Problem with Anti-Patterns – And Why Most Content Is Flawed

By the time you’ve been around the investing block a few times, you start to notice a strange phenomenon: a lot of advice that sounds smart, polished, and well-packaged just doesn’t work. Not in the real world. Not in real portfolios. Not over time.

That’s because a huge portion of financial content is built on anti-patterns – ideas that appear useful on the surface but are ultimately misleading, overly simplistic, or outright counterproductive. It’s what the masses are drawn to.

The term comes from architecture and software design. In those fields, a “design pattern” is a proven solution to a common problem. An “anti-pattern,” on the other hand, looks like a solution but fails repeatedly in practice. It might be popular, it might spread easily, but it doesn’t actually work once it’s implemented.

Investing is full of these.

Take the idea that revenue is everything. You’ll hear this often in growth circles, on Twitter, and even in some venture capital blogs. Revenue, revenue, revenue. Sounds good, right? After all, no company survives without top-line growth.

But as a standalone metric? It’s a terrible compass. It ignores profitability, capital intensity, pricing power, competitive dynamics, and a dozen other variables that actually determine long-term shareholder value.

Yet this “growth is everything” narrative continues to spread, especially in frothy markets. It’s an anti-pattern – a seductive shortcut that skips the hard work of real analysis.

Another common one: “Buy what you know.” Popularized by Peter Lynch, and totally misunderstood. What Lynch meant was to use your personal experience to spot potential opportunities – not to blindly invest in your favorite brands without a rigorous process. But the simplified version is easier to repeat, so it spreads. And suddenly, someone’s building a portfolio of Netflix, Nike, and Starbucks, thinking they’re practicing due diligence.

There’s a reason these anti-patterns thrive: they’re easy to remember, emotionally satisfying, and promise clarity in a complex world. But investing isn’t simple. It’s messy. It involves trade-offs, context, nuance, and most of all, time. Any framework that glosses over those elements should be treated with extreme caution.

The other issue is that content quality is inversely correlated with virality. The more nuanced and thoughtful a piece of research is, the harder it is to package it into a TikTok, a thumbnail, or a 30-second soundbite. Meanwhile, the loudest voices often win attention – not because they’re right, but because they’re confident.

That’s why the flush matters.

You need to develop the instinct to question even good-sounding advice. You need to ask: Does this have predictive power? Has this worked across cycles? Is it compatible with how I actually think and invest? And most importantly: Can I see myself relying on this when the stakes are high and the pressure is real?

Because that’s the test. When the market turns, when your portfolio’s in the red, when the temptation to react is strongest – that’s when anti-patterns do the most damage. They give you just enough confidence to act, but not enough substance to act wisely.

So yes, flush aggressively. But flush thoughtfully. Don’t just discard ideas because they’re trendy or contrarian. Discard them because they don’t serve your process. Because they fail the test of real-world utility. Because they distract more than they clarify.

The goal isn’t to be a contrarian for its own sake. It’s to build a mental operating system that can actually make decisions under pressure. And that only comes from clearing out the clutter.

Coherence Matters!

At some point, if you stick with investing long enough, you stop trying to copy other people’s playbooks. You stop chasing every new strategy, every hot take, every clever thread. You realize you don’t need more inputs – you need a better filter. Having a strong filter is a superpower. Say “no” to almost everything.

And to do that, you need coherence. A personal investing philosophy that fits your temperament, your goals, your time horizon, and your edge – whatever that may be. Not someone else’s edge. Not someone else’s backtested model. Yours.

This is where subtraction becomes a superpower.

Instead of asking, “What else should I be reading?”, you start asking, “What do I already know that actually helps me?” Instead of following ten different content creators, reading books from 20 different authors, listening to 15 different podcasts – all with conflicting styles –, you narrow it down to two or three whose frameworks you deeply respect. And then you go deep.

That’s what I’ve done. My short list includes Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger, and Michael Mauboussin. Occasionally I’ll throw in someone like Rob Vinall, Geoff (from Focused Compounding), Chris Mayer, or Chuck Akre, but that’s about it. I’ve read almost everything they’ve put out. And I re-read it. Not once. Dozens of times. Not because I’m looking for a new insight every time – but because I want to internalize the mindset, the frameworks, the priorities.

It’s not about chasing novelty. It’s about deepening conviction.

When you read Buffett’s old shareholder letters again and again, you start to hear his voice in your head when analyzing a business. When you study Mauboussin’s work on expectations, complexity, and base rates, you start to see patterns others miss – not because you’re smarter, but because your lens is sharper.

You don’t need fifty inputs. You need five that actually matter. Maybe fewer. What matters is that they align with how you think. That they push you toward clarity, not confusion. That they help you focus on the handful of things that actually drive long-term outcomes – things like capital allocation, moat durability, reinvestment runway, pricing power, and incentives.

And that focus? That’s your edge.

The longer I invest, the more convinced I am that most underperformance comes not from missing great ideas, but from chasing too many of them. From switching frameworks every few months. From second-guessing your own instincts because someone online made a louder case.

It’s easy to forget, but investing is not a group project. You don’t get points for reading the most, following the best thinkers, or using the latest tools. You get rewarded for clear thinking, rational behavior, and patience. And all of those require an uncluttered mind.

So flush what’s not serving you. Re-read what is. And build a system that fits your DNA.

You don’t need more information. You need better filters.