[FREE] Flexing a Moat Too Hard? How Twitch Lost What Looked Unbreakable!

A Case Study In Competitive Dynamics: Why Kick Could Buy What Money Usually Can’t!

Note: The voiceover above is a custom-made, slightly adapted version of the blog post, edited for a smoother and more engaging listening experience. It’s one of the perks available to paid subscribers, as I’m always focused on adding as much value to my subscribers as possible. Enjoy!

For a long time, Twitch was a bit of a black box to me. It was one of those platforms that my students talked about constantly but that I never personally used. They’d mention streamers or live events I’d never heard of, and I’d nod politely, feeling that quiet generational gap you sometimes notice when talking to teenagers.

YouTube I understood. But Twitch? It seemed like something that belonged to a different media universe.

It reminded me of that realization many people my age have when they catch themselves saying what their parents once said about them. For my parents’ generation, the idea of spending five hours going down a YouTube rabbit hole about a random niche topic is almost unimaginable. For mine, Twitch was starting to feel like that same mystery – something that clearly mattered culturally but was hard to intuitively grasp.

Then the pandemic hit, and, like many people, I started consuming more online content than I’d like to admit. Somewhere along the way, YouTube’s algorithm decided I should watch Counter-Strike videos. Not tutorials or highlight reels – professional matches. And over time, it worked. I developed an interest in the esport, followed some of the teams more closely (spoiler: the two teams I “picked” have mostly been losing ever since), and began watching full games.

That’s when I inevitably ended up on Twitch, since a good amount of tournaments were streamed exclusively there. It felt like stepping into a parallel internet where chat scrolls like a river, emotes replace sentences, and communities operate at lightning speed.

Fast forward to this year, and I started noticing something strange. Certain tournaments I wanted to watch weren’t on Twitch anymore – they were Kick exclusives. I’d never even heard of Kick until then, and yet here it was, somehow attracting major esports broadcasts within a few short years of launching.

That curiosity, in turn, brought me to this post.

What makes the Twitch story fascinating from an investor’s perspective is that I’d never actively thought about it through that lens before. It isn’t a standalone stock; it’s part of Amazon’s vast conglomerate. Within Amazon’s ecosystem, Twitch is too small to move the needle. But as a case study in competitive dynamics, moat management, and platform fragility, it might be one of the most instructive businesses to analyze.

When you study Twitch, the businesses, what should strike you is the density of its network effects. In most digital networks, the logic is simple: more users attract more creators or suppliers, which in turn attracts more users. But live streaming amplifies this in a very particular way. Twitch didn’t just have users and creators – it had communities. And communities compound much faster than networks.

Every additional streamer didn’t simply add more content; they created another micro-ecosystem. Viewers didn’t just consume – they chatted, clipped, donated, moderated, and built inside jokes that made each channel feel like a living organism. That constant feedback between creator and viewer formed the beating heart of Twitch’s moat. It’s one thing to host a library of videos. It’s another to host a living audience that shows up simultaneously, interacts with each other, and then comes back tomorrow.

For years, that structural feature made Twitch feel unbeatable in the live space. By 2021, it commanded around 90% market share in live game streaming. Competitors like Mixer (Microsoft) or Facebook Gaming tried and failed, even with enormous financial backing.

Each underestimated how much of Twitch’s moat was cultural & network-based, not technological. You can build the same servers; you can’t replicate the same inside jokes, memes, or rituals that animate a chat at 2 a.m. during a streamer’s marathon session.

When network effects are this strong, they can’t be broken. They pull creators and viewers into orbit, and once that orbit stabilizes, it’s almost impossible to escape. That’s what made Twitch look, for years, like the perfect compounding asset inside Amazon’s portfolio (Amazon acquired Twitch for $970 million in an all-cash deal in 2014).

The platform’s economics scaled beautifully: minimal marginal cost per stream, strong data network effects feeding discovery algorithms, and the optionality of ads layered on top of subscriptions and bits. From the outside, it seemed like a textbook example of how to convert social energy into financial leverage.

But if you zoom in, there was a fragility built into that structure. Live networks depend not only on scale but on goodwill. A creator doesn’t have to move to a new platform entirely—just streaming a few hours elsewhere each week is enough to fragment their audience, to thin out the density that makes Twitch special. Viewers aren’t permanently locked in either; they’re loyal to people, not platforms. Twitch’s moat looked like an iron wall, but it was really a dense web of voluntary connections. Pull on a few threads hard enough, and the web starts to loosen.

That’s what makes this case fascinating to me as an investor. On paper, Twitch had every structural advantage you’d want: network effects, scale economies, switching costs, brand recognition, and integration inside a deep-pocketed parent. And yet within just a few years, a challenger born in 2022—Kick—was able to seize a non-trivial slice of market share.

To understand how, we have to examine what happens when a company starts treating its moat not as something to nurture but as something to monetize aggressively. Because when you over-extract from a network built on goodwill, the physics change.

When an Advantage Becomes a Tax – How Over-Flexing Weakens the Moat

So at its peak, Twitch was a dream case study in how network effects create near-unassailable dominance.

But the flip side of that dominance is temptation. Once a company realizes it can raise its “take rate” or tighten policies without immediate defection, it often starts testing how far it can push before the ecosystem revolts. In other words, an advantage gradually turns into a tax.

Twitch’s first warning signs were subtle. For years, top creators had enjoyed a 70/30 subscription revenue split – the same basic deal that defined its early success. Then, in 2023, Twitch announced that the standard would shift to 50/50 for most partners.

The move was framed as a rebalancing: higher infrastructure costs, more moderation expense, and a desire to standardize contracts.

But the message creators heard was different. It said:

“We think you have nowhere else to go.”

Around the same time, Twitch introduced stricter ad-placement rules, new guidelines around sponsorships, and moderation policies that alienated segments of its community.

The logic from the inside probably looked rational: higher monetization per viewer, better brand safety, less regulatory risk. Yet, these changes chipped away at the implicit social contract between the platform and its creators. The network that once felt symbiotic began to feel extractive.

What’s tricky about live networks is that they rarely show early quantitative warning signs. Engagement might stay high even as dissatisfaction simmers beneath the surface. The data lags the mood. A few high-profile streamers leaving doesn’t change aggregate viewership overnight, but it alters sentiment in ways that cascade later. The moment creators start asking themselves whether they have to stream on Twitch or whether they want to, the flywheel begins to wobble.

In hindsight, Twitch’s mistake was managerial more than strategic. The team correctly recognized its pricing power but underestimated how fragile that power was. Network effects don’t exist in a vacuum; they rely on voluntary participation. You can think of it as a loop made of rubber bands, not steel links. Every time you tighten a policy or take a higher cut, you stretch those bands. At first, the tension adds resilience – the system can handle it. But keep pulling, and eventually one snaps.

The cultural fabric of Twitch was also changing. What began as a quirky gaming community matured into a massive commercial ecosystem. With that scale came corporate caution. Twitch had to please advertisers, regulators, and parent company shareholders. The raw authenticity that once defined it was gradually professionalized out of existence. Streamers who thrived on spontaneity found themselves navigating a growing maze of compliance boxes to tick.

Meanwhile, the platform’s engagement metrics had quietly plateaued. By mid-2023, total hours watched across the industry were still growing, but Twitch’s share was slipping. Competitors like YouTube Gaming were stable, yet a new entrant, Kick, was suddenly accounting for meaningful percentages of viewership.

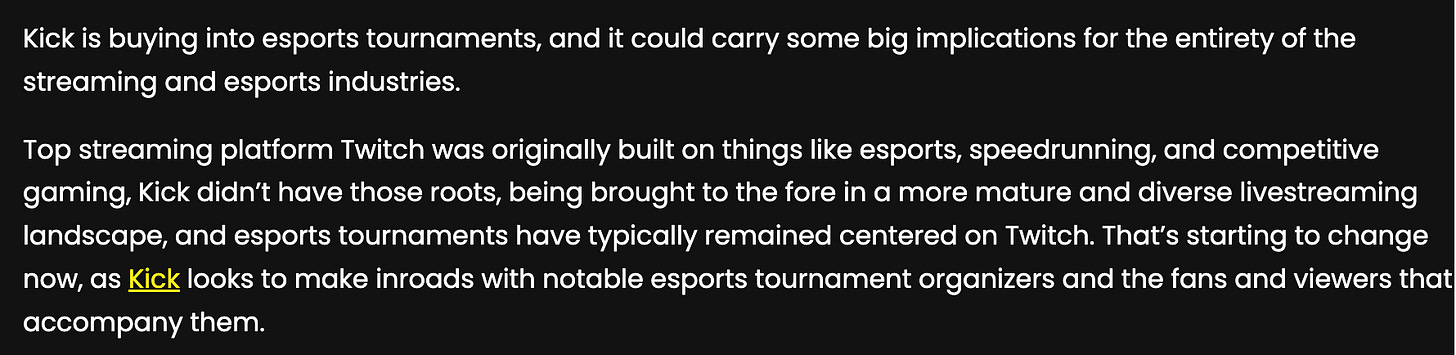

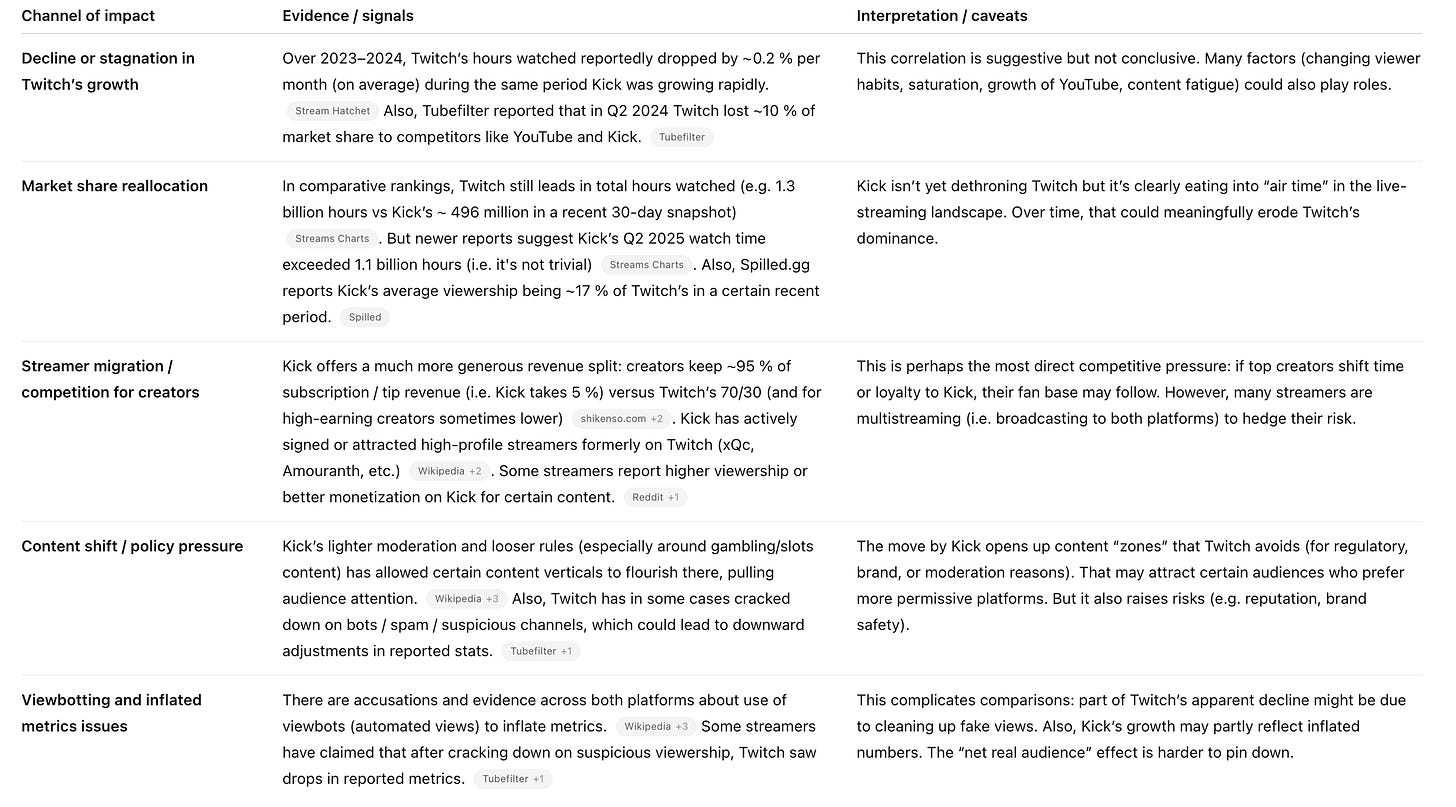

What’s remarkable is not just that Twitch’s share fell, but how fast it happened. Market share data from StreamCharts suggests that between 2022 and early 2025, Twitch’s global live-streaming share dropped from above 90 % to roughly 70–75 %.

For a category that seemed winner-take-most, that’s a structural shift.

That’s the point where the concept of a moat starts to invert. The very advantages that made Twitch powerful – network effects, creator dependence, brand inertia – became liabilities.

Creators were trapped just enough to resent it but not enough to stay forever. Once Kick offered them a credible exit, the migration began.

It reminds me of similar dynamics in other industries. Think of cable companies raising fees until streaming broke their hold, or payment processors that push take rates higher until fintech challengers arrive with cheaper rails.

Dominance blinds management to fragility. What looks like pricing power on a spreadsheet is often goodwill burning in disguise.

In the context of Twitch, the over-flex wasn’t catastrophic overnight, but it created the conditions for defection. By the time management realized that the moat relied on a delicate equilibrium between creator economics and platform profit, that equilibrium was already shifting. And the irony is that this wasn’t inevitable. Twitch could have continued compounding at lower margins for years, preserving goodwill and reinforcing its network density. Instead, it chose to optimize short-term economics – and in doing so, it weakened the foundation that made those economics possible.

That’s also why scale economies shared models are so powerful. Establishing this corporate DNA – and remaining true to it over time – is so damn hard!

Before we dive back in, a quick note…

Want to compound your knowledge – and your wealth? Compound with René is for investors who think in decades, not headlines. If you’ve found value here, subscribing is the best way to stay in the loop, sharpen your thinking, avoid costly mistakes, and build long-term success – and to show that this kind of long-term, no-hype investing content is valuable.

PS: Using the app on iOS? Apple doesn’t allow in-app subscriptions without a big fee. To keep things fair and pay a lower subscription price, I recommend just heading to the site in your browser (desktop or mobile) to subscribe.

Kick’s Counter-Strategy – Capital, Incentives, and Culture

If Twitch’s story is about managerial overreach, Kick’s is about calculated aggression.

The platform didn’t tiptoe into the market – it bulldozed its way in. Launched quietly in late 2022, Kick’s initial brand positioning seemed almost absurdly audacious: an upstart platform backed by the founders of Stake.com, a crypto-gambling site, offering streamers a 95/5 revenue split and near-total freedom of content. The proposition sounded unsustainable. But that was the point.

Kick’s founders understood two things: first, that Twitch had alienated many of its highest-value creators, and second, that live streaming’s economics can be subsidized by deep pockets for a surprisingly long time. Stake.com had billions in annual handle and a young, male, gaming-oriented audience – a perfect overlap with Twitch’s demographics. Kick didn’t need to be profitable; it just needed to look credible long enough to trigger defection.

And it worked. Within a few months of launch, Kick began poaching some of Twitch’s biggest stars. Contracts for xQc, Amouranth, and Adin Ross reportedly reached into the tens of millions of dollars.

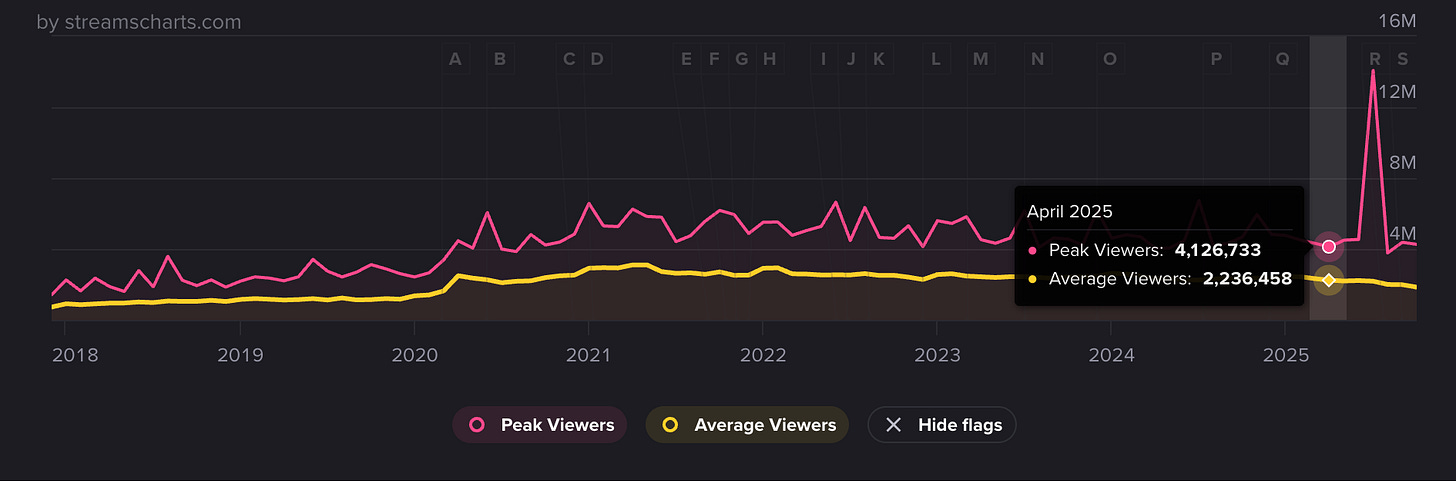

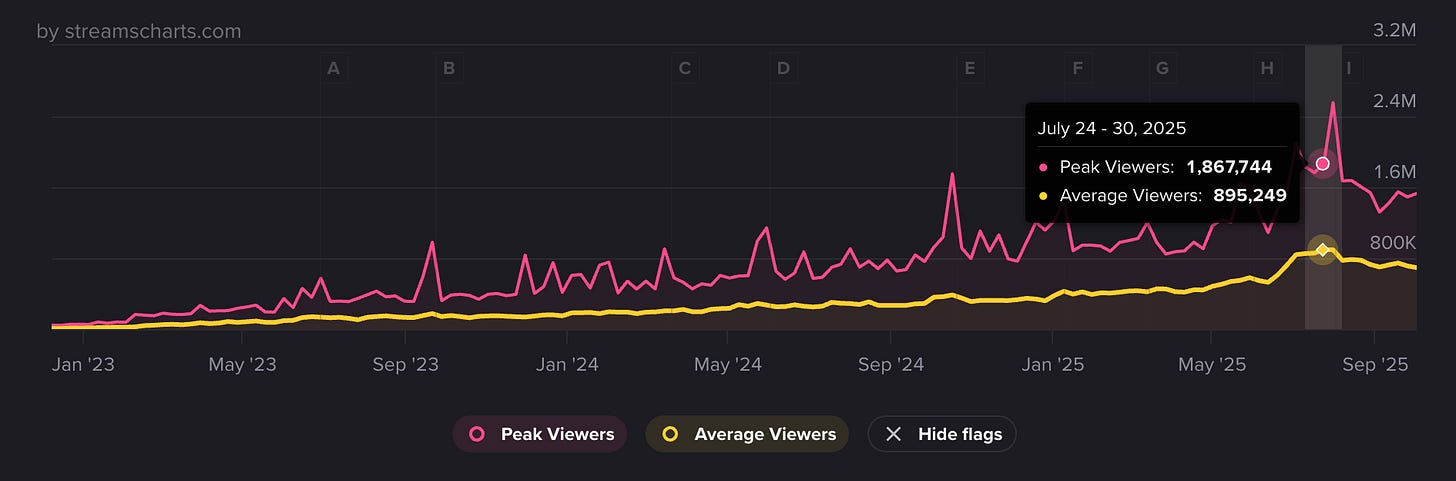

But beyond headline names, the broader story was quantitative. Kick’s total hours watched climbed from near zero in early 2023 to roughly 317 million in March 2025, an all-time record. Over the course of 2024, total watch time reached 2.1 billion hours, with an average concurrent viewership of about 258 thousand. That’s roughly double what the platform managed just a year earlier – a 142 % increase in viewership. And the numbers continued to trend higher.

At its peak in early 2025, Kick’s share of the global live-streaming market had crept past 20 %, while Twitch’s fell toward the 70–75 % range. In relative terms, that’s like a decade-old monopoly ceding a fifth of its domain to a company barely two years old.

Kick’s model worked because it turned Twitch’s biggest weaknesses – creator dissatisfaction and cultural rigidity – into its own strengths:

Where Twitch constrained monetization and moderation, Kick offered freedom.

Where Twitch cut creator splits to 50/50, Kick flaunted 95/5.

Where Twitch tightened sponsorship and gambling rules, Kick welcomed them.

To many streamers, it felt like the early, unfiltered version of Twitch all over again.

There’s also a psychological layer. Live streaming thrives on perceived authenticity. Twitch had become corporate; Kick felt chaotic but personal. It was imperfect, sometimes messy, but alive. Streamers who switched often spoke less about money and more about autonomy. They could design their own sponsorships, stream what they wanted, and interact with audiences without fear of demonetization. That sense of creative control can be just as powerful as economic incentives in shifting loyalty.

Behind the scenes, capital intensity played an enormous role. Live streaming isn’t cheap – bandwidth, CDN distribution, and moderation scale linearly with user growth. But Kick’s backers could absorb the burn. The gambling ecosystem funding it meant that Kick could treat streaming not as an isolated business but as a brand-building investment. In effect, it was marketing spend disguised as a platform. That’s why, even as analysts questioned its sustainability, Kick doubled down on infrastructure, international expansion, and partnerships with esports tournaments.

By early 2025, Kick’s reach had expanded dramatically across Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia – regions where Twitch’s growth had stalled. Non-English-language categories accounted for a rising share of total hours watched, mirroring the globalization pattern that once propelled YouTube.

Now, skeptics will point out that not all of Kick’s growth is “clean.” Reports from analytics firms like StreamCharts and StreamHatchet have flagged inflated metrics and suspected viewbotting. And multistreaming complicates attribution: many creators broadcast simultaneously on both platforms, splitting rather than transferring their audiences. But even accounting for inflated figures, the directional trend is clear. Kick is not just surviving – it’s reshaping the competitive equilibrium of an industry once thought winner-take-all.

That alone reveals something important about moats. A structural moat should, by definition, resist capital-driven assaults. You can pour billions into search and still fail to dent Google. You can spend endlessly on smartphones and still not dethrone iOS. In those cases, money doesn’t buy relevance because the moat is underpinned by user habit, ecosystem lock-in, and product quality.

From an investing standpoint, Kick’s rise is a fascinating anomaly. It’s rare to see a category leader lose this much share this fast outside of regulatory shocks or technological discontinuities.

There was no paradigm shift here – no AI revolution, no new hardware interface. Just capital and culture exploiting managerial complacency. That, to me, makes Twitch’s decline one of the purest examples of what happens when network effects are mismanaged rather than lost.

Investor Takeaways – Managing Moats vs. Milking Them

As investors, we often look for companies with moats so strong that competition feels futile. We prize pricing power, network effects, and customer lock-in because they give businesses the ability to earn high returns on capital for long periods. But what the Twitch case reminds me of is that how a company uses its moat matters as much as the moat itself.

Twitch’s management team had every reason to believe they could flex their power. They had a near-monopoly, a loyal user base, and creator inertia built into their network effects. But they confused the existence of a moat with the permission to exploit it.

Pricing power doesn’t mean you should raise prices. Switching costs don’t mean your partners won’t explore alternatives. And brand equity doesn’t mean goodwill is infinite.

When I think about the companies that do manage their structural advantages well, they tend to share one common trait: (some degree of ) restraint.

What I take away from this episode is a simple but powerful idea: a moat protects you only as long as you protect it back. The moment a company starts viewing its moat as something to harvest rather than cultivate, the advantage begins to decay. Twitch had gravity on its side for years. Then it turned that gravity into a tax. And gravity, once reversed, is hard to stop.

Fascinating