Every year, I write two letters (one year-end and one half-year letter) to my parents whose portfolio I started overseeing in mid-2025. I will share parts of the letters I write to them here on the blog, too.

Every year when I write this letter, I want to begin in the same place: Appreciation. For the trust you’ve placed in me to manage some of your capital. Your willingness to let me run the process independently means a lot. Thank you for backing the work, the thinking, and the patience that good investing requires.

As you know, I approach each semi-annual update with the same objective: if you read it closely, you should walk away with one idea that improves how you think about business, investing, risk, or company valuation.

This year, I picked two concepts to share. One is probably more intuitive to grasp. The other one is certainly more nuanced, maybe more “advanced.” I’m happy to discuss the concepts further in person. And anyway, you don’t need to memorize either. Just enjoy the intellectual stimulation of thinking this through along with me.

Concept 1: Outcomes follow a power law distribution & practical implications

I recently wrote a blog post about investor Henry Ellenbogen’s appearance on an investing podcast. In this piece, I also wrote about Ellenbogen’s archival work early in his career at the New Horizons Fund, which revealed some fascinating data points: Over rolling 10-year windows, only around 1% of companies – about 40 out of 4,000 – compound at 20% annually or better, crossing the 6x return threshold. These are the extreme right-tail outcomes, the “valedictorians” as he called them. And crucially, nearly 80% of them began their journey as small caps (companies with a relatively small market capitalization, often defined as between $250 million and $2 billion. Nobody recognized them as future “titans” when they were small – think Walmart at store #50 or a tech company product iteration #3 (Ellenbogen might have had Duolingo in mind; which I know you are a heavy user of yourself). They became them (i.e. business titans) later, though. Slowly and steadily. One store after another. One product iteration after another. Winning one customer at a time.

Ellenbogen used Walmart as a prime example of these 1% long-term winners. He shared that had Walmart not been sold early by the fund, it would have mathematically outweighed the sum of everything else the fund managed. Everything else. Think about that! The lesson here is not about Walmart specifically, though. It is rather a lesson about letting your winners run. A lesson about non-interruption. The cost of trimming a real outlier is not visible at the moment you trim it. The bill arrives years later, compounding against you in silence.

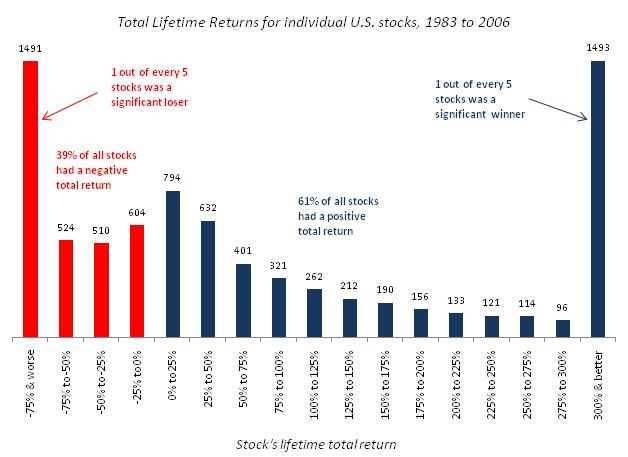

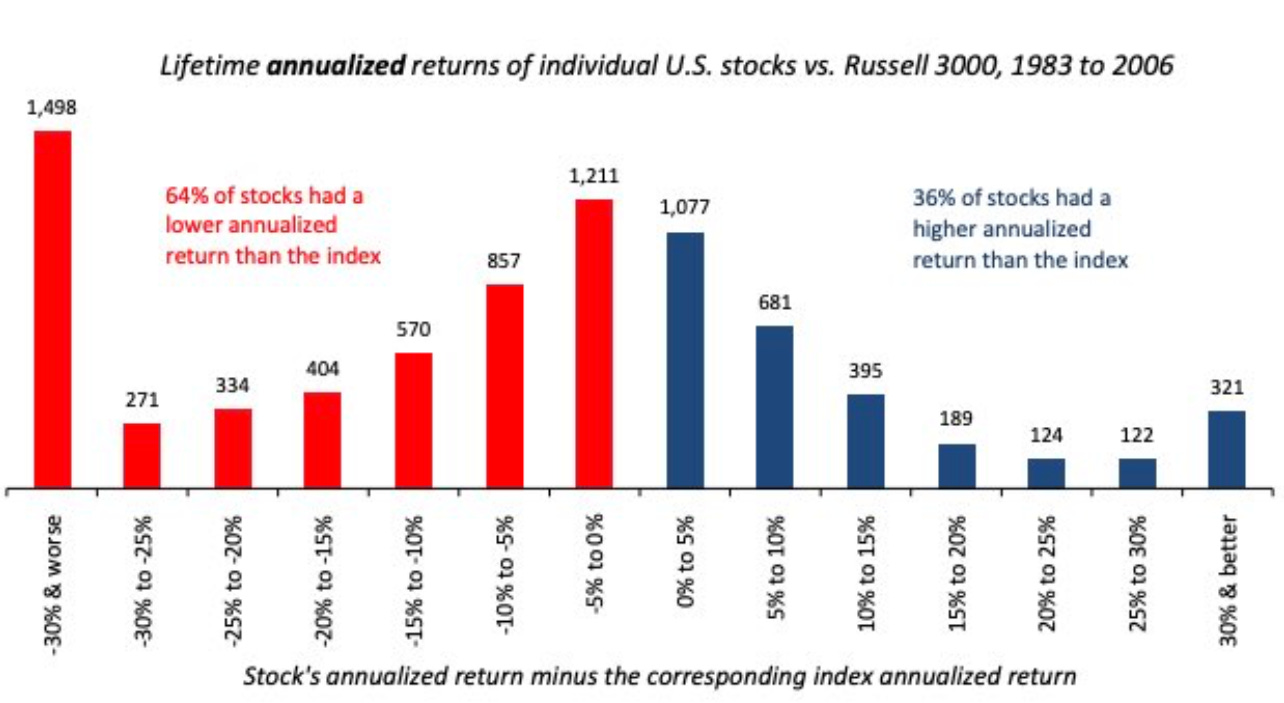

When preparing this letter, and thinking more about this subject, I came back to Meb Faber’s 2008 broader market study titled “The Capitalism Distribution: Fat Tails in Action,” which supports the same geometry: over 23 years of U.S. public market data, 39% of stocks delivered negative lifetime returns, 64% underperformed the Russell 3000, 18.5% lost 75% or more, and 25% of all stocks created essentially all net wealth. Even most winners didn’t stay (public) winners forever – 60% of the companies vanished due to acquisitions.

Broadly speaking, the figures support Ellenbogen’s point. So if generally speaking, only 1% of companies increase multi-fold (call it 6x or more) over a decade, the question to ask is:

“How do I increase the odds of holding the 1% long enough without getting bored, scared, or clever at the wrong time?”

That’s where the idea of a so-called “coffee can portfolio” comes in. This concept was first developed by Robert G. Kirby in a paper titled “The Coffee Can Portfolio” in 1984. Kirby, too, recognized that usually investors’ few best-performing investments will represent the vast majority of their returns. As a rule of thumb – maybe that’s easier to memorize –, you can think of it as an 80/20 rule: 20% of your investments are likely to produce 80% of your returns. Based on this observation, Kirby argued that “you can make more money being passively active than actively passive. “

The active part of this strategy is to make investment decisions.

The passive part is your behavior - being able to do nothing, not to sell at all, for as long as you possibly can. Investors should simply be sitting on their hands.

Kirby uses the image of a coffee can to illustrate this “passively active” approach. According to him, the name “coffee can portfolio” goes back to the American Old West:

“The Coffee Can portfolio concept harkens back to the Old West, when people put their valuable possessions in a coffee can and kept it under the mattress. That coffee can involved no transaction costs, administrative costs, or any other costs. The success of the program depended entirely on the wisdom and foresight used to select the objects to be placed in the coffee can to begin with.“

The portfolio structure Kirby proposed was not aiming to predict which company would become the 6x winner. It was rather trying to eliminate the decision that “destroys” the future 6x winner once you find it.

Once you accept that outcomes are skewed, your role as an allocator changes. Your job is no longer to constantly optimize. It becomes protecting. Against impatience. Against randomness. Against your emotions. Against information triggers that sound meaningful in the moment but turn out immaterial to the longer-term trajectory. The biggest long-term risk in any portfolio is adopting a mindset that expects linearity from a system that is mathematically non-linear.

The concept should shape future decisions in two ways:

Expect skew, not symmetry. Outcomes will be uneven. Normal. The portfolio will likely concentrate in a few select winners. Normal.

Non-interruption is a strategy. We attempt to do very little by choice. Compounding is fragile if you intervene arbitrarily. As the famous Charlie Munger said, "The first rule of compounding is to never interrupt it unnecessarily."

Concept 2: Why the Best Economics Rarely Look Best at First

Generally speaking, I’m drawn to companies that look “unfinished” in their financials while “finishing” something structurally important – a "structural” differentiator protecting future economics – in the background. When a proven core business deliberately funds a younger, more ambitious business, the financial statements look suboptimal. Reported margins may look weak. The business may even be unprofitable. The path towards profitability stretches as management constantly finds new opportunities to deploy capital into – hopefully at attractive rates of course. Setbacks happen, too. The market reaction is often predictable: frustration, impatience, “short-termism,” disappointment, depressed valuation multiples.

But this is a set-up investors should actively look for in my view. It’s a feature of long-term compounders to be understood. And it’s one of my most favorite hunting grounds.

Fred Liu, managing partner at Hayden Capital, recently described it well in a tweet on X – I like the “baby business” framing:

“Since the mature biz throws off cash flow, building the baby biz is non-dilutive to investors – except just lower profits / margins, while the company reinvests. But the public markets hate these set-ups… So you get a free call option, with downside protection from the mature biz.”

His examples – Sea Ltd (Garena funding Shopee), Afterpay (Australia funding the U.S.), AppLovin’s gaming studios masking the rise of its adtech network – all share the same anatomy: the economics were attractive long before text accounting metrics made them look “real.”

That structure is why I like these businesses. You get a working foundation, misunderstood capital intensity, and optionality on a moat still being cemented, often being expanded by stacking new layers on top of already existing competitive advantage layers. I think of them as emerging-moat compounders, or CAP-builders (CAP stands for competitive advantage period; the time during which a company can earn excess returns on reinvestments): firms that intentionally sacrifice near-term profits to expand how long the business can generate high incremental returns. If the company is run by capable managers, the investments are not random. They tend to aim at scale advantages, denser networks, regulatory alignment, or improving unit economics. The payoff only becomes legible later, once reinvestment intensity eases or scale thresholds are crossed. Sometimes both.

Here’s the twist most investors miss. The highest economic returns are often earned when reported returns look rather poor. Companies in heavy build mode can generate extraordinary incremental returns on the capital they deploy, even while GAAP or IFRS accounting refuses to highlight it. They earn high ROIIC when unadjusted textbook ROIC figures are still deeply negative. And when textbook ROIC finally screens as “excellent,” the business has often already passed its most lucrative phase of incremental capital efficiency – and reinvestment opportunities at these returns dry out.

Great returns can be enjoyed when you identify positive inflection points before the market does. And inflection points don’t wait for accounting. The math peaks early, then slopes.

This creates a second decision lens for the future: if you only buy companies once margins are clean and ROIC tables look polished, you are buying after significant increases in intrinsic value already happened. Those tend to be good businesses, relatively stable ones. The downside risk is arguably smaller. But they also tend to be businesses no longer growing their intrinsic value at a rate I find satisfying. And they most certainly won’t be part of the “1% cohort” we discussed above in the segment on concept 1. And if you sell companies because reinvestment temporarily depresses reported margins, you may be selling the very “1%-winners” before the story could fully unfold.

How this impacts decisions going forward:

A company can be operationally messy, financially messy, optically messy – and economically magnificent (if you can zoom out beyond a quarter). Early. Before the textbook numbers agree.

The moment a business looks obvious on a trailing ROIC basis, incremental returns on new invested capital may already be normalizing. Maybe reverting.

The biggest portfolio mistakes are rarely analytical mistakes. Timing mistakes. Interruption mistakes (see concept 1).

The job of the long-term allocator is to recognize inflection points before consensus.

Business Updates

Investors are conditioned to track price charts the way sports fans track league tables. And it’s somewhat understandable. Prices are always available, constantly updated, emotionally charged, and maybe also convenient. But as we were trying to stress in our inaugural letter, shares in companies are not abstract tokens that wiggle on a screen. They are ownership claims on real businesses. Thus, what ultimately determines long-term outcomes is not the daily verdict of the market, but the actual development of the underlying companies (and the price relative to the real value of the business that you bought your stake at) – their competitive position, growth vectors, unit economics, capital allocation, etc. If you want to judge intrinsic value progress, judge the business, not the stock.

Based on this understanding, in the paragraphs below, I’ll share brief updates on a few select holdings, focusing on some recent events and developments that carry real consequences for the businesses’ future.

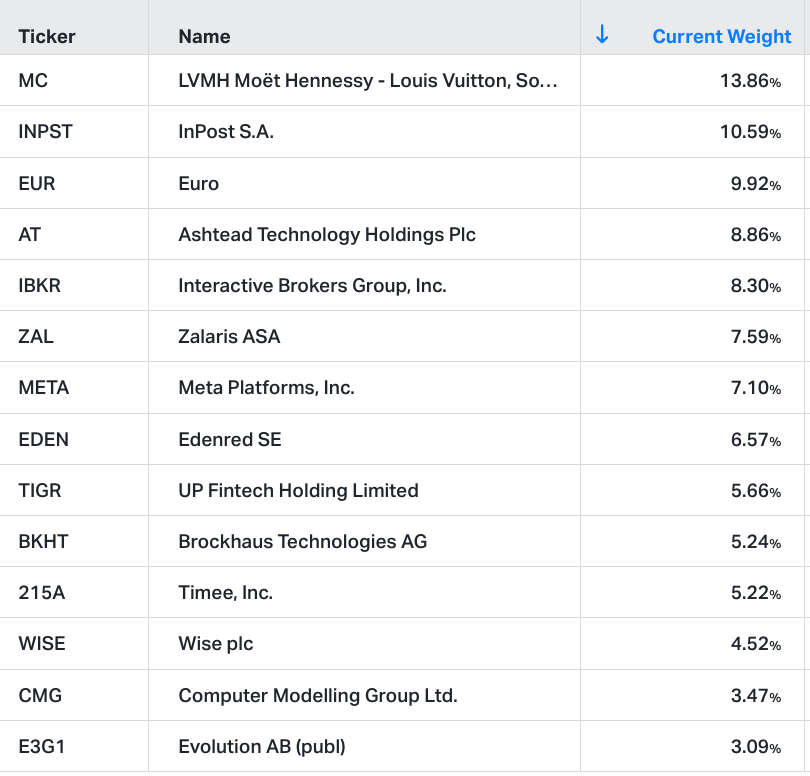

Before we start, the current portfolio composition looks like this:

InPost is a new position in the portfolio, and we discussed what the business does privately (it’s the leading out-of-home legostics platform in Europe). InPost is a great case study for the second theoretical concept outlined above: a mature domestic engine (InPost’s Polish business) funds a moat that is still expanding internationally (across a wide range of European countries, with the UK and France representing the two biggest markets). The core business in Poland continues to generate significant cash flow at attractive margins and is financing the network build-out across Europe. This inevitably depresses reported margins, because the investment is front-loaded while the benefits are back-loaded.

Moving on to recent developmens, one such development includes the decision by management to progress with the Yodel integration – a 2025 a £106m acquisition – deliberately rather than hastily, postponing certain integration steps during the Christmas season that management initially wanted to take sooner to avoid operational friction that could compromise customer delight. We think this – focusing on providing customers the best possible consumer experience – was the right one to make. Speaking of InPost’s UK business, CEO Rafal Brzoska recently backed the UK thesis with accelerating adoption metrics: 44% of UK consumers now plan to use parcel machines this holiday season, up from 34% only three months ago. Shipments handled through machines grew from 26% to 36%, return rates climbed from 23% to 39%, and over half of 18–34-year-olds are already active users. These numbers are thesis-confirming because they demonstrate broad behavioral change, which is arguably rather difficult to pull off and normally takes time (many years). Third, the company also secured an important UK High Court ruling confirming the warrant documents of Yodel’s former owner were not genuine, removing a governance overhang and enabling Yodel to continue its restructuring path in 2026 under InPost’s ownership. Beyond that, InPost announced a new eBay partnership, embedding locker-based parcel flows directly into the eBay marketplace for the first time, unlocking optionality for both buyers and sellers. Finally, I came across another insightful data set that highlights how dominant the service perception already is: across pickup convenience, app usability, parcel condition, delivery speed, and tracking reliability, InPost’s Poland business leads every single peer category measured.

Up Fintech Holding operates in a structurally attractive industry, grows incredibly fast (faster than many competitors), and is run by a founder who pursues an ambitious long-term vision. Up Fintech Holding delivered Q3 results that reinforced the thesis that account growth, asset growth, and product expansion are compounding in parallel. The company posted a 27% revenue CAGR over the past three years and grew revenue 73% YoY last quarter alone, with net profit expanding 180% and client assets increasing 49%. The client acquisition strategy already hit the full-year guidance of 150,000 newly funded accounts by the end of Q3, and management implied continued strong funded account additions in Q4 (at least 18,000 incremental accounts beyond Q3’s closing figures). What matters more than the headline growth figures though is the composition of that growth and the increasing account quality: 40% of new funded users now come from Singapore, 35% from Hong Kong, 20% from Australia and New Zealand, only 5% from the U.S. Hong Kong has emerged as a second core growth engine alongside Singapore, contributing over 30% of new funded accounts for the first time, while maintaining consecutive quarter averages of USD 30,000 net inflow per new client and a new Singapore average exceeding USD 60,000 (for comparison, Robinhood's average account size is significantly smaller; somewhere in the range of USD 10,000). Importantly, onshore retail users now represent less than 15% of total client assets, marking a meaningful mix shift toward internationally positioned, higher-quality investors. While the company already produces impressive 27% net income margins, Hong Kong – the region with the highest average net inflows – still contributes disproportionately little to group profit, because management is prioritizing density of products, switching costs, and market share before profit contribution. That means there is likely significant operating leverage left, especially when compared to competitor Futu Holding’s nearly twice as high margins. The company self-clears core products, owns the clearing stack, and is already profitable in Tiger Brokers Hong Kong, even while intentionally reinvesting into product breadth rather than bottom-line optics. Macro fears around tariffs or trade tensions have no real consequence for the business itself, but they do have consequence for investor sentiment: sentiment often misprices companies like this when narratives overshadow incentives.

When you manage capital for the long run, trust in management teams is usually a cornerstone. Lose that trust, and the cleanest rule is often to exit. Brockhaus Technologies has been a tricky case for me this year because the investment sits at the intersection of a trust impairment and a major valuation gap. The material difference between share price and intrinsic value has kept the position alive, even while the narrative, and also tangible developments on the business level, would have made it an easy sell months ago. Now, on December 23, Brockhaus announced the sale of all of its shares in BLS Beteiligungs GmbH (“Bikeleasing”), which it held indirectly via BCM Erste Beteiligungs GmbH, to Decathlon Pulse SAS, part of the French Decathlon Group. The purchase agreement values Bikeleasing at an enterprise value of €525 million. Based on the consolidated figures as of September 30, 2025, the illustrative pro-rata value attributable to Brockhaus’ stake is approximately €240 million. For much of this year – and also prior to the deal announcement – Brockhaus shares traded around €10 per share, implying a market cap of roughly €100 million. On the announcement day, the stock increased by more than 50%, which makes sense if you adjust for cash and debt and translate the deal value into per-share terms. Depending on the adjustments, the transaction alone likely represents around €22–23 per share in value. Brockhaus also owns IHSE, which should reasonably carry a stand-alone value of around €40–50 million. But even after the 50%+ move, the stock still only traded below €16 per share. Why? A few thoughts:

It is not fully clear whether the deal will be paid entirely in cash or if other instruments or delayed payments are part of the structure. This ambiguity around composition may make market participants cautious.

There is also a bargaining position problem once a seller is perceived as having to reinvest the proceeds under time pressure, similar to situations in sports where a team must replace a key player and every counterparty knows the budget and the time constraint. Imagine Bayern Munich selling Harry Kane for 80€ million tomorrow. Bayern Munich would need a replacement before the end of the winter break; they are acting under time constraints and everyone knows they have €80 million+ at hand. This puts the team in a bad bargaining position. The market may be anticipating the same regarding Brockhaus.

On top of this, Brockhaus’ acquisition track record has been mixed.

Finally, if Brockhaus distributed the proceeds directly to shareholders, the share price would likely reprice higher, but this appears unlikely, because direct distribution would remove management from future incentives, compensation, and control.

In sum, the market is (somewhat rightfully) discounting the proceeds because it assumes redeployment risk remains. I’ll be continuing to track the situation closely.

Wise’s share price has declined about 23% since September. The business itself continues to execute on its long-term mission with consistency, focusing on product improvements, geographic expansion, and customer economics rather than short-term margin improvements. The key metrics to track are all pointing in the right direction:

Active customers 13.4m (+18%)

Total cross-border volumes £85bn (+24%)

Spend on Wise cards £28bn (+27%)

Customer holdings £25bn (+37%)

Own cash on the balance sheet £1.6bn (+49%)

Wise Platform volumes £4.2bn (+55%)

The recent debate around stablecoins disrupting Wise’s model is – in my view – overblown because it lacks a nuanced assessment of true cost advantages, adoption timelines, and real-world switching costs. The regulatory environment, compliance requirements, and consumer behavior suggest that adoption will be uneven, gradual, and unlikely to compress Wise’s core value proposition in the short to medium term. Market narratives around disruption tend to front-run reality, especially when the disruption itself is still searching for mainstream workflows (the majority of stablecoin transactions today are still primarily driven by crypto trading activity, rather than being used in broader financial or commercial contexts).

Next, let’s discuss our investment in Edenred, which is down 24% since our purchase. Edenred has been affected by regulatory headwinds. However, regulation is one of those areas where markets often extrapolate the worst-case instantly and indefinitely, without adopting a probabilistic multi-scenario approach. On top of this, in Edenred’s case, the market is also not adjusting for the parts of the business that aren’t exposed to the same regulatory risk. Edenred has been punished heavily on price – down about 63% over the past three years – even while the business delivered real operating progress, growing operating income roughly 40% at stable EBIT margins of around 31%. The result is a rather dramatic re-rating of the company’s EV/EBIT multiple, from around 24x to roughly 8x. Edenred’s regulatory environment in Brazil has clearly tightened after policy changes on the worker food program (PAT), creating material headwinds for the regulated part of the business in Brazil (and the business is experiencing similar headwinds in a few European countries too). But of course, Edenred is operating globally, and maybe more importantly, another critical detail is often ignored: around 60% of Edenred’s revenue comes from unregulated activities (activities not dependent on government-subsidized programs). The regulated business carries risk, but it still carries value. It is not worthless. The law published recently includes a 3.6% cap on merchant fees (effective immediately), a 15-day redemption period (7 days for smaller transactions), mandatory interoperability effective one year from publication, and fee-free portability for employers with more than 500 employees upon written request. The positive consequence of lower share prices is that every euro spent on buybacks now retires shares at a fraction of the price only a few years ago, creating shareholder value through the simple mechanism of reducing the share count at what I believe is too-cheap of a valuation. Edenred’s core economics are still working, regulatory impacts are meaningful but partial, and the company’s ability to repurchase shares at single-digit earnings multiples is now maybe the most asymmetric consequence.

Other holdings deserve only brief updates:

Zalaris remains a high-conviction investment for me. Rumors about a potential acquisition target resurface occasionally, but I hope the company will remain independent and compound for years to come. The market opportunity is large enough to support many years of solid intrinsic value growth.

LVMH is slowly seeing light at the end of the tunnel and could return to higher growth in the quarters ahead. In its last quarter, LVMH was growing across all segments, stopping the multi-quarter revenue declines that started in H2 2023 (and caused the poor stock performance since).

Timee is a new investment. It is a marketplace platform in Japan that connects businesses with flexible hourly workers, handling scheduling, compliance, and staffing workflows. I recently listened to a podcast with the founder, who is the youngest CEO of all CEOs in the portfolio companies, at just 28 years. He strikes me as very ambitious (planning to expand into other industries and internationally), and hopefully, he will continue to compound our capital as the CEO for decades to come (the opportunity in Japan is in my view large enough to justify the current share price). I hope we stick to the coffee can approach here; this will be the toughest challenge).

Evolution Gaming continues to struggle, but the stock looks very cheap to me, and the shareholder yield of almost 10% (a comprehensive measure of how much cash a company returns to its investors, going beyond just dividends to include net share buybacks) pays us while we wait for a re-rating.

Computer Modelling Group and Ashtead Technology trade at what I believe are very attractive prices, and I expect long-term returns to be very satisfying, especially once the oil cycle turns. The sector is ignored and unloved. Temporarily. Both companies aren’t pure commodity producers but rather specialized service, equipment, and/or technology providers. Let me remind you of each company’s business and how they are important during various parts of the cycle:

Computer Modelling Group operates at the intersection of software and subsurface engineering. When new project sanctioning slows, operators rely more heavily on simulation tools to optimize existing fields. They run enhanced recovery scenarios, model tie-backs, test drilling patterns, evaluate reservoir risk, and push for higher productivity per well. When the cycle turns upward again, and new exploration programs begin, demand for these tools rises even further. The result is a dual-cycle business: one that benefits (or at least the impact is cushioned due to the mission-critical nature of the offering) from the downcycle’s need for efficiency and the upcycle’s need for development.

Ashtead Technology sits in a different but equally interesting niche. Their equipment and rental solutions power subsea inspections, survey work, and offshore maintenance. When producers delay megaprojects, they still need to maintain what they already have. Offshore wells don’t stop aging just because capex budgets shrink. And when oil prices eventually rise and offshore activity accelerates, demand ramps.

If the thesis plays out, both companies find themselves pulled upward by increased activity. If the thesis takes longer, they keep earning money anyway. And if the thesis is wrong altogether, they still have defensible business models and structural advantages that give them a chance to compound value somewhat independent of the commodity price.

Interactive Brokers and Meta are high-quality long-term compounders, and while we observe Meta's AI capital allocation spent somewhat critically, in the spirit of the Coffee Can, we're not going to sell our stake in a world-class business that we bought below $500/share during the Liberation Day selloff in April. IBKR is simply one of the best businesses in the world with a long runway. It’s not optically cheap anymore (up 70% since our purchase), but I believe the business will grow into its current valuation over time.

Concluding Thoughts

The businesses you own stakes in today are laying foundations at different stages of maturity, and the best future outcomes will come from letting the right ones run their course while sizing them in ways that make patience sustainable. Thank you again for trusting me with this process. The work continues, the puzzle continues, and the real returns will continue to be earned not in the quarterly headline results, but in the incremental improvements that are stacked on top of each other quarter after quarter over multi-year timeframes.

René

Very interesting. Thank you. I have a lot of stocks to look at here!

Great job, as always.